Solving Convergence Issues in Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is a cornerstone of modern evolutionary biology, epidemiology, and drug development, yet it is frequently hampered by convergence issues in Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling.

Solving Convergence Issues in Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Biomedical Research

Abstract

Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is a cornerstone of modern evolutionary biology, epidemiology, and drug development, yet it is frequently hampered by convergence issues in Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling. This article provides a comprehensive framework for diagnosing, troubleshooting, and resolving these challenges. We cover foundational concepts of MCMC convergence, explore advanced methodological workflows from sequence alignment to tree inference, and detail specialized diagnostics for the complex parameter of tree topology. By comparing state-of-the-art software and validation techniques, this guide empowers researchers to achieve robust, reproducible, and biologically reliable phylogenetic estimates, which are critical for applications ranging from pathogen tracing to vaccine development.

Understanding the Root Causes of MCMC Non-Convergence in Phylogenetics

In Bayesian phylogenetic inference, researchers use Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) algorithms to approximate posterior distributions of phylogenetic trees. Standard diagnostic practices involve investigating trace plots and calculating Effective Sample Size (ESS) for continuous parameters to evaluate convergence and mixing. However, these standard methods face a critical challenge: they are fundamentally incompatible with the tree topology parameter. This creates a significant diagnostic blind spot, as the tree topology is often the parameter of primary scientific interest, especially in outbreak investigation and epidemic monitoring [1].

This technical support guide explains why tree topology resists standard diagnostics and provides researchers with methodologies to properly assess topological convergence in their analyses.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't I use standard Effective Sample Size (ESS) diagnostics for tree topology?

Standard ESS calculations are designed for continuous, univariate parameters. Tree topology, in contrast, is a discrete, high-dimensional parameter that does not inhabit a metric space where traditional ESS measures apply. Diagnostics from software packages like Tracer, Beastiary, or CODA are developed specifically for simple continuous parameters and cannot directly evaluate topology [1].

2. What are the risks of relying solely on continuous parameter convergence?

If diagnostics suggest satisfactory MCMC convergence and mixing for continuous parameters, it is often incorrectly assumed the topology has also converged. This is problematic because:

- The tree topology may still be poorly sampled

- The consensus phylogeny may be inaccurate

- Scientific conclusions about evolutionary relationships may be flawed

- Downstream analyses in drug development may be compromised [1]

3. What methods are available specifically for topological diagnostics?

Recent methodological advancements include:

- Tree ESS metrics that extend ESS principles to topological space

- Split-based diagnostics that treat the presence of each clade as an individual parameter

- Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) ESS that projects high-dimensional trees to lower dimensions

- Phylogenetic distance metrics for comparing topological samples [1]

4. How many replicate MCMC runs are necessary for robust topological assessment?

Running multiple independent replicates is crucial for proper topological convergence assessment. Comparing topological samples across replicates using phylogenetic distance metrics provides more reliable convergence evaluation than single-run diagnostics alone [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Assessing Topological Convergence

Problem: Suspected Topological Non-Convergence

Symptoms:

- Continuous parameters show good ESS (>200) but tree estimates appear unstable

- Clade support values differ substantially between replicate analyses

- Consensus trees from different runs show conflicting relationships

Diagnostic Protocol:

Step 1: Calculate Multiple Phylogenetic Distance Metrics

Use different classes of distance metrics to compare topological samples within and between runs:

Table: Phylogenetic Distance Metrics for Topological Comparison

| Metric Type | Specific Metrics | What It Measures | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Partition/Branch Length-Based | Robinson-Foulds (RF), Weighted RF, Branch Score | Partition similarity between trees, with or without branch length consideration | RF counts different bipartitions; weighted RF incorporates branch length differences [1] |

| Path Length-Based | Path Difference, Kendall-Colijn | Differences in tip-to-tip path lengths or MRCA-to-root distances | Path Difference uses path lengths between tips; Kendall-Colijn focuses on root-to-MRCA distances [1] |

| Operation-Based | Subtree-Prune-Regraft (SPR) Distance | Minimum number of subtree prune-regraft operations to transform one tree to another | Measures edit distance between trees [1] |

Step 2: Compare Within-run and Between-run Topological Variation

Calculate pairwise distances between trees:

- Within-run distances: Distances between all trees in a single MCMC run

- Between-run distances: Distances between trees from different independent runs

If between-run variation significantly exceeds within-run variation, topological non-convergence is likely.

Step 3: Visualize Topological Sampling Using Multidimensional Scaling (MDS)

Project high-dimensional trees into 2D or 3D space using MDS based on phylogenetic distances:

Step 4: Implement Split-based Diagnostics

Treat each possible split (clade) as a binary parameter and monitor:

- Frequency of appearance in posterior samples

- ESS of each split using binary diagnostic methods

- Convergence of support for key clades across runs

Interpretation Guidelines:

- Good topological mixing: MDS shows overlapping clusters from different runs

- Problematic mixing: MDS shows distinct clusters from different runs

- Adequate topological ESS: Values >200 for key splits and overall tree metrics

Experimental Protocols for Topological Diagnostics

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Topological Convergence Assessment

Materials and Software Requirements:

- Posterior tree samples from multiple independent MCMC runs

- Phylogenetic analysis software (e.g., BEAST, MrBayes)

- Topological diagnostic tools (e.g., R packages phytools, apTreeshape)

Table: Research Reagent Solutions for Topological Diagnostics

| Reagent/Software | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| BEAST2 | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Sampling trees and parameters from posterior distribution [1] |

| Tracer | MCMC diagnostic analysis | Evaluating convergence of continuous parameters [1] |

| R package phytools | Phylogenetic tools | Calculating phylogenetic distance metrics [1] |

| R package treescape | Statistical exploration of landscapes of trees | MDS visualization and analysis of tree distributions [1] |

| StatAlign | Bayesian co-estimation of alignment and phylogeny | Structural phylogenetics with protein structure integration [2] |

Methodology:

- Run minimum of 4 independent MCMC analyses with different starting seeds

- For each run, calculate tree ESS using multiple phylogenetic distance metrics

- Compute pairwise distance matrices within and between runs

- Perform MDS projection of trees from all runs combined

- Calculate frequency and ESS for key splits across runs

- Compare consensus trees from different runs using distance metrics

Expected Results:

- Converged analysis: <5% difference in within-run vs between-run distances

- Adequate sampling: Tree ESS >200 for multiple distance metrics

- Stable clades: >95% concordance in well-supported clades (posterior probability >0.9) across runs

Protocol 2: Topological Diagnostic Workflow for Large Datasets

Challenge: Standard topological diagnostics become computationally prohibitive with large trees (100+ taxa)

Optimized Approach:

- Subsample posterior trees (every 1000th tree) to reduce computational burden

- Focus on key clades of scientific interest rather than full topology

- Use fast distance metrics like Robinson-Foulds without branch lengths

- Implement approximate methods for large trees using cluster computing

Key Recommendations for Research Practice

- Never rely solely on continuous parameter diagnostics - always assess topological convergence specifically

- Use multiple phylogenetic distance metrics - different metrics capture different aspects of topological differences

- Run multiple independent replicates - essential for proper topological convergence assessment

- Report topological diagnostics in publications including tree ESS values and between-run comparisons

- Develop field-specific standards for topological convergence similar to ESS thresholds for continuous parameters

Future Directions in Topological Diagnostics

Emerging methodologies include:

- Integration of protein structure in phylogenetic models to improve topological inference [2]

- Novel topology proposals for improved MCMC mixing in tree space [2]

- Machine learning approaches for detecting topological convergence issues

- Standardized benchmarking of topological diagnostic methods across diverse datasets

By implementing these topological diagnostic protocols, researchers can significantly improve the reliability of phylogenetic inferences in Bayesian analysis, leading to more robust conclusions in evolutionary biology, outbreak tracking, and drug development research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why can't I use standard trace plots and ESS for evaluating tree topology convergence?

Standard trace plots and Effective Sample Size (ESS) are designed for continuous parameters [3] [4]. They operate on numerical values, calculating autocorrelation and variance to estimate sampling efficiency. Tree topology, however, is a discrete, high-dimensional parameter [5]. Calculating autocorrelation or variance between two distinct tree topologies using conventional methods is not meaningful, which is why these standard diagnostics are incompatible with the topology parameter [3] [4].

2. What are the risks of only checking convergence for continuous parameters?

Assuming that good convergence for continuous parameters guarantees good convergence for tree topologies is potentially problematic [3] [4]. The tree topology is often the parameter of key interest and can heavily influence the estimation of other parameters, such as substitution rates and divergence dates [5]. It is often more difficult for an MCMC chain to explore tree space than the space of a continuous parameter, meaning the ESS for topology is frequently lower than for other parameters [5]. Therefore, an analysis can appear convergent for all continuous parameters while still being poorly sampled for tree topologies, leading to incorrect biological inferences [5].

3. What is a Topology Trace Plot and how do I interpret it?

A topology trace plot is a diagnostic graph that functions analogously to a standard trace plot but for tree topologies [5]. The Y-axis shows the phylogenetic distance of each sampled tree from a chosen reference tree, while the X-axis shows the generation at which each sample was taken [5].

- Good convergence and mixing: The trace should appear stationary, with no long-term trends, and show rapid oscillation between high and low distances, indicating the chain is effectively exploring different areas of tree space [5].

- Poor mixing: The trace may show long, flat sections, indicating the chain is stuck in one region of tree space for many generations (high autocorrelation) before jumping to another [5]. It is good practice to generate multiple topology traces using different reference trees (e.g., a posterior tree, a consensus tree) to get a robust assessment [3] [4].

4. What methods are available for calculating a topology-specific ESS?

Several methods have been developed to estimate an ESS for tree topologies, each with a different approach [3] [4]:

- Pseudo-ESS: Calculates the ESS of the vector of phylogenetic distances from a focal tree to all other trees in the sample. The computation is repeated for every tree as the focal tree, and the lowest and median values are reported [3] [4].

- Approximate ESS: Estimates a topological autocorrelation time by determining the thinning interval at which the average phylogenetic distance between subsequent samples stops increasing. The ESS is then approximated as the sample size divided by this autocorrelation time [3] [4].

- Split Frequency ESS: Treats each possible split (branch) in the tree as a binary parameter (present/absent). The ESS is then computed for these binary split indicators [3] [4].

- Fréchet Correlation ESS & MDS ESS: These are more advanced metrics that use Fréchet correlations or multidimensional scaling (MDS) to project trees into a space where standard ESS calculations can be applied [3] [4].

5. What is the recommended ESS threshold for tree topologies?

While the field has settled on a rule of thumb that the ESS of all parameters should be at least 200 for posterior distributions to be accurately inferred [5], this threshold is also pragmatically applied to topology ESS values. When the topological ESS is below this threshold, researchers should consider running longer analyses, using Metropolis Coupling (MC³), or adjusting tree proposal moves in their MCMC algorithm [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Topological ESS Despite High Continuous Parameter ESS

Problem Your analysis shows that the ESS for continuous parameters (e.g., branch lengths, substitution rates) is well above 200, but the topological ESS is unacceptably low.

Solution

- Run Multiple Replicates: Always run at least two independent MCMC analyses from different starting points. This allows you to check if the chains have converged on the same topological distribution and combine samples post-hoc [3] [4].

- Use Metropolis Coupling (MC³): Also known as "heated chains," this technique runs multiple chains at different "temperatures." Heated chains can more easily traverse barriers in tree space, helping the main (cold) chain escape local optima and improve mixing [5].

- Adjust MCMC Proposal Mechanisms: Review and optimize the parameters of tree topology proposal mechanisms in your Bayesian software (e.g., the subtree prune-and-regraft (SPR) move tuning parameter in BEAST or MrBayes). Better-tuned proposals can lead to more efficient exploration of tree space [3].

Issue 2: Interpreting Conflicting Diagnostics

Problem Different topological convergence diagnostics (e.g., Pseudo-ESS vs. Split Frequency ESS) give you different values, making it difficult to conclude whether convergence has been achieved.

Solution

- Use a Conservative Approach: Do not rely on a single diagnostic. The Multidimensional Scaling (MDS) ESS is noted to be a more conservative measure [3] [4]. If this and other metrics are above the threshold, you can be more confident.

- Cross-validate with Visual Diagnostics: Generate topology trace plots and "jump distance" plots for your chains [5]. If the traces from multiple replicates overlap and appear stationary, and the jump distances show low autocorrelation, it is a good visual indicator that the low ESS from one metric might be an underestimate or that the analysis is acceptable.

- Check Split Frequencies: Compare the consensus trees and split frequencies between independent replicates. If the estimated trees are similar and the split frequencies agree, it is a strong sign of convergence, even if some ESS metrics are low [5].

The following table summarizes the key phylogenetic distance metrics used in topological diagnostics.

Table 1: Summary of Phylogenetic Distance Metrics for Topological Diagnostics [3] [4]

| Metric Name | Core Concept | Categories of Metrics | Example Calculation Result |

|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson-Foulds (RF) | Counts partitions (splits) present in one tree but not the other. | Partition-based | 2 |

| Weighted Robinson-Foulds | Sum of absolute differences in branch lengths for corresponding partitions. | Partition-based | 17 |

| Branch Score | Square root of the sum of squares of branch length differences. | Partition-based | 7.42 |

| Path Difference | Square root of the sum of squares of differences in tip-to-tip path lengths. | Path-based | 2 |

| Kendall-Colijn (λ=0) | Square root of the sum of squares of differences in root-to-MRCA path lengths. | Path-based | 2.45 |

| Subtree-Prune-Regraft (SPR) | Minimum number of SPR operations needed to transform one tree into another. | Operation-based | 1 |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Topological Convergence

Objective: To determine if a Bayesian phylogenetic MCMC analysis has adequately sampled the posterior distribution of tree topologies.

Materials: MCMC output samples (tree files and log files) from two or more independent runs.

Software & Reagents: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Topological Convergence Analysis

| Item | Function | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| R Programming Environment | Platform for running convergence diagnostic packages. | v4.3.0 or later [3] [4] |

treess R Package |

Computes various topological ESS estimators (Fréchet, Split Frequency, MDS). | Version 1.0.1 [3] [4] |

TreeDist & phangorn R Packages |

Calculate a wide array of phylogenetic distances between trees. | Required for distance-based diagnostics [3] [4] |

convenience R Package |

Calculates per-split ESS values. | An alternative approach [3] [4] |

Methodology:

- Compute Multiple Topological ESS Values: Using the

treesspackage, calculate several ESS metrics (e.g., Pseudo-ESS, Split Frequency ESS, MDS ESS). Report both the minimum and median values where applicable [3] [4]. - Generate Topology Trace Plots: For each independent MCMC run, plot the phylogenetic distance from a fixed reference tree (e.g., the maximum clade credibility tree from a combined analysis) against the MCMC generation [5]. Overlay the traces from all replicates on the same plot.

- Visualize with Jump Distance Plots: Create a plot that shows the average phylogenetic distance between sampled trees as a function of the thinning interval (lag) [5]. The point at which this distance plateaus indicates the autocorrelation time.

- Compare Consensus Topologies: Build a consensus tree (e.g., majority-rule) from each independent chain and compare them visually and using a metric like the Robinson-Foulds distance.

- Synthesize Evidence: Convergence is supported if: (a) multiple topological ESS values are >200, (b) topology trace plots from all replicates overlap and look like "hairy caterpillars", (c) jump distances plateau at a low lag, and (d) consensus topologies from independent runs are highly similar.

Diagnostic Workflow and Logical Relationships

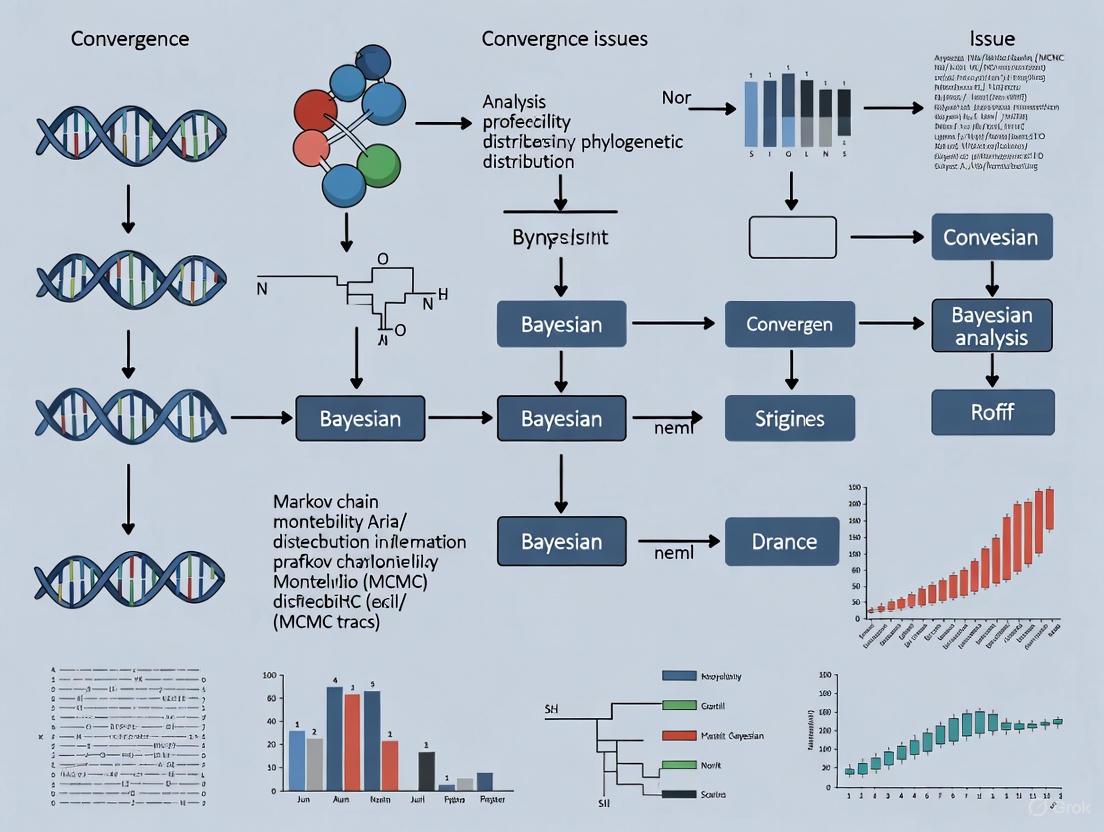

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for assessing topological convergence based on the synthesized diagnostics.

Metric Definitions and Core Concepts

What are phylogenetic distance metrics and why are they important?

Phylogenetic distance metrics are quantitative measures used to calculate the difference between two phylogenetic trees. They are essential tools for assessing the accuracy of phylogenetic reconstruction methods, comparing alternative tree hypotheses, evaluating convergence in Bayesian analyses, and summarizing posterior distributions of trees. In Bayesian phylogenetics, they help determine if multiple Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) runs have converged to the same posterior distribution by measuring distances between resulting trees.

How does the Robinson-Foulds (RF) metric work?

The Robinson-Foulds (RF) metric, also called symmetric difference metric, is a widely used method for comparing phylogenetic trees. It operates by comparing the "splits" or "bipartitions" induced by each branch in the trees:

- Calculation method: For each tree, every internal branch defines a split (bipartition) of taxa into two sets. The RF distance counts the number of splits present in one tree but not the other.

- Mathematical definition: The RF distance between trees T1 and T2 equals (A + B)/2, where A is the number of splits in T1 but not T2, and B is the number of splits in T2 but not T1. Some implementations use the unnormalized sum (A + B) without dividing by 2 [6].

- Simple example: Consider two unrooted trees T1 and T2 with identical leaf sets. If T1 has 3 unique splits and T2 has 5 unique splits (with 15 shared splits), the RF distance would be (3 + 5) = 8 [6] [7].

- Software implementations: Available in popular packages including PHYLIP, RAxML, DendroPy, R packages TreeDist and phangorn, and Python's ete3 toolkit [6].

What is the Path Difference metric?

The Path Difference metric measures dissimilarity between trees based on pairwise leaf distances:

- Calculation method: For each pair of leaves, compute the distance between them in each tree (sum of branch lengths along the path). The squared path difference is the sum of squared differences between these pairwise distances across all leaf pairs [8] [9].

- Mathematical properties: This metric can be expressed as a squared Euclidean distance, making it mathematically convenient for certain applications including Bayes estimator calculations [8].

- Theoretical foundation: The expected value of the squared path-difference distance has been studied under both uniform and Yule model distributions of trees, providing a statistical foundation for its application [9] [10].

What is SPR Distance?

Subtree Prune and Regraft (SPR) distance is a rearrangement-based metric:

- Calculation method: SPR distance measures the minimum number of SPR operations needed to transform one tree into another. An SPR operation involves cutting a branch (pruning a subtree) and reattaching it elsewhere in the tree [11].

- Computational complexity: Computing SPR distance is NP-hard in general, making it computationally challenging for large trees despite its biological relevance.

- Biological relevance: SPR operations mimic biological processes like horizontal gene transfer and recombination, making this metric particularly relevant for studying genomes with complex evolutionary histories [11].

Comparative Analysis of Distance Metrics

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Phylogenetic Distance Metrics

| Metric | Computational Complexity | Handles Branch Lengths? | Biological Interpretation | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Robinson-Foulds | O(n) with efficient algorithms [7] | Unweighted version: No; Weighted version: Yes [11] | Compares topological splits/partitions | General tree comparison, consensus evaluation, cluster analysis |

| Path Difference | O(n²) due to pairwise comparisons [8] | Yes, inherently uses branch lengths | Measures differences in pairwise evolutionary distances | Bayes estimator calculations, theoretical studies |

| SPR Distance | NP-hard in general [11] | Typically ignores branch lengths | Measures minimal number of evolutionary rearrangements | Studying recombination, horizontal gene transfer, tree space exploration |

Table 2: Advantages and Limitations of Different Metrics

| Metric | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Robinson-Foulds | Intuitive concept, fast computation, widely implemented, metric properties [6] | Sensitive to tree resolution, saturates quickly, ignores branch lengths, counterintuitive in some cases [6] |

| Path Difference | Incorporates branch lengths, mathematical properties well-studied, Euclidean embedding [8] [9] | Computationally intensive for large trees, sensitive to branch length measurement error |

| SPR Distance | Biologically meaningful, directly related to evolutionary processes | Computationally challenging, typically ignores branch lengths |

Troubleshooting Guide for Metric Selection and Interpretation

How do I choose the appropriate metric for my analysis?

Selecting the right distance metric depends on your biological question and data characteristics:

- Use Robinson-Foulds when: You need fast computation on large trees, are primarily concerned with topological differences, and want to compare results with existing literature [6].

- Use Path Difference when: Branch lengths are biologically important in your analysis, and you need mathematical properties of Euclidean distances for downstream statistical analysis [8].

- Use SPR Distance when: Studying evolutionary processes involving rearrangement events like horizontal gene transfer, or when you need a biologically meaningful measure of tree similarity despite computational cost [11].

- Consider generalized RF distances: Newer "Generalized" Robinson-Foulds metrics address some limitations of the original RF metric by recognizing similarity between similar but non-identical splits [6].

Why do I get counterintuitive RF distances, and how can I address this?

The RF metric has known limitations that can produce surprising results:

- Saturation effect: The metric quickly reaches its maximum value, making it difficult to distinguish between moderately and very different trees [6].

- Lack of sensitivity: RF may fail to detect important topological differences, as it can take two fewer distinct values than there are taxa in a tree [6].

- Tree shape dependence: Values can depend on tree shape rather than just topological differences [6].

- Mitigation strategies:

- For Bayesian analyses, consider using the Bayes estimator approach with path difference or other metrics to find trees that minimize expected distance to the true tree [8].

- Use information-theoretic generalizations of RF distances, such as the Clustering Information Distance implemented in the TreeDist R package [6].

- Consider quartet-based distances as alternatives that may provide better sensitivity to certain topological differences [6].

How can I use distance metrics to diagnose convergence in Bayesian phylogenetic analysis?

Distance metrics play a crucial role in assessing MCMC convergence:

- Comparing multiple runs: Calculate RF distances between trees from independent MCMC runs to assess whether they are sampling from the same distribution.

- Within-chain stability: Monitor distance between trees sampled at different time points within a single chain to assess stability.

- Posterior summarization: Use the Bayes estimator approach to find a tree that minimizes the expected distance to trees in the posterior sample, providing a point estimate that best represents the posterior distribution [8].

- Cluster analysis: Apply clustering algorithms (like those implemented in Stockham et al.'s work) to identify distinct tree topologies in posterior samples, which can reveal multimodal posterior distributions [7].

Experimental Protocols and Implementation

Protocol 1: Computing Robinson-Foulds Distance with Efficient Algorithm

This O(n) algorithm uses bitwise operations for efficient RF calculation [7]:

- Leaf fingerprinting: Assign each leaf a random bit sequence (fingerprint) of specified length (BITS)

- Tree traversal (T1): Starting at a reference leaf (typically leaf 0), traverse T1 and compute for each internal edge the XOR of fingerprints of all leaves in the subtree

- Dictionary construction: Store computed XOR values in a dictionary for T1

- Tree traversal (T2): Similarly traverse T2, computing XOR values for each internal edge

- Distance calculation: For each edge in T2, check if its fingerprint exists in T1's dictionary; count missing partitions

- Result: The RF distance equals the number of partitions unique to either tree

Tree Comparison Workflow Using Hash-Based RF Distance Calculation

Protocol 2: Bayes Estimator Tree Reconstruction Using Path Difference

This method finds the tree that minimizes expected distance to the true tree [8]:

- Posterior sampling: Run Bayesian MCMC analysis to obtain a sample of trees from the posterior distribution

- Distance selection: Choose an appropriate distance metric (e.g., squared path difference)

- Hill-climbing search: Starting from an initial tree, use nearest-neighbor interchange (NNI) moves to find the tree minimizing the average distance to posterior samples

- Validation: Compare the Bayes estimator tree with maximum a posteriori (MAP) and maximum likelihood (ML) trees using multiple metrics

- Application: Studies show Bayes estimator trees under squared path difference tend to perform well in terms of both path difference and RF distances to the true tree [8]

Protocol 3: Cluster Analysis of Tree Sets Using RF Distance

Identify groups of similar trees in large collections [7]:

- Distance matrix: Compute pairwise RF distances between all trees in the set

- Initial clustering: Begin with each tree in its own cluster

- Iterative merging: Repeatedly merge the two clusters with smallest average inter-cluster distance

- Cluster evaluation: For each clustering size, compute:

- Number of trees in each cluster

- Cluster diameter (maximum RF distance between any two trees in cluster)

- Average diameter across all clusters

- Consensus trees: Build consensus trees for each cluster to represent common topological features

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software Tools for Phylogenetic Distance Analysis

| Software/Tool | Primary Function | Supported Metrics | Implementation Details |

|---|---|---|---|

| TreeDist R Package | Advanced tree comparison | Robinson-Foulds, Generalized RF, Clustering Information Distance | R implementation with fast C-based functions [6] |

| DendroPy Python Library | Phylogenetic computation | Robinson-Foulds (symmetric difference), quartet distance | Python library with efficient tree handling [6] |

| ETE Toolkit | Tree visualization and analysis | Robinson-Foulds, branch support calculations | Python toolkit with visualization capabilities [6] [12] |

| BEAST | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Tree sampling for posterior distributions, convergence diagnostics | Bayesian MCMC implementation for posterior tree sampling [13] |

| MrBayes | Bayesian phylogenetic inference | Tree sampling, consensus tree building | Parallel MCMC for phylogenetic inference [13] |

| ggtree R Package | Tree visualization | Integration with distance metrics, annotation of tree features | ggplot2-based visualization system [14] |

The Impact of Poor Convergence on Downstream Analyses in Epidemiology and Drug Development

Troubleshooting Guide: Diagnosing MCMC Convergence

Issue: How do I know if my Bayesian phylogenetic analysis has converged? A Bayesian phylogenetic analysis has not converged when the Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampler has not adequately explored the posterior distribution. This leads to unreliable parameter estimates and phylogenetic trees, which can severely impact downstream interpretations in epidemiological tracking and drug target identification [15] [13] [16].

Diagnosis and Solution: Follow this systematic diagnostic procedure to assess convergence. Reliable inference requires that all these checks pass.

Step 1: Run Multiple Independent Analyses Always run at least two, and preferably more, independent MCMC analyses. Start each from a different, random tree topology. Convergence is only plausible if these independent runs produce statistically indistinguishable results [15] [13].

Step 2: Assess Continuous Parameter Convergence Use a diagnostic tool like Tracer to analyze the log files from your independent runs [16].

- Check Effective Sample Size (ESS): The ESS estimates the number of independent samples in your MCMC chain. For reliable estimates, ESS values for all parameters (e.g., branch lengths, substitution rates) should be greater than 200. Values below 200 are flagged in Tracer and indicate high autocorrelation, meaning your samples are not independent and your parameter estimates are unreliable [16].

- Inspect Trace Plots: Plot the sampled parameter values against the MCMC generation number.

- Good Convergence ("Hairy Caterpillar"): The trace should look like a "hairy caterpillar," fluctuating randomly around a stable mean value [16].

- Poor Convergence ("Poor Mixing"): Traces with visible trends, slow drifts, or large, infrequent jumps indicate the chain has not settled into the posterior distribution [16].

- Compare Marginal Densities: Overlay the posterior density distributions for the same parameter from your independent runs. If the runs have converged, these distributions will mostly be placed directly on top of one another [16].

Step 3: Critically Assess Topological Convergence Standard diagnostics like ESS are for continuous parameters and do not assess convergence of the tree topology itself, a critical output. Ignoring this can lead to misplaced confidence [15].

- Check Agreement Between Tree Samples: Compare the posterior sets of trees from your independent runs. If the runs have converged, they should be sampling similar tree topologies with comparable frequencies. Use tools that can compare tree sets (e.g.,

AWTY) [15] [13]. - Visualize Consensus Trees: Build a consensus tree from the posterior tree set of each run and compare them. Major disagreements in clade composition or support indicate topological non-convergence [15].

- Check Agreement Between Tree Samples: Compare the posterior sets of trees from your independent runs. If the runs have converged, they should be sampling similar tree topologies with comparable frequencies. Use tools that can compare tree sets (e.g.,

The flowchart below illustrates this diagnostic workflow.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My ESS is low for some parameters, but the trace looks stable. What should I do? A low ESS indicates high autocorrelation, meaning your samples are not independent and your effective number of data points is low. Even if the trace looks stable, the precision of your estimates will be poor. Solutions include:

- Run a longer analysis: Increase the number of MCMC generations.

- Increase sampling frequency: This can sometimes help, but longer runs are generally more effective.

- Review your model: An overly complex or misspecified model can cause poor mixing. Consider model selection tools like

PartitionFinderorjModelTest[13] [17].

FAQ 2: My runs converge on a phylogeny, but I suspect convergent evolution is misinforming the result. How can I investigate this? Convergent evolution at the molecular level can mislead phylogenetic inference by making non-sister taxa appear closely related [18] [19]. This is a critical concern when identifying drug targets, as it can lead to targeting analogous rather than homologous structures.

- Investigate Site Patterns: Use methods to detect convergent-prone characters. One study found that removing convergence-prone morphological characters improved accuracy; similar logic can be applied to molecular data [19].

- Consider Alternative Models: Explore model-based approaches like convergence-divergence models, which generalize phylogenetic trees to allow for lineages becoming more similar over time (convergence), potentially providing a better fit for data affected by processes like introgression or horizontal gene transfer [18] [20].

FAQ 3: What is the direct impact of poor convergence on an epidemiological study? In epidemiology, poor convergence can lead to:

- Incorrect Outbreak Phylogenies: Misidentification of the transmission cluster topology and spurious relationships between viral sequences [21] [15].

- Biased Evolutionary Rate Estimates: Incorrect estimation of the rate of viral evolution, which directly impacts the calculation of the time to the most recent common ancestor (tMRCA) and can lead to erroneous estimates of when an outbreak began [13].

- Overconfident Conclusions: High posterior probabilities for incorrect clades, leading to strong but misleading support for false transmission links [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software and their primary functions for conducting and diagnosing Bayesian phylogenetic analyses.

| Software/Bioinformatics Tool | Primary Function | Relevance to Convergence & Downstream Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| MrBayes [17] [13] | Bayesian phylogenetic inference | Industry-standard for MCMC analysis of nucleotide, amino acid, and morphological data. |

| BEAST2 [13] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis | Specialized for phylodynamics, molecular dating, and phylogeography; essential for epidemic modeling. |

| Tracer [13] [16] | MCMC diagnostics | Visualizes trace plots, calculates ESS, and compares posterior distributions from independent runs. |

| AWTY [13] | MCMC diagnostics for topology | Specifically designed to assess convergence of phylogenetic tree topologies. |

| PartitionFinder / jModelTest [13] [17] | Model selection | Automates the selection of best-fit substitution models and data partitioning schemes, preventing poor convergence due to model misspecification. |

| RevBayes [13] | Probabilistic graphical modeling | Highly flexible for building custom, complex hierarchical models for specialized research questions. |

Robust Workflows and Advanced Algorithms for Improved Convergence

What is the relationship between sequence alignment, GUIDANCE2, and Bayesian phylogenetic analysis?

Multiple sequence alignment (MSA) is a critical first step in many comparative genomic and phylogenetic analyses. However, inferred alignments often contain errors and can vary substantially depending on the methodology and parameters used. These inaccuracies can introduce significant bias into downstream analyses, such as the detection of positive selection or the estimation of phylogenetic trees in Bayesian inference [22]. GUIDANCE2 is a method developed to quantify the reliability of each position in a multiple sequence alignment, helping researchers identify and handle unreliable regions. When using MAFFT as the alignment program within the GUIDANCE2 framework, researchers can generate a reliability score for their alignment, providing a solid foundation for robust Bayesian phylogenetic analysis and helping to resolve convergence issues that may stem from poor-quality input data [23] [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why should I use GUIDANCE2 with MAFFT for my phylogenetic analysis? GUIDANCE2 provides an integrative methodology to account for major sources of alignment uncertainty, including: (i) uncertainty in the process of indel formation, (ii) uncertainty in the assumed guide tree, and (iii) co-optimal solutions in the pairwise alignments used as building blocks in progressive alignment algorithms. Using MAFFT with GUIDANCE2 has been shown to outperform other methods for detecting unreliable MSA regions, which is crucial because alignment errors can bias downstream Bayesian phylogenetic inference [22].

Q2: Which MAFFT algorithm is best for my dataset? MAFFT offers several algorithms optimized for different scenarios. The table below summarizes the primary algorithms suitable for high-accuracy alignment when working with fewer than 200 sequences, which is typical when using GUIDANCE2 [24].

Table 1: MAFFT Algorithm Selection Guide

| Algorithm Flag | Method Name | Best Use Case | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

--localpair |

L-INS-i | Accurate alignment of sequences with global homology [24]. | Iterative refinement incorporating local pairwise alignment information [24]. |

--globalpair |

G-INS-i | Sequences of similar length [24]. | Iterative refinement incorporating global pairwise alignment information [24]. |

--genafpair |

E-INS-i | Sequences containing large unalignable regions [24]. | Suitable for sequences with multiple domains or long indels [24]. |

Q3: How do I correctly pass MAFFT parameters to GUIDANCE2 on the command line?

A common issue is the incorrect specification of MAFFT parameters through GUIDANCE2's --MSA_Param flag. The recommended and confirmed approach is to wrap all MAFFT arguments in single quotes [25].

Incorrect:

Correct:

This syntax ensures that GUIDANCE2 correctly passes the parameters to the MAFFT executable. Note that the order of parameters can matter; for instance, placing --localpair before --maxiterate prevents the "localpair" text from being misinterpreted as an argument to the --maxiterate flag [25].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: MAFFT Algorithm Not Changing in GUIDANCE2

Symptoms

The GUIDANCE2 log file indicates that MAFFT is running with default parameters (e.g., mafft --reorder --amino --quiet), even after specifying a different algorithm like --localpair [25].

Solution

- Verify Parameter Syntax: Ensure you are using the single-quote syntax for the

--MSA_Paramflag as described above. - Check Parameter Order: Place the algorithm flag (e.g.,

--localpair) before other numerical parameters (e.g.,--maxiterate) to avoid misinterpretation. - Inspect the Output: After correction, check the GUIDANCE2 log files again. A successful run will list your chosen parameters in the MAFFT command.

Problem: Handling Large or Computationally Intensive Alignments

Symptoms The alignment step with MAFFT via GUIDANCE2 takes an extremely long time or fails due to excessive memory usage, especially with many sequences [26].

Solution

- Choose a Faster Algorithm: For datasets with more than 200 sequences, consider using speed-oriented MAFFT methods like

--retree 1or--retree 2within your GUIDANCE2 analysis [24]. - Leverage Multiple Cores: Use the

--threadparameter for MAFFT to utilize multiple processors. This can be specified within the--MSA_Paramstring.- Example:

--MSA_Param '--localpair --thread 8'

- Example:

- Resource Planning: For very large datasets (e.g., >1,000,000 sequences), ensure your computational resources are adequate. MAFFT can be memory-intensive, and GUIDANCE2 runs MAFFT multiple times, multiplying the resource requirements [27] [26].

Problem: Alignment Uncertainty Affecting Bayesian MCMC Convergence

Symptoms Your Bayesian phylogenetic analysis in software like BEAST2 or MrBayes exhibits poor convergence, as indicated by low Effective Sample Sizes (ESS) for parameters, despite lengthy runs [23].

Background Cause Alignment errors create regions of ambiguous homology, which can introduce "model violation" – a situation where the evolutionary model used in the phylogenetic analysis cannot adequately explain the patterns in the data. This creates a complex, multi-modal posterior distribution that is difficult for the MCMC sampler to explore efficiently, leading to poor convergence and unreliable parameter estimates [23] [13].

Solution

- Run GUIDANCE2: First, run your initial MSA through GUIDANCE2 with MAFFT to get column confidence scores (CS).

- Filter the Alignment: Create a filtered version of your alignment by removing columns with a confidence score below a chosen threshold (e.g., 0.6 or 0.93).

- Re-run Phylogenetic Analysis: Perform your Bayesian phylogenetic inference on both the full and filtered alignments.

- Compare Results: Compare the convergence diagnostics (e.g., ESS values) and the resulting phylogenetic trees between the two analyses. Improved convergence and stability in the filtered analysis often indicates that alignment uncertainty was a contributing factor to the initial problem.

The following workflow diagram illustrates this integrated process for robust phylogenetic inference:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Software and Resources for Alignment and Phylogenetics

| Item Name | Type | Function & Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| GUIDANCE2 | Software Package | Quantifies reliability of MSA columns by assessing uncertainty from guide trees, co-optimal alignments, and indel formation [22]. |

| MAFFT | Alignment Algorithm | Produces high-accuracy multiple sequence alignments. Offers a suite of algorithms (e.g., L-INS-i, G-INS-i) for different data types [24]. |

| BEAST2 / MrBayes | Bayesian Phylogenetic Software | Infers time-scaled phylogenies and evolutionary parameters using MCMC. BEAST2 is well-suited for complex models and phylodynamics [23] [13]. |

| Tracer | Diagnostic Tool | Analyzes MCMC output from BEAST2 and other software to assess convergence (ESS) and mixing, crucial for troubleshooting [13]. |

| jModelTest/PartitionFinder | Model Selection Tool | Helps select the best-fit nucleotide substitution model for your data, improving the realism of the phylogenetic model [13]. |

Automated and Robust Evolutionary Model Selection Using ProtTest and MrModeltest

In Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, convergence issues in Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) simulations often stem from an often-overlooked source: incorrect evolutionary model selection. Even with advanced MCMC algorithms and extended run times, analyses using improperly selected substitution models frequently fail to converge on the true posterior distribution or exhibit poor mixing [17] [28]. This technical guide establishes how automated model selection tools—ProtTest for protein sequences and MrModeltest for nucleotide sequences—integrate within a robust phylogenetic workflow to directly address convergence problems. By implementing statistical criteria such as Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), these tools automate the identification of optimal evolutionary models, thereby enhancing the reliability and reproducibility of phylogenetic studies [17]. The following troubleshooting guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with targeted solutions to specific experimental challenges encountered during evolutionary model selection.

Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs for ProtTest and MrModeltest

FAQ 1: Why does my Bayesian analysis in MrBayes fail to converge even with extended run times, and how can model selection address this?

- Issue: Poor MCMC convergence or mixing in MrBayes often results from using an underparameterized or overparameterized evolutionary model. An incorrect model violates MCMC assumptions, leading to unreliable parameter estimates and tree topologies.

- Solution:

- Automate Model Selection: Before executing MrBayes, rigorously determine the best-fit model using ProtTest (for protein sequences) or MrModeltest (for nucleotide sequences). These tools evaluate a suite of candidate models against your specific dataset [17].

- Statistical Criteria: Rely on statistical criteria like AIC or BIC for model selection, which balance model fit with complexity, rather than making arbitrary choices [17].

- Diagnose in Tracer: Use Tracer to visualize MCMC output. If the Effective Sample Size (ESS) for parameters is low (< 200) and trace plots show poor mixing, improper model selection is a likely contributor [28]. Re-initiate the analysis with the model recommended by ProtTest or MrModeltest.

FAQ 2: How do I resolve "Invalid image format" or Java-related errors when running ProtTest?

- Issue: ProtTest is dependent on Java, and errors related to image formats or startup often trace back to Java configuration issues.

- Solution:

- Verify Java Installation: Ensure you have Java 8 or a later version installed correctly on your system. You can check this by running

java -versionin your command-line terminal [17]. - Correct Installation Path: Install ProtTest in a directory whose path contains only English characters and no spaces. Special characters or spaces in the file path can disrupt execution [17].

- Execute from Install Directory: Navigate to the directory where ProtTest is extracted using the command line before executing the ProtTest command.

- Verify Java Installation: Ensure you have Java 8 or a later version installed correctly on your system. You can check this by running

FAQ 3: Why does MrModeltest fail to execute or produce output in PAUP*?

- Issue: MrModeltest operates as a PAUP* block and requires specific execution steps within the PAUP* environment.

- Solution:

- File Placement: Copy the

MrModelblockfile from the MrModeltest package into your working directory that contains your sequence data [17]. - Execution in PAUP: Open your data in PAUP and execute the MrModelblock file via

File > Execute[17]. This will generate an output file (e.g.,mrmodel.scores) containing the model scores for comparison. - Format Compatibility: Ensure your input sequence alignment is in a format compatible with PAUP*, such as the NEXUS format [17].

- File Placement: Copy the

FAQ 4: How do I handle highly incongruent phylogenetic results from large datasets despite using many genes?

- Issue: The mere addition of more sequence data does not guarantee resolution of phylogenetic incongruence. This can be caused by non-phylogenetic signal (e.g., undetected homoplasy) or model violation, where the selected model is a poor fit for the dataset's complexity [29].

- Solution:

- Leverage Site-Heterogeneous Models: For deep evolutionary questions, the standard models evaluated by ProtTest and MrModeltest might be insufficient. Consider employing site-heterogeneous models (e.g., the CAT model in PhyloBayes), which account for varying evolutionary processes across alignment sites and can reduce artifacts like Long Branch Attraction (LBA) [29].

- Explore Model Fit: Use ProtTest and MrModeltest to identify if a more complex model (e.g., with gamma-distributed rate variation and a proportion of invariant sites) is strongly recommended for your data [17].

FAQ 5: What are the steps to take when Tracer indicates convergence problems after using the ProtTest/MrModeltest recommended model?

- Issue: Even with an appropriate model, MCMC analyses can have problems. Tracer might reveal a bimodal posterior distribution, low ESS values, or clearly divergent traces from multiple independent runs [30].

- Solution:

- Run Multiple Replicates: Always perform at least two independent MCMC analyses from different starting points. In Tracer, compare the traces and marginal densities of key parameters (like the posterior) across runs to check for consistency [30].

- Tune MCMC Operators: If a specific parameter (e.g.,

clockRate) has low ESS, increase the weight of its sampling operator in BEAUti to propose new values more frequently [28]. - Add Joint Operators: If parameters are correlated (e.g.,

Tree.heightandclockRateare often negatively correlated), add anUpDownoperator to propose updates to both parameters simultaneously, which can dramatically improve mixing [28].

Experimental Protocols for Key Procedures

Protocol 1: Automated Model Selection and Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis

This protocol provides a systematic workflow from sequence alignment to Bayesian tree estimation, integrating automated model selection to prevent convergence issues [17].

- Software Requirements: Python 3.13.1, JAVA 8+, PAUP*, MEGA X, MrModeltest2, ProtTest 3.4.2, MrBayes 3.2.7a.

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Robust Sequence Alignment:

- Input your multi-sequence data in FASTA format into the GUIDANCE2 server, selecting MAFFT as the alignment tool.

- Execute the alignment and download the resulting alignment file. Use GUIDANCE2 to identify and remove unreliably aligned columns [17].

- Sequence Format Conversion:

- Use MEGA X to convert the aligned FASTA file into a NEXUS format file, which is required by downstream tools [17].

- Optimal Evolutionary Model Selection:

- For Nucleotide Sequences: Execute MrModeltest within PAUP* to compare nucleotide substitution models. The best-fit model is selected based on the lowest AIC/BIC score [17].

- For Protein Sequences: Run ProtTest from its installation directory via the command line. It will evaluate protein evolution models and identify the best model according to AIC/BIC [17].

- Bayesian Phylogenetic Inference:

- Configure your MrBayes analysis block within a NEXUS file. Use the

lsetcommand to apply the model and parameters (e.g.,nst,rates) specified by ProtTest or MrModeltest. - Execute the analysis in MrBayes, running at least two independent MCMC chains and monitoring for convergence [17].

- Configure your MrBayes analysis block within a NEXUS file. Use the

- Validation and Visualization:

- Use Tracer to confirm that ESS values for all parameters are >200 and that trace plots from multiple runs overlap, indicating convergence [28].

- Summarize the posterior tree distribution in MrBayes and visualize the final phylogenetic tree.

- Robust Sequence Alignment:

The workflow for this protocol, which integrates model selection as a core step for ensuring convergence, is outlined in the diagram below.

Protocol 2: Diagnosing MCMC Convergence Problems in Tracer

This protocol offers a detailed methodology for identifying and resolving convergence issues after running a Bayesian phylogenetic analysis [28] [30].

- Software Requirement: Tracer v1.7+

- Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Load Log Files: Open Tracer and import the

.logfiles from two or more independent MCMC runs viaFile > Import Trace Fileor by dragging and dropping the files. - Inspect Effective Sample Size (ESS): In the left-hand panel, check the ESS values for all parameters, especially the posterior. An ESS below 200 indicates insufficient sampling and high autocorrelation [28].

- Examine Trace Plots: Select the

posteriorparameter and navigate to the "Trace" tab. Well-mixed chains should resemble a "hairy caterpillar" and show strong overlap between independent runs. A bimodal distribution or divergent traces between runs indicates a failure to converge on the same posterior distribution [30]. - Compare Marginal Densities: Select the log files for all independent runs (not the combined trace). View the "Marginal Density" tab. The density distributions for each run should overlay closely. Major discrepancies suggest the chains have sampled different distributions.

- Check for Parameter Correlation: Select two parameters (e.g.,

clockRateandTree.height) simultaneously using the Ctrl/Cmd key. Go to the "Joint-Marginal" tab to visualize their correlation. Strong correlation may require adding joint operators (e.g., an UpDown operator) to the analysis [28].

- Load Log Files: Open Tracer and import the

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

Table 1: Key Software Tools for Evolutionary Model Selection and Phylogenetic Analysis

| Tool Name | Category | Primary Function | Role in Solving Convergence Issues |

|---|---|---|---|

| ProtTest 3.4.2 [17] | Model Selection | Automates selection of best-fit protein evolution models using AIC/BIC. | Prevents model violation, a major source of bias and poor MCMC convergence. |

| MrModeltest 2.4 [17] | Model Selection | Automates selection of best-fit nucleotide substitution models using AIC/BIC. | Ensures the nucleotide model complexity matches the data, reducing non-phylogenetic signal. |

| MrBayes 3.2.7a [17] | Phylogenetic Inference | Performs Bayesian phylogenetic analysis using MCMC sampling. | Its operators can be tuned based on convergence diagnostics to improve mixing. |

| Tracer 1.7 [28] [30] | Diagnostics | Visualizes MCMC output, calculates ESS, and assesses convergence. | The primary tool for diagnosing convergence problems and verifying solution efficacy. |

| GUIDANCE2 [17] | Alignment | Performs robust sequence alignment and identifies unreliable regions. | Reduces alignment uncertainty that can introduce error and hinder convergence. |

| PAUP* [17] | Phylogenetic Analysis | A versatile tool for phylogenetic analysis; used to execute MrModeltest. | Provides the environment for model testing and data format handling. |

| BEAUti/BEAST2 [28] | Phylogenetic Inference | Suite for Bayesian evolutionary analysis; used in illustrative examples. | Allows detailed configuration of MCMC operators to resolve mixing issues. |

Workflow Diagram: Integrated Strategy for Resolving Convergence Issues

The following diagram synthesizes the troubleshooting and diagnostic procedures into a single, coherent strategy for resolving MCMC convergence problems, emphasizing the central role of model selection.

By systematically implementing the automated model selection protocols and troubleshooting guides outlined above, researchers can directly address and resolve the convergence issues that frequently impede Bayesian phylogenetic analysis, leading to more reliable and reproducible evolutionary inferences.

A technical guide to advanced MCMC techniques for Bayesian phylogenetics

Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC) is a powerful Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) method that uses gradient information to propose more efficient transitions through the parameter space, often leading to faster convergence and better sampling efficiency compared to traditional random-walk algorithms [31] [32]. While HMC and its advanced variant, the No-U-Turn Sampler (NUTS), are implemented in probabilistic programming frameworks like Stan [31] [32], their direct availability within the standard installation of BEAST 2 for Bayesian phylogenetic analysis is limited. This guide addresses convergence issues by exploring the advanced samplers that are available in BEAST and provides protocols for their effective use.

Is Native HMC Available in BEAST?

As of the latest information, the core BEAST 2 package does not natively implement Hamiltonian Monte Carlo (HMC). The primary MCMC engine in BEAST 2 relies on a suite of operators that use traditional proposal mechanisms [33] [28] [34].

However, BEAST 2 offers a powerful alternative for tackling complex sampling problems: Metropolis-Coupled MCMC (MC³), also known as parallel tempering [35].

How to Use Metropolis-Coupled MCMC (MC³) in BEAST 2

MC³ runs multiple chains in parallel, each at a different "temperature". Heated chains can traverse rugged likelihood landscapes more easily, escaping local optima and helping the main "cold" chain converge more effectively [35]. It has been shown to solve convergence problems where standard MCMC fails and can improve the Effective Sample Size (ESS) per unit of computational time [35].

Implementation Protocol:

You can set up an MC³ analysis in BEAST 2 via the CoupledMCMC package.

- Install the Package: First, ensure the

CoupledMCMCpackage is installed in BEAST 2. - Using BEAUti:

- Open BEAUti.

- Navigate to

File > Templatesand select theCoupledMCMCtemplate. This configures your analysis to use MC³ by default [35].

- Convert an Existing XML:

- Use the

MCMC2CoupledMCMCapplication, available after installing the package. - Either run it via the command line:

/path/to/beast/bin/applauncher MCMC2CoupledMCMC -xml mcmc.xml -o mc3.xml - Or through BEAUti's

File > Launch appsmenu [35].

- Use the

- Key Configuration Parameters: When setting up MC³, you will encounter several parameters [35]:

chains: The number of parallel chains (default is 2).deltaTemperatureortarget: The temperature difference between chains or the target acceptance probability for swaps (default is 0.234).optimise: If set totrue, the temperature scheme is automatically optimized.

The following workflow summarizes the process of implementing and troubleshooting an MCMC analysis in BEAST:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The table below lists key software and diagnostic tools essential for conducting and troubleshooting advanced MCMC analyses in phylogenetics.

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Key Use-Case in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|---|

| BEAST 2 [33] [28] | Bayesian evolutionary analysis using MCMC. | Core software for performing phylogenetic inference. |

| BEAUti 2 [33] [28] | Graphical utility for generating BEAST XML configuration files. | Setting up models, priors, and MCMC operators; enabling MC³ via templates [35]. |

| Tracer [33] [28] [30] | Visualization and analysis of MCMC output. | Calculating Effective Sample Size (ESS), inspecting trace plots, and diagnosing convergence issues. |

| CoupledMCMC Package [35] | Implements Metropolis-Coupled MCMC (MC³) in BEAST 2. | Enabling parallel tempering to escape local optima and improve mixing. |

Tuning MCMC Performance: A Quantitative Guide

For standard MCMC, performance is highly dependent on the operators and their weights. The table below summarizes actionable strategies based on specific symptoms observed in Tracer. The goal for most continuous parameters is an ESS > 200 and an operator acceptance rate near 0.234 (23.4%) for optimal efficiency [34].

| Observed Symptom | Diagnostic Method | Recommended Action | Expected Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low ESS for all parameters [33] [28] | Check ESS values for every parameter in Tracer. | Increase the chain length (chainLength in the MCMC panel). |

Higher ESS values across all parameters. |

| Low ESS for one specific parameter [33] [28] | Check the trace plot for a specific, poorly-mixing parameter. | Increase the weight of that parameter's operator in BEAUti's "Operators" panel. | Improved mixing and higher ESS for the target parameter. |

| Parameters are highly correlated [33] [28] | Use Tracer's "Joint-Marginal" plot to visualize parameter pairs. | Add or increase the weight of an UpDown operator that updates the correlated parameters together. |

More efficient exploration of the joint parameter space, improving overall mixing. |

| Chains trapped in local optima [35] [30] | Run multiple independent MCMC runs and compare posterior distributions in Tracer. | Use the Metropolis-Coupled MCMC (MC³) method. | Heated chains help the cold chain explore the posterior more fully, aiding convergence. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My analysis has been running for a long time but the ESS for some parameters is still low. What should I do? This indicates poor mixing. First, use Tracer to identify which parameters have low ESS. If it's one or two parameters, try increasing their operator weights. If many parameters are affected, or if you suspect complex correlations, consider switching to an MC³ analysis, which is often the most robust solution for difficult sampling problems [35].

Q2: How can I check if my MCMC run has converged? Convergence should never be assessed from a single chain. The best practice is to run at least two independent analyses from different starting points. In Tracer, select the trace files from both runs. If the traces for all parameters, especially the posterior, overlay well and the estimated marginal distributions look identical, it is a good sign of convergence [30].

Q3: Are there other advanced models in BEAST that might affect MCMC performance? Yes. Using more complex models like Markov-modulated substitution models can significantly increase the dimensionality of the parameter space and computational cost, potentially exacerbating convergence issues [36]. In such cases, leveraging BEAGLE libraries for GPU computing and carefully following setup tutorials is crucial.

FAQs: Subtree Prune-and-Regraft (SPR) Moves

Q1: What is an SPR move and why is it fundamental to phylogenetic tree search?

An SPR (Subtree Prune-and-Regraft) move is a topological rearrangement operation used to explore different phylogenetic tree structures. It works by selectively cutting a subtree from the main tree (pruning) and then reinserting it at a different branch (regrafting). This operation is a core component of phylogenetic search algorithms in both maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference because it enables a thorough exploration of tree space, helping to avoid local optima and move toward the best tree given the data [37]. Its efficiency is critical, as performing SPR moves more intelligently can drastically reduce the computational time required to find an optimal tree [38].

Q2: How can poor SPR move proposals lead to MCMC convergence issues in Bayesian phylogenetics?

In Bayesian phylogenetic inference using Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), the sampler must adequately explore the posterior distribution of trees. If SPR moves are inefficient—for instance, if they frequently propose new trees that are rejected—the chain can fail to converge. This means the MCMC run may not be representative of the true posterior distribution, leading to unreliable phylogenetic estimates and branch support. Therefore, assessing topological convergence, and not just parameter convergence, is essential for robust analysis [15].

Q3: What strategies can improve the efficiency of SPR moves?

Key strategies involve filtering out less promising moves before performing computationally expensive likelihood calculations. Research has demonstrated two effective methods:

- Distance-Based Filtering: A fast distance-based method can identify and discard the least promising candidate SPR moves.

- Local Likelihood Estimation: Instead of evaluating the likelihood of the entire tree for every possible move, the change in likelihood is estimated locally for the remaining potential SPRs. Implementing a sophisticated filtering strategy that combines these approaches allows the algorithm to concentrate most of the computational effort on the most promising rearrangement moves, significantly improving efficiency [38].

Q4: What is the difference between rSPR and uSPR?

The application of SPR moves depends on whether the tree is rooted or unrooted:

- rSPR (Rooted SPR): Applied to rooted trees. The procedure involves breaking any edge except the one leading to the root node. The end of the edge that is furthest from the root is then attached to any other edge in the tree.

- uSPR (Unrooted SPR): Applied to unrooted trees. The procedure involves breaking any edge. One end of this edge (selected arbitrarily) is then connected to any other edge in the tree [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor MCMC Mixing and Convergence

Symptoms

- Low Effective Sample Size (ESS) values for tree-related parameters (e.g., Tree Likelihood, Tree Length) in Bayesian software output.

- Trace plots of the log-likelihood or other parameters that do not look like "fuzzy caterpillars," but instead show strong trends or get stuck.

- Significant disagreement in consensus trees or posterior clade probabilities between multiple, independent MCMC runs [15].

Solutions

- Run Multiple Independent Analyses: Always perform at least two MCMC runs from different starting trees. This allows you to directly assess whether the chains have converged on the same distribution of trees [15].

- Adjust the SPR Tuning Parameter: Bayesian software like MrBayes often has a tuning parameter that controls the size of SPR moves. If the acceptance rate for new trees is very low, try reducing the step size of the SPR move. If the acceptance rate is very high but mixing is poor, cautiously increase the step size to propose larger jumps in tree space.

- Use Topological Convergence Diagnostics: Go beyond continuous parameter diagnostics. Use tools designed to assess convergence in tree topology, such as comparing consensus trees from independent runs or calculating the frequency of clades across runs [15].

- Combine with Local Moves: Supplement wide-ranging SPR moves with more local rearrangements like Nearest Neighbor Interchange (NNI). This hybrid strategy can sometimes help refine areas of the tree more efficiently, reducing the time to find good solutions [38].

Problem 2: Excessive Computational Time for Tree Search

Symptoms

- Phylogenetic analysis takes impractically long to complete, even for datasets of moderate size (e.g., 50-100 taxa).

Solutions

- Implement Efficient SPR Algorithms: Use software that incorporates advanced SPR algorithms. These algorithms use filtering strategies to avoid calculating the likelihood for every possible SPR move, focusing computation only on the most promising candidates [38].

- Validate Your Alignment and Model: A poor sequence alignment or an incorrect substitution model can make the tree search landscape more complex and difficult to navigate. Use tools like GUIDANCE2 for robust alignment and ProtTest/MrModeltest for model selection to ensure a solid foundation for the analysis [17].

- Check Hardware and Parallelization: Ensure you are using a compiled version of the software that can leverage multiple CPU cores. Some programs can parallelize likelihood calculations across cores, significantly speeding up the evaluation of proposed trees.

Problem 3: Algorithm Trapped in Local Optima

Symptoms

- The log-likelihood or model score plateaus at a value that is lower than expected.

- The tree topology does not improve despite long runtimes.

Solutions

- Use Sectorial Searches or Tree Drifting: Some algorithms allow for a "sectorial search," where a part of the tree is detached and optimized more intensively before being reinserted. "Tree drifting," which incorporates a simulated annealing approach, can also help the search escape local optima by occasionally accepting less optimal trees [37].

- Leverage Tree Fusing: If multiple independent searches find different trees of similar quality, tree fusing can be employed. This method combines well-supported subtrees from different analyses to create a new, potentially better tree [37].

- Start from a Better Tree: If possible, initiate the search from a tree constructed using a fast and robust method (e.g., maximum likelihood with a simple model) rather than from a random tree. This can provide a better starting point in the tree space [38].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Efficient SPR Move Evaluation Protocol

The following methodology outlines the steps for implementing an efficient SPR-based tree search, as informed by research on improving SPR efficiency [38].

- Generate Candidate Moves: For the current tree, generate a comprehensive list of all possible SPR moves within a defined radius or without constraint.

- Apply Distance-Based Filtering: Use a fast, distance-based metric to quickly evaluate all candidate moves. Discard those moves that are identified as least promising based on this preliminary filter.

- Perform Local Likelihood Estimation: For the remaining, filtered set of candidate SPR moves, calculate a local estimate of the change in likelihood. This avoids the computational cost of a full tree likelihood calculation at this stage.

- Rank and Select Top Moves: Rank the candidate moves based on their local likelihood score. Select the top k moves for full evaluation.

- Full Likelihood Evaluation and Acceptance: Perform a full, global likelihood calculation for the tree resulting from each of the top k moves. Accept or reject the proposed new tree based on the relevant criterion (e.g., likelihood improvement in a hill-climbing search, or Metropolis-Hastings ratio in an MCMC sampler).

Quantitative Comparison of Tree Rearrangement Moves

The table below summarizes the characteristics of different basic tree rearrangement operations, which help contextualize the role of SPR moves [37].

Table 1: Comparison of Basic Tree Rearrangement Moves

| Move Type | Full Name | Scope of Change | Computational Intensity | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NNI | Nearest-Neighbor Interchange | Very Local | Low | Fastest; explores minimal changes by swapping two adjacent subtrees. |

| SPR | Subtree Prune-and-Regraft | Intermediate | Medium | More extensive search than NNI; moves entire subtrees to new locations. |

| TBR | Tree Bisection and Reconnection | Wide/Global | High | Most extensive; severs a branch and tries all possible reconnections. |

Workflow Visualization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Tools for Bayesian Phylogenetic Analysis

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Relevant Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| MrBayes | Software for Bayesian phylogenetic inference using MCMC. | Executing the core Bayesian analysis, including SPR moves, to estimate the posterior distribution of trees [17]. |

| GUIDANCE2 | Evaluates sequence alignment reliability and removes unreliable regions. | Creating a robust multiple sequence alignment, which is the critical foundation for an accurate tree search [17]. |

| ProtTest / MrModeltest | Automates the selection of the best-fit evolutionary model using statistical criteria (AIC/BIC). | Choosing the correct nucleotide or protein substitution model to ensure the analysis's assumptions are met [17]. |

| MAFFT | Performs multiple sequence alignment. | Often used in conjunction with GUIDANCE2 to generate the initial alignments [17]. |

| PAUP* | A versatile program for phylogenetic analysis with support for various methods and formats. | Useful for data format conversion and performing preliminary analyses [17]. |

A Step-by-Step Diagnostic and Troubleshooting Protocol for Convergence Issues

Why is assessing topological convergence specifically important?

In Bayesian phylogenetic inference, standard convergence diagnostics like Effective Sample Size (ESS) and trace plots are designed for continuous parameters and are incompatible with the tree topology, which is a crucial parameter of the analysis [39]. Relying solely on these standard metrics can be misleading, as an analysis might appear converged for all continuous parameters while the chains have not adequately explored the distribution of tree topologies. Assessing topological convergence is therefore a separate, essential step for validating the reliability of your inferred phylogeny [39].

How do I perform multiple independent MCMC runs?

The following workflow ensures a rigorous assessment of topological convergence.

Detailed Methodology:

- Independent Replicates: Run at least two, but preferably more, independent MCMC analyses. Each run must:

- Check Standard Diagnostics First: Before assessing topological mixing, use a tool like Tracer to verify that the ESS for all continuous parameters (e.g., posterior, likelihood, clock rate, substitution rates) is sufficiently high (typically >200) and that trace plots look like "hairy caterpillars," indicating good mixing [33].

- Assess Topological Convergence: Use specialized tools to compare the tree samples from your independent runs. The RWTY (R We There Yet) R package is designed for this purpose and provides several diagnostic functions [40].

What are the key diagnostics for topological mixing?

The table below summarizes the primary diagnostics and their interpretation.

| Diagnostic Method | Description | Interpretation of Good Convergence |

|---|---|---|

| ASDSF (Average Standard Deviation of Split Frequencies) | Measures the standard deviation of split (clade) frequencies across runs. | An ASDSF value below 0.01 is a good indicator that topological convergence has been achieved [39]. |

| Tree Topology ESS | An Effective Sample Size calculated for tree topologies, often based on the frequency of splits or a topological distance. | The ESS should be sufficiently high (e.g., >200), indicating an adequate number of independent samples from the posterior distribution of trees [40]. |

| PCoA (Principal Coordinates Analysis) Plots | Visualizes the similarity of tree samples from different runs in a reduced topological space. | Tree samples from all independent runs should form a single, overlapping cloud, showing they are sampling the same region of tree space [39] [40]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

The following software tools are essential for implementing this protocol.

| Item Name | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|

| BEAST2 / BEAST X | The core software platform for performing Bayesian phylogenetic, phylogeographic, and phylodynamic inference via MCMC sampling [33] [41]. |

| RWTY (R We There Yet) | An R package that provides a convenient interface for multiple phylogenetic MCMC convergence diagnostics, with a strong focus on assessing topological mixing [40]. |

| Tracer | A visualization tool for analyzing trace files from MCMC runs. It is essential for assessing the convergence and mixing of continuous model parameters [33]. |

What if my replicates show topological disagreement?

If your independent runs fail to converge on a similar set of topologies, consider these troubleshooting steps:

- Increase MCMC Chain Length: The simplest solution is to run your analyses for more iterations. This gives the chains more time to adequately explore the complex tree space [33].

- Tune MCMC Operators (in BEAST2): Improve the efficiency of the MCMC sampler by adjusting its proposal mechanisms. You can increase the operating frequency (weight) of operators for poorly mixing parameters or add specialized operators, like an UpDown operator, to handle correlated parameters (e.g., clock rate and tree height) more effectively [33].

- Re-evaluate Model Specification: An overly complex model for your data can lead to convergence problems. Consider simplifying your substitution, clock, or tree models.

FAQs: Understanding Topological ESS