Single-Cell RNA-Seq Quality Control: Essential Covariates, Best Practices, and Advanced Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) for single-cell RNA-sequencing data, tailored for researchers and bioinformaticians.

Single-Cell RNA-Seq Quality Control: Essential Covariates, Best Practices, and Advanced Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to quality control (QC) for single-cell RNA-sequencing data, tailored for researchers and bioinformaticians. It covers the foundational theory behind key QC covariates—count depth, genes detected, and mitochondrial fraction—and details best practices for their calculation and application in filtering low-quality cells and technical artifacts like doublets and ambient RNA. The guide further explores advanced strategies for optimizing QC thresholds across diverse datasets and biological contexts, including complex and toxicological studies. Finally, it discusses methods for validating QC effectiveness and comparing automated tools, providing a complete workflow to ensure robust, high-quality data for downstream analysis and reliable biological discovery.

Understanding the Core Covariates: The Foundation of scRNA-seq Quality Control

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling the profiling of gene expression at an unprecedented resolution of individual cells [1] [2]. This technology has proven instrumental in uncovering cellular heterogeneity, identifying rare cell populations, and understanding complex biological processes in both development and disease [3]. However, the data generated from scRNA-seq experiments possess unique characteristics, including an excessive number of zeros (drop-out events) and the potential for technical artifacts to confound biological signals [4]. Therefore, rigorous quality control (QC) is an essential first step in any scRNA-seq analysis workflow to ensure that subsequent interpretations reflect true biology rather than technical noise [4] [1].

The fundamental goal of cell QC is to distinguish high-quality cells from those that are compromised by various issues, including damaged or dying cells, empty droplets, and multiple cells captured together (doublets or multiplets) [3] [5]. Failure to adequately address these quality issues can add significant technical noise that obscures genuine biological signals and potentially leads to erroneous conclusions in downstream analyses [6] [7]. Through carefully calibrated QC procedures, researchers aim to retain the maximum number of high-quality cells while removing those that would otherwise compromise data integrity [4] [5].

The Three Fundamental QC Covariates

Cell quality control in scRNA-seq primarily relies on three key metrics, often called QC covariates: count depth, gene number, and mitochondrial fraction [1] [3] [5]. These covariates provide complementary information about cell quality and must be evaluated jointly rather than in isolation [4] [1].

Count Depth (Total UMIs per Cell)

Definition and Biological Interpretation: Count depth, also referred to as total UMIs per cell or library size, represents the absolute number of unique RNA molecules detected per cell barcode [5] [7]. This metric reflects the efficiency of mRNA capture and sequencing for each individual cell. Extremes in count depth often indicate problematic cells that require careful evaluation.

Quality Implications: Cells with unexpectedly low UMI counts may represent empty droplets, ambient RNA (cell-free mRNA), or severely damaged cells with significant mRNA leakage [1] [5]. Conversely, cells with exceptionally high UMI counts often indicate doublets or multiplets—where two or more cells were captured together in a single droplet or well [1] [3]. These multiplets can artificially suggest intermediate cell states that do not actually exist biologically [7].

Gene Number (Detected Genes per Cell)

Definition and Biological Interpretation: The number of genes detected per cell (sometimes called nFeature) quantifies how many unique genes show positive expression counts in a given cell [4] [5]. This metric serves as an indicator of cellular complexity, reflecting the diversity of the transcriptome captured.

Quality Implications: Low numbers of detected genes typically indicate poor-quality cells, empty droplets, or cells with significant mRNA degradation [3] [5]. On the other hand, unusually high numbers of detected genes often signal doublets, as the combined transcriptomes of multiple cells artificially increase gene diversity [1] [3]. It is crucial to note that biologically less complex cell types or quiescent cell populations may naturally exhibit lower gene counts, highlighting the importance of considering biological context when setting thresholds [1] [5].

Mitochondrial Fraction (Percentage of Mitochondrial Reads)

Definition and Biological Interpretation: The mitochondrial fraction represents the percentage of a cell's total counts that map to mitochondrial genes [4] [5]. This metric is calculated by identifying genes with specific prefixes ("MT-" for human, "mt-" for mouse) and computing their proportional contribution to the total transcriptome [4] [5] [7].

Quality Implications: A high mitochondrial fraction strongly indicates cellular stress, apoptosis, or broken cell membranes [1] [8]. When cytoplasmic mRNA leaks out through compromised membranes, the structurally protected mitochondrial RNA becomes overrepresented in the sequencing library [1] [8]. However, certain cell types involved in respiratory processes may naturally exhibit higher mitochondrial content for legitimate biological reasons [1] [5]. Therefore, this metric must be interpreted with consideration of the expected biology of the sample.

Table 1: Interpretation of QC Covariate Extremes

| QC Covariate | Low Value Indicates | High Value Indicates |

|---|---|---|

| Count Depth | Empty droplet, ambient RNA, severely damaged cell | Doublet/multiplet, larger cell type |

| Gene Number | Poor-quality cell, empty droplet, low-complexity cell type | Doublet/multiplet |

| Mitochondrial Fraction | - | Dying cell, broken membrane, respiratory cell type |

Biological Mechanisms Linking QC Covariates to Cell Quality

The connection between these QC metrics and cell quality is rooted in the underlying biology of cellular stress and the technical aspects of single-cell isolation. When a cell begins to die or undergoes apoptosis, several molecular changes occur that directly impact these QC measurements. The cell membrane becomes compromised, allowing cytoplasmic mRNA—including the majority of the transcriptome—to leak out into the surrounding environment [1] [8]. However, mRNA located within mitochondria remains relatively protected due to the additional membrane barriers of this organelle [8]. Consequently, the relative proportion of mitochondrial RNA increases dramatically, resulting in a high mitochondrial fraction metric [1]. Simultaneously, the loss of cytoplasmic mRNA leads to reduced total UMI counts (count depth) and fewer detected genes (gene number) [1].

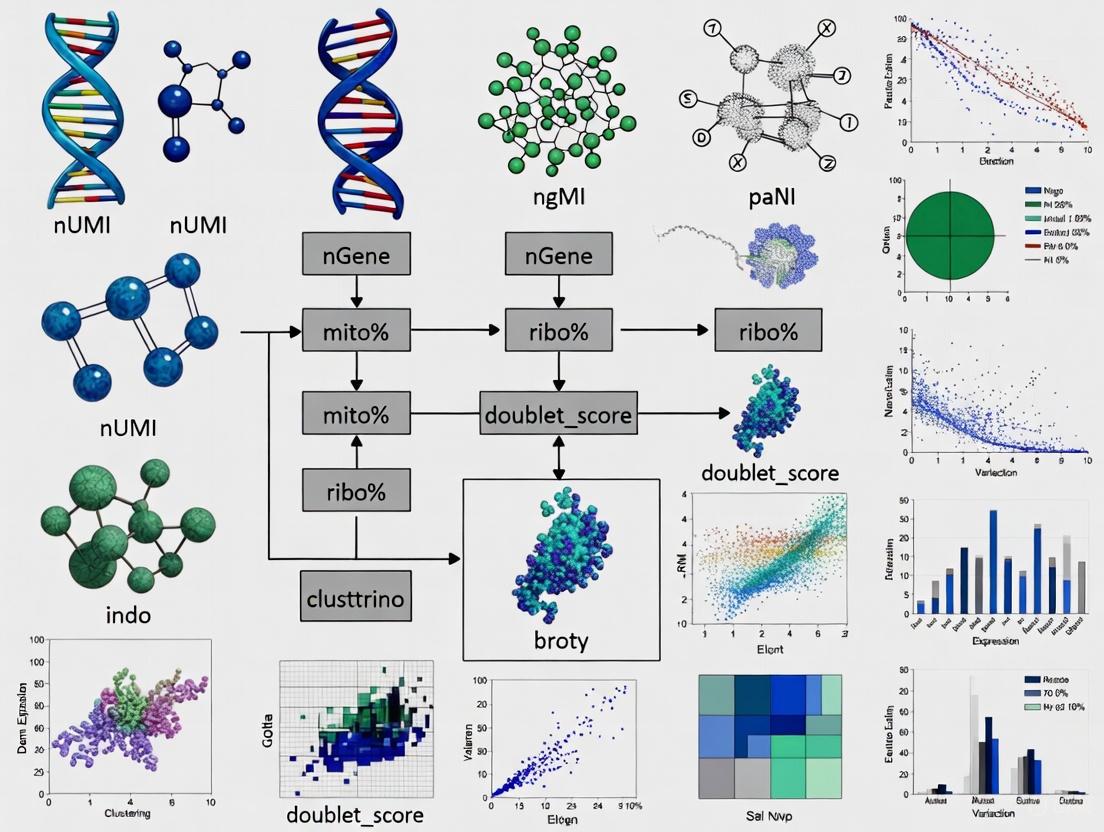

The relationship between technical artifacts and these covariates is equally important to understand. In droplet-based systems, the accidental encapsulation of multiple cells leads to doublets or multiplets, which combine the transcriptomes of distinct cells [1] [8]. This combination artificially inflates both the count depth and the number of detected genes, as molecules from multiple cells are attributed to a single barcode [3]. Empty droplets, which contain ambient RNA released from lysed cells but no intact cell, typically display very low values for both count depth and gene number [1] [5]. The following diagram illustrates how different quality issues manifest in the three QC covariates and the decision process for cell filtering:

Experimental Protocols for QC Implementation

Computational Calculation of QC Metrics

The calculation of QC metrics requires specialized bioinformatics tools that can process single-cell count matrices. Two of the most widely used platforms are Seurat (in R) and Scanpy (in Python), both of which provide built-in functions for computing the essential QC covariates [4] [5] [7].

Scanpy Protocol (Python):

This code identifies mitochondrial, ribosomal, and hemoglobin genes, then computes comprehensive QC metrics including the percentage of mitochondrial counts (pct_counts_mt), total counts per cell (total_counts), and genes detected per cell (n_genes_by_counts) [4].

Seurat Protocol (R):

The Seurat function PercentageFeatureSet() calculates the percentage of counts mapping to mitochondrial genes, using species-specific patterns ("^MT-" for human, "^mt-" for mouse) [5] [7]. The resulting metrics are stored in the object's metadata for subsequent visualization and filtering.

Threshold Selection Strategies

Establishing appropriate thresholds for filtering cells based on QC metrics is a critical step that requires careful consideration. Two primary approaches are commonly used:

Manual Thresholding: Researchers visually inspect the distributions of QC covariates using violin plots, scatter plots, or histograms to identify outlier populations [4] [5]. For example, in the distribution of mitochondrial percentages, one might observe a distinct population of cells with exceptionally high values that clearly separate from the main distribution. Similarly, in the joint visualization of count depth versus gene number, clusters of cells with unusually low or high values may become apparent [4] [7].

Automated Thresholding: For larger datasets or more standardized processing, automated methods like Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) can identify outliers in a data-driven manner [4]. Typically, cells that deviate by more than 3-5 MADs from the median in any key QC metric are flagged as potential low-quality cells [4]. This approach provides consistency and objectivity, particularly when processing multiple datasets.

Table 2: Threshold Guidelines for Different Scenarios

| Scenario | Count Depth | Gene Number | Mitochondrial Fraction |

|---|---|---|---|

| Permissive Filtering | > 500 UMIs [7] | > 300 genes [7] | < 20% [4] |

| PBMC Datasets | Follow 'knee' point in barcode rank plot [9] | Follow distribution 'knee' [9] | < 10% [9] |

| Complex Tissues | Sample-specific thresholds | Sample-specific thresholds | Consider cell-type specific variation |

| Automated (MAD) | 5 MAD from median [4] | 5 MAD from median [4] | 5 MAD from median [4] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful implementation of scRNA-seq QC requires both wet-lab reagents and computational tools. The following table outlines key resources essential for proper quality control:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for scRNA-seq QC

| Category | Item | Function in QC Process |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Cellular Barcodes | Label mRNA from individual cells for multiplexing [1] [8] |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Distinguish biological duplicates from PCR amplification artifacts [1] [8] | |

| Viability Stains (e.g., Propidium Iodide) | Assess cell viability prior to library preparation [3] | |

| Hemocytometer/Automated Cell Counter | Accurately determine cell concentration for optimal loading [7] | |

| Computational Tools | Cell Ranger | Process raw FASTQ files, perform alignment, and generate count matrices [3] [9] |

| Seurat | R-based toolkit for single-cell analysis, including QC metric calculation and visualization [5] [7] | |

| Scanpy | Python-based toolkit for single-cell analysis with comprehensive QC functions [4] | |

| Scater | R package for single-cell analysis with specialized QC capabilities [6] | |

| Doublet Detection Tools (DoubletFinder, Scrublet) | Specifically identify multiplets that may escape standard QC thresholds [1] [5] | |

| SoupX/CellBender | Computational removal of ambient RNA contamination [5] [9] |

Advanced Considerations and Special Cases

While the three core QC covariates provide a solid foundation for quality assessment, several advanced considerations can further refine the QC process. Different biological systems and experimental conditions may require adjustments to standard QC approaches.

Biological Context Dependence: The interpretation of QC metrics must always consider the biological context [5] [7]. For example, cardiomyocytes and other energetically active cells naturally contain high mitochondrial content, making strict mitochondrial thresholds potentially misleading [5] [9]. Similarly, quiescent cell populations such as memory T cells or certain stem cells may exhibit lower transcriptional complexity and count depth without indicating poor quality [1]. Prior knowledge of expected cell types is invaluable for setting appropriate thresholds.

Sample-Type Specific Adaptations: Different sample origins necessitate customized QC approaches. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) typically have well-established expected ranges for QC metrics [9]. In contrast, solid tissues subjected to dissociation protocols may contain more damaged cells, potentially requiring stricter mitochondrial thresholds [3]. Patient-derived organoids and primary tissues often exhibit greater variability in QC metrics compared to well-controlled cell lines [3].

Doublet Detection Beyond Standard Metrics: While high count depth and gene number can suggest doublets, dedicated computational tools such as DoubletFinder, Scrublet, and scDblFinder provide more sophisticated detection by simulating artificial doublets and identifying cells with similar expression profiles [1] [5]. These tools are particularly valuable in heterogeneous samples where multiple cell types increase the likelihood of capturing different cells together.

Ambient RNA Correction: Ambient RNA, released by lysed cells into the solution, can contaminate intact cells and distort expression profiles [5] [9]. Tools like SoupX and CellBender estimate this background contamination and subtract its influence, which is especially important for detecting weakly expressed genes and characterizing rare cell populations [9].

Multi-Sample Considerations: When processing multiple samples, QC should initially be performed on a per-sample basis, as technical variations between samples can affect metric distributions [5]. If samples show similar QC distributions, consistent thresholds can be applied across all samples. If distributions differ significantly, sample-specific thresholds may be necessary to avoid losing valuable biological information [5].

Through careful implementation of these QC procedures, researchers can ensure that their single-cell RNA-seq data provides a reliable foundation for downstream analyses and biological discoveries.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized biological research by enabling transcriptomic profiling at the individual cell level, revealing cellular heterogeneity that bulk sequencing approaches obscure [10]. However, scRNA-seq data possesses unique characteristics that make rigorous quality control (QC) essential for meaningful biological interpretation. The data is characterized by a high number of zeros (dropout events) due to limiting mRNA, and corrections applied during preprocessing may potentially confound technical artifacts with genuine biology [4]. The foundational step in any scRNA-seq analysis is therefore the careful filtering of low-quality cells to ensure downstream results reflect biological truth rather than technical artifacts.

The quality control process begins with a count matrix representing barcodes (potentially representing cells) by transcripts. A critical initial distinction is that not every barcode necessarily corresponds to a viable, intact cell; some may represent empty droplets or multiple cells (doublets) [4]. The central goal of QC is to distinguish and retain high-quality cells for subsequent analysis. This document outlines the biological and technical rationale for key QC metrics, provides structured protocols for their implementation, and visualizes the analytical workflow to guide researchers in making informed decisions.

Core Quality Control Metrics and Their Rationale

Quality control in scRNA-seq primarily revolves around three core covariates, each linked to specific biological or technical phenomena. Filtering decisions are based on thresholds applied to these metrics to remove problematic barcodes.

Table 1: Core QC Metrics and Their Interpretation

| QC Metric | Description | Biological/Technical Rationale | Indication of Low Quality |

|---|---|---|---|

| Count Depth | Total number of counts (UMIs) per barcode. | Reflects the library size and overall RNA content of a cell. | Low counts: Insufficient mRNA capture, broken/dying cell, or empty droplet.Very high counts: Potential multiplet (multiple cells). |

| Genes Detected | Number of genes with positive counts per barcode. | Indicates the complexity of the transcriptome captured. | Low number: Dying cell, poor cDNA synthesis, or small cell type.Very high number: Potential multiplet. |

| Mitochondrial Count Fraction | Percentage of total counts originating from mitochondrial genes. | Elevated levels suggest cell stress or broken cell membranes, as cytoplasmic mRNA leaks out. | High percentage (often >5-15%, context-dependent) [11]. Sign of apoptosis or necrosis. |

It is crucial to consider these three covariates jointly during thresholding. For instance, a cell with a relatively high fraction of mitochondrial counts might be a metabolically active, viable cell (e.g., in respiratory tissues) and should not be automatically filtered out if its total counts and genes detected are also high [4]. Conversely, a cell might appear normal based on one metric but be an outlier in another. The general guidance is to be as permissive as possible initially to avoid filtering out rare or unique cell populations, with the option to re-assess filtering stringency after cell annotation [4].

Quantitative Thresholds and Experimental Protocols

Establishing Filtering Thresholds

Thresholds for QC metrics can be established either manually by inspecting the distributions of the covariates or automatically using robust statistical methods, especially as dataset sizes grow.

Table 2: Quantitative Guidelines for QC Filtering

| Factor | Typical Range/Consideration | Notes and Sources | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondrial % Threshold | 5% to 15% [11]. | Highly dependent on species, sample type, and experiment. Human samples often have a higher baseline than mouse; metabolically active tissues (e.g., kidney) may show robust expression. | ||

| Multiplet Rate (10x Genomics) | ~5.4% for 7,000 cells; increases with loaded cells [11]. | A technical artifact of the platform. Tools like DoubletFinder and Scrublet are used for detection. | ||

| Cell Viability for Input | >85% recommended [12]. | Critical for generating a high-quality single-cell suspension and reducing ambient RNA. | ||

| Automatic Thresholding (MAD) | 5 Median Absolute Deviations (MADs) [4]. | A robust, data-driven method for identifying outliers in large datasets. Formula: (MAD = median( | X_i - median(X) | )) |

Step-by-Step Protocol: Calculating and Filtering QC Metrics

This protocol uses the Python-based Scanpy library, a standard tool for scRNA-seq analysis.

Protocol: Basic QC and Filtering with Scanpy

Environment Setup and Data Loading

Annotate Gene Groups Annotate genes for calculating quality metrics. The prefix for mitochondrial genes is species-specific (

'MT-'for human,'mt-'for mouse).Calculate QC Metrics Use

sc.pp.calculate_qc_metricsto compute key metrics, which are added to theadata.obsDataFrame.This calculates, for each barcode:

n_genes_by_counts: Number of genes with positive counts.total_counts: Total number of UMIs.pct_counts_mt: Percentage of total counts that are mitochondrial.

Visualize QC Metrics Generate plots to inspect the distributions and set thresholds.

Apply Filters Filter barcodes based on chosen thresholds. This example uses manual thresholds.

For automatic filtering using the MAD (5 MADs is a common, permissive threshold):

Addressing Technical Artifacts Beyond Basic Metrics

Doublet Detection and Removal

A doublet occurs when two or more cells are captured within a single droplet or well, leading to a hybrid transcriptomic profile that can be misinterpreted as a novel or transitional cell state [11]. The multiplet rate is platform-dependent and increases with the number of loaded cells.

Recommended Tools and Strategy:

- Tools: DoubletFinder, Scrublet, doubletCells [11].

- Performance: Tools show substantial variation across datasets. DoubletFinder has been noted to outperform others in some benchmarks for downstream tasks like differential expression and clustering [11].

- Protocol: It is recommended to use a combination of automated tools and manual inspection. Cells that co-express well-established markers of distinct cell types should be carefully scrutinized to decide if they represent genuine biological states or technical doublets.

Ambient RNA Correction

Ambient RNA consists of transcripts released from dead or apoptotic cells into the solution, which can then be encapsulated in droplets along with intact cells, contaminating the gene expression profile [11]. This can lead to incorrect cell-type annotation.

Recommended Tools and Strategy:

- SoupX: Does not require precise pre-annotation but needs user input regarding marker genes expected to be absent in certain cell types. Reported to perform better with single-nucleus data (snRNA-seq) than single-cell [11].

- CellBender: Suited for cleaning noisy datasets and provides accurate estimation of background noise [11].

- Protocol: Removal of genes associated with stress signatures or dissociation should be approached cautiously, as their expression can sometimes reflect genuine biological responses [11].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for scRNA-seq QC

| Item | Function / Role in QC |

|---|---|

| 10x Genomics Chromium Controller | A droplet-based platform for high-throughput single-cell partitioning. Its GEM technology uniquely barcodes cellular mRNA [12]. |

| Barcoded Gel Beads | Contain millions of oligonucleotides with cell barcode, UMI, and poly(dT) sequence for mRNA capture and tagging within each GEM [12]. |

| Viability Stain (e.g., DAPI, Propidium Iodide) | Used to assess cell viability (>85% is recommended) prior to loading on the platform, directly impacting data quality by reducing ambient RNA [12]. |

| Cell Ranger (10x Genomics) | Standard software suite for processing raw sequencing data (BCL files) from 10x experiments. It performs alignment, filtering, barcode counting, and UMI counting to generate a gene-cell matrix [10]. |

| Scanpy / Seurat | Open-source computational toolkits (Python/R) that provide the statistical and visualization functions necessary for calculating QC metrics, generating plots, and executing filtering steps [4]. |

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in the scRNA-seq quality control process, integrating the concepts and protocols detailed above.

Diagram 1: scRNA-seq Quality Control Workflow. This diagram outlines the key steps in a standard QC pipeline, from initial data to a filtered dataset ready for downstream analysis.

A rigorous and well-understood quality control process is the non-negotiable foundation of any robust scRNA-seq study. By systematically evaluating metrics linked to cell viability and technical artifacts—count depth, genes detected, and mitochondrial fraction—researchers can make informed decisions to preserve biological signal while removing technical noise. The protocols and guidelines provided here, emphasizing the joint consideration of covariates and the use of both manual and automated thresholding methods, offer a pathway to generating high-quality data. This ensures that subsequent analyses, from clustering to trajectory inference, are built upon a reliable representation of true cellular heterogeneity, ultimately strengthening the biological conclusions drawn from single-cell experiments.

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to study cellular heterogeneity and gene expression patterns at unprecedented resolution. However, the accuracy of these biological insights critically depends on effective quality control (QC) to distinguish high-quality cells from technical artifacts. Droplet-based scRNA-seq protocols, which enable massive parallel sequencing of thousands of cells, inevitably generate certain populations that can compromise downstream analysis if not properly identified and removed. These include dying cells with compromised membranes, empty droplets containing only ambient RNA, and doublets (or multiplets) where two or more cells are captured within a single droplet [4] [13]. Each of these artifact types exhibits distinct molecular profiles that can be leveraged for their identification. Dying cells typically show elevated mitochondrial transcript fractions and reduced RNA complexity, empty droplets display limited transcript diversity that matches the ambient RNA profile, and doublets exhibit aberrantly high gene counts and chimeric expression patterns representing multiple cell types [1] [14]. This protocol outlines comprehensive methods for identifying these low-quality cells using QC covariates within the broader context of single-cell RNA-seq quality control frameworks, providing researchers with standardized approaches to ensure data integrity before proceeding to biological interpretation.

Characteristic Profiles of Low-Quality Cells

Biological and Technical Origins

Understanding the biological and technical origins of low-quality cells is essential for their proper identification. During tissue dissociation, cells undergo mechanical and enzymatic stress that can compromise membrane integrity, leading to the release of cytoplasmic RNA into the suspension medium. This released RNA constitutes the "ambient" pool that can be co-encapsated with intact cells or independently into empty droplets [15] [13]. Meanwhile, the stochastic nature of droplet encapsulation means that some droplets will contain multiple cells despite optimization efforts, with doublet rates increasing proportionally with the number of cells loaded [16] [17]. Dying cells with compromised membranes allow cytoplasmic mRNA to leak out while retaining mitochondrial mRNAs, resulting in characteristic profiles with high mitochondrial fractions and low detected genes [4] [1]. Empty droplets contain only ambient RNA derived from the collective pool of transcripts from all cells in the suspension, producing a background expression profile that differs markedly from any genuine cell [15]. Doublets create artificial expression profiles that appear as intermediate cell states or novel cell populations, potentially leading to misinterpretation of cellular differentiation trajectories or false discovery of hybrid cell types [16] [18].

Quantitative Metrics for Identification

The identification of low-quality cells relies on quantitative metrics derived from the expression matrix. The table below summarizes the characteristic profiles of each artifact type:

Table 1: Characteristic QC Profiles of Low-Quality Cells

| Cell Type | Total UMI Counts | Genes Detected | Mitochondrial Fraction | Other Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viable Cell | Moderate to high | Moderate to high | Low to moderate (cell-type dependent) | Balanced gene expression; fits expected cell type profile |

| Dying Cell | Low | Low | High (>20% often used as threshold) [4] [14] | Reduced complexity (genes per UMI); stress response genes可能upregulated |

| Empty Droplet | Very low (<100 UMIs) but non-zero [15] | Very low | Variable, matches ambient profile | Expression profile matches estimated ambient RNA; insignificant p-value in EmptyDrops test |

| Doublet | High (often extreme outliers) [14] | High (often extreme outliers) | Variable, may be intermediate between source cell types | Co-expression of mutually exclusive markers; intermediate position in reduced dimension space |

These quantitative metrics provide the foundation for computational detection methods. For dying cells, the combination of low total counts, low gene detection, and high mitochondrial fraction is particularly indicative of poor quality [4] [1]. Empty droplets are distinguished by their similarity to the ambient RNA profile despite having non-zero counts [15]. Doublets are identified through their aberrantly high molecular counts and gene detection, plus the co-expression of marker genes that are normally mutually exclusive in genuine single cells [16] [17].

Table 2: Typical Threshold Ranges for QC Metrics

| QC Metric | Typical Threshold Range | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Total UMI Counts | 500-50,000 (highly cell-type dependent) [7] | Lower threshold removes empty droplets; upper threshold removes doublets |

| Genes Detected | 300-6,000 (highly cell-type dependent) [14] | Neutrophils naturally low; activated cells naturally high |

| Mitochondrial Fraction | 5-20% (tissue and cell type dependent) [4] [14] | Cardiomyocytes naturally high; some protocols show higher baseline |

| Doublet Score | Variable by method and dataset [17] | Typically set to achieve expected doublet rate (0.4-8% depending on cells loaded) |

Experimental Protocols for Cell Quality Assessment

Sample Preparation and Data Generation

The foundation of effective quality control begins with proper experimental design and sample preparation. For droplet-based single-cell RNA sequencing using 10X Genomics Chromium systems, critical attention must be paid to cell viability, concentration accuracy, and sample multiplexing. Cell viability should exceed 80% to minimize dying cells and reduce ambient RNA [1]. Accurate cell concentration quantification using a hemocytometer or automated cell counter is essential, as inaccuracies here directly impact doublet rates [7]. For studies involving multiple samples, cell hashing with oligonucleotide-conjugated antibodies enables sample multiplexing and provides a ground truth method for doublet identification through the detection of multiple hashtags in single droplets [18]. The library preparation should follow manufacturer protocols with particular attention to the incorporation of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to correct for amplification bias. For the DOGMA-seq protocol mentioned in the search results, which simultaneously measures transcriptome, cell surface protein, and chromatin accessibility, the multi-modal nature of the data can enhance doublet detection through the COMPOSITE method [18]. Sequencing depth should be sufficient to detect lowly-expressed genes while avoiding excessive spending on sequencing saturation; typically 20,000-50,000 reads per cell provides good gene detection for most applications.

Computational Detection of Empty Droplets

The EmptyDrops algorithm provides a robust statistical framework for distinguishing cell-containing droplets from empty droplets based on deviations from the ambient RNA profile [15] [13]. The method operates through the following workflow:

Estimate Ambient RNA Profile: All barcodes with total UMI counts ≤100 are considered to represent empty droplets. The counts for each gene across these barcodes are summed to create the ambient profile vector A = (A1, A2, ..., AN) for all N genes [15].

Apply Good-Turing Algorithm: The Good-Turing algorithm is applied to A to obtain the posterior expectation ṗg of the proportion of counts assigned to each gene g, ensuring genes with zero counts in the ambient pool have non-zero proportions [15].

Calculate Likelihood of Observed Profiles: For each barcode with total count tb, the likelihood Lb of observing its count profile is computed using a Dirichlet-multinomial distribution with probabilities ṗg and scaling factor α estimated from the ambient profile [15].

Compute Significance via Monte Carlo: For each barcode, p-values are computed using Monte Carlo simulations (typically 10,000 iterations) by comparing Lb to likelihoods L′bi of count vectors simulated from the null Dirichlet-multinomial distribution [15] [13].

Combine with Knee Point Detection: Barcodes with significantly different profiles from the ambient (FDR < 0.1%) are retained as cells, along with any barcodes above the "knee point" in the total count distribution regardless of significance [15].

The following DOT language script visualizes the EmptyDrops workflow:

Identification of Dying Cells Through QC Metrics

The protocol for identifying dying cells employs calculated QC metrics to detect cells with compromised membrane integrity:

Calculate QC Metrics: Using the scanpy or Seurat toolkit, compute for each barcode:

- Total UMI counts (library size)

- Number of genes with positive counts

- Mitochondrial fraction: Percentage of counts mapping to mitochondrial genes [4] [1]

- Ribosomal fraction: Percentage of counts mapping to ribosomal genes

- Hemoglobin fraction (for blood cells): Percentage of counts mapping to hemoglobin genes [4]

- Genes per UMI ratio (complexity measure) [7]

Define Mitochondrial Genes: Identify mitochondrial genes by prefix:

- Human: "MT-"

- Mouse: "mt-" [4]

- Verify prefix appropriateness for your species and annotation

Set Thresholds Using MAD: For systematic thresholding without manual inspection:

- Compute median absolute deviation (MAD) for each QC metric: MAD = median(|Xi - median(X)|)

- Mark cells as outliers if they are >5 MADs from the median for any key metric [4]

- Apply multivariate consideration to avoid removing biologically distinct cell types

Visual Inspection and Adjustment: Generate diagnostic plots:

Iterative Threshold Refinement:

Doublet Detection Methods

Doublet detection employs both cluster-based and simulation-based approaches to identify droplets containing multiple cells:

Cluster-Based Detection with findDoubletClusters

The findDoubletClusters function from the scDblFinder package identifies clusters with expression profiles lying between two other clusters [16]:

Cluster Cells: Perform standard clustering on the expression data using graph-based or k-means approaches

Test Cluster Triplets: For each potential "query" cluster and pair of "source" clusters:

- Compute the number of genes (num.de) that are differentially expressed in the same direction in the query compared to both sources

- Under the null hypothesis that the query consists of doublets from the two sources, num.de should be small

- Calculate library size ratios: median library size in each source divided by median in query (should be <1 for true doublets) [16]

Rank Suspicious Clusters: Rank clusters by num.de, with the lowest values representing the most likely doublet clusters

Examine Marker Expression: Validate potential doublet clusters by checking for co-expression of mutually exclusive marker genes from different cell types [16]

Simulation-Based Detection with computeDoubletDensity

The computeDoubletDensity function from scDblFinder identifies doublets through in silico simulation [16]:

Simulate Doublets: Generate thousands of artificial doublets by randomly adding together the expression profiles of two randomly chosen real cells

Compute Local Densities:

- For each real cell, compute the density of simulated doublets in its neighborhood

- For each real cell, compute the density of other real cells in its neighborhood

Calculate Doublet Score: For each cell, compute the ratio between the simulated doublet density and the real cell density as a doublet score

Classify Doublets: Identify large outliers in the doublet score distribution as likely doublets, typically focusing on cells with scores >2 standard deviations above the mean

Integrated Detection with Scrublet and DoubletFinder

For comprehensive doublet detection, multiple methods should be employed:

Scrublet Method:

- Simulate doublets by averaging random cell pairs

- Embed cells and simulated doublets in lower-dimensional space

- Train a k-nearest neighbor classifier to identify real cells resembling simulated doublets [17]

DoubletFinder Method:

Multiomics Approach with COMPOSITE:

- For multiomics data (e.g., RNA+ATAC+ADT), leverage stable features that show minimal variability across cell types but differ between singlets and multiplets

- Model each modality with compound Poisson distributions (Gamma for RNA/ATAC, Gaussian for ADT)

- Combine likelihoods across modalities with modality-specific weights [18]

The following DOT language script illustrates the multi-modality doublet detection approach:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful identification of low-quality cells in single-cell RNA-seq experiments requires both wet-lab reagents and computational tools. The table below summarizes key solutions used throughout the protocols described in this application note:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for Quality Control

| Category | Item | Function/Application | Examples/Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Cell Hashing Antibodies | Sample multiplexing and experimental doublet detection [18] | BioLegend TotalSeq antibodies; allows pooling of multiple samples before encapsulation |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Viability Dyes | Assessment of cell integrity before library preparation | Propidium iodide, DAPI, or flow cytometry-compatible viability markers |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | Nuclei Isolation Kits | For single-nucleus RNA-seq when cell integrity is compromised | 10X Genomics Nuclei Isolation Kits; suitable for frozen samples |

| Wet-Lab Reagents | RNase Inhibitors | Prevention of RNA degradation during processing | Protects RNA integrity throughout dissociation and library prep |

| Computational Tools | EmptyDrops | Distinguishes cells from empty droplets [15] [13] | Part of DropletUtils (Bioconductor); superior to fixed UMI thresholds |

| Computational Tools | ScDblFinder | Doublet detection via cluster-based and simulation methods [16] | Includes findDoubletClusters and computeDoubletDensity functions |

| Computational Tools | DoubletFinder | High-accuracy doublet detection via artificial nearest neighbors [17] [19] | Benchmark studies show top performance in detection accuracy |

| Computational Tools | Scrublet | Doublet detection in Python workflows [17] | Popular Python implementation of simulation-based approach |

| Computational Tools | COMPOSITE | Multiplet detection in single-cell multiomics data [18] | Specifically designed for RNA+ATAC+ADT multiome data |

| Computational Tools | SoupX | Removal of ambient RNA contamination from count matrices [13] | Corrects for background expression signals |

| Analysis Platforms | Seurat | Comprehensive scRNA-seq analysis platform [7] | R-based; includes QC visualization and filtering functions |

| Analysis Platforms | Scanpy | Python-based single-cell analysis suite [4] | Includes QC metric calculation and visualization |

The accurate identification of low-quality cells—dying cells, empty droplets, and doublets—is a critical prerequisite for robust single-cell RNA-seq analysis. This protocol has outlined characteristic profiles and detection methods for each artifact type, emphasizing their distinct molecular signatures. The implementation of these QC procedures should follow a sequential approach: first, identify and remove empty droplets using EmptyDrops; second, filter dying cells based on joint consideration of mitochondrial fraction, detected genes, and total counts; third, detect doublets using complementary computational methods; and finally, iteratively reassess filtering decisions after initial clustering. Throughout this process, researchers should maintain awareness of biological context, as certain cell types may naturally exhibit QC metric extremes that should be preserved rather than filtered. The integration of these QC procedures into standardized workflows will enhance the reliability and reproducibility of single-cell RNA-seq studies, ensuring that biological conclusions are grounded in high-quality data.

In single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis, quality control (QC) is a critical first step to ensure the reliability and interpretability of the data. While standard QC focuses on metrics like the number of detected genes and mitochondrial RNA proportion, this article delves into three advanced, yet crucial, QC covariates: ribosomal RNA, hemoglobin RNA, and spike-in RNA. These metrics are not merely indicators of cell health; they provide deep insights into technical artifacts, biological heterogeneity, and the very accuracy of transcript counting [11] [20] [21]. Proper management of these factors is essential for transforming raw sequencing data into robust biological discoveries, particularly in complex tissues and disease models.

Quantitative Data in Quality Control

The following tables summarize key quantitative thresholds and impacts associated with these QC covariates.

Table 1: Summary of Key QC Covariates: Functions and Filtering Strategies

| QC Covariate | Biological/Technical Role | Typical Filtering Approach | Notes and Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) | Core component of the protein synthesis machinery; highly abundant. | Often filtered out bioinformatically; high proportions can mask biological signal. | High expression may indicate a specific metabolic state; filtering can sometimes be omitted for certain biological questions [11]. |

| Hemoglobin RNA (Hgb) | Oxygen transport in red blood cells (RBCs) and chondrocytes. | Critical to remove from non-RBC samples (e.g., PBMCs); can be depleted via kit or bioinformatically. | Bioinformatic removal drastically reduces usable library size (median ~57%) and degrades signal, making kit-based depletion preferred for blood samples [20]. |

| Spike-in RNA | Exogenous controls added in known quantities for normalization. | Used to calculate scaling factors; not for filtering cells. | Provides a ground truth for normalization, especially when biological assumptions of stable gene expression are violated [22] [21]. |

Table 2: Impact of Globin Depletion Methods on RNA-seq Data (Based on [20])

| Metric | Kit-Based Depletion | Bioinformatic Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Median % of reads mapping to globin genes | 0.32% | 57.24% |

| Reduction in usable library size post-bioinformatic depletion | ~0.37% | ~57% |

| Detection of non-coding RNAs (e.g., lncRNA, miRNA) | Significantly higher proportions | Underrepresented |

| Sensitivity in detecting disease-relevant gene expression changes | High | Reduced |

Experimental Protocols and Applications

Protocol: Assessing and Filtering Ribosomal RNA

Background: Ribosomal proteins (e.g., RPS, RPL genes) are among the most highly expressed genes. While their overabundance can introduce unwanted technical variation in clustering, they can also reflect genuine biological states and should not be automatically filtered without consideration [11].

Methodology:

- Gene Identification: Identify ribosomal genes in your feature list. This is typically done by searching for gene names starting with "RPS" or "RPL" [4].

- QC Metric Calculation: Calculate the percentage of ribosomal counts per cell.

- Visualization and Decision: Plot the percentage of ribosomal RNA against other QC metrics, such as the number of detected genes. There is no universal threshold for filtering ribosomal RNA. Decisions should be based on the dataset's specific characteristics and biological context. High ribosomal proportion coupled with low gene detection may indicate low-quality libraries, but otherwise, it may be a biological feature [4] [23].

Protocol: Controlling for Hemoglobin RNA Effects

Background: In blood samples, hemoglobin transcripts can constitute over 70% of the mRNA population, severely limiting sequencing depth for other transcripts [20]. Hemoglobin expression has also been observed in non-erythroid cells, such as chondrocytes, where it may play a role in oxygen storage [24].

Methodology:

- Proactive Depletion (Best Practice): For whole blood RNA-seq, use globin kit depletion (e.g., RNase H-based or probe hybridization methods) prior to library preparation. This physically removes Hgb transcripts, preserving sequencing depth and the diversity of other gene biotypes [20].

- Bioinformatic Removal & Filtering: If kit depletion was not performed, Hgb reads must be removed bioinformatically.

- Identification: Define hemoglobin genes (e.g., HBA1, HBA2, HBB).

- Filtering Cells: In non-erythroid tissues (e.g., PBMCs), filter out cells that express hemoglobin genes above a baseline level, as this likely indicates ambient RNA contamination [4].

- Bioinformatic Depletion: Remove reads aligning to Hgb genes from the count matrix. Note: This leads to a significant reduction in usable library size and lower sensitivity [20].

- Biological Investigation: In studies involving chondrocytes or similar cells, hemoglobin expression should be investigated as a biological signal rather than filtered as a contaminant. Analysis can include comparing HBB high- and low-expression groups to identify associated pathways [24].

Protocol: Utilizing Spike-in RNAs for Normalization

Background: Spike-in RNAs are synthetic transcripts added in equal quantities to each cell's lysate. They serve as an external standard to control for technical variation in capture efficiency and amplification, enabling true quantitative normalization [22] [21].

Methodology:

- Selection and Addition: Use a commercially available spike-in kit (e.g., ERCC ExFold RNA Spike-In Mixes). Add a fixed volume of spike-in solution to the lysis buffer of each cell [22].

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Process spike-in RNAs alongside endogenous mRNAs through reverse transcription, library preparation, and sequencing.

- Normalization: Scale the counts for each cell so that the coverage of the spike-in transcripts is constant across all cells. This corrects for cell-specific biases.

- Principle: The central assumption is that the same amount of spike-in RNA is added to each cell and that it behaves similarly to endogenous mRNA [22].

- Validation: Studies using mixture experiments with two distinct spike-in sets have shown that the variance in added spike-in volume is negligible, confirming the reliability of this approach for scaling normalization [22].

- Advanced QC with Molecular Spikes: For ultimate accuracy, use "molecular spikes," which are spike-ins containing built-in Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs). These allow for direct benchmarking of a protocol's RNA counting accuracy and evaluation of computational UMI error-correction methods [21].

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making workflow for managing these three key QC covariates in a scRNA-seq experiment.

Diagram 1: QC Covariate Assessment Workflow. This chart outlines the decision process for handling ribosomal, hemoglobin, and spike-in RNA, guiding whether to treat them as biological signal, technical noise, or normalization factors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Advanced QC

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in RNA Mixes (e.g., ERCC, SIRV) | Exogenous RNA controls for normalization and quantification. | Added to cell lysates to control for technical variation in scRNA-seq; allows for accurate scaling normalization [22] [21]. |

| Globin Depletion Kits | Proactively remove hemoglobin mRNA during library prep. | Used for RNA-seq from whole blood to prevent Hgb RNA from dominating the library, preserving sequencing depth for other transcripts [20]. |

| Molecular Spikes (spUMI spikes) | Spike-in RNAs with internal UMIs to benchmark counting accuracy. | Diagnose and correct for UMI counting inflation in scRNA-seq protocols; provides a ground truth for evaluating pipelines [21]. |

| Reference Cells (e.g., 32D, Jurkat) | Standardized cells spiked into samples as internal controls. | Identify sample-specific contamination (e.g., cell-free RNA) in droplet-based scRNA-seq; enables robust contamination correction [25]. |

| Bioinformatic Tools (e.g., SoupX, CellBender) | Computational removal of ambient RNA contamination. | Clean up noisy datasets by estimating and subtracting background RNA counts that have leaked into droplets [11]. |

Quality control (QC) is a critical first step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis, serving to filter out low-quality cells and technical artifacts so that downstream analyses reflect true biological variation. This protocol details the application of three essential visualization techniques—knee plots, histograms (or density plots), and violin plots—for the exploration and assessment of key QC covariates. We provide a step-by-step guide for generating these plots using common analysis frameworks, interpreting their patterns to make informed filtering decisions and integrating these metrics into a standardized QC workflow. Proper utilization of these visualizations ensures the retention of high-quality cells, forming a reliable foundation for all subsequent biological interpretations in drug development and basic research.

In single-cell RNA-seq research, the initial data matrix contains not only high-quality cells but also empty droplets, low-viability cells, and multiplets [26]. Visualizing quality control metrics allows researchers to distinguish these technical artifacts from biological signals. This document frames the application of knee plots, histograms, and violin plots within the broader thesis that systematic assessment of QC covariates—including UMI counts, genes detected per cell, and mitochondrial gene expression—is a non-negotiable prerequisite for robust scRNA-seq analysis [27] [28]. For researchers and drug development professionals, this process is crucial for identifying rare cell populations, understanding tumor microenvironments, and accurately characterizing cellular response to therapeutic compounds without the confounding influence of poor-quality data.

Key QC Metrics and Their Biological Significance

The following table summarizes the primary QC metrics visualized in this protocol, their biological or technical interpretations, and common filtering thresholds.

Table 1: Essential QC Metrics for Single-Cell RNA-Seq Analysis

| QC Metric | Technical/Biological Meaning | Indication of Low Quality | Common Filtering Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|

| UMI Counts per Cell | Total number of uniquely barcoded mRNA molecules detected [27]. | Too low: Empty droplet / poorly captured cell. Too high: Multiplets (doublet/triplet) [28] [7]. | Often > 500-1000 [7]; No absolute standard, depends on experiment [27]. |

| Genes Detected per Cell | Number of unique genes expressed in a cell (complexity) [27]. | Too low: Empty droplet or dying cell. Too high: Multiplets or technical artifact [27]. | Typically > 200-500; often filter cells with ≤ 100 or ≥ 6000 genes [27]. |

| Mitochondrial Gene Ratio | Percentage of transcripts originating from mitochondrial genome [27]. | High values indicate cell stress, apoptosis, or broken cytoplasm [27] [7]. | Often 5-20%; a common threshold is ≥10% [27]. Varies by cell type and tissue. |

| Genes per UMI (Novelty) | Measure of library complexity (number of genes detected per UMI) [7]. | Low values indicate a few highly expressed genes dominate the library, potentially from low-complexity cells or ambient RNA. | No fixed threshold; used to identify less complex cells that are outliers in the distribution. |

Visualizing QC Metric Distributions: Protocols and Interpretation

Knee Plots for Empty Droplet Detection

Knee plots are used primarily in droplet-based scRNA-seq protocols to distinguish barcodes associated with true cells from those associated with empty droplets containing only ambient RNA [29] [26].

Experimental Protocol

- Data Input: Use the raw, unfiltered count matrix (the "Droplet matrix") containing every barcode from the sequencing run, including those from empty droplets [26].

- Calculation: Rank all barcodes from highest to lowest based on their total UMI count [29].

- Plotting: Create a log-log scatterplot with the barcode rank on the x-axis and the corresponding UMI count on the y-axis [29].

- Threshold Identification: Visually identify the inflection point or "knee" in the curve, where the transition from high-quality cells to empty droplets occurs. Barcodes to the left of the knee represent candidate cells.

Interpretation Guide

The resulting plot shows a steeply declining curve. The leftmost section of the plot, with the highest UMI counts, represents high-quality cells. The prominent "knee" indicates the point where barcodes transition from containing true cells to those containing only background RNA. The long tail to the right consists of empty droplets or low-quality barcodes with minimal UMI counts [29]. The knee point is often used to set a UMI count threshold for initial cell selection.

Histograms and Density Plots for Metric Distribution Assessment

Histograms and density plots provide a global view of the distribution of a specific QC metric (e.g., UMI counts, genes per cell) across all barcodes initially identified as cells [7].

Experimental Protocol

- Data Input: Use the count matrix after empty droplet filtration (the "Cell" matrix).

- Metric Calculation: Compute the desired QC metric (e.g.,

nCount_RNAfor UMIs,nFeature_RNAfor genes) for every cell barcode. - Plotting:

- For a histogram, bin the cells based on the metric value and plot the frequency of cells in each bin.

- For a density plot, use a kernel function to estimate the continuous probability density of the metric, often plotted with a logarithmic x-axis [7].

- Threshold Lines: Add vertical lines to indicate proposed filtering thresholds.

Interpretation Guide

An ideal, high-quality dataset will show a single, large peak representing the majority of intact cells [7]. A bimodal distribution or a large shoulder to the left of the main peak can indicate the presence of a subpopulation of low-quality or dying cells. A long tail to the right with very high values may suggest the presence of doublets or multiplets. These plots allow researchers to set minimum and maximum thresholds to filter out the low and high outliers.

Violin Plots for Comparative QC Across Samples

Violin plots are indispensable for visualizing the distribution of multiple QC metrics simultaneously and for comparing these distributions across different samples or experimental conditions [27]. They combine the summary statistics of a box plot with the detailed distribution shape of a density plot.

Experimental Protocol

- Data Input: Use the Cell matrix with sample metadata incorporated.

- Data Structuring: Organize the data so that each cell has its QC metrics and a sample identifier (e.g., "ctrl" or "stim").

- Plotting: For a given metric (e.g., mitochondrial ratio), create a violin plot where each "violin" represents one sample. The width of the violin shows the density of cells at that value, and an overlaid box plot often indicates the median and quartiles [27].

- Multi-Metric View: Create a panel of violin plots to inspect all key metrics (UMIs, genes, mitochondrial ratio) at a glance.

Interpretation Guide

The width of the violin at a given value indicates the proportion of cells at that value. A wide section in the high mitochondrial region for a specific sample suggests widespread cell stress in that sample. Shifts in the median (shown by the box plot inside the violin) between conditions for UMI or gene counts can indicate systematic technical differences (batch effects) that may need correction. These plots are critical for identifying sample-specific QC issues that might be masked by looking only at aggregate data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogues essential software tools and packages that implement the QC visualization protocols described herein.

Table 2: Essential Tools for scRNA-seq QC Visualization

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application in QC Visualization |

|---|---|---|

| Seurat [7] [30] | A comprehensive R package for single-cell genomics. | Directly calculates and visualizes QC metrics (violin plots, scatter plots) and facilitates filtering. |

| DropletUtils [26] | An R/Bioconductor package for droplet-based data. | Contains the barcodeRanks function for generating knee plots and empty droplet detection. |

| SingleCellTK (SCTK-QC) [26] | A comprehensive R package and pipeline for scRNA-seq QC. | Streamlines the generation of knee plots, violin plots, and other QC metrics from multiple algorithms into a standardized workflow and HTML report. |

| ScRDAVis [31] | An interactive R Shiny application. | Provides a user-friendly graphical interface for performing QC and generating standard plots without programming. |

| Loupe Browser (10X Genomics) [31] [32] | A commercial desktop visualization software. | Allows interactive exploration of knee plots, UMAPs, and gene expression for data generated on the 10X platform. |

From Theory to Practice: A Step-by-Step Guide to Implementing QC

Quality control (QC) constitutes a critical first step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) data analysis. The data generated by scRNA-seq technologies possess two fundamental characteristics: they are inherently dropout-prone, containing an excessive number of zeros due to limiting mRNA, and they face potential confounding with biology, where technical artifacts can mimic or obscure true biological signals [4]. Effective QC procedures aim to filter out low-quality cells while preserving biological heterogeneity, thereby ensuring that downstream analyses such as clustering, differential expression, and trajectory inference yield valid and interpretable results. This protocol focuses on practical implementation of QC metrics calculation using two predominant analysis ecosystems: Scanpy (Python-based) and Seurat (R-based) [33].

The core QC covariates routinely examined include: (1) the number of counts per barcode (count depth), (2) the number of genes detected per barcode, and (3) the fraction of counts originating from mitochondrial genes [4]. Cells exhibiting a low number of detected genes, low count depth, and high mitochondrial fraction often indicate compromised cellular integrity—where broken membranes allow cytoplasmic mRNA to leak out, leaving only the larger mitochondrial mRNA molecules [34]. The following sections provide detailed methodologies and code snippets for calculating and interpreting these essential QC metrics.

A standardized QC workflow for scRNA-seq data encompasses sequential steps from raw data input through to filtered data output. The logical flow of this process is visualized in the following diagram, which outlines the key decision points and analytical stages.

Figure 1: Single-Cell RNA-Seq Quality Control Workflow. This diagram illustrates the standard workflow for scRNA-seq quality control, from initial data input through metric calculation, visualization, and filtering.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Successful execution of scRNA-seq quality control requires both experimental reagents and computational resources. The following table catalogues the essential components of the single-cell researcher's toolkit.

Table 1: Research Reagent Solutions for Single-Cell RNA-Seq QC

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Analysis Ecosystems | Scanpy (Python), Seurat (R) | Comprehensive frameworks for end-to-end scRNA-seq analysis, including QC metric calculation and visualization [33]. |

| Doublet Detection | Scrublet, DoubletFinder | Computational tools to identify and remove multiplets—droplets or wells containing more than one cell [35] [34]. |

| QC Metric Calculators | calculate_qc_metrics (Scanpy), PercentageFeatureSet (Seurat) |

Functions to compute essential QC covariates: counts, genes, and mitochondrial/ribosomal percentages [35] [36]. |

| Batch Effect Correction | BUSseq, Scanorama, scVI | Algorithms to integrate data across multiple batches or experimental runs, addressing technical variation [37]. |

| Normalization Methods | Log-Normalization, SCTransform | Techniques to remove technical variation (e.g., sequencing depth) to make counts comparable across cells [38]. |

| Visualization Packages | Matplotlib, Seaborn (Python); ggplot2 (R) | Libraries for generating diagnostic QC plots (violin plots, scatter plots) to guide threshold selection [35] [34]. |

Scanpy Protocol for QC Metric Calculation

Data Input and Initial Setup

The Scanpy workflow begins with data import and initialization. The code below demonstrates reading a 10X Genomics dataset and setting up the analysis environment.

Calculation of QC Metrics

Scanpy provides the calculate_qc_metrics function to compute comprehensive quality control statistics. This function calculates both basic metrics and proportions for specific gene populations.

Visualization of QC Metrics

Visualization is crucial for identifying appropriate filtering thresholds. Scanpy offers built-in plotting functions for QC metric visualization.

Cell and Gene Filtering

Based on the visualized distributions, apply filtering to remove low-quality cells and genes.

Doublet Detection

Doublets (multiple cells labeled as one) can lead to misclassification and must be identified and removed.

Seurat Protocol for QC Metric Calculation

Data Input and Seurat Object Creation

The Seurat workflow in R begins with data import and creation of a Seurat object.

Calculation of QC Metrics

Seurat calculates QC metrics using the PercentageFeatureSet function and adds them to the object's metadata.

Visualization of QC Metrics

Seurat provides multiple visualization approaches to inspect QC metric distributions.

Cell Filtering

Apply filtering thresholds based on the visualized distributions.

Comparative Analysis of QC Metrics and Parameters

The calculation and interpretation of QC metrics follows similar principles across analysis ecosystems, though implementation details differ. The following table provides a direct comparison of key metrics and typical filtering parameters.

Table 2: Comparison of QC Metrics and Filtering Parameters Between Scanpy and Seurat

| QC Metric | Scanpy Terminology | Seurat Terminology | Biological/Technical Significance | Typical Thresholds |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of detected genes | n_genes_by_counts |

nFeature_RNA |

Indicates library complexity; low values suggest poor-quality cells, high values may indicate doublets [4]. | 200-2500 (per cell) |

| Total UMI counts | total_counts |

nCount_RNA |

Represents sequencing depth/count depth; extreme values indicate issues with cell integrity or capture efficiency [4]. | 500-35000 (per cell) |

| Mitochondrial percentage | pct_counts_mt |

percent.mt |

High values (>20%) suggest cell stress or degradation due to cytoplasmic RNA loss [34] [39]. | <5-10% (highly cell-type dependent) |

| Ribosomal percentage | pct_counts_ribo |

percent.rb |

Varies by cell type and function; extreme deviations may indicate issues [34]. | Context-dependent |

| Doublet score | doublet_score |

Doublet_score |

Probability of a barcode representing multiple cells; requires batch/dataset-specific thresholding [35] [34]. | >0.3 (dataset-specific) |

Advanced QC Considerations and Methodological Notes

Batch-Aware Quality Control

When working with multiple samples or batches, QC should be performed in a batch-aware manner, as technical variation between batches can significantly affect metric distributions [37].

Automated Thresholding with MAD

For large datasets, manual threshold inspection becomes impractical. Automated approaches using Median Absolute Deviation (MAD) provide a robust statistical alternative [4].

Compositional Data Analysis Approaches

Emerging methodologies based on Compositional Data Analysis (CoDA) offer alternative approaches to scRNA-seq normalization and processing. These methods explicitly treat scRNA-seq data as compositional, addressing fundamental properties including scale invariance, sub-compositional coherence, and permutation invariance [38]. The centered-log-ratio (CLR) transformation shows particular promise for improving cluster separation and trajectory inference.

Proper calculation and interpretation of QC metrics establishes the foundation for all subsequent scRNA-seq analyses. The protocols detailed here for Scanpy and Seurat enable researchers to systematically assess data quality, identify technical artifacts, and make informed filtering decisions. The filtered dataset resulting from these QC procedures serves as input for downstream analyses including normalization, dimensionality reduction, clustering, and differential expression.

Quality control must be viewed as an iterative process rather than a one-time procedure. As cell type annotations are refined through subclustering and marker gene identification, researchers should re-examine QC metrics within specific cell populations, as certain biological conditions (e.g., metabolic activity, cell cycle stage) may manifest in ways that resemble technical artifacts. This ongoing quality assessment ensures that biological discoveries rest upon a robust analytical foundation, ultimately supporting valid scientific conclusions in single-cell transcriptomics research.

Quality control (QC) represents a critical first step in single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) analysis pipelines, directly influencing all subsequent biological interpretations. Effective QC aims to remove low-quality cells while preserving biological heterogeneity, a balance that requires careful consideration of filtering methodologies. The central challenge lies in distinguishing technical artifacts from genuine biological variation, particularly as scRNA-seq data is inherently "drop-out" prone with excessive zeros due to limited mRNA capture [4]. This protocol examines two principal approaches for setting QC thresholds: manual curation based on researcher expertise and automated outlier detection using Median Absolute Deviation (MAD), framing this comparison within the broader context of quality control covariate implementation for scRNA-seq research.

The fundamental QC covariates consistently employed across scRNA-seq workflows include: (1) library size (total UMI counts per barcode), where low values may indicate poor mRNA capture efficiency; (2) number of detected genes per cell, with low values suggesting compromised cell integrity or failed reverse transcription; and (3) mitochondrial gene percentage, where elevated levels often signal cellular stress or broken membranes that have leaked cytoplasmic RNA [4] [40]. The accurate measurement of these metrics depends on proper experimental design and computational processing, including the identification of mitochondrial genes through prefix matching ("MT-" for human, "mt-" for mouse) [4].

Each filtering approach offers distinct advantages and limitations. Manual curation leverages researcher intuition and biological context but introduces subjectivity, while MAD-based automation provides standardization and reproducibility at the potential cost of overlooking dataset-specific nuances. This Application Note provides detailed methodologies for implementing both approaches, supported by quantitative comparisons and practical implementation frameworks to guide researchers in selecting appropriate QC strategies for their specific experimental contexts.

Theoretical Foundation and QC Metrics

Statistical Basis for QC Thresholding

The statistical foundation for QC filtering rests on distinguishing outliers from the core distribution of quality metrics. Manual curation typically assumes that quality metrics follow approximately normal distributions after appropriate transformation, with outliers representing low-quality cells. The MAD method operates on a more robust statistical framework, relying on the median as a central tendency measure resistant to outliers, with the MAD defined as:

MAD = median(|X_i - median(X)|)

where X_i represents the QC metric for each cell [4]. This robust measure of variability forms the basis for automated outlier detection, typically flagging cells that deviate by more than 3-5 MADs from the median as potential low-quality candidates [4] [40].

The relationship between QC metrics and cell quality stems from well-characterized biological and technical phenomena. Low library sizes and few detected genes often indicate poor mRNA capture due to cell damage, low reaction efficiency, or incomplete lysis [40]. Elevated mitochondrial percentages (typically >10-20%) frequently reflect cellular stress or compromised membranes, as mitochondrial RNAs remain relatively protected within organelles when cytoplasmic mRNA leaks out [4]. However, these general principles require contextual interpretation, as different cell types and tissues exhibit natural variations in these metrics.

Biological Confounding in QC Interpretation

A critical consideration in QC thresholding involves recognizing when apparent quality issues actually reflect genuine biological variation. As highlighted in spatial transcriptomics studies, certain brain regions like white matter naturally exhibit higher mitochondrial percentages and lower detected genes compared to gray matter due to biological composition rather than technical artifacts [40]. Similarly, cell cycle phase, metabolic activity, and specialized cellular functions can influence these metrics, potentially leading to inappropriate filtering of biologically distinct populations if QC thresholds are applied without discretion.

This biological confounding presents particular challenges for automated methods, which may systematically remove valid cell subtypes based on statistical outliers without biological context. Manual curation allows researchers to incorporate tissue-specific knowledge and experimental design considerations, though this introduces its own biases. The optimal approach often involves iterative evaluation, where initial automated filtering is followed by biological validation of removed cells to ensure meaningful population retention.

Methodological Approaches

Manual Curation Protocol

Step 1: QC Metric Calculation Begin by computing essential quality metrics from the raw count matrix using established tools:

- Utilize

sc.pp.calculate_qc_metricsin Scanpy orcalculateQCMetricsin scater to generate:total_counts: Total UMI counts per cell (library size)n_genes_by_counts: Number of genes with positive counts per cellpct_counts_mt: Percentage of total counts mapping to mitochondrial genes [4]

- Properly identify mitochondrial genes using prefix matching appropriate to species:

- Human:

adata.var["mt"] = adata.var_names.str.startswith("MT-") - Mouse:

adata.var["mt"] = adata.var_names.str.startswith("mt-")[4]

- Human:

Step 2: Visualization for Threshold Selection Generate comprehensive visualizations to inform threshold selection:

- Create violin plots for each QC metric to assess overall distributions

- Generate scatter plots of totalcounts vs. ngenesbycounts, colored by pctcountsmt to identify correlations between metrics

- Produce histograms with density estimates to visualize metric distributions [4]

- Examine spatial distributions of QC metrics when working with spatial transcriptomics data to identify tissue-structure correlations [40]

Step 3: Context-Dependent Threshold Determination Establish thresholds based on visualization patterns and biological context:

- For standard tissues without known extreme biological variation:

- Library size: Typically 500-5,000 counts depending on protocol

- Detected genes: Typically 200-2,500 genes depending on cell type

- Mitochondrial percentage: Typically 5-20% maximum [4]

- For specialized tissues (e.g., brain):

- Adjust thresholds to account for biological variation between regions

- Consider higher mitochondrial thresholds for metabolically active cells

- Implement region-specific filtering when possible [40]

Step 4: Application and Documentation Apply selected thresholds systematically:

- Filter cells using

sc.pp.filter_cellsin Scanpy or similar functions - Record all thresholds and rationales in metadata for reproducibility

- Retain pre-filtered objects for comparative analysis

Table 1: Representative Manual Threshold Ranges for Different Sample Types

| Sample Type | Library Size Range | Detected Genes Range | Mitochondrial % Threshold | Special Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells | 1,000-10,000 | 500-2,000 | 5-10% | Low RNA content, small cells |

| Brain Tissue (Neurons) | 5,000-50,000 | 1,500-5,000 | 5-15% | Region-specific variation in white vs. gray matter |

| Cancer Cell Lines | 2,000-20,000 | 1,000-4,000 | 5-20% | Aneuploidy may increase detected gene count |

| Primary Epithelial Cells | 3,000-30,000 | 1,000-3,500 | 5-12% | Cell size variation affects RNA content |

Automated MAD-Based Filtering Protocol

Step 1: MAD Calculation and Threshold Definition Compute MAD-based thresholds for each QC metric:

- Calculate median values for each QC metric across all cells

- Compute MAD values using:

MAD = median(|X_i - median(X)|) - Define outlier thresholds using multiples of MAD (typically 3-5 MADs):

- Lower bounds:

median(metric) - k * MAD(for library size, detected genes) - Upper bounds:

median(metric) + k * MAD(for mitochondrial percentage) [4]

- Lower bounds:

Step 2: Adaptive Threshold Application Implement MAD filtering with dataset-specific considerations:

- Apply more conservative thresholds (5 MADs) for heterogeneous samples

- Use more stringent thresholds (3 MADs) for homogeneous cell populations

- Consider asymmetric bounds for different metrics (e.g., stricter upper bounds for mitochondrial percentage)

Step 3: Validation and Adjustment Verify automated filtering results:

- Compare pre- and post-filtering distributions using visualization

- Check for systematic removal of specific cell types or conditions

- Adjust MAD multipliers if biological populations are disproportionately affected

Step 4: Implementation Code Framework

Table 2: MAD Multiplier Selection Guidelines Based on Dataset Characteristics

| Dataset Characteristic | Recommended MAD Multiplier | Rationale | Potential Risks |

|---|---|---|---|

| Homogeneous cell population | 3-4 | Reduced biological variation in metrics | May retain technical outliers |

| Heterogeneous tissue (multiple cell types) | 4-5 | Accommodates biological variation in RNA content | May retain low-quality cells from rare populations |

| Known technical issues (e.g., batch effects) | 5+ | Conservative approach to remove artifacts | Potential loss of biological outliers |

| Rare cell population focus | 5+ (with visual validation) | Maximizes sensitive population retention | Increased technical noise carryover |

Comparative Analysis and Implementation Guidelines

Performance Comparison Across Methodologies

Table 3: Comparative Analysis of Manual vs. Automated Filtering Approaches

| Characteristic | Manual Curation | MAD-Based Filtering | Hybrid Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Subjectivity | High - depends on researcher experience | Low - standardized statistical approach | Moderate - automated with manual validation |

| Reproducibility | Low - difficult to replicate exactly | High - precisely reproducible parameters | Moderate - reproducible with documented adjustments |

| Handling of Large Datasets | Time-consuming - requires individual assessment | Scalable - automated processing | Scalable with focused manual review |

| Biological Context Integration | Excellent - can incorporate tissue knowledge | Poor - purely statistical without biological context | Good - automated with context-informed parameters |

| Adaptation to New Technologies | Flexible - can adjust based on principle | Requires validation and potential parameter adjustment | Flexible framework with empirical validation |

| Risk of Over-filtering | Variable - can be minimized with expertise | Moderate - may remove biological outliers | Low - with careful validation steps |

| Implementation Complexity | Low technical barrier | Moderate - requires programming expertise | Moderate - combined technical and biological expertise |

Decision Framework for Method Selection

The choice between manual and automated filtering approaches depends on multiple experimental factors:

Select manual curation when:

- Working with novel tissue types with unknown expected metric ranges

- Analyzing datasets with known biological extreme subpopulations

- Processing small-scale pilot studies where individual assessment is feasible

- Addressing complex spatial transcriptomics datasets with clear histological correlations [40]