Solving Low Sequencing Complexity in ChIP-seq: A Modern Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Solutions

Low sequencing complexity in ChIP-seq experiments remains a significant challenge, leading to high background noise, inefficient sequencing, and compromised data quality.

Solving Low Sequencing Complexity in ChIP-seq: A Modern Guide from Foundational Concepts to Advanced Solutions

Abstract

Low sequencing complexity in ChIP-seq experiments remains a significant challenge, leading to high background noise, inefficient sequencing, and compromised data quality. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals, addressing this issue from foundational principles to cutting-edge solutions. We explore the core mechanisms behind low complexity, evaluate modern enzymatic methods like CUT&Tag and CUT&RUN that offer inherent improvements, and deliver a practical troubleshooting framework for optimizing traditional ChIP-seq protocols. Finally, we establish a rigorous validation and benchmarking strategy, incorporating AI-powered bioinformatics tools, to ensure the generation of high-fidelity, publication-ready data for robust biomedical and clinical research.

Understanding the Root Causes: What is Low Sequencing Complexity and Why Does It Plague ChIP-seq Data?

Defining Low Sequencing Complexity in the Context of ChIP-seq

FAQs on Low Sequencing Complexity in ChIP-seq

What is sequencing complexity in ChIP-seq? Sequencing complexity refers to the proportion of unique DNA fragments in your sequenced library compared to the total number of sequenced reads. A high-complexity library contains mostly unique genomic regions, while a low-complexity library is dominated by PCR duplicates—multiple reads representing the same original DNA fragment [1] [2].

Why is low complexity a problem? Low-complexity libraries can severely distort your biological interpretation. They often lead to:

- Increased false positives: The same few DNA fragments are sequenced repeatedly, creating artificial "peaks" that do not represent true protein-DNA binding [3] [4].

- Reduced sensitivity: The substantial number of unique DNA fragments is low, meaning you lose the statistical power to detect weaker, yet biologically important, binding events [1].

- Wasted resources: Interpreting data from a failed experiment can lead to incorrect conclusions and futile follow-up experiments [5].

How is library complexity measured? The ENCODE Consortium recommends specific metrics for assessing library complexity, which are calculated from your aligned sequencing data (BAM files) [2]:

Table 1: Key Metrics for Assessing ChIP-seq Library Complexity

| Metric | Full Name | Calculation | Preferred Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| NRF | Non-Redundant Fraction | ( N{nonred} / N{all} ) | > 0.9 [2] |

| PBC1 | PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 1 | ( N{unique} / N{all} ) | > 0.9 [2] |

| PBC2 | PCR Bottlenecking Coefficient 2 | ( N{unique} / N{nonred} ) | > 10 [2] |

( N_{all} ): Total number of mapped reads. ( N_{nonred} ): Number of non-redundant, uniquely mapped reads. ( N_{unique} ): Number of genomic locations to which exactly one unique read maps [2].

A library with an NRF < 0.8 for 10 million reads is considered to have low complexity, and datasets falling below this threshold are often flagged as potential failures [1] [2].

What are the main wet-lab causes of low complexity? Low complexity typically stems from issues early in the ChIP protocol that result in an insufficient amount of unique DNA before PCR amplification:

- Insufficient starting material: Beginning with too few cells is a primary cause, as there are simply not enough original DNA fragments [1] [6].

- Overly stringent PCR amplification: Excessive PCR cycles are used to generate a sequencer-ready library from a small amount of DNA, leading to over-amplification of the few available unique fragments [4].

- Suboptimal chromatin immunoprecipitation: A failed or inefficient IP, due to a low-affinity antibody or poor protocol, yields very little precipitated DNA [6] [7].

- Sample degradation: If the chromatin is degraded during preparation, the number of viable DNA templates is reduced [6] [7].

Table 2: Troubleshooting Common Wet-Lab Causes of Low Complexity

| Problem | Possible Solution |

|---|---|

| Insufficient starting cells | Increase cell numbers; for rare cells, use low-input protocols like HT-ChIPmentation [8]. |

| Inefficient immunoprecipitation | Use a ChIP-validated antibody; optimize antibody amount and incubation time [6] [7]. |

| Poor chromatin shearing/fragmentation | Optimize sonication parameters or MNase concentration to achieve 200-500 bp fragments [6]. |

| Sample degradation | Perform all steps on ice or at 4°C; include protease inhibitors in buffers [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for High-Complexity ChIP-seq Libraries

| Reagent / Material | Function | Considerations for Quality |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-validated Antibody | Specifically immunoprecipitates the target protein or histone modification. | Must be validated for ChIP. Check for lot-specific certification [9] [4]. |

| Magnetic Beads (Protein A/G) | Captures antibody-target complexes for purification. | Use magnetic beads to reduce non-specific binding [9] [7]. |

| Protease Inhibitors | Prevents degradation of proteins and chromatin during processing. | Essential for maintaining sample integrity. Use EDTA-free versions if needed for later steps [9]. |

| High-Fidelity PCR Enzymes | Amplifies the library for sequencing with minimal bias. | Reduces PCR artifacts during library amplification [4]. |

| Tn5 Transposase (for Tagmentation) | Simultaneously fragments DNA and adds sequencing adapters. | Used in modern protocols like HT-ChIPmentation to improve efficiency and reduce hands-on time [8]. |

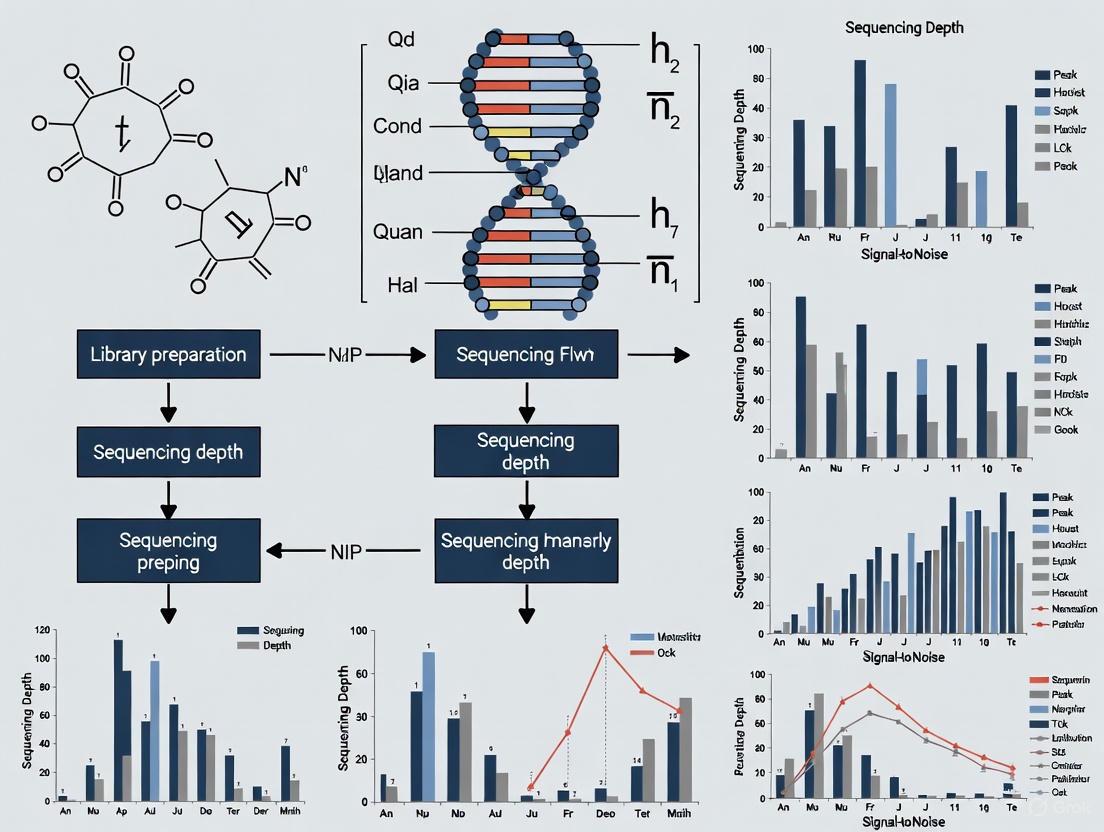

Workflow Diagram for Diagnosing and Addressing Low Complexity

The following diagram illustrates a logical workflow for identifying the causes of low sequencing complexity and selecting the appropriate remedial actions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are the most common causes of high background in ChIP-seq data? High background often stems from antibody-related issues, such as cross-reactivity or non-specific binding, or from suboptimal library preparation leading to over-amplification of low-complexity samples [10] [11]. Using an insufficient number of cells for the target's abundance can also worsen the signal-to-noise ratio [10].

My sequencing depth seems adequate, but the peaks look weak. What could be wrong? Sequencing depth is only one factor. A low Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) is a more direct indicator of poor signal-to-noise. Even with many reads, if a small percentage fall in enriched regions, your effective signal is low. This can be caused by a failed immunoprecipitation, a low-quality antibody, or a high-background control that skews peak calling [11] [12].

How can I tell if my antibody is the source of the problem? A primary test is to check the antibody's specificity via immunoblot. A good antibody should show a single major band at the expected molecular weight, containing at least 50% of the signal on the blot [11]. The most definitive control is to perform the ChIP-seq experiment in a knockout or knockdown model of your target; any remaining peaks are likely due to antibody cross-reactivity [10] [11].

What is an acceptable duplicate rate for a ChIP-seq library? It depends on the sequencing depth and the target. However, a very high duplicate rate (e.g., over 50%) can be a red flag for low library complexity, indicating over-amplification during PCR or an extremely limited number of true binding sites [12]. In such cases, the unique read count may be too low for reliable analysis.

Key Indicators of Data Quality Issues

The first step in troubleshooting is recognizing the symptoms of high background and low signal-to-noise in your data. The following table summarizes the key metrics to evaluate.

| Indicator | Description | What to Look For |

|---|---|---|

| Low Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP) | Percentage of all mapped reads that fall within called peak regions; a primary metric for signal-to-noise [13]. | Concerning: FRiP < 1% for transcription factors, < 10% for broad histone marks. Ideal: FRiP > 1-5% for TFs, > 20-30% for strong histone marks. |

| High Duplicate Rate | Percentage of reads that are exact duplicates based on their genomic coordinates [14]. | Concerning: >50% for a transcription factor ChIP; suggests low complexity and over-amplification. Note: Some duplication is expected in deeply sequenced experiments. |

| Low Alignment Rate | Percentage of sequenced reads that map uniquely to the reference genome [14]. | Concerning: < 70% uniquely mapped reads. Ideal: > 70-80% uniquely mapped reads. |

| Poor Strand Cross-Correlation | Measures the periodicity of reads centered around binding sites [13]. | Concerning: Low correlation. Ideal: High normalized strand coefficient (NSC) and low relative strand correlation (RSC). |

| Abnormal GC Content | Distribution of guanine-cytosine content in the ChIP sample compared to the reference genome [12]. | Concerning: A non-Gaussian, skewed distribution in the ChIP sample that differs significantly from the input control. |

| Weak Enrichment in ChIP-PCR | Fold-enrichment of known positive genomic regions versus negative control regions before sequencing [10]. | Concerning: < 5-fold enrichment in a standard ChIP-PCR validation test. |

A Workflow for Systematic Diagnosis

Follow this step-by-step guide to diagnose the root cause of quality issues in your ChIP-seq experiment. The diagram below outlines the logical troubleshooting path.

Step 1: Calculate and Interpret the FRiP Score

The FRiP score is the most direct metric for assessing signal-to-noise.

- Action: After peak calling, calculate the number of reads falling inside peaks divided by the total mapped reads.

- Interpretation: A low FRiP score confirms a low signal-to-noise ratio and directs you to investigate the wet-lab and preparation phases of your experiment [13].

Step 2: Verify Pre-sequencing Enrichment

Before devoting resources to sequencing, a simple ChIP-PCR validation is a critical checkpoint.

- Action: Perform qPCR on your immunoprecipitated DNA using primers for several known positive sites and negative control regions.

- Interpretation: If you do not observe at least a 5-fold enrichment at positive sites compared to negative controls, the issue almost certainly lies with the immunoprecipitation itself, not the sequencing [10].

Step 3: Investigate Library Complexity

If pre-sequencing enrichment was good but the FRiP score is low, the problem likely arose during library preparation.

- Action: Check the duplicate rate and GC content in your FastQC reports.

- Interpretation: A high duplicate rate (e.g., >50%) coupled with a low number of unique reads indicates low library complexity, often due to excessive PCR amplification [12]. This creates a background that drowns out true signal.

Research Reagent Solutions and Protocols

Addressing data quality issues often requires optimizing key reagents and protocols. The table below lists essential materials and their roles in ensuring a successful ChIP-seq experiment.

| Reagent / Material | Function | Best Practices & Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Antibody | Binds and enriches the target protein-DNA complex. | Specificity is paramount. Validate by immunoblot (single band) or knockout control [10] [11]. For unstable epitopes or lacking antibodies, consider tagged (e.g., FLAG, HA) or biotinylated approaches [10]. |

| Cells | Source of chromatin for the experiment. | Use sufficient cell numbers: 1-10 million [10]. Use more cells (e.g., 10 million) for low-abundance transcription factors and fewer (e.g., 1 million) for abundant targets like Pol II or H3K4me3. |

| Control Input DNA | Sonicated, non-immunoprecipitated genomic DNA. | This is the preferred control for peak calling as it accounts for biases in chromatin fragmentation and base composition [10]. |

| Chromatin Fragmentation Reagents | Shears DNA to manageable sizes (150-300 bp). | Sonication is standard for cross-linked TF ChIP. MNase digestion is preferred for histone marks on stable nucleosomes. Optimize time/settings to avoid over- or under-sonication [10]. |

| Library Prep Kit | Prepares immunoprecipitated DNA for sequencing. | If library complexity is low, reduce the number of PCR amplification cycles. Use dedicated low-input protocols if starting with limited cell numbers [10]. |

Methodologies for Key Validation Experiments

Protocol 1: Validating Antibody Specificity by Immunoblot

A crucial step before ChIP to ensure your antibody recognizes the intended target.

- Prepare protein extracts from whole cells, nuclei, or a chromatin fraction.

- Perform a western blot with the ChIP antibody.

- Interpret results: The antibody is suitable if a single major band constitutes >50% of the signal and is at the expected molecular weight. Multiple bands or smearing indicate cross-reactivity [11].

Protocol 2: Controlling for Antibody Cross-reactivity with Knockout Cells

The most rigorous control for antibody specificity in the ChIP-seq context.

- Obtain a knockout or knockdown model (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9, RNAi) for your target protein.

- Perform ChIP-seq in parallel on wild-type and knockout cells.

- Analyze the data: Any peaks called in the knockout sample are artifacts from antibody cross-reactivity and should be filtered out from the wild-type dataset [10] [11].

Protocol 3: Optimizing Chromatin Shearing for High Resolution

Proper fragmentation is key to obtaining high-resolution binding sites.

- For Transcription Factors: Use formaldehyde cross-linking followed by sonication in SDS-containing buffers to shear chromatin to 150-300 bp fragments. This preserves transient TF-DNA interactions [10].

- For Histone Modifications: MNase digestion of native chromatin without cross-linking is often preferred. It generates mononucleosome-sized fragments, providing high-resolution data for nucleosome-bound marks [10].

In Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), sequencing complexity refers to the proportion of unique DNA fragments in a sequencing library that provide meaningful biological information. Low-complexity libraries are dominated by PCR duplicates—multiple reads originating from the same original DNA fragment—which waste sequencing depth and reduce the effective resolution of the experiment [4]. This problem frequently stems from technical errors during three critical procedural steps: cross-linking, chromatin sonication, and immunoprecipitation with non-specific antibodies. When these steps are suboptimal, the initial yield of immunoprecipitated DNA is low, requiring excessive amplification that amplifies stochastic noise and artifacts, ultimately compromising data quality and leading to inaccurate biological conclusions [15]. This guide details how these technical culprits introduce bias and provides targeted troubleshooting strategies to restore data integrity.

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving Key Issues

Cross-Linking: The Critical First Step

Problem: Improper cross-linking is a primary source of low yield and subsequent complexity loss. Under-crosslinking fails to preserve transient protein-DNA interactions, leading to poor yield. Over-crosslinking masks antibody epitopes and makes chromatin difficult to shear, also resulting in low yield and poor fragmentation [16] [17].

| Problem | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Over-crosslinking | Masked epitopes, difficult chromatin shearing, high background | Reduce formaldehyde fixation time; ensure fresh preparation of formaldehyde; quench thoroughly with glycine [18] [17]. |

| Under-crosslinking | Poor yield of target protein-DNA complexes, loss of transient interactions | Increase cross-linking time; for indirect interactors, use a two-step protocol (e.g., DSG followed by formaldehyde) [19] [20]. |

| Inefficient Reverse Cross-linking | Low DNA recovery after IP | Increase incubation time at 95°C or use Proteinase K treatment for several hours at 62°C [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Two-Step Cross-Linking for Challenging Targets For transcription factors or co-activators that interact indirectly with DNA, a single formaldehyde cross-link may be insufficient. This protocol uses Disuccinimidyl Glutarate (DSG) followed by formaldehyde [19].

- Cell Preparation: Wash cells with PBS at room temperature three times.

- Protein-Protein Cross-linking: Add 2 mM DSG (freshly prepared in DMSO) in PBS/MgCl₂. Incubate at room temperature for 45 minutes.

- Washing: Wash cells with PBS three times to remove residual DSG.

- Protein-DNA Cross-linking: Add 1% Formaldehyde in PBS. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes.

- Quenching: Quench the reaction by adding glycine to a final concentration of 125 mM and incubating for 5 minutes [18] [19].

- Cell Pellet: Wash cells twice with ice-cold PBS. The pellet can now be used immediately or stored at -80°C.

Chromatin Sonication: Achieving Optimal Fragmentation

Problem: Inefficient sonication directly causes low complexity. Under-sonication yields large DNA fragments that do not solubilize or immunoprecipitate efficiently, while over-sonication can damage chromatin and destroy protein epitopes [16]. Both scenarios reduce the amount of usable DNA, necessitating excessive PCR amplification.

| Problem | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Under-shearing | Low signal, poor resolution, large fragment size (>1000 bp) | Increase sonication repetitions or power; cross-link for a shorter time; use fewer cells [16]. |

| Over-shearing | Low signal, fragment sizes too small (<150 bp), degraded chromatin | Reduce sonication repetitions or power; ensure samples are kept on ice between sonication bursts [21] [16]. |

| Foaming | Sample degradation and protein denaturation | Sonicate samples in small volumes (≤400 µL) in 1.7 mL tubes; keep the sonicator tip close to the bottom of the tube [16]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sonication Optimization Sonication must be empirically determined for each cell type and experimental condition [22].

- Cross-link and Lyse: Cross-link and lyse a small batch of cells as planned for your experiment.

- Aliquot: Divide the lysate into several identical aliquots.

- Time Course: Subject each aliquot to a different number of sonication pulses (e.g., 5, 10, 15, 20 pulses).

- Reverse Cross-linking: For each aliquot, reverse the cross-links and purify the DNA.

- Analysis: Analyze the purified DNA by gel electrophoresis (e.g., Agilent Bioanalyzer). The ideal sonication condition produces a smear of fragments centered between 200-500 bp for transcription factors or 150-300 bp for histone marks [18].

- Apply Conditions: Use the optimized condition for your full-scale ChIP experiment.

Non-Specific Antibody Binding: The Core of Specificity

Problem: Antibodies with low specificity or affinity are a major contributor to high background and low signal-to-noise ratios. This results in the immunoprecipitation of non-target DNA, which, when sequenced, produces a complex but biologically irrelevant background that dilutes the true signal and forces deeper, often futile, sequencing to find true peaks [4] [17].

| Problem | Symptom | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background (Noise) | High amplification in "no antibody" control; low FRiP score | Pre-clear lysate with protein A/G beads; use fresh buffers; increase wash stringency (e.g., use LiCl wash buffer); titrate antibody to optimal concentration [21] [16]. |

| Low Signal | Few or weak peaks despite good sequencing depth | Use ChIP-validated antibody; increase antibody amount; verify antibody subclass compatibility with Protein A/G beads [21] [17]. |

| Antibody Cross-reactivity | Peaks at biologically implausible loci; failure of motif analysis | Characterize antibody specificity by immunoblot or peptide binding assays prior to ChIP; use recombinant monoclonal antibodies for higher specificity [4] [17]. |

Experimental Protocol: Antibody Validation and Use The ENCODE consortium recommends stringent antibody validation standards [4].

- Primary Characterization: Perform immunoblotting to confirm the antibody recognizes a protein of the correct molecular weight.

- Secondary Characterization:

- For transcription factors: Use knockdown (RNAi or mutant) cells to show loss of ChIP signal.

- For histone modifications: Perform peptide-binding assays (ELISA) to ensure the antibody does not cross-react with similar modifications (e.g., H3K9me2 vs. H3K9me3) [17].

- ChIP-QC: After immunoprecipitation, calculate the Fraction of Reads in Peaks (FRiP). A FRiP score greater than 1% is a recommended minimum indicator of a successful experiment [4].

FAQs: Addressing Common Concerns

Q1: My ChIP-seq data has low complexity despite high sequencing depth. What is the most likely cause? The most common cause is a low yield of specific immunoprecipitated DNA fragments, often due to over-crosslinking, under-sonication, or a non-specific antibody. This low starting material requires excessive PCR amplification during library preparation, leading to a high duplicate rate. Focus on optimizing these three steps to increase your specific yield [15].

Q2: How can I improve my ChIP-seq results when working with limited cell numbers? Standard ChIP requires ~1-10 million cells, but low-input protocols exist. Techniques like linear amplification (LinDA) or nano-ChIP-seq have been successfully used with 5,000-10,000 cells. These methods use specialized library preparation kits (e.g., Accel-NGS 2S, ThruPLEX) designed to minimize bias when amplifying tiny amounts of DNA [4] [15].

Q3: My antibody works perfectly for Western blot. Why does it fail in ChIP? ChIP is a more demanding application. The antibody must recognize its target in the context of cross-linked, chromatinized proteins where the epitope may be buried or altered. An antibody that works in Western blot may not recognize the native, cross-linked epitope. Always use an antibody that is ChIP-validated whenever possible [17].

Q4: What are the key quality metrics for a successful ChIP-seq dataset? The ENCODE consortium recommends [4]:

- Sequencing Depth: At least 20 million uniquely mapped reads for point-source factors (e.g., transcription factors) in humans.

- FRiP Score: >1%. This measures the signal-to-noise ratio.

- Replicates: Minimum of two biological replicates, with high overlap between peak calls.

- Library Complexity: A high proportion of unique reads, indicating low levels of PCR duplication.

Research Reagent Solutions

Selecting the right reagents is critical for mitigating the technical challenges outlined above.

| Reagent / Solution | Function & Importance | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-Validated Antibodies | Specifically immunoprecipitate the target protein or modification in a cross-linked context. | Verify validation data (e.g., knockdown, peptide ELISA). Polyclonal or oligoclonal antibodies often perform better than monoclonals due to recognition of multiple epitopes [17]. |

| Dual Cross-linkers (DSG + Formaldehyde) | Stabilize protein-protein interactions prior to protein-DNA cross-linking. | Essential for mapping indirect chromatin binders (e.g., co-activators). DSG is used first (2 mM, 45 min), followed by standard formaldehyde cross-linking [19] [20]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatically fragments chromatin, an alternative to sonication. | Highly reproducible and consistent across samples. Preferable for native ChIP; can be used in X-ChIP for more uniform fragment sizes [22] [17]. |

| Magnetic Protein A/G Beads | Capture the antibody-target complex for immunoprecipitation. | High-quality beads reduce non-specific binding and background. Ensure the bead type is compatible with your antibody's host species and isotype [18] [16]. |

| Low-Input Library Prep Kits | Amplify limited ChIP DNA for sequencing while minimizing bias. | Kits like Accel-NGS 2S and ThruPLEX have been shown to retain high complexity and sensitivity with sub-nanogram inputs [15]. |

Workflow and Relationship Diagrams

Technical Culprits and Their Impacts on ChIP-seq Complexity

This diagram visualizes the cause-and-effect relationship where errors in three key wet-lab steps lead to low-quality data and failed biological interpretation.

Optimal ChIP-seq Workflow for High-Complexity Data

This workflow chart outlines the critical decision points and optimized procedures at each step to prevent the issues highlighted above and ensure a successful outcome.

How does antibody specificity lead to false discoveries in peak calling?

Antibody specificity is the paramount factor influencing the success of a ChIP-seq experiment. When an antibody cross-reacts with multiple proteins, the resulting data represents a superposition of binding events from different proteins, making accurate analysis impossible and leading to false conclusions [23].

The resulting peaks will not accurately represent the binding sites of your protein of interest, compromising all subsequent biological interpretation. To minimize this risk:

- Utilize Validated Antibodies: Use antibodies that have been experimentally validated for ChIP-seq application [24].

- Employ Knockout Controls: The most accurate control is performing ChIP in a biological system where the native protein is absent (knockout or knockdown). This directly profiles the antibody's non-specific binding [23].

- Consider Tagged Proteins: If a high-quality antibody is unavailable, engineer your protein of interest with a ChIP-able tag. The proper control for this is to perform ChIP in a cell line with and without the engineered protein [23].

What is the impact of sequencing depth on peak calling accuracy and false discoveries?

Variation in sequencing depth is a major systematic technical bias that directly impacts peak detection sensitivity and comparability between samples [23]. Inadequate depth reduces the power to detect true enriched regions, while uneven depth complicates comparisons across samples or conditions.

Table 1: Sequencing Depth Guidelines and Normalization Methods

| Consideration | Impact on Analysis | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Overall Depth | Influences ability to detect enriched regions [23]. | Sequence sufficiently deep; requirements vary by target (e.g., punctate TFs vs. broad histone marks) [25]. |

| Input Control Depth | Input controls for technical biases; shallow input leads to undersampled background [23]. | Sequence input samples deeper than ChIP samples for robust background modeling [23]. |

| Normalization Method | Corrects for depth differences before comparative analysis [23]. | Choose based on experiment:• Scale Normalization: For same protein, different conditions.• Robust/Background Normalization: For global, unchanging binding.• External/Spike-in: For global changes in binding profiles [23]. |

How does the choice of peak calling algorithm influence downstream interpretation?

Peak calling is the critical first step in ChIP-seq data analysis, separating true biological signal from noise. The algorithm choice significantly affects the sensitivity, precision, and ultimate biological conclusions drawn from your data [26].

Table 2: Peak Caller Feature Comparison and Performance

| Method | Key Features | Recommended Application |

|---|---|---|

| MACS2 | Uses dynamic window sizes; employs a Poisson test for significance [26]. | Transcription Factor (TF) binding data; one of the best operating characteristics on simulated TF data [26]. |

| BCP | Uses multiple window sizes and local signal variability; employs a Poisson test [26]. | Excellent for both TF and histone mark data [26]. |

| GEM | Incorporates genome sequence information to identify binding events [26]. | TF data where precise motif localization is critical; achieves high fraction of peaks near a binding motif [26]. |

| MUSIC | Uses multiple window sizes to capture enriched regions of different widths [26]. | Histone mark data with broad domains [26]. |

| ZINBA | Explicitly combines ChIP and input signals; uses a posterior probability for ranking [26]. | -- |

| TM (Threshold-based) | Uses a normalized difference score; combines ChIP and input signals [26]. | -- |

Algorithms that use multiple window sizes (like BCP and MUSIC) are generally more powerful for detecting regions of varying widths. Methods that use a Poisson test (like MACS2 and BCP) to rank peaks have been shown to be more powerful than those using a Binomial test [26].

What role do controls and replicates play in reducing false positives?

Without proper controls and replicates, it is statistically impossible to distinguish true biological signal from technical artifacts and inherent biological variability [23].

Table 3: Essential Controls and Replicates for Robust ChIP-seq

| Control Type | What It Controls For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Input DNA | Differential susceptibility of genomic regions to sonication, cross-linking, and immunoprecipitation [23]. | Most common control. Essential for accounting for chromatin accessibility and technical biases [23]. |

| IgG Control | Background, non-specific antibody binding [23]. | Should ideally be from the same serum batch as the specific antibody. Often yields low DNA, requiring extra PCR cycles [23]. |

| Knockout (KO) Control | Non-specific binding of the antibody to other proteins or DNA [23]. | The most accurate control. Technically challenging; ensure cell viability after knockout [23]. |

| Biological Replicates | inherent biological variability and technical noise [23]. | Indispensable. Independently executed experiments are required to statistically distinguish biological changes from random noise [23]. |

How can PCR amplification artifacts be minimized to improve analysis fidelity?

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) is used to amplify DNA prior to sequencing but is a stochastic process and a significant source of variability and bias [23]. Over-amplification can lead to duplicates that inflate perceived enrichment in certain regions.

- Monitor Sequence Properties: Perform quality control to check if all samples have similar sequence properties (e.g., dinucleotide enrichment like CpG). Account for these differences during analysis if found [23].

- Avoid Over-Amplification: Use the minimal number of PCR cycles necessary to obtain sufficient library material [25].

- Account for GC Bias: Be aware that PCR can introduce GC-content bias, which requires specialized tools to correct during data processing [23].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for ChIP-seq Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| ChIP-grade Antibody | Immunoprecipitation of the specific DNA-protein complex. | Critical for success. Use validated antibodies. Recombinant monoclonals offer high specificity and reproducibility [24]. |

| Formaldehyde | Reversible cross-linking of proteins to DNA. | Essential for studying transcription factors (X-ChIP). Cross-linking time must be optimized (e.g., 2-30 min) and quenched with glycine [25] [24]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Enzymatic fragmentation of chromatin for nucleosome-level mapping. | Preferred for N-ChIP (native, no crosslinking). Digestion has sequence bias; requires time-course optimization for consistency [25] [24]. |

| Magnetic Protein A/G Beads | Capture of antibody-bound complexes. | Efficiently isolate immunoprecipitated complexes. Avoid high-speed centrifugation to prevent bead damage [24]. |

| Stringent Wash Buffers | Remove non-specifically bound material. | Higher salt/detergent (e.g., RIPA) gives cleaner results. Must be optimized for each new ChIP target [24]. |

| Spike-in Chromatin | External reference for normalization. | Added in known amounts from another species (e.g., Drosophila) to control for global changes and normalize between samples [23]. |

Experimental Workflow: From Sample to Analysis

The diagram below illustrates the key steps in a ChIP-seq workflow and highlights critical points where experimental quality directly impacts downstream analysis and the potential for false discoveries.

ChIP-seq Workflow and Critical Factors [25] [24] [23]. This workflow outlines the core steps of a ChIP-seq experiment, highlighting key points (in red) where experimental quality directly impacts downstream analysis and potential for false discoveries. Additional technical challenges at each step are shown in yellow.

Beyond Traditional ChIP-seq: Adopting Modern Enzymatic Methods for Inherently Cleaner Data

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the cornerstone of epigenomic profiling for decades, enabling researchers to map protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications genome-wide. However, traditional ChIP-seq suffers from several significant limitations, including high background noise, extensive cellular input requirements (millions of cells), and lengthy, complex protocols that involve cross-linking, chromatin fragmentation, and immunoprecipitation [27]. These challenges are particularly problematic for studying rare cell types or clinical samples with limited material.

The paradigm shift toward more efficient chromatin profiling technologies has yielded two powerful methods: CUT&RUN (Cleavage Under Targets and Release Using Nuclease) and CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation). These approaches address fundamental limitations of ChIP-seq by performing targeted chromatin profiling in situ, eliminating the need for cross-linking and solubilization, thereby achieving higher resolution with significantly lower background [28]. This technical advancement directly addresses the challenge of low sequencing complexity that has plagued ChIP-seq research.

Technology Comparison: CUT&RUN vs. CUT&Tag vs. ChIP-seq

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Chromatin Profiling Technologies

| Feature | ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | CUT&Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cell Input Requirements | 1-10 million cells [29] | 500,000 cells recommended; works down to 5,000 cells [27] [30] | 100,000 cells standard; works down to 1,000-5,000 cells for histone modifications [27] [31] |

| Protocol Duration | ~1 week (cells to sequencer) [27] | ~3 days [27] | ~1-2 days [32] [28] |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-40 million reads per library [27] | 3-8 million reads [27] [30] | 3-8 million reads [30] |

| Background Noise | High [27] [28] | Very low [27] [28] | Very low [32] [28] |

| Key Steps | Cross-linking, fragmentation, IP [27] | Antibody-guided MNase cleavage [28] | Antibody-guided Tn5 tagmentation [32] |

| Library Preparation | DNA purification, end repair, adapter ligation [28] | DNA end polishing, adapter ligation [28] | Direct tagmentation with pre-loaded adapters [32] [28] |

| Best Applications | Historical comparisons; when heavy cross-linking is essential [27] | Transcription factors, chromatin-associated proteins, broad histone marks [27] [28] | Histone modifications, high-throughput applications [27] [28] |

Workflow Diagrams

Diagram 1: Comparative Workflows of Chromatin Profiling Technologies. CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag eliminate multiple steps required in ChIP-seq, reducing protocol time and complexity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag Experiments

| Reagent | Function | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Antibodies | Target specific histone modifications or chromatin-associated proteins | Quality and specificity are critical; "ChIP-grade" doesn't guarantee success in CUT&RUN/CUT&Tag [27] [30] |

| pA/G-Tn5 Transposase (CUT&Tag) | Protein A/G fused to Tn5 transposase pre-loaded with sequencing adapters | Preferentially tagments antibody-targeted chromatin regions [32] |

| pA-MNase (CUT&RUN) | Protein A fused to micrococcal nuclease | Cleaves DNA at antibody-targeted sites [28] |

| Concanavalin A Beads | Immobilize permeabilized cells/nuclei | Bead clumping may occur but doesn't typically affect final results [31] |

| Digitonin | Permeabilize cell and nuclear membranes | Critical for antibody and enzyme access to chromatin; concentration may need optimization [33] |

| Formaldehyde | Cross-link proteins to DNA (optional) | Light cross-linking (0.1-1%, 1 min) can stabilize labile interactions; heavy fixation not recommended [30] |

| MgCl₂ | Activate MNase or Tn5 enzyme | Concentration and incubation time critical to prevent over-digestion [28] |

Technology Selection Guide

Diagram 2: Technology Selection Guide. This decision tree helps researchers select the appropriate chromatin profiling method based on their experimental conditions and expertise.

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Experimental Challenges and Solutions

Low DNA Yield After Tagmentation

Potential Causes:

Solutions:

High Background/Non-specific Tagmentation

Potential Causes:

Solutions:

Bead Clumping Issues

Potential Causes:

Solutions:

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the minimum number of cells required for CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag?

CUT&RUN can generate high-quality data with as few as 5,000 cells for most targets, though 500,000 cells are recommended for initial experiments [27] [30]. CUT&Tag can work with just 1,000-5,000 cells for histone modifications and approximately 20,000 cells for transcription factors and cofactors [31].

How do I choose between native and cross-linked conditions?

For most targets, native conditions (no cross-linking) are preferred [30]. However, light cross-linking (0.1% formaldehyde for 1-2 minutes) can be beneficial for:

- Labile histone modifications (e.g., acetylation marks) [30]

- Readers of labile PTMs (e.g., bromodomain proteins) [30]

- Transiently interacting proteins (e.g., chromatin remodelers) [30]

Heavy cross-linking (1% formaldehyde for 10 minutes), standard for ChIP-seq, is not recommended for CUT&RUN or CUT&Tag [30].

Can I use my ChIP-seq validated antibodies for CUT&RUN or CUT&Tag?

Not necessarily. "ChIP-grade" antibodies are not guaranteed to work in CUT&RUN or CUT&Tag assays [27] [30]. EpiCypher found that over 70% of antibodies to histone modifications display unacceptable cross-reactivity, even for well-studied marks like H3K4me3 and H3K27me3 [27]. Always test multiple antibodies when possible.

Which method is better for transcription factor profiling?

CUT&RUN is generally preferred for transcription factors and chromatin-associated proteins [27] [28]. The high salt concentration used in CUT&Tag can compete with weak TF-DNA binding, resulting in weaker signals [28]. CUT&RUN has been successfully used for diverse targets including transcription factors, chromatin readers, writers, and remodeling enzymes [27].

How should I process tissue samples for CUT&Tag?

For tissue samples, 1 mg of fresh tissue is sufficient for robust enrichment of histone marks [33] [31]. The tissue should be finely minced and processed into a single-cell suspension [33]. Note that CUT&Tag works well for histone modifications in tissues but does not efficiently enrich transcription factors—for these targets, CUT&RUN is recommended [33] [31].

What controls should I include in my experiments?

Always include a negative control using nonspecific IgG to monitor background and nonspecific signal [27]. For peak calling, standard ChIP-seq programs like MACS2 and SICER work well with CUT&RUN data [27]. SEACR is a peak caller specifically designed for CUT&RUN data [27].

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

The evolution of CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag technologies continues with the development of single-cell indexed CUT&Tag (sciCUT&Tag), which enables chromatin profiling at single-cell resolution using combinatorial barcoding strategies [34]. This approach dramatically increases throughput while reducing costs to approximately $0.11 per cell in library preparation and sequencing, compared to ~$0.85 per cell for standard droplet-based methods [34].

These technologies are also being adapted for simultaneous profiling of multiple chromatin epitopes in single cells and integrated with transcriptomic and proteomic analyses, providing unprecedented insights into gene regulatory mechanisms in heterogeneous cell populations [34] [32].

CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag represent a significant paradigm shift in chromatin profiling, effectively addressing the limitations of traditional ChIP-seq, particularly the challenge of low sequencing complexity. By enabling high-resolution mapping with minimal cellular input, reduced background, and streamlined protocols, these technologies have opened new possibilities for studying epigenetic regulation in rare cell populations and clinical samples. As these methods continue to evolve and become more accessible, they promise to dramatically accelerate our understanding of gene regulatory mechanisms in health and disease.

A high signal-to-noise ratio is crucial in epigenomics for accurately identifying true biological signals, such as protein-DNA interactions, against background noise. For years, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) has been the standard method, but it is notoriously hampered by high background noise. The advent of Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation (CUT&Tag) presents a revolutionary alternative, achieving a superior signal-to-noise ratio through a fundamentally different in-situ methodology. This technical guide explores the mechanistic basis for this improvement and provides troubleshooting support for researchers aiming to overcome the limitations of traditional ChIP-seq.

Technical Showdown: CUT&Tag vs. ChIP-seq

The superior performance of CUT&Tag stems from its core biochemical principle, which avoids the major pitfalls of the ChIP-seq workflow. The table below summarizes the key technical differences that contribute to CUT&Tag's low background.

| Comparison Factor | CUT&Tag | ChIP-seq |

|---|---|---|

| Assay Principle | In-situ targeted tagmentation [35] | In-vitro fragmentation & immunoprecipitation [35] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | High (Minimal background) [35] [27] | Lower (High background from non-specific binding & fragmentation) [35] [27] |

| Typical Cell Input | 100 - 100,000 cells [35] [36] | 100,000 - millions of cells [35] [27] |

| Protocol Duration | ~1-2 days [35] [36] | 2-5 days [35] |

| Key Background Sources | Minimal; primarily Tn5's slight preference for open chromatin [37] | Non-specific cross-linking, sonication fragmentation artifacts, and inefficient IP [27] [35] |

| Typical Sequencing Reads/Sample | 2 - 8 million [27] [36] | 20 - 40 million [27] |

The Core Mechanistic Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the critical procedural differences between the two methods, highlighting where background noise is introduced in ChIP-seq and how CUT&Tag minimizes it.

Diagram 1: The ChIP-seq workflow and its major sources of background noise.

Diagram 2: The CUT&Tag workflow and its key steps ensuring low background.

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My CUT&Tag library yield is very low, or the Bioanalyzer signal is weak. Should I proceed with sequencing? Yes, you can often still proceed successfully. CUT&Tag baselines are inherently lower than ChIP-seq. It is recommended to concentrate the library using a Speedvac and sequence it. Deeper sequencing can help capture the library diversity, and it is possible to obtain high-quality genomic data even with a low Bioanalyzer signal [36] [37].

Q2: I see signal in my IgG negative control, particularly in open chromatin regions. What is the cause? This background is often due to the slight preference of the Tn5 transposase for accessible chromatin. To minimize this, always use freshly harvested native nuclei (avoid lysis), include the high-salt wash step meticulously, and consistently run an IgG control for proper comparison and background assessment [37].

Q3: I am getting high read duplication rates in my sequencing data. How can I troubleshoot this? High duplication is common with low-concentration libraries. First, confirm you are using the recommended 100,000 native nuclei and a CUT&Tag-validated antibody. Then, optimize the number of PCR cycles (testing 14-18 cycles) to achieve a final library concentration >2 ng/µL. For some low-abundance targets, high duplication is a necessary trade-off, and duplicates can be bioinformatically removed using tools like Picard [37].

Q4: Can I use my existing ChIP-validated antibody for CUT&Tag? Antibody performance is not always transferable between methods. ChIP-grade antibodies can be unreliable in CUT&Tag due to the different conditions (e.g., high salt). It is strongly recommended to use an antibody that has been specifically validated for CUT&Tag, either by your own testing or a commercial vendor [27] [36].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful CUT&Tag experiments depend on high-quality, specific reagents. The following table lists the essential components.

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function | Considerations & Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Validated Primary Antibody | Binds specifically to the target (histone mark, transcription factor). | The most critical factor. Use CUT&Tag-validated antibodies whenever possible [27]. |

| pA/G-Tn5 Transposase | The engineered enzyme that binds the antibody and performs targeted tagmentation. | Pre-loaded with sequencing adapters for streamlined library prep [36]. |

| Concanavalin A Magnetic Beads | Provides a solid support to bind permeabilized cells/nuclei for all liquid handling steps. | Prevents loss of material during washes and incubations [36]. |

| Digitonin | A detergent used to permeabilize the cellular and nuclear membranes. | Allows antibodies and pA/G-Tn5 to access the chromatin interior [36]. |

| High-Salt Wash Buffer | Used after pA/G-Tn5 binding to remove loosely bound or nonspecific transposase. | A crucial step for reducing background in open chromatin [37] [36]. |

CUT&Tag achieves its higher signal-to-noise ratio through a paradigm shift from physical enrichment to in-situ enzymatic tagging. By eliminating cross-linking, random chromatin fragmentation, and the inefficient immunoprecipitation steps that plague ChIP-seq, CUT&Tag minimizes the primary sources of background noise. This results in a cleaner, more efficient assay that requires fewer cells, less sequencing, and provides higher-resolution data. For researchers grappling with the high background and low sequencing complexity of ChIP-seq, adopting CUT&Tag offers a robust path to more reliable and interpretable epigenomic profiles.

Core Advantages of CUT&Tag in Modern Epigenomics

CUT&Tag (Cleavage Under Targets and Tagmentation) represents a significant methodological shift from Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq), offering solutions to key limitations that have constrained epigenomic research, particularly those related to low sequencing complexity and input requirements.

Dramatically Reduced Cell Input: While traditional ChIP-seq typically requires 1-10 million cells per immunoprecipitation, CUT&Tag reliably generates high-quality data with only 100,000 cells and can be optimized down to much lower numbers for precious samples [27]. This addresses a fundamental bottleneck in studying rare cell populations.

Superior Data Quality with Lower Sequencing Depth: CUT&Tag provides increased specificity and signal-to-noise ratios, requiring only 3-8 million sequencing reads for high-quality profiles compared to 20-40 million reads for ChIP-seq [38] [27]. This efficiency directly counters sequencing complexity challenges.

Overcoming Heterochromatin Bias: Unlike ChIP-seq, which is biased against condensed, heterochromatic regions due to loss of these regions during solubilization, CUT&Tag robustly profiles marks like H3K9me3 over repetitive elements and retrotransposons [39]. This provides a more complete picture of the epigenomic landscape.

Experimental Workflow: From Cells to Sequencing Libraries

The following diagram illustrates the core CUT&Tag procedure, highlighting its streamlined nature compared to traditional methods.

Key Protocol Steps and Considerations:

Cell Preparation: Use 100,000 live cells per reaction whenever possible. For fragile cells or tissues, light fixation (0.1% formaldehyde for 2 minutes) is acceptable, but over-fixation leads to weaker signals [40].

Permeabilization and Binding: Adequate digitonin concentration is critical for permeabilizing cell membranes. Test cell sensitivity to digitonin to ensure proper antibody and enzyme entry [40].

Antibody Validation: Use validated antibodies specifically tested for CUT&Tag when available. Performance in ChIP-seq does not always translate to CUT&Tag due to methodological differences [27].

Tagmentation Optimization: The Mg2+ activation step must be carefully timed. Over-tagmentation can lead to high background, while under-tagmentation reduces library complexity [27].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for CUT&Tag Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Preparation | Concanavalin A-coated beads, Formaldehyde (Methanol-Free) #12606, Glycine Solution (10X) #7005 | Cell immobilization and light fixation; glycine stops fixation |

| Buffers | 10X Wash Buffer #31415, Digitonin Solution #163, Complete Wash Buffer (with Protease Inhibitor & Spermidine) | Maintain proper ionic conditions and permeabilization; prevent proteolysis and chromatin aggregation |

| Antibodies | H3K4me3 #9751 (positive control), IgG #2729 or #68860 (negative control), Target-specific antibodies | Target recognition; critical for specificity |

| Enzymatic Components | pA-Tn5 Transposase, Protein A-Tn5 fusion protein | Targeted DNA cleavage and adapter integration |

| Library Preparation | Nuclease-free water #12931, PCR reagents, Indexing primers | Library amplification and multiplexing |

Comparative Method Analysis

Table: Quantitative Comparison of Chromatin Profiling Methods

| Parameter | ChIP-seq | CUT&RUN | CUT&Tag |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Cell Input | 1-10 million [27] [41] | 500,000 (down to 5,000) [27] | 100,000 (can be optimized lower) [40] [27] |

| Sequencing Depth Required | 20-40 million reads [27] | 3-8 million reads [27] | 3-8 million reads [27] |

| Protocol Duration | ~7 days [27] | ~3 days [27] | ~3 days (slightly faster than CUT&RUN) [27] |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Lower (high background) [27] | Higher [27] | Higher [38] [27] |

| Heterochromatin Performance | Biased against condensed regions [39] | Improved coverage [39] | Best for repetitive elements/retrotransposons [39] |

| Technical Difficulty | Moderate (multiple challenging steps) [27] | Lower (easier to troubleshoot) [27] | Higher (sensitive to technique) [27] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

FAQ: We're observing low library yields after indexing PCR. What could be causing this?

Low yields can result from several factors related to the sensitive nature of CUT&Tag:

- Excessive nuclei: Too many nuclei can impede proper reagent access and reaction efficiency [27]

- Inadequate permeabilization: Insufficient digitonin prevents antibody and Tn5 entry [40]

- Tn5 enzyme issues: Improper storage or handling of the pA-Tn5 fusion protein [27]

- Over-fixation: Even light fixation beyond the recommended 0.1% for 2 minutes can reduce efficiency [40]

FAQ: Our CUT&Tag data shows high background noise. How can we improve specificity?

- Antibody validation: Ensure your antibody is specific for the target epitope; cross-reactivity is a common issue [27]

- Optimize antibody concentration: Titrate antibodies (test 1:50, 1:100, 1:200 dilutions) to find the optimal concentration [38]

- Control for tagmentation time: Excessive Mg2+ exposure leads to non-specific tagmentation [27]

- Include proper controls: Always run IgG control reactions to establish background levels [27]

FAQ: How does CUT&Tag performance compare to established ChIP-seq datasets?

Recent benchmarking shows CUT&Tag recovers approximately 54% of known ENCODE ChIP-seq peaks for histone modifications like H3K27ac and H3K27me3 [38]. The peaks detected by CUT&Tag typically represent the strongest ENCODE peaks and show the same functional and biological enrichments [38]. This makes CUT&Tag highly suitable for comparative analyses while offering substantial resource savings.

FAQ: Can CUT&Tag be applied to transcription factors and low-abundance targets?

While CUT&Tag excels for histone modifications, profiling transcription factors and low-abundance targets requires additional optimization [27]. CUT&RUN may be more reliable for these applications, especially for researchers new to in situ mapping techniques [27]. For challenging targets, consider:

- Increasing cell input (up to 200,000-500,000 cells)

- Testing multiple antibody sources and concentrations

- Extending incubation times with primary antibody

- Using crosslinking conditions (though lighter than ChIP-seq)

Sample-Specific Protocol Adaptations

For Fixed Cells:

- Use fresh formaldehyde (0.1% final concentration) for 2 minutes at room temperature [40]

- Quench with 100 μl of 10X Glycine Solution per 1 ml of fixed cell suspension [40]

- Fixed cell pellets can be stored at -80°C for up to 6 months [40]

For Tissue Samples:

- Finely mince 1 mg of fresh tissue using a scalpel on ice [40]

- Disaggregate into single-cell suspension with 20-25 strokes in a Dounce homogenizer [40]

- Process through fixation and washing steps as with cells [40]

The relationship between sample preparation, experimental parameters, and outcomes can be visualized as follows:

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

CUT&Tag's compatibility with low-input requirements makes it particularly valuable for:

- Rare cell populations: Stem cells, circulating tumor cells, and subpopulations from clinical samples [41]

- Single-cell epigenomics: The method is amenable to scaling down for single-cell applications [38]

- Mapping challenging genomic regions: Particularly effective for heterochromatic regions and repetitive elements that are problematic for ChIP-seq [39]

When implementing CUT&Tag, begin with well-characterized histone marks like H3K4me3 or H3K27ac before progressing to more challenging targets like transcription factors. Always include appropriate positive and negative controls, and leverage existing benchmarking data to inform experimental design and analysis parameters [38] [27].

Leveraging Low-Input Advantages to Further Minimize Complexity and Cost

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation followed by sequencing (ChIP-seq) is the established method for mapping genome-wide protein-DNA interactions and histone modifications. However, standard protocols require substantial cell numbers—often millions—creating a significant barrier for studying rare cell populations. Recent methodological breakthroughs have successfully minimized input requirements to just thousands of cells while simultaneously addressing challenges related to protocol complexity, time, and cost. These advanced methods, including ChIPmentation and Ultra-Low-Input Native ChIP (ULI-NChIP), achieve this by strategically re-engineering key steps in the library preparation and chromatin handling workflows. By integrating tagmentation and optimizing reaction conditions, these approaches reduce material losses and maintain library complexity, making high-quality epigenetic profiling feasible even with severely limited starting material.

Key Low-Input ChIP-seq Protocols: A Comparative Analysis

Quantitative Comparison of Method Performance

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of three prominent low-input ChIP-seq methods, highlighting their performance metrics and optimal use cases.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Low-Input ChIP-seq Protocols

| Method Name | Key Innovation | Minimum Cell Number (Example Marks) | Typical Library Complexity | Protocol Duration | Best Suited For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HT-ChIPmentation [8] | Tn5 tagmentation on bead-bound chromatin; eliminates DNA purification. | 2,500–10,000 cells (H3K27Ac, CTCF) | >75% unique reads (down to 2.5k cells) | Single day | High-throughput studies; rapid profiling; FACS-sorted cells. |

| ULI-NChIP [42] | MNase-based native ChIP without cross-linking; optimized for minimal sample loss. | 1,000–10,000 cells (H3K27me3, H3K9me3) | High-complexity profiles from 1,000 cells | Multiple days | Histone modifications in rare in vivo cell populations (e.g., primordial germ cells). |

| ChIPmentation [43] | Combines standard ChIP with tagmentation of bead-bound chromatin. | 10,000–100,000 cells (H3K4me3, H3K27me3, CTCF) | High-quality, concordant with standard ChIP-seq | ~2 days | General-purpose low-input profiling for histone marks and transcription factors. |

Visualizing the High-Throughput ChIPmentation Workflow

HT-ChIPmentation stands out for its speed and minimal hands-on time. The following diagram illustrates its streamlined workflow, which is freely scalable from low- to high-throughput formats.

Figure 1: HT-ChIPmentation Workflow. This streamlined protocol eliminates DNA purification prior to library amplification, drastically reducing time and material loss.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Success

Successful low-input ChIP-seq relies on a carefully selected set of high-quality reagents and tools. The following table details the essential components for these sensitive assays.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Low-Input ChIP-seq

| Reagent / Tool | Critical Function | Low-Input Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Tn5 Transposase [8] [43] | Simultaneously fragments DNA and ligates sequencing adapters ("tagmentation"). | Enables library construction directly on bead-bound chromatin, minimizing sample loss. |

| Magnetic Beads (Protein G) [9] [8] | Solid-phase support for antibody-based chromatin capture. | Less porous than agarose, reducing background; ideal for small volumes and wash steps. |

| Validated Antibodies [4] [9] | Specific immunoprecipitation of target protein or histone mark. | Quality is paramount; use ChIP-validated antibodies. Efficiency varies greatly between lots. |

| Cell Sorting (FACS) [8] [42] | Isolation of rare or fixed cell populations. | Cells can be sorted directly into lysis buffer, enabling profiling of defined populations. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) [44] [42] | Enzymatic digestion of chromatin for NChIP protocols. | Yields precise nucleosomal fragmentation, often preferred for native ChIP on histone marks. |

Troubleshooting Guide & FAQs

Addressing Common Low-Input Experimental Challenges

Q1: My library complexity is low, with a high duplicate read rate. What steps can I take to improve this?

- Cause: The primary cause is an insufficient number of unique DNA molecules at the start of library amplification, often due to sample loss during clean-up steps or inefficient immunoprecipitation [8] [42].

- Solution:

- Eliminate DNA purification steps: Adopt protocols like HT-ChIPmentation that perform adapter extension and library amplification directly from bead-bound chromatin, thereby avoiding sample loss during DNA extraction and clean-up [8].

- Optimize IP efficiency: Ensure antibody quality and quantity are optimal. Pre-binding the antibody to magnetic beads before adding the chromatin sample can improve capture efficiency and reduce background [9].

- Verify sonication efficiency: Inefficient chromatin shearing can lead to low yields. Optimize sonication conditions by running a time-course and checking fragment size on an agarose gel [44].

Q2: I am observing high background signal in my low-input experiment. How can I increase the signal-to-noise ratio?

- Cause: Non-specific antibody binding, over-tagmentation, or insufficiently stringent wash conditions can contribute to high background [45] [46].

- Solution:

- Pre-clear the lysate: Incubate the chromatin lysate with protein A/G magnetic beads without antibody first to remove proteins that bind nonspecifically [45].

- Increase wash stringency: Ensure wash buffers are fresh and cold. Consider increasing the salt concentration slightly in later washes, but do not exceed 500 mM to preserve antibody-antigen interactions [45].

- Titrate the antibody: Too much antibody can increase background. Use the recommended amount (typically 1-10 μg) and test different concentrations for a new antibody [45] [46].

- Optimize tagmentation: For tagmentation-based methods, the reaction is highly robust over a range of transposase concentrations. However, excessive tagmentation can damage chromatin. The bead-bound nature of the chromatin in ChIPmentation offers inherent protection against over-tagmentation [43].

Q3: I am not getting any amplification product after the final PCR. What is wrong?

- Cause: This can result from extremely low immunoprecipitation efficiency, failed tagmentation/adapter ligation, or excessive cross-linking that masks epitopes and inhibits DNA recovery [44] [46].

- Solution:

- Include a positive control antibody: Always run a parallel IP with a reliable antibody (e.g., anti-H3K4me3) to confirm that the entire protocol is working correctly [9].

- Reduce cross-linking time: Over-cross-linking can make epitopes inaccessible. Reduce formaldehyde fixation time to the minimum required (e.g., 10 minutes) and ensure it is promptly quenched with glycine [44] [45].

- Check the reverse cross-linking step: Ensure complete reversal of cross-links by incubating at 95°C or with Proteinase K treatment [46].

- Verify reagent quality: Use fresh buffers and high-quality magnetic beads. Contaminated or degraded reagents are a common point of failure [45].

Q4: My chromatin is under-fragmented or over-fragmented. How can I optimize this?

- Cause: Fragmentation conditions (sonication power/duration or MNase concentration) are not calibrated for the specific low-input sample [44].

- Solution:

- For sonication: Perform a sonication time-course. Remove small aliquots at different time points, de-crosslink, and run on a gel to determine the optimal duration to achieve fragments between 200-1000 bp [44].

- For enzymatic fragmentation (MNase): Perform a digestion titration. Set up several reactions with different dilutions of MNase to find the concentration that produces a dominant ~150 bp mononucleosome band [44] [42].

Protocol-Specific Optimization FAQs

Q5: How do I generate a good input control for a low-input HT-ChIPmentation experiment?

- Solution: A robust and low-material input control can be prepared by taking a small aliquot (e.g., 500 cell equivalents) of your sonicated chromatin before immunoprecipitation. This chromatin can be processed through direct tagmentation and library amplification in parallel with your HT-ChIPmentation samples. This method requires minimal material and provides an adequate control for peak calling [8].

Q6: Can I use these low-input methods for transcription factors (TFs), or are they only for histone marks?

- Solution: Yes, but success is more challenging. Methods like ChIPmentation and HT-ChIPmentation have been successfully used for TFs like CTCF and GATA1 starting from 100,000 cells [8] [43]. However, the feasibility depends heavily on the abundance of the TF and the quality of the antibody. Histone marks are generally more abundant and thus easier to profile from ultra-low inputs [42].

Hands-On Troubleshooting: A Step-by-Step Protocol to Rescue and Optimize Your ChIP-seq Experiments

Why is Library Complexity Critical for ChIP-seq Success?

Library complexity refers to the diversity of unique DNA fragments in your sequencing library. High complexity is crucial as it ensures that the data generated is a true representation of protein-DNA interactions across the genome. Low-complexity libraries, dominated by PCR duplicates from over-amplification of limited starting material, lead to high background noise, reduced statistical power, and unreliable peak calling, ultimately compromising the biological validity of your entire study [47] [48].

Assessing complexity pre-sequencing allows you to catch these issues early, saving valuable time and sequencing resources. The following guide provides actionable steps and metrics to ensure your ChIP-seq data is of the highest quality from the start.

Key Metrics for Assessing Library Complexity

The table below summarizes the core metrics used to evaluate library quality and complexity. These are typically calculated from aligned BAM files using tools like ChIPQC [48].

| Metric | Description | Good Quality Indicator |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Redundant Fraction (NRF) | Fraction of unique, non-duplicated mapped reads [49]. | An ideal experiment should have an NRF indicating less than three reads per position [49]. |

| Reads in Peaks (RiP / FRiP) | Percentage of reads falling within called peak regions; a key "signal-to-noise" measure [48]. | Transcription Factors: ~5% or higher [48].Broad Markers (e.g., Pol II): ~30% or higher [48]. |

| Relative Strand Cross-Correlation (RSC) | Measures the signal-to-noise ratio based on the asymmetry of reads mapping to forward and reverse strands [5]. | RSC ≥ 1.0 indicates successful enrichment; RSC ≥ 1.5 indicates a highly clustered library [5]. |

| SSD (Standard Deviation of Signal) | Measures the uniformity of read coverage across the genome; higher scores indicate stronger enrichment [48]. | A "good" or enriched sample typically has a higher SSD due to significant read pile-up in specific regions [48]. |

| Reads in Blacklisted Regions (RiBL) | Percentage of reads in genomic regions with known artificially high signal (e.g., centromeres) [48]. | Lower percentages are better. A high RiBL can indicate background noise and may explain a high SSD [48]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function / Note |

|---|---|

| ChIP-Grade Antibody | Validated for immunoprecipitation following cross-linking; specificity is paramount [50]. |

| Protein A/G Magnetic Beads | For antibody binding and immunoprecipitation; choice of Protein A or G depends on antibody species and isotype [50]. |

| Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) | Used for enzymatic chromatin digestion to achieve fragments of 150–900 bp [51]. |

| Formaldehyde | For cross-linking proteins to DNA; concentration and fixation time (typically 1% for 10-20 min) must be optimized [50]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Added to lysis buffers to prevent protein degradation during sample preparation [50]. |

| Sonicator | For physical shearing of cross-linked chromatin; conditions must be optimized for each cell type [51]. |

| Tn5 Transposase | Used in modern protocols like ChIPmentation for simultaneous fragmentation and adapter tagging, improving efficiency with low inputs [8]. |

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Low Complexity

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommendations & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High Background & Low Signal | Excessive sonication, over-crosslinking, or insufficient starting material [51] [52]. | - Optimize sonication: Aim for fragments between 200–1000 bp. Perform a time course and check fragment size on a gel [51] [52].- Reduce cross-linking: Avoid fixation longer than 30 minutes. Quench efficiently with glycine [50].- Increase input: Use more chromatin per IP (e.g., 5–10 µg) and ensure accurate cell counts [51]. |

| Low Library Complexity & High Duplication | Over-amplification by PCR due to low immunoprecipitation efficiency or very low cell numbers [47]. | - Use sufficient cells: Start with an adequate number of cells. For very low cell numbers, use specialized protocols like HT-ChIPmentation [8].- Limit PCR cycles: Use the minimal number of PCR cycles needed for library amplification.- Pre-clear lysate: Incubate lysate with protein A/G beads before IP to remove nonspecific binders [52]. |

| Poor RiP/FRiP Score | Inefficient immunoprecipitation, poor antibody quality, or incorrect control use [48] [50]. | - Validate antibodies: Use ChIP-grade antibodies and verify specificity. A blocked antibody (with its peptide) can serve as a negative control [50].- Use correct controls: Input DNA or mock IP (IgG) controls are essential for accurate peak calling [5] [49]. Be aware that some IgG controls can show unexpected enrichment [5]. |

| High RiBL Score | Reads mapping to artifactual regions like centromeres and telomeres [48]. | - Consult blacklists: Use standardized genomic blacklist regions (e.g., from ENCODE) during data analysis to filter out these problematic areas [48]. |

Detailed Protocol: Chromatin Fragmentation & QC

Proper chromatin fragmentation is a critical first step that directly impacts library complexity. The workflow below outlines the two primary methods.

Key Steps for Success:

- Optimization is Non-Negotiable: The optimal sonication time or MNase concentration must be determined empirically for each cell type and fixation condition [51] [50].

- Avoid Over-Sonication: >80% of DNA fragments shorter than 500 bp can damage chromatin and lower IP efficiency [51].

- Verify with Gel Electrophoresis: Always run purified DNA on a 1% agarose gel to confirm the fragmentation smear is in the 150-900 bp range (1-6 nucleosomes) [51].

Advanced Methods: HT-ChIPmentation for Low-Input Samples

When working with low cell numbers (a few thousand cells), traditional protocols often lead to significant material loss and low complexity. HT-ChIPmentation is an advanced protocol that dramatically improves outcomes [8].

Core Innovation: HT-ChIPmentation combines chromatin immunoprecipitation with tagmentation (using Tn5 transposase to simultaneously fragment DNA and add sequencing adapters). Its key improvement is eliminating the DNA purification step before library amplification, drastically reducing material loss and processing time [8].

Impact on Complexity: As shown in the logic below, this protocol directly targets and mitigates the primary causes of low complexity in rare cell samples.

Benefits: This method is extremely rapid (can be completed in a single day), maintains high library complexity with >75% unique reads down to 2,500 cells, and is easily scalable for high-throughput studies [8].

Before proceeding to the sequencer, ensure you have addressed the following critical points from your experimental and bioinformatic QC:

- Experimental Wet-Lab QC: Have you verified your chromatin fragmentation profile on a gel? Is your IP efficient, and have you used the correct, validated antibody? [51] [50]

- Bioinformatic Pre-Sequencing QC: After alignment, have you calculated your FRiP/RiP, RSC, and NRF? Are the values within the expected ranges for your target? [5] [48]

- Control for Biases: Are you using a matched input or appropriate mock IP control to account for technical biases like open chromatin structure? [47]

- Protocol Suitability: For low-input samples, have you considered modern methods like HT-ChIPmentation to preserve complexity? [8]

By systematically integrating these pre-sequencing QC steps, you lay the foundation for robust, reliable, and biologically meaningful ChIP-seq data, directly addressing the core challenge of low sequencing complexity in modern epigenomics research.

Troubleshooting Guides

This section addresses common wet-lab challenges in ChIP-seq, providing targeted solutions to improve sequencing complexity and data quality.

Cross-Linking Troubleshooting

Problem: Inefficient or excessive cross-linking

Cross-linking is a critical step for preserving protein-DNA interactions. Imbalances can severely impact downstream results [53] [54].

| Problem & Symptoms | Root Cause | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Under-cross-linking:Poor yield, complex disassociation | Incubation time too short; formaldehyde concentration too low; using old formaldehyde [53] [54] | • Use fresh, high-quality formaldehyde (e.g., 1% final concentration) [54]• Optimize time: Test 10, 20, and 30 minutes at room temperature [54]• Do not cross-link for less than 5-10 minutes [54] |

| Over-cross-linking:Masked epitopes, poor shearing, high background, inhibited reverse cross-linking [53] [54] | Incubation time too long; formaldehyde concentration too high [53] | • Avoid cross-linking longer than 30 minutes [54]• Ensure proper quenching with 125 mM glycine for 5 minutes [55] [54] |

Chromatin Shearing and Fragmentation Troubleshooting

Proper fragmentation is essential for high resolution and low background. The optimal method (enzymatic or sonication) depends on your tissue and protein of interest [56].

Problem: Chromatin is under-fragmented (large DNA fragments)

- Symptoms: Increased background noise, lower resolution [56].

- Causes: Over-cross-linked cells; too much input material per reaction [56].

- Solutions:

- For both methods: Shorten cross-linking time (within 10-30 minute range) [56].

- Enzymatic (Micrococcal Nuclease): Increase the amount of MNase enzyme or perform a digestion time course [56].

- Sonication: Conduct a sonication time course; reduce the amount of cells or tissue per sonication volume [56].

Problem: Chromatin is over-fragmented

- Symptoms: DNA is mostly mono-nucleosomal; can disrupt chromatin integrity and denature antibody epitopes, leading to diminished signal [56].

- Causes: Too much enzyme or sonication power; too long of a digestion/sonication time [56].

- Solutions:

Problem: Foaming during sonication

- Cause: Sonicator tip is not positioned correctly [53].

- Solution: Use 1.7 ml tubes with no more than 400 µl of sample and keep the sonicator tip very close to the bottom of the tube [53].

Problem: Chromatin degradation

- Cause: Samples overheating during shearing [53].

- Solution: Keep samples on ice at all times and incubate on wet ice between sonication pulses [56] [53].

Immunoprecipitation and PCR Troubleshooting

Problem: High background in PCR (high amplification in no-antibody control)

- Causes:

- Solutions:

Problem: No amplification of product

- Causes:

- Solutions:

Optimizing Key Steps: Detailed Experimental Protocols

Optimizing Chromatin Fragmentation

Accurate fragmentation is fundamental. Below are detailed protocols for optimizing both enzymatic and sonication methods.

Enzymatic Fragmentation (Micrococcal Nuclease) Optimization Protocol

This protocol helps determine the correct amount of Micrococcal Nuclease (MNase) for your specific cell or tissue type [56].

- Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 125 mg of tissue or 2 x 10^7 cells (equivalent to 5 IPs). Stop after the nuclei preparation step [56].

- Set up digestion reactions: Transfer 100 µl of the nuclei preparation into each of 5 individual tubes on ice [56].

- Dilute enzyme: Dilute the stock MNase 1:10 in the provided buffer [56].

- Test enzyme volumes: Add different volumes of the diluted MNase to each tube. A standard test uses 0 µl, 2.5 µl, 5 µl, 7.5 µl, and 10 µl [56].

- Digest and stop: Incubate all tubes for 20 minutes at 37°C with frequent mixing. Stop the reaction by adding 0.5 M EDTA and placing tubes on ice [56].

- Purify and analyze DNA: Pellet nuclei, resuspend in lysis buffer, and sonicate briefly to lyse nuclei. Purify DNA from each sample and analyze fragment size on a 1% agarose gel [56].

- Determine optimal condition: Identify the volume of diluted MNase that produces a dominant smear of DNA between 150–900 bp. The optimal volume of stock MNase to use for one IP is this test volume divided by 10 [56].

Sonication-Based Fragmentation Optimization Protocol

This protocol determines the optimal number of cycles or duration of sonication [56].

- Prepare cross-linked nuclei from 100–150 mg of tissue or 1x10^7–2x10^7 cells per 1 ml of lysis buffer [56].

- Perform sonication time-course: Fragment the chromatin by sonication. Remove a 50 µl aliquot of chromatin after different intervals (e.g., after each 1-2 minutes of total sonication time) [56].

- Purify and analyze DNA: Clarify each aliquot by centrifugation. Purify the DNA and analyze the fragment size on a 1% agarose gel [56].

- Determine optimal condition: Choose the sonication time that generates the optimal DNA fragment size. For cells fixed for 10 minutes, ideal sonication produces a smear where ~90% of DNA fragments are less than 1 kb. Avoid over-sonication, indicated by >80% of fragments being shorter than 500 bp, as this damages chromatin and lowers IP efficiency [56].

Expected Chromatin Yields

Knowing the expected yield from your starting material helps diagnose issues early. The table below provides typical yields from 25 mg of various tissues or 4 million HeLa cells [56].

| Tissue / Cell Type | Total Chromatin Yield (Enzymatic Protocol) | Expected DNA Concentration (Enzymatic Protocol) |

|---|---|---|

| Spleen | 20–30 µg | 200–300 µg/ml |

| Liver | 10–15 µg | 100–150 µg/ml |

| Kidney | 8–10 µg | 80–100 µg/ml |