Sensitivity and Specificity in DNA Methylation Detection: A 2025 Guide for Biomarker Validation and Clinical Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of DNA methylation detection methods.

Sensitivity and Specificity in DNA Methylation Detection: A 2025 Guide for Biomarker Validation and Clinical Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on evaluating the sensitivity and specificity of DNA methylation detection methods. It covers foundational statistical concepts, performance characteristics of current technologies (including bisulfite sequencing, microarrays, EM-seq, and third-generation sequencing), strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing assays in real-world scenarios, and frameworks for rigorous validation and comparative analysis. With a focus on clinical application, the review also explores the growing role of machine learning in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and the pathway for translating methylation biomarkers into clinically viable tools for cancer diagnosis and monitoring.

Core Principles: Defining Sensitivity and Specificity in Epigenetic Analysis

In medical research and clinical practice, the evaluation of any diagnostic test relies on fundamental statistical metrics that determine its ability to correctly identify subjects with and without the target condition. Diagnostic accuracy provides the foundational framework for understanding test performance, guiding clinical decision-making, and advancing diagnostic technologies. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, mastery of these metrics is essential for developing, validating, and implementing new diagnostic tools, particularly in emerging fields like molecular diagnostics and epigenetic testing.

The core metrics of sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) each provide distinct yet complementary information about test performance. These metrics are derived from a 2x2 contingency table that cross-references test results with true disease status, as determined by a reference standard. Understanding their individual definitions, calculations, interrelationships, and applications is crucial for accurately interpreting test results and assessing their clinical utility. This foundation becomes especially important when evaluating innovative detection methods, such as DNA methylation markers for cancer screening, where test performance must be rigorously characterized before clinical implementation.

Core Definitions and Clinical Interpretations

Foundational Metrics

The following table summarizes the four core diagnostic accuracy metrics, their definitions, and key clinical implications:

| Metric | Definition | Clinical Interpretation | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | Proportion of people with the disease who test positive [1] [2]. | A test's ability to correctly identify individuals who have the condition. A highly sensitive test is good at "ruling out" the disease when negative (SN-Out) [1]. | Independent of disease prevalence [1]. |

| Specificity | Proportion of people without the disease who test negative [1] [2]. | A test's ability to correctly identify individuals who do not have the condition. A highly specific test is good at "ruling in" the disease when positive (SP-In) [1]. | Independent of disease prevalence [1]. |

| Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Proportion of people with a positive test who actually have the disease [1] [2]. | The probability that a patient with a positive test result truly has the disease. | Heavily influenced by disease prevalence [1] [3]. |

| Negative Predictive Value (NPV) | Proportion of people with a negative test who truly do not have the disease [1] [2]. | The probability that a patient with a negative test result is truly free of the disease. | Heavily influenced by disease prevalence [1] [3]. |

Statistical Formulas and the 2x2 Table

These metrics are calculated from a 2x2 contingency table that compares the test results against a reference standard. The standard table structure is visualized below, which forms the logical basis for all calculations.

The formulas derived from this table are fundamental for quantifying test performance [4] [2]:

- Sensitivity = True Positives (A) / [True Positives (A) + False Negatives (C)]

- Specificity = True Negatives (D) / [True Negatives (D) + False Positives (B)]

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV) = True Positives (A) / [True Positives (A) + False Positives (B)]

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV) = True Negatives (D) / [True Negatives (D) + False Negatives (C)]

Application in Methylation Detection Methods Research

DNA methylation analysis has emerged as a powerful tool for cancer detection and risk stratification. The performance of these epigenetic tests is evaluated using the standard diagnostic accuracy metrics, providing a clear framework for comparing different biomarker panels and methodologies.

Performance of Methylation Markers in Cervical Cancer Screening

Research has validated several DNA methylation markers as triage tests in high-risk human papillomavirus (hrHPV) positive populations for detecting cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 or worse (CIN2+). The following table summarizes published performance data for different methylation panels, illustrating the trade-offs between sensitivity and specificity.

| Methylation Marker Panel | Target Condition | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C13orf18/EPB41L3/JAM3 | CIN2+ | 80% | 66% | 40% | 91% | [5] |

| SOX1/ZSCAN1 | CIN2+ | 63% | 84% | 40% | 93% | [5] |

| FAM19A4/miR124-2 | CIN2+ (vs. Positive Histology) | 50% | 87% | N/R | N/R | [6] |

| EPB41L3/JAM3 | CIN2+ | 68.7% | 96.7% | N/R | N/R | [7] |

N/R: Not explicitly reported in the cited study.

The data demonstrates that different marker panels offer varying diagnostic trade-offs. For instance, the C13orf18/EPB41L3/JAM3 panel offers higher sensitivity (80%) but lower specificity (66%), whereas the SOX1/ZSCAN1 panel offers lower sensitivity (63%) but higher specificity (84%) for detecting CIN2+ [5]. This inverse relationship between sensitivity and specificity is a common phenomenon in diagnostic testing. The high specificity of the EPB41L3/JAM3 panel (96.7%) makes it a promising triage tool to reduce unnecessary referrals and overtreatment in screening programs [7].

Impact of Disease Prevalence on Predictive Values

A critical concept in applying these metrics is that while sensitivity and specificity are considered intrinsic properties of a test, PPV and NPV are highly dependent on disease prevalence in the population being tested [1] [3]. This relationship has major implications for how a test performs across different clinical settings.

The following table illustrates how PPV and NPV change with prevalence for a hypothetical test with 90% sensitivity and 90% specificity:

| Prevalence | Positive Predictive Value (PPV) | Negative Predictive Value (NPV) |

|---|---|---|

| 1% | 8% | >99% |

| 10% | 50% | 99% |

| 20% | 69% | 97% |

| 50% | 90% | 90% |

Adapted from data illustrating the relationship between prevalence and predictive values [1].

As prevalence decreases, PPV decreases because there are more false positives for every true positive, a scenario described as "hunting for a needle in a haystack" [1]. Conversely, NPV increases as prevalence decreases because a negative result is more likely to be a true negative. This explains why a screening test used in a general, low-prevalence population may have a disappointingly low PPV, despite having high sensitivity and specificity. This principle is vividly demonstrated in real-world screening; for example, low-dose CT scans for lung cancer have high sensitivity (93.8%) and specificity (73.4%), but in a high-risk population with a cancer prevalence of 1.1%, the PPV was only 3.8%, meaning most positive results were false positives [3].

Experimental Protocols for Methylation Marker Validation

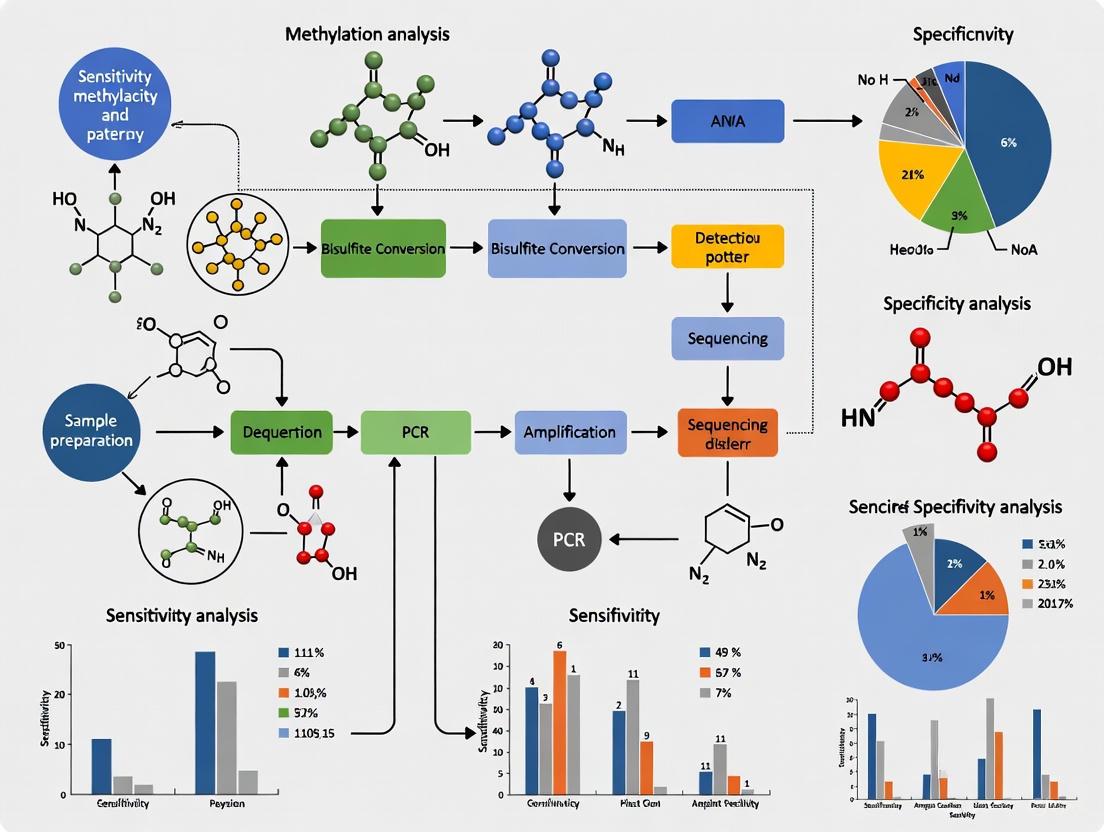

The validation of DNA methylation markers for clinical application involves a multi-step process to ensure robustness, reproducibility, and clinical utility. The workflow for such a study, from sample collection to data analysis, is outlined below.

Detailed Methodological Components

Population Selection and Sample Collection: Studies are typically conducted within a defined screening population. For example, a validation study for cervical dysplasia detection collected liquid-based cytology samples from patients before conization or hysterectomy, with subsequent histological confirmation serving as the reference standard [7]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria (e.g., age, HIV status, history of immunosuppression) must be clearly defined.

DNA Isolation and Bisulfite Treatment: DNA is isolated from cytology samples, often using phenol:chloroform:isoamylalcohol extraction and precipitation [5] or commercial kits like the QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [6]. A critical step is sodium bisulfite conversion, which deaminates unmethylated cytosine residues to uracil, while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged. This allows for the subsequent differentiation of methylated and unmethylated DNA sequences via PCR-based methods [5] [6]. The PreCursor-M+ kit protocol, for instance, uses bisulfite-converted DNA as its starting material [6].

Quantitative Methylation Analysis: The most common analytical method is quantitative Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP). This technique uses primers and probes designed to specifically amplify either the methylated (converted) or unmethylated (unconverted) DNA sequence. The relative level of methylation is determined by comparing the quantity of the target amplicon to a reference gene (e.g., ACTB) to control for DNA input, often reported as a ΔCt value [5] [7]. A sample is classified as methylation-positive if its ΔCt value is below a pre-defined cutoff established in training sets [7].

Validation and Statistical Analysis: Test performance is evaluated by comparing methylation results against the reference standard diagnosis (e.g., CIN2+ confirmed by histology [7]). Sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV are calculated using the standard formulas. The diagnostic accuracy of methylation testing is often directly compared to established methods, such as hrHPV testing, to assess its potential value as a primary screening or triage tool [6] [7].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents, kits, and instruments essential for conducting DNA methylation analysis research, as cited in the literature.

| Item Name/Type | Specific Function in Methylation Analysis | Example Product/Model |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kit | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA from clinical samples (e.g., cervical scrapings, liquid-based cytology). | QIAamp DNA Mini Kit [6] |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemical treatment of DNA that converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils, enabling methylation status discrimination. | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research) [5] [6] |

| Quantitative PCR System | Platform for performing real-time PCR to amplify and detect methylated DNA sequences with high sensitivity. | ABI 7300/7500 Real-Time PCR System [7] |

| Methylation-Specific Detection Kit | Contains optimized primers and probes for targeted amplification of specific methylated genes. | PreCursor-M+ Kit (for FAM19A4/miR124-2) [6]; Methylated Human EPB43/JAM3 Gene Detection Kit [7] |

| DNA Quantitation Assay | Accurate measurement of DNA concentration prior to bisulfite conversion and PCR to ensure standardized input. | Qubit dsDNA BR Assay Kit [6] |

| Reference Standard Assay | Provides the definitive diagnosis against which the new test is validated (e.g., histology for cancer). | Histopathological examination [5] [7] |

The metrics of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV form an indispensable framework for evaluating diagnostic tests. While sensitivity and specificity describe the intrinsic performance of a test, PPV and NPV reveal its practical clinical value in a specific population, heavily influenced by disease prevalence. The application of these metrics in cutting-edge fields like DNA methylation research for cancer detection allows for the objective comparison of novel biomarker panels, guiding the development of more accurate and efficient diagnostic strategies. A thorough understanding of these principles, combined with rigorous experimental validation, is paramount for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to translate promising biomarkers from the laboratory into clinically useful tools that improve patient outcomes.

The Critical Role of a Gold Standard in Methylation Biomarker Validation

In the rapidly evolving field of cancer diagnostics, DNA methylation biomarkers have emerged as powerful tools for early detection, prognosis, and monitoring treatment response. These epigenetic modifications, which involve the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases in CpG dinucleotides, offer exceptional stability and are frequently altered in cancer cells [8]. The journey from biomarker discovery to clinical implementation, however, is complex and requires rigorous validation against established standards. This guide examines the critical role of gold standard methodologies in validating DNA methylation biomarkers, comparing performance metrics across technologies and sample types to inform researchers and drug development professionals engaged in sensitivity-specificity analysis of methylation detection methods.

Defining the Gold Standard in Methylation Analysis

In biomarker validation, a "gold standard" refers to the benchmark method or reference against which new tests are evaluated. For DNA methylation analysis, this encompasses multiple dimensions including the reference materials, analytical methodologies, and clinical outcomes that establish the ground truth.

The biological gold standard for cancer diagnosis remains the tissue biopsy, which provides direct morphological confirmation of disease alongside molecular data [9]. For methylation-specific studies, bisulfite sequencing is widely regarded as the reference method for base-resolution methylation mapping, with Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) providing the most comprehensive coverage [8] [9]. The bisulfite conversion process chemically deaminates unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged, allowing for precise mapping of methylation status at single-base resolution [9].

Emerging technologies such as Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) offer compelling alternatives by using enzymes rather than bisulfite to detect methylation status, thereby preserving DNA integrity—a critical advantage when working with limited liquid biopsy samples [8]. Third-generation sequencing technologies including nanopore and single-molecule real-time sequencing further expand the methodological landscape by enabling direct detection of methylation without conversion steps [8].

Essential Metrics for Biomarker Validation

Robust validation of methylation biomarkers requires assessment across multiple performance dimensions. The following metrics represent the core framework for evaluating clinical utility:

- Analytical Sensitivity: The lowest concentration of a methylated target (e.g., variant allele fraction) that can be reliably detected, crucial for early cancer detection when ctDNA fractions may be below 1% [8] [9].

- Analytical Specificity: The ability to distinguish true methylation signals from background noise and cross-reactivity with similar sequences.

- Diagnostic Sensitivity: The proportion of true positive cases correctly identified by the biomarker test.

- Diagnostic Specificity: The proportion of true negative cases correctly identified by the biomarker test.

- Reproducibility: Consistency of results across different operators, instruments, and laboratories.

- Area Under the Curve (AUC): Overall measure of diagnostic performance across all classification thresholds.

Comparative Performance of Methylation Detection Methods

The selection of methylation analysis technology significantly impacts performance characteristics, cost, and scalability. The table below summarizes key methodologies and their applications in biomarker validation.

Table 1: Comparison of DNA Methylation Analysis Technologies

| Method | Resolution | Throughput | Advantages | Limitations | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole-Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) | Single-base | High | Comprehensive genome-wide coverage; discovery of novel biomarkers [8] | High cost; computational complexity; DNA degradation from bisulfite [8] | Biomarker discovery; reference method validation |

| Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) | Single-base (CpG-rich regions) | Medium | Cost-effective; focuses on CpG islands [8] | Limited genome coverage | Targeted discovery; cancer-specific methylation profiling |

| Methylation Microarrays | Pre-defined CpG sites | High | Cost-effective for large cohorts; well-established analysis pipelines [8] | Limited to pre-designed content; cannot discover novel sites | Large-scale clinical validation studies |

| Enzymatic Methyl-Sequencing (EM-seq) | Single-base | High | Better DNA preservation than bisulfite methods [8] | newer method with less established protocols | Liquid biopsy applications with limited input material |

| Digital PCR (dPCR) | Locus-specific | Low | Absolute quantification; high sensitivity for low-abundance targets [8] | Limited to known targets; low multiplexing capability | Clinical validation; monitoring minimal residual disease |

| Methylation-Specific PCR (qMSP) | Locus-specific | High | Simple; cost-effective; high sensitivity [10] | Qualitative/semi-quantitative; prone to false positives without careful optimization | Clinical assay development; high-throughput screening |

Experimental Workflows for Biomarker Validation

A robust validation framework for methylation biomarkers follows a structured pathway from discovery to clinical implementation. The diagram below illustrates this multi-stage process.

Gold Standard Biomarker Panels in Clinical Development

Several methylation biomarker panels have advanced through rigorous validation and demonstrate the performance achievable with comprehensive development. The table below highlights representative examples across cancer types.

Table 2: Clinically Validated Methylation Biomarker Panels

| Cancer Type | Biomarker Panel | Sample Type | Performance | Validation Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Colorectal Cancer | SDC2, SFRP2, SEPT9 [9] | Feces, Blood [9] | Sensitivity: 86.4%\nSpecificity: 90.7% (ColonSecure study) [9] | FDA-approved (Epi proColon) and Breakthrough Devices (Shield) [8] |

| Prostate Cancer | GSTP1, CCND2, APC, RASSF1 [10] | Tissue, Liquid Biopsy [10] | AUC: 0.937 (GSTP1 + CCND2 combination) [10] | Multiple panels in validation; tissue confirmed |

| Breast Cancer | 15-marker ctDNA panel [9] | Blood (ctDNA) [9] | AUC: 0.971 [9] | Discovery and initial validation |

| Bladder Cancer | CFTR, SALL3, TWIST1 [9] | Urine [9] | Superior sensitivity in urine vs. blood [8] | FDA Breakthrough Device designation [8] |

| Esophageal Squamous Cell Carcinoma | 12-CpG panel [9] | Tissue [9] | AUC: 0.966 [9] | TCGA data validation |

| Multiple Cancers | Multi-cancer early detection test [8] | Blood (plasma) [8] | Varies by cancer type and stage | FDA Breakthrough Device (Galleri, OverC) [8] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful methylation biomarker validation requires carefully selected reagents and platforms. The following table details essential components of the methylation researcher's toolkit.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Methylation Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kit | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracils | Critical step for bisulfite-based methods; optimized kits minimize DNA degradation [9] |

| DNA Methyltransferases (DNMTs) | Enzymes for methylation detection in enzyme-based methods | DNMT1, DNMT3A, DNMT3B for maintenance and de novo methylation studies [10] |

| Methylation-Specific Restriction Enzymes | Cleavage at specific methylation patterns | Used in enrichment-based methods like MeDIP-seq [8] |

| MethylBinding Domain (MBD) Proteins | Enrichment of methylated DNA fragments | Used in MBD-seq and related capture techniques [8] |

| Digital PCR Master Mix | Absolute quantification of methylated alleles | Essential for high-sensitivity detection of low-frequency methylation events in liquid biopsies [8] |

| Bisulfite-Treated Control DNA | Positive and negative controls for assay validation | Commercially available fully methylated and unmethylated DNA standards |

| Next-Generation Sequencing Library Prep Kits | Preparation of bisulfite or enzyme-converted DNA for sequencing | Specialized kits account for reduced sequence complexity post-conversion |

| Cell-Free DNA Collection Tubes | Stabilization of blood samples for liquid biopsy | Preserves ctDNA profile; critical for multi-center clinical trials [8] |

Method Selection Framework for Validation Studies

Choosing the appropriate methodology depends on the specific validation objectives, sample type, and resource constraints. The decision pathway below provides guidance for method selection.

The validation of DNA methylation biomarkers against rigorous gold standards remains fundamental to translating epigenetic discoveries into clinically impactful tools. As detection technologies evolve and liquid biopsy applications expand, maintaining stringent validation frameworks becomes increasingly critical. Researchers must carefully match method selection to validation objectives, from initial discovery using comprehensive sequencing approaches to clinical implementation with targeted, high-sensitivity platforms. The continued refinement of both analytical methods and clinical validation pathways will accelerate the adoption of methylation biomarkers in precision oncology, ultimately improving early cancer detection, monitoring, and patient outcomes.

In the pursuit of diagnostic accuracy, researchers and clinicians have long relied on heuristic tools to quickly interpret test results. Among the most recognized are SnNOut (Sensitive, Negative, Rule OUT) and SpPIn (Specific, Positive, Rule IN), mnemonics that provide a simplified framework for diagnostic reasoning [11]. These rules propose that a highly sensitive test, when negative, can effectively rule out a disease, while a highly specific test, when positive, can rule it in [12]. For decades, these principles have been taught in evidence-based medicine and remain deeply embedded in clinical practice and research methodology.

The application of these diagnostic rules extends beyond traditional clinical settings into advanced research domains, including methylation detection methods and epigenetics research. In molecular diagnostics, accurately interpreting the results of assays that detect methylation patterns—crucial for understanding gene expression regulation in cancer development, neurological disorders, and drug response—requires a sophisticated understanding of test performance characteristics [13]. As researchers develop increasingly refined epigenetic biomarkers, the limitations of simplistic diagnostic heuristics become more apparent, necessitating a more nuanced approach to diagnostic test interpretation that incorporates pretest probability, likelihood ratios, and the specific research context [14] [15].

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Sensitivity and Specificity

Sensitivity and specificity are foundational biometric parameters that describe the inherent accuracy of a diagnostic test. Sensitivity (true positive rate) measures a test's ability to correctly identify individuals who have the disease, calculated as the proportion of diseased individuals who test positive [12] [16]. Mathematically, sensitivity = True Positives/(True Positives + False Negatives). A test with 95% sensitivity will detect 95 of 100 truly diseased individuals, missing 5 (false negatives).

Specificity (true negative rate) measures a test's ability to correctly identify individuals without the disease, calculated as the proportion of non-diseased individuals who test negative [12] [16]. Mathematically, specificity = True Negatives/(True Negatives + False Positives). A test with 90% specificity will correctly classify 90 of 100 healthy individuals, while incorrectly classifying 10 healthy individuals as diseased (false positives).

These characteristics are typically represented in a 2x2 contingency table that cross-tabulates test results with true disease status:

Table 1: Standard 2x2 Contingency Table for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Disease Present | Disease Absent | |

|---|---|---|

| Test Positive | True Positive (A) | False Positive (B) |

| Test Negative | False Negative (C) | True Negative (D) |

SnNOut and SpPIn Rules

The SnNOut mnemonic encapsulates the principle that when a test with high Sensitivity returns a Negative result, it can rule Out the target condition [11] [12]. This rule is clinically valuable because a highly sensitive test rarely misses individuals with the disease, so a negative result provides confidence that the disease is absent.

The SpPIn mnemonic encapsulates the principle that when a test with high Specificity returns a Positive result, it can rule In the target condition [11] [12]. This is valuable because a highly specific test rarely incorrectly labels healthy individuals as diseased, so a positive result strongly suggests the disease is present.

Table 2: Examples of Tests with SnNOut and SpPIn Properties

| Test | Target Condition | Sensitivity | Specificity | Clinical Rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ottawa Ankle Rules [12] | Ankle or midfoot fracture | 99% (92-100%) | 39% (34-45%) | SnNOut (negative test rules out fracture) |

| CAGE Questionnaire (≥3 positives) [11] | Alcohol dependence | Not specified | >99% | SpPIn (positive test rules in alcoholism) |

| Loss of retinal vein pulsation [11] [12] | Increased intracranial pressure | 100% (92-100%) | 88% (81-93%) | SnNOut (presence of pulsation rules out increased ICP) |

Figure 1: This decision pathway illustrates the clinical application of SpPIn and SnNOut rules. The process begins with evaluating a test's sensitivity and specificity characteristics, then applying the appropriate heuristic based on the test result. Note that these rules only apply when tests demonstrate appropriately high sensitivity or specificity values.

Critical Limitations and Methodological Challenges

Fundamental Statistical Flaws

Despite their widespread adoption, SpPIn and SnNOut present significant limitations that can lead to diagnostic errors. A primary concern is that neither sensitivity nor specificity should be considered in isolation when evaluating a test's diagnostic utility [14]. These characteristics represent interdependent aspects of test performance, and focusing on one while ignoring the other provides an incomplete picture.

Research demonstrates that a test's utility for ruling in or ruling out disease depends fundamentally on the post-test probability rather than isolated sensitivity or specificity values [14]. The following comparison illustrates this critical limitation:

Table 3: Test Performance Comparison Demonstrating Flaw in SpPIn/SnNOut Logic

| Test | Sensitivity | Specificity | LR+ | LR- | SpPIn Recommendation | SnNOut Recommendation | Actual Best Test For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test A | 30% | 95% | 6.0 | 0.74 | Yes (rules in) | No | Neither |

| Test B | 95% | 30% | 1.4 | 0.17 | No | Yes (rules out) | Neither |

| Test C | 90% | 90% | 9.0 | 0.11 | No | No | Both ruling in and out |

As shown in Table 3, SpPIn would incorrectly identify Test A as best for ruling in disease (due to highest specificity), while SnNOut would incorrectly identify Test B as best for ruling out disease (due to highest sensitivity). In reality, Test C outperforms both for ruling in and ruling out disease because it generates both the highest post-test probability when positive (due to LR+ = 9.0) and the lowest post-test probability when negative (due to LR- = 0.11) [14].

Pretest Probability and Prevalence Effects

The pretest probability (prevalence) of a condition substantially influences the predictive values of diagnostic tests, creating a critical limitation for SpPIn and SnNOut that these heuristics fail to address [15] [17]. Even tests with apparently excellent sensitivity and specificity characteristics can perform poorly when disease prevalence is very low or very high.

A compelling example comes from COVID-19 antibody testing during the pandemic. With a test demonstrating 99% sensitivity and 99% specificity, and a population prevalence of 0.541%, the positive predictive value (PPV) would be only 35% despite the high specificity [17]. This means that only 35% of positive test results would represent true infections, making the test inadequate for "ruling in" prior infection despite the seemingly high specificity that would suggest SpPIn applicability.

The mathematical relationship between prevalence and predictive values can be expressed as:

- Positive Predictive Value (PPV) = (Sensitivity × Prevalence) / [(Sensitivity × Prevalence) + (1 - Specificity) × (1 - Prevalence)]

- Negative Predictive Value (NPV) = [Specificity × (1 - Prevalence)] / [(Specificity × (1 - Prevalence)) + (1 - Sensitivity) × Prevalence]

This demonstrates that as prevalence decreases, PPV decreases (more false positives), and as prevalence increases, NPV decreases (more false negatives) [15].

Problems with Test Dichotomization

Most diagnostic tests in practice are not truly dichotomous but exist on a spectrum of possible results [14]. Physical exam maneuvers often have ordinal outcomes (e.g., "negative," "indeterminate," "positive"), while laboratory tests typically produce continuous numerical values. The process of dichotomizing these continuous or multilevel test results into simple positive/negative categories introduces measurement error and discards valuable diagnostic information.

Research on ultrasound measurement of jugular venous pressure exemplifies this limitation. When dichotomized, the test demonstrated modest sensitivity (73%) and specificity (79%), with likelihood ratios that would not be considered particularly helpful (LR+ = 3.4, LR- = 0.34) [14]. However, when analyzed as six distinct levels of test results, the likelihood ratios ranged from zero to infinity, revealing substantially more diagnostic utility than apparent from the dichotomized approach [14].

In molecular diagnostics, including methylation detection methods, this limitation is particularly relevant. Methylation levels typically exist on a continuous spectrum, and dichotomizing results into "methylated" or "unmethylated" categories may obscure clinically significant patterns and reduce test accuracy [13].

Advanced Diagnostic Interpretation Frameworks

Likelihood Ratios and Bayesian Analysis

Likelihood ratios (LRs) provide a superior framework for diagnostic test interpretation as they incorporate both sensitivity and specificity into a single measure that can be directly applied to modify disease probability [14] [15] [18]. The likelihood ratio for a given test result represents the probability of that result among patients with the disease divided by the probability of the same result among patients without the disease.

The fundamental Bayesian equation for diagnostic test interpretation is:

Pretest Odds × Likelihood Ratio = Posttest Odds

This calculation can be simplified using a nomogram or online calculators, eliminating the need for manual probability-odds conversions [14]. Likelihood ratios are interpreted according to their magnitude:

Table 4: Interpretation of Likelihood Ratios for Diagnostic Test Results

| LR Value | Interpretation | Effect on Posttest Probability |

|---|---|---|

| >10 | Large increase | Conclusive shift |

| 5-10 | Moderate increase | Moderate shift |

| 2-5 | Small increase | Small but sometimes important shift |

| 1-2 | Minimal change | Rarely important |

| 0.5-1 | Minimal change | Rarely important |

| 0.1-0.5 | Small decrease | Small but sometimes important shift |

| 0.1-0.2 | Moderate decrease | Moderate shift |

| <0.1 | Large decrease | Conclusive shift |

Research Methodology and Experimental Protocols

Implementing robust diagnostic accuracy studies requires careful methodological planning to minimize bias and maximize generalizability. Key considerations include:

Optimal Study Design: The prospective cohort study represents the optimal design for diagnostic accuracy research, wherein the test(s) and reference standard undergo prospective blind comparison in a clinically relevant patient sample [16]. This design minimizes verification bias and ensures the results reflect real-world application.

Sample Size and Power Considerations: Most diagnostic accuracy studies are underpowered, compromising the precision of sensitivity and specificity estimates [18]. Appropriate power calculations must be conducted a priori to ensure sufficient participants are enrolled. For example, a study aiming to demonstrate 95% sensitivity with a 90% lower confidence limit would require approximately 298 participants [18].

Reference Standard Application: The reference standard must be applied consistently to all study participants, independent of the diagnostic test results, with blinding maintained between test and reference standard interpreters [16].

Spectrum of Participants: The study population should represent the full spectrum of patients on whom the test will be used in practice, including mild, moderate, and severe cases, to avoid spectrum bias that inflates accuracy measures [12].

Figure 2: Recommended workflow for conducting diagnostic test accuracy studies, emphasizing methodological rigor to minimize bias and maximize the clinical applicability of findings.

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 5: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Diagnostic Test Evaluation

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standard Test | Provides definitive disease classification | Gold standard comparison for new index tests |

| DNA Methylation Arrays | Genome-wide methylation profiling | Epigenetic association studies [13] |

| Linear Mixed Effect Models | Accounts for familial correlations in data | Genetic and epigenetic studies with related participants [13] |

| QUADAS-2 Tool | Quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies | Methodological quality appraisal [18] |

| Statistical Software (R, Python) | Data analysis and accuracy metric calculation | All statistical analyses and visualization |

| Sample Size Calculation Tables | Determines minimum participant numbers | Study design phase to ensure adequate power [18] |

| Online Nomograms/Calculators | Bayesian probability revision | Clinical application of likelihood ratios [14] |

The SnNOut and SpPIn rules, while mnemonically appealing and easily remembered, present significant limitations for modern diagnostic practice and research. These heuristics fail to account for the critical influences of pretest probability, the interdependent nature of sensitivity and specificity, and the continuous nature of most diagnostic tests. In molecular research, including methylation detection methodologies, these limitations are particularly problematic given the subtle and continuous nature of epigenetic markers.

A superior approach incorporates likelihood ratios within a Bayesian framework, enabling quantitative revision of disease probability based on test results while considering both test characteristics and population context [14] [18]. Additionally, researchers should avoid arbitrary dichotomization of continuous test results, instead preserving multiple test thresholds or utilizing the full spectrum of values to maximize diagnostic information [14] [13].

As diagnostic technologies evolve, particularly in epigenetic research where methylation patterns serve as biomarkers for disease detection, prognosis, and therapeutic monitoring, moving beyond simplistic heuristics toward more sophisticated probabilistic reasoning becomes increasingly essential for accurate diagnosis and effective patient management.

DNA methylation, the process of adding a methyl group to a cytosine base in DNA, has emerged as a cornerstone of cancer biomarker research. This epigenetic modification regulates gene expression without altering the underlying DNA sequence and possesses three fundamental properties that make it exceptionally powerful for clinical applications: inherent molecular stability, early appearance during carcinogenesis, and convenient detectability in liquid biopsies. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these properties is crucial for developing the next generation of cancer diagnostics and monitoring tools. The stability of the DNA molecule itself, combined with the cancer-specific nature of methylation patterns, provides a robust foundation for assays that can detect malignancies years before clinical symptoms manifest [8] [19]. This review systematically examines the evidence supporting methylation's biomarker utility, compares detection methodologies, and provides practical experimental guidance for leveraging this powerful tool in cancer research.

Key Properties of DNA Methylation as a Biomarker

Exceptional Biological Stability

The stability of DNA methylation biomarkers operates on two distinct levels: molecular and pattern stability. The DNA double helix provides structural stability far superior to single-stranded nucleic acids or proteins, protecting methylated cytosines from degradation during sample collection, storage, and processing [8]. This molecular resilience is particularly valuable for liquid biopsy applications where circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) fragments are subject to rapid clearance from the bloodstream, with half-lives estimated from minutes to a few hours [8].

Longitudinal studies have demonstrated that while the blood methylome shows considerable dynamism over time, a specific subset of methylation sites exhibits remarkable temporal stability. A comprehensive 2024 analysis of blood DNA methylation across three cohorts revealed that out of thousands of probes analyzed, 239 highly stable probes were identified that maintained consistent methylation patterns over periods exceeding one year, with an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) >0.74 and mean absolute difference <0.01 [20]. These stable probes were predominantly influenced by genomic variation, suggesting that genetics provides a stable foundation upon which methylation biomarkers can be built for reliable longitudinal monitoring.

Early Appearance in Carcinogenesis

DNA methylation alterations represent some of the earliest molecular events in cancer development, often preceding clinical diagnosis by several years. The potential for early detection was dramatically demonstrated in the Taizhou Longitudinal Study, where the PanSeer assay detected methylation changes in five common cancer types (stomach, esophageal, colorectal, lung, and liver) up to four years before conventional diagnosis with 95% sensitivity in asymptomatic individuals who later developed cancer [19].

The biological basis for this early appearance lies in the fundamental role DNA methylation plays in tumor initiation. Two complementary patterns emerge early in carcinogenesis: global hypomethylation, which leads to genomic instability and oncogene activation, and focal hypermethylation of CpG islands in promoter regions of tumor suppressor genes, resulting in their transcriptional silencing [21] [22] [23]. These changes occur during the precancerous or early cancer stages [9], making them ideal sentinels for identifying molecular transformations long before they manifest as clinically detectable tumors.

Detectability in Liquid Biopsies

The advent of liquid biopsy platforms has revolutionized cancer detection by enabling non-invasive access to tumor-derived genetic material. DNA methylation biomarkers are particularly well-suited for liquid biopsy applications due to several advantageous properties. Methylation patterns can be detected in extremely low concentrations of circulating tumor DNA, with advanced methods like the PanSeer assay demonstrating detection capability at cancer DNA fractions as low as 0.1% [19].

Different bodily fluids offer varying advantages for methylation-based detection, often related to anatomical proximity to the tumor origin. For example, urine shows superior performance for bladder cancer detection, with one study reporting 87% sensitivity for mutation detection in urine versus only 7% in plasma [8]. Similarly, bile outperforms plasma for biliary tract cancers, stool provides superior detection for colorectal cancer, and cerebrospinal fluid offers enhanced sensitivity for central nervous system malignancies [8]. This principle of "local liquid biopsy" sources often provides higher biomarker concentration and reduced background noise compared to systemic blood samples.

Table 1: Comparison of Liquid Biopsy Sources for Methylation Biomarker Detection

| Liquid Biopsy Source | Advantages | Ideal Cancer Applications | Detection Sensitivity Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blood (Plasma) | Systemic circulation, captures tumors regardless of location | Multi-cancer early detection, monitoring | PanSeer: 88% detection for 5 cancers post-diagnosis [19] |

| Urine | Fully non-invasive, high patient compliance | Bladder, prostate, renal cancers | TERT mutations: 87% sensitivity in urine vs 7% in plasma [8] |

| Sputum | Direct contact with respiratory epithelium | Lung cancer | SHOX2 methylation: 67% sensitivity at 90% specificity [22] |

| Stool | Direct sampling of gastrointestinal tract | Colorectal cancer | Cologuard: 92.3% sensitivity for cancer detection [24] |

| Bile | Anatomical proximity to hepatobiliary system | Cholangiocarcinoma, liver cancer | Superior mutation detection vs plasma [8] |

Methylation Biomarkers Across Cancer Types

Extensive research has identified specific DNA methylation biomarkers with demonstrated clinical utility across numerous cancer types. The table below summarizes well-validated methylation markers and their performance characteristics in different sample types.

Table 2: Validated DNA Methylation Biomarkers Across Different Cancers

| Cancer Type | Methylation Biomarkers | Sample Type | Performance Metrics | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lung Cancer | SHOX2, RASSF1A, DAPK, MGMT | Plasma, sputum, BALF | SHOX2: 67% sensitivity at 90% specificity; RASSF1A panel: 73% sensitivity, 82% specificity [21] [22] | |

| Colorectal Cancer | SEPT9, SDC2, BMP3, NDRG4 | Blood, stool | mSEPT9: pooled sensitivity 0.69, specificity 0.92; SDC2: sensitivity 0.81, specificity 0.95 [9] [24] | |

| Breast Cancer | TRDJ3, PLXNA4, KLRD1, KLRK1 | PBMC, tissue, blood | 4-marker panel: 93.2% sensitivity, 90.4% specificity [9] | |

| Bladder Cancer | CFTR, SALL3, TWIST1 | Urine | Multiple studies showing high sensitivity in urine samples [9] | |

| Liver Cancer | SEPT9, BMPR1A, PLAC8 | Tissue, blood | Varies by marker and study [9] | |

| Pancreatic Cancer | PRKCB, KLRG2, ADAMTS1, BNC1 | Tissue, blood | Varies by marker and study [9] |

The clinical translation of these biomarkers is already underway, with several methylation-based tests receiving regulatory approval. Examples include Epi proColon and Cologuard for colorectal cancer screening, and Shield and Galleri which have received FDA Breakthrough Device designation [8] [24]. The ongoing development of multi-cancer early detection (MCED) tests represents perhaps the most promising application, with the potential to revolutionize cancer screening paradigms.

Detection Technologies and Methodologies

Comparison of Methylation Analysis Methods

The selection of appropriate detection methodology is critical for successful methylation biomarker research. The table below compares the major categories of DNA methylation analysis techniques, each with distinct advantages and limitations for specific applications.

Table 3: DNA Methylation Detection Technologies and Their Characteristics

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Resolution | Advantages | Disadvantages | Best Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion-Based | Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS), Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS), Bisulfite pyrosequencing | Single-base | Gold standard, comprehensive coverage | DNA degradation, complex data analysis | Discovery phase, biomarker identification [9] [23] |

| Restriction Enzyme-Based | Methylation-Sensitive Restriction Enzymes (HpaII, MspI), HELP Assay, MRE-Seq | Site-specific (depends on enzyme) | No bisulfite conversion, preserves DNA integrity | Limited to enzyme recognition sites | Targeted validation, clinical assays [25] [23] |

| Affinity Enrichment-Based | Methylated DNA Immunoprecipitation (MeDIP), MBD-seq | Regional | No conversion, works with degraded DNA | Lower resolution, antibody variability | Genome-wide methylation patterns [23] |

| Microarray-Based | Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC | Single-base (but predefined sites) | High-throughput, cost-effective for large studies | Limited to predefined CpG sites | Large cohort studies, epidemiological research [20] [23] |

| Third-Generation Sequencing | Nanopore sequencing, SMRT sequencing | Single-base | Direct detection, long reads | Higher error rates, specialized equipment | Emerging technology, comprehensive analysis [9] |

Experimental Workflow for Methylation Biomarker Validation

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for developing and validating methylation biomarkers in liquid biopsies, synthesizing approaches from multiple studies:

Figure 1: Methylation Biomarker Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful methylation biomarker research requires specialized reagents and tools. The following table details essential components of the methylation researcher's toolkit:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Methylation Analysis

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Methylation-Sensitive Enzymes | HpaII, MspI (isoschizomer pair) [25] | Differential digestion based on methylation status | HpaII cleaves unmethylated CCGG sites; MspI cleaves regardless of methylation |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Various commercial kits | Chemical conversion of unmethylated C to U | Conversion efficiency critical; newer enzymatic methods reduce DNA damage [24] |

| Methylated DNA Controls | Enzymatically methylated DNA (M.SssI) [25] | Positive controls for methylation assays | Ensures assay specificity and sensitivity |

| Targeted Panels | Ion AmpliSeq Methylation Panel for Cancer Research [26] | Multiplexed targeted methylation analysis | Cost-effective for focused studies; requires low DNA input |

| 5hmC Discrimination Tools | Glucosylation step + MspJI digestion [25] | Distinguishes 5hmC from 5mC | Emerging evidence for 5hmC as distinct biomarker [24] |

| Library Preparation Kits | Singlera method (semi-targeted PCR) [19] | Efficient library construction from limited DNA | Higher molecular recovery rate vs conventional methods |

Case Studies: Methylation Biomarkers in Action

PanSeer Multi-Cancer Early Detection Assay

The PanSeer assay represents a landmark advancement in methylation-based cancer detection. This test utilizes a targeted approach focusing on 595 genomic regions containing 11,787 CpG sites identified from public databases and internal sequencing data as consistently aberrant across multiple cancers [19]. The technical approach employs a semi-targeted PCR method that requires only a single ligation event, enabling high molecular recovery rates critical for detecting the scarce ctDNA in early-stage cancers.

In validation studies using plasma samples from the Taizhou Longitudinal Study, PanSeer demonstrated 88% sensitivity for detecting post-diagnosis patients with five common cancer types (stomach, esophageal, colorectal, lung, and liver) at 96% specificity [19]. Most impressively, the assay detected 95% of cancers in asymptomatic individuals who were later diagnosed within 1-4 years, providing compelling evidence for the early appearance of methylation changes in carcinogenesis.

MRE-Seq for Lung Cancer Detection

The MRE-Seq (Methylation-sensitive Restriction Enzyme digestion followed by Sequencing) protocol exemplifies the restriction enzyme-based approach to methylation analysis in liquid biopsies. This method achieved an AUC of 0.956 with 66.3% sensitivity for lung cancer detection at 99.2% specificity in a validation study [24]. The technique showed consistent performance across stages I-IV, with sensitivities ranging from 44.4% to 78.9%, demonstrating particular utility for early-stage detection where treatment options are most effective.

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual relationship between methylation biomarker properties and their clinical utility:

Figure 2: Methylation Properties Driving Clinical Applications

DNA methylation embodies the ideal characteristics of a cancer biomarker: early appearance during tumorigenesis, molecular stability that withstands analytical processing, and convenient detectability in minimally invasive liquid biopsies. The convergence of these properties, coupled with advancing detection technologies, has positioned methylation biomarkers at the forefront of cancer diagnostics research.

Future directions in this field include the refinement of multi-cancer early detection tests, the development of tissue-of-origin determination algorithms based on methylation patterns, and the integration of methylation biomarkers with other molecular markers (mutations, fragmentomics) to enhance sensitivity and specificity. Additionally, the discrimination between 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine shows promise as a more specific biomarker, particularly for tracking disease progression [24].

For researchers and drug development professionals, methylation biomarkers offer powerful tools not only for early detection but also for monitoring treatment response, detecting minimal residual disease, and understanding resistance mechanisms. As large-scale longitudinal studies continue to validate the clinical utility of these biomarkers, and as detection methods become more sensitive and cost-effective, methylation-based liquid biopsies are poised to transform cancer management across the clinical continuum.

Technology Landscape: Performance Profiles of Modern Methylation Detection Platforms

DNA methylation, the addition of a methyl group to the fifth carbon of a cytosine residue, is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism regulating gene expression, genomic imprinting, and cellular differentiation [27]. Bisulfite conversion-based sequencing methods represent the gold standard for detecting this modification at single-base resolution, a critical capability for understanding its functional consequences [28] [29]. The fundamental principle involves treating DNA with sodium bisulfite, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracil (read as thymine after PCR amplification), while methylated cytosines remain unchanged [28] [30]. This process creates sequence polymorphisms that allow precise quantification of methylation status at individual cytosine sites through subsequent sequencing [31].

The two primary bisulfite sequencing approaches discussed in this guide—Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) and Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS)—offer this single-base resolution but differ substantially in genomic coverage, application focus, and cost structure [32] [33]. While WGBS provides a comprehensive methylome map, RRBS employs a strategic enrichment strategy to target functionally relevant regions at reduced cost [34] [35]. Understanding their technical performance characteristics is essential for researchers investigating epigenetic mechanisms in development, disease, and therapeutic intervention.

Experimental Methodologies and Workflows

Whole Genome Bisulfite Sequencing (WGBS) Protocol

The standard WGBS protocol involves fragmenting genomic DNA via sonication or enzymatic digestion, followed by library preparation with bisulfite-converted adapters [30]. Critical steps include:

- DNA Fragmentation: 50-500 ng of high-quality genomic DNA is fragmented to 200-300 bp using Covaris shearing or nebulization.

- Bisulfite Conversion: Fragmented DNA undergoes bisulfite treatment using commercial kits (e.g., Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation-Gold or Qiagen EpiTect), typically involving 3-16 hour incubations at temperatures ranging from 50°C to 65°C [30]. This conversion step introduces substantial DNA degradation (up to 90% DNA loss) through depyrimidination, necessitating careful optimization [30] [36].

- Library Amplification: Converted DNA is PCR-amplified (10-18 cycles) using bisulfite-converted polymerase systems (e.g., Pfu Turbo Cx or KAPA HiFi Uracil+) [30].

- Sequencing: Libraries are sequenced on Illumina platforms, with recommended coverage of 20-30x for mammalian genomes, requiring approximately 800 million to 1 billion 100bp reads [31].

Protocol variations include pre-bisulfite adapter tagging (which requires higher DNA input) versus post-bisulfite adapter tagging (PBAT) methods that reduce DNA loss but may introduce different biases [30].

Reduced Representation Bisulfite Sequencing (RRBS) Protocol

The RRBS methodology utilizes restriction enzyme digestion to selectively target CpG-rich regions:

- Enzymatic Digestion: Genomic DNA (10-100 ng) is digested with MspI (recognition site: CCGG), a methylation-insensitive restriction enzyme that cuts frequently in CpG-rich regions [34] [35].

- Size Selection: Digested fragments undergo strict size selection (40-220 bp) to enrich for CpG islands and promoter regions [32] [35].

- Bisulfite Conversion: Size-selected fragments undergo standard bisulfite conversion as described for WGBS.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Libraries are prepared with standard bisulfite-converted adapters and sequenced on Illumina platforms, typically requiring 10-50 million reads per sample depending on the organism [31].

Recent protocol enhancements recommend paired-end sequencing for RRBS to better distinguish single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) from true methylation events, counter to conventional practice [34].

The graphical workflow below illustrates the key procedural differences between WGBS and RRBS:

Technical Performance Comparison

Genomic Coverage and Regional Specificity

The fundamental distinction between WGBS and RRBS lies in their genomic coverage strategies and the resulting methylation profiles:

Table 1: Genomic Coverage and Regional Specificity Comparison

| Parameter | WGBS | RRBS |

|---|---|---|

| Genomic Coverage | 80-95% of all CpG sites [29] [33] | 1.6-12% of all CpG sites (species-dependent) [33] |

| CpG Island Coverage | >95% [32] | 85-90% [31] |

| CpG Shore Coverage | Comprehensive [32] | Limited [32] |

| Open Sea Regions | 88% of sequencing reads [35] | Minimal coverage [35] |

| Repetitive Elements | 45% of interrogated CpGs in repeats [33] | Proportional to genome-wide coverage [33] |

| Methylation Context | CpG, CHG, and CHH contexts [31] | Primarily CpG context [34] |

WGBS provides truly genome-wide coverage, capturing methylation patterns across all genomic contexts including intergenic regions, repetitive elements, and low-CpG-density "open sea" regions [32] [33]. In contrast, RRBS strategically targets CpG-rich regions, with approximately 34% of reads originating from CpG islands, 12% from shores, and 13% from shelves, representing a 12.8-fold enrichment over WGBS in CpG islands [35]. This targeted approach comes at the cost of comprehensive coverage but provides enhanced depth in functionally significant regulatory regions.

Detection Sensitivity, Specificity, and Quantitative Performance

Both techniques offer single-base resolution, but their detection characteristics differ significantly:

Table 2: Sensitivity, Specificity, and Quantitative Performance

| Performance Metric | WGBS | RRBS |

|---|---|---|

| Single-Base Resolution | Yes [32] | Yes [32] |

| Detection of Intermediate Methylation | Comprehensive capture [34] | Greatly reduced prevalence [34] |

| Mapping Efficiency | 45% lower than BWA meth in comparative studies [34] | Varies by alignment tool [34] |

| False Positive Sources | Incomplete bisulfite conversion, particularly in GC-rich regions [29] [30] | SNP misidentification as methylation events [34] |

| Read Depth Requirements | 20-30x for mammalian genomes [31] | Lower due to targeted nature [31] |

| Methylation Quantification Accuracy | High at sufficient depth (>20x) [31] | High for covered regions [35] |

Notably, RRBS demonstrates a systematic reduction in detecting loci with intermediate methylation levels (those with proportions between fully methylated and unmethylated states), which may have important implications for functional interpretations of epigenetic heterogeneity [34]. WGBS more accurately captures this biological nuance but requires substantially greater sequencing resources.

Technical Reproducibility and Analytical Considerations

Technical variation in bisulfite sequencing arises from multiple sources, with conversion efficiency being a critical factor. Both methods typically achieve >99% conversion efficiency when optimized properly, as measured by spike-in controls [28] [30]. However, the extensive fragmentation from bisulfite treatment (up to 90% DNA degradation) introduces coverage biases, particularly in high-GC regions where base composition becomes unbalanced [30] [36].

Bioinformatic processing significantly influences data quality. Bismark, the most widely used methylation caller, demonstrates 82% concordance for CpG methylation levels compared to alternative pipelines [33]. Alignment tools substantially impact mapping efficiency, with BWA meth providing 45% higher mapping efficiency than Bismark in comparative studies [34]. Depth filtering parameters dramatically affect CpG site recovery, particularly for WGBS, with read depth thresholds between 5-20 reads per site commonly applied, though often without statistical justification [31].

Practical Implementation Considerations

Sample Requirements and Input Flexibility

Table 3: Sample Requirements and Practical Considerations

| Parameter | WGBS | RRBS |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Input Requirements | 0.5-5 μg (pre-BS); 100-200 cells (post-BS) [30] | 10-100 ng [35] |

| DNA Quality | High molecular weight preferred | More tolerant of partial degradation |

| Sample Multiplexing Capacity | Lower due to sequencing depth requirements | Higher due to reduced sequencing per sample |

| Optimal Sample Size | Smaller cohorts (due to cost constraints) [34] | Larger cohorts for population studies [34] |

| Suitability for FFPE Samples | Challenging due to DNA damage [28] | More suitable with protocol modifications [28] |

| Cell-Free DNA Applications | Limited due to cost and input requirements | Specialized adaptations (cfMethyl-Seq) perform well [35] |

WGBS demands substantially higher DNA inputs, particularly for pre-bisulfite adapter tagging protocols, while post-bisulfite approaches like PBAT enable sequencing of low-input samples (100-200 cells) [30]. RRBS is more adaptable to challenging sample types, including formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues and cell-free DNA, with specialized modifications like cfMethyl-Seq developed specifically for liquid biopsy applications [28] [35].

Cost and Resource Analysis

The economic considerations of bisulfite sequencing methods directly impact experimental design:

- Sequencing Costs: WGBS requires 800 million to 1 billion reads for mammalian genomes, while RRBS typically requires 10-50 million reads—a 20-50 fold reduction in sequencing volume [31] [35].

- Library Preparation Costs: WGBS reagents are generally more expensive due to larger reaction volumes and specialized polymerases needed to handle bisulfite-converted templates [30].

- Computational Resources: WGBS demands substantial computational infrastructure for data storage and alignment, with file sizes typically 5-10 times larger than RRBS datasets [34].

- Cost Efficiency: RRBS provides the lowest cost per CpG covered in CpG islands, while WGBS becomes more cost-effective when considering genome-wide coverage [33].

For large-scale epidemiological or ecological studies requiring hundreds of samples, RRBS often represents the only feasible approach due to its substantially lower per-sample cost [34] [31].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Bisulfite Sequencing

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation-Gold; Qiagen EpiTect; Sigma-Aldrich Imprint DNA Modification Kit | Convert unmethylated cytosines to uracil; kit performance varies in conversion efficiency and DNA damage [30] |

| Methylation-Insensitive Restriction Enzymes | MspI (for RRBS) | Digests DNA at CCGG sites regardless of methylation status; enables targeted enrichment in RRBS [35] |

| Specialized Polymerases | Pfu Turbo Cx; KAPA HiFi Uracil+; JumpStart | Amplifies bisulfite-converted DNA with reduced bias; critical for maintaining library complexity [30] |

| Library Preparation Kits | NEBNext Ultra II; Swift Accel-NGS Methyl-Seq; TruSeq DNA Methylation | Prepares sequencing libraries from bisulfite-converted DNA; impacts final library complexity and bias [30] |

| Bioinformatic Tools | Bismark; BWA-meth; MethylDackel; BS-Seeker3 | Aligns bisulfite-converted reads and extracts methylation calls; mapping efficiency varies substantially [34] |

| Spike-In Controls | Lambda DNA; PCR products with known methylation status | Monitors bisulfite conversion efficiency; essential for quality control [28] |

Emerging Alternatives and Future Directions

While bisulfite-based methods currently represent the gold standard for DNA methylation analysis, enzymatic conversion approaches are emerging as promising alternatives. Enzymatic Methyl-seq (EM-seq) utilizes TET2 oxidation and APOBEC deamination to identify methylated cytosines without DNA damage [28] [29]. Comparative studies demonstrate EM-seq provides higher mapping efficiency, superior CpG detection (54 million versus 36 million CpGs at 1x coverage), and reduced GC bias compared to WGBS [29] [36]. Similarly, TET-assisted pyridine borane sequencing (TAPS) offers an alternative enzymatic approach but requires custom enzyme production [36].

Third-generation sequencing technologies, particularly Oxford Nanopore Technologies, enable direct methylation detection without conversion by measuring electrical current deviations as DNA passes through nanopores [29]. While currently exhibiting lower agreement with bisulfite methods (82% concordance), these approaches excel in characterizing challenging genomic regions and detecting methylation in long-range contexts [29].

For most applications requiring single-base resolution of DNA methylation, the choice between WGBS and RRBS involves balancing comprehensive coverage against practical constraints. WGBS remains optimal for discovery-oriented studies requiring complete methylome characterization, while RRBS provides a cost-effective alternative for focused investigations of CpG-rich regulatory regions, particularly in large-scale population studies [34] [31].

DNA methylation is a fundamental epigenetic mechanism involving the addition of a methyl group to cytosine bases, primarily at cytosine-phosphate-guanine (CpG) dinucleotides, which plays a crucial role in gene regulation, cellular differentiation, and disease pathogenesis [37] [27]. In the context of sensitivity-specificity analysis for methylation detection methods, researchers must navigate a complex landscape of technological platforms, each offering distinct trade-offs in throughput, cost, and genomic coverage. The Illumina Infinium MethylationEPIC BeadChip microarrays have emerged as a dominant platform for epigenome-wide association studies (EWAS), striking a balance between comprehensive coverage and practical implementation for large-scale studies [38] [39]. These arrays utilize a robust bisulfite conversion-based approach followed by hybridization to locus-specific probes, enabling quantitative methylation assessment at single-CpG-site resolution across thousands of samples [40]. As the field advances, understanding the performance characteristics, limitations, and appropriate application contexts for the different iterations of the EPIC platform—particularly in comparison with emerging sequencing-based methods—becomes essential for optimizing research outcomes and ensuring data quality in both basic research and clinical applications [37] [41].

Table 1: Key Specifications of Illumina MethylationEPIC Array Versions

| Parameter | EPIC v1.0 | EPIC v2.0 |

|---|---|---|

| Total Probes | >850,000 | ~930,000 |

| Coverage of RefSeq Genes | >99% | >99% with enhanced regulatory elements |

| Input DNA Requirement | 250 ng | 250 ng |

| Sample Throughput | 8 samples per array | 8 samples per array |

| Compatible Samples | Blood, FFPE tissue | Blood, FFPE tissue (with improved performance) |

| Genome Build | GRCh37/hg19 | GRCh38/hg38 |

| Regulatory Element Coverage | Standard enhancers | Expanded coverage of enhancers, CTCF-binding sites, open chromatin |

| Unique Features | Focus on CpG islands, promoters | ~200,000 new probes, probe replicates, removed poorly performing probes |

Platform Comparison: Technical Specifications and Performance Metrics

Evolution of EPIC Array Content and Design

The Illumina MethylationEPIC platform has undergone significant refinements from version 1.0 to version 2.0, with substantial implications for research applications. EPIC v2.0 retains approximately 77% of the probes from its predecessor while incorporating over 200,000 new probes specifically designed to expand coverage of regulatory elements, including enhancers, super-enhancers, CTCF-binding sites, and open chromatin regions identified through ATAC-Seq and ChIP-seq experiments in primary tumors [38] [40] [39]. This strategic enhancement addresses a critical gap in v1.0's coverage of functional genomic elements beyond traditional promoter regions. Furthermore, EPIC v2.0 has removed approximately 143,000 poorly performing probes from v1.0, approximately 73% of which were potentially influenced by underlying sequence polymorphisms, thereby improving overall data quality and reliability [39]. Another notable advancement in EPIC v2.0 is the implementation of probe replicates (approximately 5,100 probes with 2-10 replicates each), which enable internal quality assessment and technical validation [39] [42].

Comparative Performance Against Sequencing Methods

When evaluating methylation detection platforms, researchers must consider multiple performance dimensions where microarrays and sequencing technologies demonstrate complementary strengths and limitations. Whole-genome bisulfite sequencing (WGBS) provides the most comprehensive coverage with single-base resolution, capturing approximately 80% of all CpG sites across the genome, but requires substantial computational resources, higher costs, and involves DNA degradation due to harsh bisulfite treatment conditions [37] [29]. Enzymatic methyl-sequencing (EM-seq) has emerged as a promising alternative to WGBS, demonstrating high concordance while minimizing DNA damage through enzymatic conversion, but remains cost-prohibitive for large-scale studies [37] [29]. Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing enables direct methylation detection without conversion and provides long-read capabilities for haplotype resolution, but shows lower agreement with established methods and requires high DNA input [37] [29].

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of DNA Methylation Detection Platforms

| Method | Resolution | Coverage | DNA Input | Relative Cost | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EPIC Array | Single CpG site | ~930,000 predefined sites (v2.0) | 250 ng | $$ | High throughput, cost-effective, standardized analysis | Limited to predefined sites, cannot detect novel CpGs |

| WGBS | Single-base | ~80% of genomic CpGs | 1 µg | $$$$ | Comprehensive coverage, detects non-CpG methylation | High cost, DNA degradation, computational intensive |

| EM-seq | Single-base | Comparable to WGBS | Lower than WGBS | $$$$ | Minimal DNA damage, improved library complexity | Higher cost than arrays, bioinformatics complexity |

| ONT | Single-base | Genome-wide, but with coverage biases | ~1 µg (8 kb fragments) | $$$ | Long reads, direct detection, no conversion needed | Lower agreement with established methods, high error rate |

| Targeted BS | Single-base | Custom panels (dozens to hundreds of sites) | 50-100 ng | $ | Cost-effective for validation, high sensitivity for specific targets | Limited scope, panel design required |

Analytical Concordance and Reproducibility

Studies directly comparing methylation profiles across platforms demonstrate strong correlations between EPIC arrays and sequencing-based methods, particularly for well-powered studies. Research examining concordance between Infinium MethylationEPIC arrays and targeted bisulfite sequencing in ovarian cancer tissues and cervical swabs revealed strong sample-wise correlation, especially in tissue samples, though agreement was slightly reduced in cervical swabs likely due to lower DNA quality [43]. This supports the utility of targeted sequencing as a cost-effective validation approach for array-based discoveries. Comparative assessments of multiple genome-wide methylation methods indicate that while EM-seq shows the highest concordance with WGBS, EPIC arrays provide reliable data for the specific CpG sites they target, with each method capturing unique CpG sites and thus offering complementary insights [37]. Importantly, differences between EPIC v1.0 and v2.0, though generally modest, can introduce technical variation in meta-analyses and longitudinal studies, necessitating appropriate batch correction and normalization strategies [38] [39].

Experimental Protocols and Data Generation

Standardized Workflow for EPIC Array Processing

The Infinium MethylationEPIC assay follows a well-established workflow that begins with bisulfite conversion of genomic DNA using kits such as the Zymo Research EZ DNA Methylation Kit, which converts unmethylated cytosines to uracils while leaving methylated cytosines unchanged [29]. The converted DNA is then amplified, fragmented, and hybridized to the BeadChip containing locus-specific probes. After hybridization, the array undergoes single-base extension with fluorescently labeled nucleotides, followed by imaging on iScan or NextSeq 550 Systems [40]. The initial quality assessment typically includes evaluation of detection p-values to identify underperforming samples and probes, with common thresholds excluding samples with average detection p-value > 0.05 across all probes and individual probes with detection p-value > 0.01 in any sample [43] [29]. Data preprocessing generally involves normalization to address technical variation between probe types, with popular approaches including functional normalization [43] and beta-mixture quantile (BMIQ) normalization [42], followed by removal of probes containing common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) or demonstrating cross-reactivity [43].

Analytical Frameworks for Data Processing

Several specialized computational frameworks have been developed to address the unique characteristics of EPIC array data, particularly for the newer v2.0 platform. The MethylCallR package provides a comprehensive analysis pipeline specifically designed to handle EPICv2 features, including duplicated probes and integration with previous array versions through address-based conversion [42]. This package incorporates quality control metrics, outlier detection using Mahalanobis distance, and statistical power estimation to enhance data reliability. For clinical applications, particularly in tumor classification, established pipelines leverage reference databases and supervised machine learning algorithms to generate methylation-based classifications, though these require careful validation to ensure analytical and clinical validity [41]. The minfi and ChAMP packages remain widely used for initial data processing, normalization, and quality control, offering updated functionality for EPICv2 data [29] [42].

Critical Considerations for Platform Selection

Sensitivity, Specificity, and Coverage Trade-offs

The selection of an appropriate methylation profiling platform requires careful consideration of sensitivity, specificity, and coverage requirements specific to the research context. EPIC arrays provide excellent sensitivity for detecting methylation differences at moderate frequencies (typically >5-10% Δβ) across a predefined but biologically relevant subset of the methylome, making them ideal for hypothesis-generating EWAS in large cohorts [37] [43]. Sequencing-based approaches offer superior sensitivity for detecting rare methylation events or heterogeneous patterns and enable discovery of novel methylation sites outside predefined arrays, but at substantially higher cost per sample [37] [29]. In clinical validation studies, targeted bisulfite sequencing panels demonstrate strong concordance with EPIC array data for specific CpG sites, supporting their use as a cost-effective orthogonal validation method for array-based discoveries, particularly when analyzing many samples for a focused set of loci [43].

Technical and Biological Validation Frameworks

Robust technical validation is essential when implementing methylation profiling platforms, particularly for clinical applications. For EPIC arrays, key validation parameters include reproducibility across technical replicates, sensitivity to input DNA quality and quantity, and performance in specific sample types such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissues [40] [41]. The EPICv2 platform demonstrates improved performance with FFPE samples through modified protocols and optional restoration kits, expanding utility for retrospective studies utilizing archival tissues [40]. Biological validation should include confirmation of expected biological patterns, such as detection of known tissue-specific differentially methylated regions, X-chromosome inactivation patterns in female samples, and correlation with established demographic variables like age using epigenetic clocks [39] [42]. When comparing data across EPIC versions, analytical approaches such as ComBat normalization or version-specific modeling can mitigate technical variation introduced by platform differences [38] [39].

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for EPIC Array Methylation Profiling

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Products | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA | Maxwell RSC Tissue DNA Kit, QIAamp DNA Mini Kit | Yield, purity (260/280 ratio), fragment size |

| Bisulfite Conversion Kits | Chemical conversion of unmethylated cytosines | EZ DNA Methylation Kit (Zymo Research), EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (QIAGEN) | Conversion efficiency, DNA degradation, input requirements |

| MethylationEPIC BeadChip | Multiplexed hybridization array | Infinium MethylationEPIC v2.0 BeadChip | Version selection (v1.0 vs v2.0), sample throughput |

| Array Processing Reagents | Amplification, fragmentation, labeling | Infinium HD Methylation Assay | Kit-sample matching, stability, lot-to-lot consistency |

| Quality Control Assays | Assessment of DNA quality pre- and post-conversion | Bioanalyzer High Sensitivity DNA Kit, Qubit fluorometer | DNA quantification, integrity measurement |

| Analysis Software/Packages | Data processing, normalization, statistical analysis | minfi, ChAMP, MethylCallR, GenomeStudio | Compatibility with EPIC version, normalization methods |