Solving Poor RNA-Seq Alignment Rates: A Researcher's Troubleshooting Guide from Basics to Best Practices

Poor alignment rates in RNA-Seq can compromise entire studies, leading to data loss and unreliable conclusions.

Solving Poor RNA-Seq Alignment Rates: A Researcher's Troubleshooting Guide from Basics to Best Practices

Abstract

Poor alignment rates in RNA-Seq can compromise entire studies, leading to data loss and unreliable conclusions. This guide provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework for diagnosing and resolving low mapping rates. We cover foundational principles, methodological choices, step-by-step troubleshooting, and validation strategies based on current, large-scale benchmarking studies. By systematically addressing issues from sample quality and reference genome selection to tool parameterization, this article equips scientists to optimize their RNA-Seq workflows for robust, reproducible results in both basic research and clinical applications.

Understanding RNA-Seq Alignment: Why Your Reads Don't Map and What Constitutes Success

What is alignment rate and why is it a critical QC metric?

Alignment rate refers to the percentage of sequencing reads that successfully map to a reference genome or transcriptome. This metric is a fundamental quality control (QC) checkpoint in RNA-seq analysis because a low rate can indicate issues with the sample, library preparation, or sequencing itself, potentially leading to incorrect biological conclusions [1]. While the exact threshold for an "acceptable" rate depends on the organism and experimental protocol, for high-quality data, mapping rates to a genomic reference are typically expected to be >80% [2] [3]. Rates below 70% are a strong indication of poor quality and warrant investigation [1].

What are the benchmark alignment rates for different RNA-seq protocols?

The choice of library preparation protocol significantly influences the composition of your RNA-seq library and, consequently, the expected alignment rate. The table below summarizes benchmarks for common approaches.

| Protocol / Sample Type | Expected Alignment Rate | Primary Reason for Unmapped Reads |

|---|---|---|

| Poly(A) Enrichment | High (>80-90%) [2] | Effectively removes ribosomal RNA (rRNA), enriching for mature mRNA. |

| Total RNA (with rRNA Depletion) | Variable | Efficiency of the rRNA depletion method; remaining rRNA reads often multi-map [4]. |

| Total RNA (no Depletion) | Low (e.g., 36-60%) [2] | Abundant rRNA constitutes ~80% of the library; these reads are often multi-mapped and discarded [4] [2]. |

Why does total RNA-seq typically yield a lower mapping rate?

A common challenge is low alignment rates from total RNA-seq data, even when using a complete reference genome. This is primarily due to ribosomal RNA (rRNA) [2] [5].

- Abundance and Multi-mapping: rRNA can make up 80% of the total RNA in a cell [4]. The genome contains multiple, nearly identical copies of rRNA genes. Reads originating from these regions will map to many genomic locations simultaneously. Most aligners, like STAR with default settings, will discard reads that map to more than 10 locations to ensure mapping quality, classifying them as unmapped [2].

- Missing Reference Sequences: In some cases, not all copies of rRNA genes are placed on reference genome chromosomes. If these sequences are absent from your reference, the corresponding reads will have nowhere to map [2].

How can I troubleshoot and improve a low alignment rate?

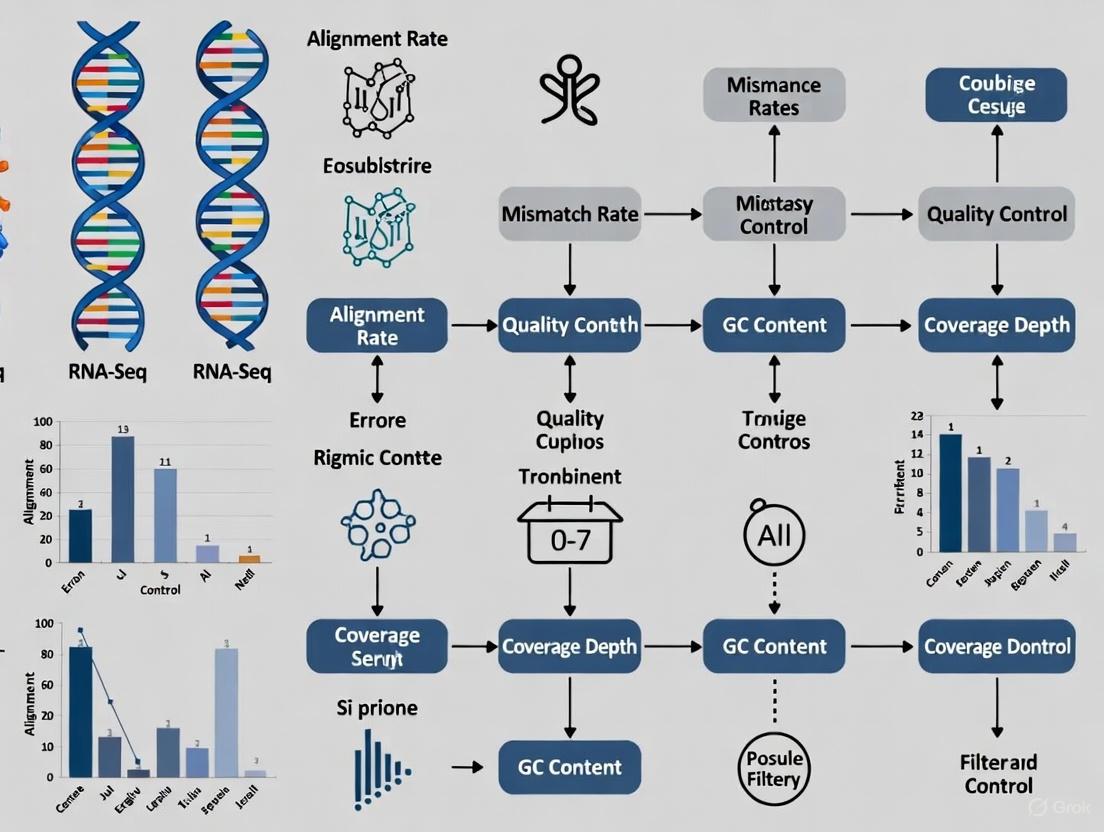

Systematically investigating the source of unmapped reads is key to resolving low alignment rates. The following workflow outlines a logical troubleshooting path.

The corresponding methodologies for the key troubleshooting steps are detailed below.

1. Preprocessing and Quality Control of Raw Data

- Methodology: Use tools like FastQC to visualize base quality scores, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences [1] [6]. Follow this with a trimming tool like fastp, Trimmomatic, or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the reads [7] [6]. Running FastQC again post-trimming confirms the improvement.

2. Screening for and Filtering Ribosomal RNA

- Methodology: If you suspect high rRNA content (common in total RNA-seq), align your FASTQ reads to a database of rRNA sequences using a rapid aligner like Bowtie2. Use the

--unparameter to output the unmapped reads, which will be your rRNA-filtered dataset. This filtered set can then be used for your primary alignment with an RNA-seq aware aligner like STAR or TopHat2 [5].

3. Verifying Reference Genome and Aligner Parameters

- Methodology: Ensure you are using the most comprehensive reference genome available, including all contigs and not just the primary chromosomes, as some rRNA genes may be on unplaced sequences [2]. Furthermore, some multi-mapping reads can be rescued by adjusting aligner parameters. For example, in STAR, you can increase the

--outFilterMultimapNmaxparameter, but do so cautiously as it may increase false alignments [2].

What are the essential reagents and tools for these procedures?

The following toolkit is essential for diagnosing and improving alignment rates.

| Tool or Reagent | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| FastQC | Provides initial quality control report on raw FASTQ files, highlighting adapter content and quality issues [1] [7]. |

| fastp / Trimmomatic / Cutadapt | Trims adapter sequences and low-quality bases from reads to improve mapping success [1] [6]. |

| Bowtie2 | A fast aligner used to screen reads against an rRNA database to filter them out before main alignment [5]. |

| STAR | A splice-aware aligner for RNA-seq data; its parameters (e.g., --outFilterMultimapNmax) can be tuned [2] [3]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNAs with known sequences that can be added to a sample to serve as a ground truth for evaluating alignment and error-correction performance [8]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Laboratory reagents (e.g., based on RNase H method) to remove rRNA from total RNA samples during library prep, reducing the burden of unmappable reads [4]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. Why is a high rRNA content in my sequencing data a problem and how can I fix it? Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) can constitute up to 80% of cellular RNA. When it is not effectively removed during library preparation, it consumes the majority of your sequencing reads, drastically reducing the number of reads available for your transcripts of interest and leading to poor alignment rates for non-ribosomal regions [4]. To address this:

- Verify Depletion Efficiency: Use tools like FastQC to check the percentage of reads aligning to rRNA sequences in your raw data [1].

- Choose the Right Depletion Method: Common methods include ribosomal RNA removal using magnetic beads with DNA probes or RNase H-mediated degradation. Bead-based methods may offer greater enrichment but can be more variable, whereas RNase H methods are often more reproducible [4].

- Be Aware of Trade-offs: Depletion is an additional step that can introduce variability, and some genes may be unintentionally depleted due to off-target effects. Ensure your research question does not require the study of rRNA itself [4].

2. My RNA is degraded (low RIN). Can I still proceed with RNA-Seq, and what adjustments are needed? Yes, but it requires specific library preparation protocols. RNA degradation, often indicated by a low RNA Integrity Number (RIN), is a major challenge, especially with clinical samples [9]. The degradation process is universal and random, leading to significant differences in transcriptome profiles even with slight degradation [9].

- Avoid Poly-A Selection: Do not use oligo(dT) enrichment methods, as they require an intact poly-A tail, which is often missing in degraded RNA [4].

- Use rRNA Depletion with Random Priming: Protocols that utilize ribosomal depletion and random hexamer primers for cDNA synthesis perform significantly better with degraded samples because they do not rely on the 3' end of transcripts [4].

- Consider 3' mRNA-Seq Methods: For heavily degraded samples (RIN as low as 2), 3' mRNA-seq technologies (e.g., DRUG-seq, BRB-seq) have been shown to provide robust and reproducible gene expression data, as they are designed to profile the 3' end of transcripts [10].

3. What are the signs of adapter contamination, and how do I remove it from my data? Adapter contamination occurs when sequencing adapters are not properly cleaned up after library preparation and are sequenced instead of your sample. This wastes sequencing cycles and can lower mapping rates.

- Identification: Analyze your raw FASTQ files with FastQC. A tell-tale sign is an over-representation of specific sequences (the adapter sequences) across your reads [1]. In post-alignment QC, you might also see a sharp peak around 70-90 bp in the fragment size distribution, indicating adapter dimers [11].

- Solution - Trimming: Use preprocessing tools like

fastp[6],Cutadapt[6], orTrimmomatic[1] to identify and trim adapter sequences from your reads. It is crucial to apply trimming cautiously to avoid losing true biological signal [1].

4. Beyond these three culprits, what other factors can lead to low alignment rates?

- Reference Genome Mismatch: Using an incorrect or poorly annotated reference genome is a common cause. Always use the reference that most closely matches your species and strain [1].

- Sample Cross-Contamination: The presence of DNA or RNA from an unintended organism (e.g., host contamination in pathogen studies) will result in many reads not mapping to your target reference [1].

- High PCR Duplication Rates: Excessive PCR amplification during library prep can create artificial duplicates, reducing library complexity and potentially skewing alignment metrics [1] [11].

- Technical Errors in Library Prep: Pipetting errors, use of degraded reagents, or miscalculations in adapter-to-insert ratios can all lead to library preparation failures and subsequently low yields and poor alignment [11].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving High Ribosomal RNA Alignment

A high percentage of reads aligning to rRNA genes indicates inefficient ribosomal RNA depletion during library construction. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and address this issue.

Table 1: Common rRNA Depletion Methods and Their Characteristics

| Method | Principle | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Probe-Based Magnetic Depletion | DNA probes complementary to rRNA are hybridized and removed with magnetic beads. | High depletion efficiency under optimal conditions [4]. | Can show greater variability between samples [4]. |

| RNase H-Mediated Depletion | DNA probes hybridize to rRNA, followed by RNase H digestion of the RNA-DNA hybrid. | More reproducible performance across samples [4]. | Depletion enrichment may be more modest compared to bead-based methods [4]. |

Guide 2: Managing Experiments with Degraded RNA Samples

Working with degraded RNA, common in clinical or archival samples, requires a shift in both wet-lab and computational strategies. The key is to accept the data limitations and choose a protocol robust to RNA fragmentation.

Table 2: RNA-Seq Protocol Suitability for Degraded Samples

| Library Preparation Protocol | Recommended for Degraded RNA? | Key Reason | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| Poly-A Enrichment | Not Recommended | Relies on an intact poly-A tail, which is lost in general RNA degradation [4]. | Standard for high-quality RNA. |

| rRNA Depletion + Random Priming | Recommended | Uses random hexamers to prime cDNA synthesis from any part of the transcript, not just the 3' end [4]. | Preferred method for moderately degraded samples. |

| 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., DRUG-seq) | Highly Recommended | Specifically designed to profile the 3' end of transcripts, which is more stable in many degradation scenarios [10]. | Robust for RIN values as low as 2 [10]. |

Experimental Protocol: RNA-Seq Library Preparation from Degraded RNA using rRNA Depletion and Random Priming

RNA Quality Assessment:

rRNA Depletion:

- Proceed directly to ribosomal RNA depletion. Do not perform poly-A selection.

- Use a commercial rRNA depletion kit (e.g., Ribo-Zero Plus) following the manufacturer's instructions. These kits typically use a pool of DNA probes to hybridize and remove rRNA [4].

Library Construction:

- Use the depleted RNA for library prep.

- The critical step is to use random hexamer primers (not oligo-dT) for the reverse transcription reaction to generate first-strand cDNA. This allows for the amplification of RNA fragments that lack a poly-A tail [4].

- Complete the remaining steps of the library preparation protocol as standard (second-strand synthesis, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification).

Guide 3: Identifying and Removing Adapter Contamination

Adapter contamination arises from incomplete purification of the final sequencing library, leaving short fragments where adapters have ligated to each other instead of a DNA insert.

Experimental Protocol: Adapter Trimming with fastp

fastp is a widely used tool for fast and all-in-one preprocessing of FASTQ files, including adapter trimming [6].

Install

fastp:- It can be installed via conda:

conda install -c bioconda fastpor from source.

- It can be installed via conda:

Basic Command for Adapter Trimming:

- For a paired-end sequencing run, a typical command is:

-i/-I: Input read files.-o/-O: Output files for cleaned reads.--adapter_fasta: Provide a FASTA file containing the adapter sequences used in your library prep kit. Many common adapter sequences are detected automatically byfastp.

Post-Trimming Quality Control:

- Always run FastQC or MultiQC on the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm that the overrepresented adapter sequences have been removed and that overall data quality (e.g., per-base sequence quality) has improved [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for Troubleshooting RNA-Seq Alignment

| Item | Function | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Selectively removes rRNA from total RNA samples, enriching for mRNA and other non-ribosomal RNAs. | Essential for samples where poly-A selection is not suitable (e.g., degraded RNA, non-polyadenylated RNA) [4]. |

| RNA Stabilization Reagents (e.g., PAXgene) | Preserves RNA integrity immediately upon sample collection by inhibiting RNases. | Critical for preserving high-quality RNA from blood samples or tissues with high RNase activity [4]. |

| Solid Phase Reversible Immobilization (SPRI) Beads | Magnetic beads used for size-selective cleanup of DNA/RNA libraries, removing adapter dimers and short fragments. | Used in the library purification step to remove excess adapters and primer dimers that cause adapter contamination [11]. |

| Spike-in RNA Controls (e.g., ERCC, SIRV) | Exogenous RNA molecules added to the sample in known quantities. Used for quality control and normalization. | Helps distinguish technical artifacts from biological changes; vital for assessing library prep efficiency in degraded samples [10]. |

| FastQC Software | A quality control tool that provides an overview of sequencing data, highlighting issues like adapter contamination, high rRNA content, and low-quality bases. | The first step in any RNA-Seq analysis pipeline to diagnose the root cause of poor alignment rates [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental difference in how these methods affect mappable reads? Poly(A) enrichment uses oligo(dT) beads to positively select for messenger RNA (mRNA) with poly(A) tails, resulting in a high percentage of reads mapping to exonic regions. In contrast, ribosomal depletion uses probes to remove ribosomal RNA (rRNA), allowing all other RNA types to remain. This includes non-coding RNAs and pre-mRNA, which leads to a lower proportion of exonic reads and more reads mapping to intronic and intergenic regions [12] [13] [14].

2. I am getting poor mappability with my ribosomal-depleted libraries. Is this expected? Yes, to an extent. Ribosomal depletion libraries inherently yield a lower fraction of reads that map to the exonic transcriptome. For example, one study found that while poly(A) selection yielded 70-71% usable exonic reads, rRNA depletion yielded only 22-46% [13]. This is not necessarily poor performance but a characteristic of the method, as it captures a broader range of RNA biotypes. Achieving exonic coverage comparable to poly(A) enrichment requires significantly greater sequencing depth—often 50% to 220% more reads [13].

3. Why does my poly(A)-selected data show a strong bias towards the 3' end of transcripts? This bias is introduced during the library preparation. The oligo(dT) primers used in poly(A) enrichment bind to the poly(A) tail at the 3' end of transcripts. This can lead to preferential sequencing of the 3' end, especially if the RNA is partially degraded or the reverse transcription conditions are not optimized [12] [13] [15]. Ribosomal depletion methods do not rely on the poly(A) tail and typically provide more uniform coverage along the entire transcript length [16] [14].

4. Which method should I use for degraded RNA samples, like those from FFPE tissue? Ribosomal depletion is the strongly recommended method for degraded samples such as FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) [13] [17] [14]. Since RNA fragmentation in these samples can destroy the poly(A) tail, poly(A) enrichment is highly inefficient and will result in very low yield and extreme 3' bias. Ribosomal depletion successfully removes rRNA regardless of poly(A) tail integrity, making it robust for compromised sample types [13] [14].

5. My study involves a non-model organism. Which method is more suitable? The choice depends on your target organisms. For eukaryotic organisms, poly(A) enrichment can be effective if you are only interested in polyadenylated mRNA. For prokaryotic organisms (bacteria), which largely lack poly(A) tails, ribosomal depletion is the only viable option [12] [13]. Furthermore, the efficiency of commercial ribosomal depletion kits can vary significantly between species, so it is critical to use a kit validated for your specific organism [18] [15].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Alignment Rates

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Ribosomal RNA Contamination | Check the alignment report for the percentage of reads mapping to rRNA sequences. | For rRNA-depletion protocols: Verify the kit's compatibility with your species [18] [15]. Ensure RNA is not degraded (RIN >7) before depletion [16]. For poly(A) protocols: Confirm high RNA integrity (RIN ≥8); degradation prevents poly(A) tail binding [12] [13]. |

| High Adapter Contamination | Use QC tools (e.g., FastQC) to detect overrepresented adapter sequences. | Optimize the library purification steps to remove excess adapters. Use bead-based size selection (e.g., SPRI beads) to clean up the final library and remove adapter dimers [12]. |

| Incorrect Reference Genome | Verify the species and build of the reference genome and annotation file used for alignment. | Re-align using the correct reference genome. Ensure the annotation (GTF/GFF file) matches the genome build. |

Symptom: Low Exonic Mapping Rate

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Expected Signal from rRNA-depletion | Compare your exonic mapping rate (~20-46%) to expected ranges [13] [14]. | This is characteristic of the method. Sequence deeper to achieve desired exonic coverage. For mRNA-focused studies, consider switching to poly(A) enrichment if sample quality permits. |

| Intronic Reads from Pre-mRNA | Check alignment for a high proportion of reads mapping to intronic regions. This is a known feature of rRNA-depletion [16] [13]. | If studying mature mRNA, bioinformaticially filter for exon-junction spanning reads. If the goal is gene-level expression, tools like RSEM that account for pre-mRNA can be used [16]. |

| Genomic DNA Contamination | Check for even, low-level coverage across intronic and intergenic regions, and a lack of reads spanning exon-exon junctions. | Treat your RNA sample with DNase I during the RNA extraction or purification step [12]. |

Symptom: Strong 3' Bias

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inherent to Poly(A) Selection | Use tools like RSeQC to generate a gene body coverage plot. Observe a sharp increase in read coverage at the 3' end of transcripts. | For standard gene expression, this may be acceptable. For isoform analysis, use rRNA depletion. For poly(A) protocol, optimize first-strand synthesis by using a mix of oligo(dT) and random hexamers [12]. |

| RNA Degradation | Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN); a low score (<7) indicates degradation. | Use high-quality RNA (RIN ≥8) for poly(A) enrichment. For degraded samples, switch to a ribosomal depletion protocol [13]. |

Comparative Data at a Glance

The following table summarizes key quantitative differences between the two library preparation methods that directly impact mappability and experimental design.

Table 1: Performance Comparison Affecting Mappability [13]

| Feature | Poly(A) Enrichment | Ribosomal RNA Depletion |

|---|---|---|

| Usable Exonic Reads (Blood) | ~71% | ~22% |

| Usable Exonic Reads (Colon) | ~70% | ~46% |

| Extra Reads Needed for Same Exonic Coverage | Baseline | +220% (blood), +50% (colon) |

| Typical 5'-3' Coverage Bias | Pronounced 3' bias | More uniform |

| Recommended RNA Integrity Number (RIN) | ≥ 8 [12] | ≥ 7 [16] (works on degraded/FFPE) [13] |

| Key RNA Types Captured | Mature, polyadenylated mRNA | Coding & non-coding RNA (lncRNA, snoRNA), pre-mRNA [16] [13] |

Experimental Workflows

The diagrams below outline the standard laboratory workflows for each method, highlighting the key steps that influence the final composition of mappable reads.

Key Steps & Impact on Mappability:

- Total RNA Extraction & QC: The requirement for high-quality RNA (RIN ≥8) is critical. Degraded RNA will result in failed poly(A) selection and poor mappability [12] [13].

- Poly(A) Enrichment: This is the selectivity step. Oligo(dT)-coated magnetic beads bind to and pull down RNA molecules with poly(A) tails, actively excluding rRNAs and non-polyadenylated non-coding RNAs. This is why the resulting library is highly enriched for exonic reads [12] [13].

- cDNA Library Prep: The use of oligo(dT) primers for reverse transcription is a major contributor to 3' bias, as synthesis starts at the poly(A) tail [12].

Key Steps & Impact on Mappability:

- rRNA Depletion: This is a subtraction step. Species-specific DNA probes hybridize to rRNA sequences, and the enzyme RNase H is used to digest the RNA in these RNA-DNA hybrids [19] [15]. The efficiency of this step is paramount; incomplete depletion will leave high levels of rRNA, drastically reducing the mappable fraction of your library [18] [14].

- Broader Transcriptome Capture: Because this method does not positively select for a specific feature (like a tail), it retains all non-rRNA molecules. This includes pre-mRNA (leading to intronic reads) and a wide array of non-coding RNAs, which explains the lower exonic mapping rate [16] [13].

- Random Hexamer Priming: This priming method during reverse transcription leads to more uniform coverage across the entire transcript length, avoiding the 3' bias seen in poly(A)-based methods [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for RNA-Seq Library Preparation

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Consideration for Mappability |

|---|---|---|

| Oligo(dT) Magnetic Beads | Captures polyadenylated RNA from total RNA. | Core of poly(A) enrichment. Batch quality and binding efficiency directly impact mRNA yield. [12] |

| Ribosomal Depletion Kits | Removes ribosomal RNA via probe hybridization. | Critical: Must be validated for your specific organism. Poor species-specificity leads to high rRNA carryover and low mappability. [18] [15] |

| RNase H | Enzyme that degrades RNA in RNA-DNA hybrids. | Used in many ribosomal depletion protocols to specifically digest rRNA after probe hybridization. [19] [15] |

| DNase I | Degrades contaminating genomic DNA. | Prevents gDNA reads from aligning to intergenic regions, improving exonic mapping rates. [12] |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase | Amplifies the final cDNA library by PCR. | Minimizes PCR errors and duplicate reads, ensuring accurate and non-biased representation of transcripts. [12] |

| SPRI Beads | Performs size selection and cleanup of libraries. | Removes adapter dimers and short fragments that would otherwise become un-mappable sequencing reads. [12] |

How Sample Quality (RIN) and RNA Degradation Skew Alignment Outcomes

FAQs

What is the RNA Integrity Number (RIN) and why is it critical for RNA-Seq?

The RNA Integrity Number (RIN) is a standardized score from 1 to 10 that assesses the quality of an RNA sample, with 10 representing perfectly intact RNA and 1 representing completely degraded RNA [20] [21]. It is a crucial pre-analytical metric because it directly predicts the success and accuracy of your RNA-Seq experiment. High-quality RNA (typically RIN ≥ 7) is a prerequisite for obtaining reliable gene expression data, as degradation introduces significant biases that skew alignment outcomes and quantitative measurements [4] [22] [23].

How does RNA degradation specifically lead to poor alignment rates?

RNA degradation negatively impacts alignment rates through several key mechanisms:

- Loss of Unique Mapping Regions: Degraded RNA fragments lose their 5' ends. When these short, 3'-biased fragments are sequenced, they are more likely to map to multiple locations in the genome (multi-mapping reads), which are often discarded from unique alignment counts [24] [23].

- Increase in Intergenic Reads: As transcripts break down, the resulting fragments may not align confidently to known exonic regions, leading to an increase in reads that map to intergenic regions and a corresponding decrease in the percentage of reads aligning to genes [23].

- Reduced Library Complexity: Degraded samples have a lower diversity of RNA fragments. This leads to a loss of library complexity, meaning a smaller number of unique molecules are sequenced, further reducing the effective number of aligned reads that provide useful biological information [24].

My RNA is degraded (RIN < 7). Can I still use it for RNA-Seq?

Yes, but it requires careful planning in both library preparation and data analysis.

- Switch Library Prep Kits: Do not use standard poly(A) enrichment kits, as they rely on an intact poly-A tail, which is often missing in degraded fragments. Instead, use kits designed for degraded RNA that employ random priming for cDNA synthesis, such as SMART-Seq or xGen Broad-range [25]. These methods can generate libraries from fragmented RNA.

- Employ rRNA Depletion: If possible, use ribosomal RNA (rRNA) depletion protocols instead of poly(A) selection. This approach does not depend on an intact 5' end or poly-A tail and has been shown to perform better with degraded samples [4] [22] [25].

- Use Degradation-Aware Data Analysis: Implement bioinformatic tools like DegNorm that can normalize read counts for gene-specific degradation patterns, thereby correcting for this bias in downstream differential expression analysis [26].

What are the best methods to normalize data from samples with variable RIN scores?

Standard global normalization methods (e.g., TMM in edgeR, median-of-ratios in DESeq2) are often insufficient to correct for degradation biases because degradation is not uniform across all transcripts [24] [26]. Superior approaches include:

- Explicit Modeling with RIN: Incorporate the RIN score as a covariate in a linear model framework during differential expression testing. This can account for a significant portion of the degradation-induced variation [24].

- Degradation-Specific Normalization: Use specialized tools like DegNorm, which performs normalization on a gene-by-gene basis by estimating a degradation index from read coverage patterns, simultaneously controlling for sequencing depth [26].

Troubleshooting Guide: Poor Alignment Rates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Poor RNA Quality (Low RIN)

- Solution: Always check RNA quality using an Agilent Bioanalyzer, TapeStation, or similar system before library prep. A low RIN (<7) indicates degradation. If possible, re-extract RNA from the source material, ensuring rapid stabilization at collection (e.g., using RNALater) and proper storage at -80°C [4] [27].

- Cause: Incorrect Library Prep Method for Sample Quality

- Solution: For low-RIN samples, switch from a poly(A)-enrichment protocol to an rRNA-depletion protocol or a random-primed library prep kit [25].

- Cause: Contamination

- Solution: Check RNA purity via Nanodrop (260/280 ratio ~2.0). DNA or protein contamination can inhibit library prep. Treat samples with DNase I. Use RNase-free reagents and techniques to prevent RNA degradation during handling [27].

Symptom: High rates of multi-mapping reads and reads mapping to intergenic regions.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Transcript Fragmentation from Degradation

Symptom: Strong 3' Bias in read coverage across transcripts.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Partial RNA Degradation

- Solution: In partially degraded samples, the 5' ends of transcripts are lost first. Oligo-dT based library prep will then only capture the 3' ends of these fragments, resulting in severe 3' bias. This bias confounds isoform-level analysis and quantification. The solution is to use random-primed library prep methods for such samples [23] [25].

Key Experimental Data and Protocols

Quantitative Impact of RIN on RNA-Seq Output

The following table summarizes key findings from controlled studies on the effects of RNA degradation.

| Metric | Impact of Decreasing RIN | Experimental Context | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mapping Efficiency | Significant decrease in uniquely mapped reads and reads mapped to genes. | PBMC samples stored at room temperature for 0-84 hours (RIN 9.3 to 3.8). | [24] |

| Principal Component | RIN (PC1) explains 28.9% of variation in gene expression data. | PBMC degradation time-course. | [24] |

| Library Complexity | Slight but significant loss of library complexity in degraded samples. | PBMC degradation time-course. | [24] |

| Gene Expression (RPKM) | RPKM values are positively correlated with RIN; low RIN samples show lower RPKM. | Analysis of degraded RNA samples. | [23] |

| Spike-in Control Reads | Proportion of exogenous spike-in reads increases significantly as RIN decreases. | PBMC degradation time-course with non-human RNA spike-in. | [24] |

| 3' Bias | Increased bias towards the 3' end of transcripts in poly(A)-selected libraries. | Analysis of degraded RNA in mRNA-seq protocols. | [23] |

Protocol: Evaluating Library Prep Kits for Degraded RNA

A 2024 study systematically compared RNA-Seq methods using artificially degraded RNA from human induced pluripotent stem cells (hiPSC) [25].

Objective: To determine the best RNA-Seq library preparation method for degraded RNA samples. Sample Preparation: Total RNA from hiPSC was artificially degraded. The performance of kits was compared against a Standard poly(A)-capture RNA-Seq method using the original, undegraded RNA. Methods Compared:

- Standard: Poly(A) capturing with Oligo dT beads.

- SMART-Seq: Uses random primers (N6) and template-switching technology.

- xGen Broad-range: Uses random primers and Adaptase technology.

- RamDA-Seq: Uses not-so-random (NSR) and Oligo dT primers.

Key Findings Table:

| Method | Correlation with Standard (on undegraded RNA) | Performance with Degraded RNA | Key Advantage for Degraded RNA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard (PolyA) | Benchmark | Poor (not recommended) | N/A | |

| SMART-Seq | Moderate (R=0.833) | Good (best with rRNA depletion) | Effective with low-input and degraded RNA. Detects non-coding RNAs. | [25] |

| xGen Broad-range | Moderate (R=0.878) | Moderate | Uses random primers, better than PolyA. | [25] |

| RamDA-Seq | High (similar to Standard) | Poorer performance | Performs well on intact, low-input RNA but performance decreases with degradation. | [25] |

Conclusion: For degraded RNA samples, SMART-Seq with an added rRNA depletion step was identified as the most robust method, outperforming other random-primed and standard protocols [25].

Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Kit | Function | Use Case for Degraded RNA | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMART-Seq v4 Ultra Low Input RNA Kit | Library prep using random priming and template-switching. | Ideal for both low-input and degraded RNA samples. | [25] |

| xGen Broad-range RNA-Seq Kit | Library prep using random priming and Adaptase technology. | An alternative for degraded RNA where poly(A) selection fails. | [25] |

| Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit | Depletes ribosomal RNA (rRNA) from total RNA. | Superior to poly(A) selection for degraded samples as it is not dependent on an intact poly-A tail. | [4] [22] |

| QIAseq FastSelect | Rapidly removes rRNA from RNA samples. | Can be combined with other kits (e.g., SMART-Seq) to improve performance by increasing the proportion of informative reads. | [27] |

| RNALater | Tissue RNA Stabilization Solution. | Preserves RNA integrity at the moment of sample collection during fieldwork or clinical sampling, preventing ex vivo degradation. | [24] |

Diagrams

RNA Degradation Impact on Sequencing

Solution Pathway for Degraded RNA

Building a Robust RNA-Seq Workflow: Tool Selection and Experimental Design for High Mapping Rates

Within the context of troubleshooting poor alignment rates in RNA-Seq data research, selecting an appropriate spliced alignment tool is a critical first step. The aligner you choose directly impacts the accuracy and efficiency of your entire downstream analysis. This guide provides a technical comparison of three common spliced aligners—STAR, HISAT2, and GSNAP—to help you make an informed decision and diagnose alignment issues.

FAQs: Your Spliced Alignment Questions Answered

Q1: What are the key performance differences between STAR, HISAT2, and GSNAP?

The choice of aligner involves a trade-off between speed, accuracy, and computational resources. Based on independent benchmarking studies, the performance characteristics of these tools are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Spliced Aligners

| Aligner | Best-Performing Scenario | Speed (Relative) | Memory Usage | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STAR | High accuracy for base, read, and junction levels [28] | Medium [29] | High [30] | High junction discovery accuracy, suitable for draft genomes [28] [30] |

| HISAT2 | Standard RNA-seq analyses with speed constraints [31] | Very High [29] [31] | Low [30] | Extremely fast with low resource consumption [31] |

| GSNAP | Data with high polymorphism/variation [28] [32] | Medium [32] | Medium | High recall in challenging (high-error) datasets [28] |

Q2: How does aligner accuracy vary with data quality?

The performance of an aligner can change significantly when dealing with data that has high error rates or genetic variations. A comprehensive simulation-based benchmarking study evaluated aligners across different complexity levels [28]:

- T1 (Low Complexity): Similar to aligning to the reference human genome. Most tools, including HISAT2, perform well.

- T3 (High Complexity): Features high polymorphism and error rates. Here, performance diverges sharply. GSNAP and STAR were among the few tools that maintained a base-level recall above 50% on both human and malaria genomes, demonstrating their robustness. HISAT2's performance was more comparable to TopHat2 in these demanding scenarios, indicating it may struggle with highly polymorphic data or low-quality reads [28].

Q3: I am getting low alignment rates (~40%) with HISAT2. What should I do?

Low alignment rates are a common problem. The following workflow outlines a systematic approach to diagnose and resolve this issue.

Step 1: Verify Data Quality and Content A primary suspect for low alignment rates is the presence of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination. If your library prep was supposed to be rRNA-depleted but still yields low rates, check for rRNA [33].

- Action: Take a sample of unmapped reads and BLAST them against human rDNA repeats. A high percentage of hits indicates a library prep issue.

Step 2: Check Data Integrity and Parameters

- Strandedness: Using the wrong strandedness parameter can halve your alignment rate. Test your data with both stranded and unstranded parameters to see if the rate improves [33].

- Quality Score Scaling: Ensure your FASTQ files have the correct quality score encoding (e.g., Sanger vs. Illumina 1.8). An incorrect format can severely impact alignment [34].

Step 3: Inspect Your Input Data and Preprocessing

- Over-trimming: Aggressive adapter or quality trimming can remove too much sequence, leaving insufficient information for the aligner to map the read reliably. Try a test run with little to no trimming [34].

- Fragment Size: If you are sequencing short fragments (e.g., 75-100bp), the aligner's default "minimum anchor" settings for splice junctions might be too high. You can try over-trimming reads to a shorter length (e.g., 50bp) as a diagnostic test, though this is not ideal for final analysis [33].

Step 4: Consider an Alternative Aligner If you have verified your data and parameters, the issue may lie with the aligner's performance for your specific data type. As per benchmarking studies, HISAT2 can underperform compared to STAR and GSNAP on more complex or variable datasets [28] [32]. Re-running your analysis with STAR or GSNAP can often yield a significantly improved alignment rate [30].

Table 2: Key Resources for RNA-seq Alignment Benchmarking

| Resource Name | Type | Function in Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| wgsim | Read Simulator | Generates synthetic sequencing reads from a reference genome for controlled aligner testing [32]. |

| FastQC | Quality Control Tool | Provides an initial report on read quality and can identify issues like adapter contamination or unusual base composition. |

| SAMtools | Utility | Converts SAM files to BAM format, sorts, and indexes alignments for downstream analysis [32]. |

| featureCounts | Quantification Tool | Counts the number of reads mapping to genomic features (e.g., genes) from the aligned BAM files, used to assess alignment utility [32]. |

| Arabidopsis thaliana (TAIR10) | Reference Genome | A well-annotated plant genome often used in benchmark studies for method validation [32]. |

Experimental Protocols: How to Benchmark Aligners

To objectively compare aligners like STAR, HISAT2, and GSNAP on your own system or for a specific organism, follow this simulation-based benchmarking protocol adapted from published methodologies [28] [32].

1. Generate Synthetic Reads:

- Use a simulator like

wgsimto generate paired-end reads from your reference genome and transcriptome. - Create datasets with different levels of complexity (e.g., "perfect" reads, reads with a 0.001 SNP rate, and reads with a 0.01 SNP rate) to test robustness [32].

- Example Command:

2. Execute Alignment:

- Align the simulated reads with each aligner (STAR, HISAT2, GSNAP) using both default and optimized parameters. Ensure you provide the same annotation (GTF file) to all.

- Example HISAT2 Command:

- Example GSNAP Command:

3. Process and Quantify Alignments:

- Convert SAM files to BAM format using

samtools. - Use

featureCountsto assign reads to genes. - Example Command:

4. Analyze Results: Compare the outputs of the aligners using the following key metrics, which can be structured in a summary table:

- Overall Alignment Rate: The percentage of input reads that were successfully mapped.

- Junction-Level Accuracy: The percentage of known splice junctions that were correctly identified. Studies show STAR and GSNAP often excel here, especially with short anchors or unannotated junctions [28].

- Base-Level Recall: The fraction of all simulated bases that were aligned correctly. GSNAP and STAR show high recall even in complex scenarios [28].

- Runtime and Memory Usage: Record the time and memory required for each aligner to complete the task. HISAT2 typically leads in speed [29] [31].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My RNA-Seq data has a low overall alignment rate (~40%), even though my sequencing data is high quality. What are the primary causes related to the reference genome?

A1: A low alignment rate can often be traced to issues with the reference genome itself. The main culprits are:

- Genome Contamination: The assembly may contain sequences from other organisms, cloning vectors, or adapters, which prevents your reads from mapping to the intended genome [35].

- Misassembly: Errors in the genome assembly, such as incorrect joins or rearrangements, mean the reference does not accurately represent your sample's actual genome structure [35].

- Incomplete Gene Annotation: If the gene annotation lacks critical transcripts or isoforms, RNA-Seq reads originating from those transcripts will have nowhere to map, leading to quantification failures [36] [37].

- High Repetitive Content: A high frequency of repeat sequences in the genome can cause a large number of reads to map to multiple locations, which are sometimes filtered out or reported as non-unique alignments, adversely affecting the overall mapping rate [36].

Q2: How does the choice of gene annotation database directly impact my RNA-Seq quantification results?

A2: The gene annotation database you select defines the "universe" of genes and isoforms that can be quantified. Using different annotations can lead to significant variation in your results because [38]:

- Complexity Varies: Annotations have vastly different numbers of genes and isoforms per gene. A more complex annotation (e.g., AceView) may resolve more specific splice variants but can also increase ambiguous mapping. A more conservative annotation (e.g., RefSeq) may offer clearer mapping at the cost of missing rare isoforms [38].

- Quantification Accuracy Changes: Studies comparing RNA-Seq results to qRT-PCR data have found that more complex genome annotations can lead to higher quantification variation [38].

- Coverage Differs: The total genomic territory covered by annotated features (genes, exons) differs between databases, directly influencing how many of your reads can be assigned to a feature [38].

The table below illustrates the variation across six common human genome annotations.

| Genome Annotation | Number of Genes | Number of Isoforms | Average Isoforms per Gene | Gene Base Coverage (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AceView Genes | 72,376 | 259,426 | 3.58 | 52.93% |

| Ensembl Genes | 53,970 | 183,011 | 3.39 | 49.78% |

| H-InvDB Genes | 43,893 | 236,861 | 5.40 | 45.09% |

| Vega Genes | 44,880 | 158,835 | 3.54 | 48.36% |

| UCSC Known Genes | 30,355 | 77,080 | 2.54 | 43.09% |

| RefSeq Genes | 24,016 | 41,250 | 1.72 | 39.39% |

Table 1: Comparison of Human Genome Annotations. Gene base coverage is the total length of annotated genes as a percentage of the genome length [38].

Q3: What is the significance of "unplaced contigs" in a reference genome, and how should I handle them in my RNA-Seq analysis?

A3: Unplaced contigs are sequences that are known to belong to a species but could not be confidently assigned to a specific chromosome. They represent important genomic regions that would otherwise be missing from your analysis.

- Significance: Including unplaced contigs is crucial for a comprehensive analysis. Ignoring them can lead to a significant loss of mappable reads, as you are effectively excluding a portion of the genome, which will artificially lower your alignment rate and bias quantification [38].

- Handling: Always use the most complete version of the reference genome available, which often includes files labeled as "primary assembly" plus "unplaced contigs," or a "toplevel" assembly that incorporates all sequences [38] [36]. When building a alignment index with tools like HISAT2, ensure you include the file containing these unplaced sequences.

Q4: What are the key quality metrics for a reference genome that can predict its suitability for RNA-Seq analysis?

A4: Beyond the standard N50 contiguity statistic, several key metrics can indicate genome quality for RNA-Seq [36]:

- Alignment-Based Mapping Rate: The percentage of RNA-Seq reads that successfully map to the genome. This directly reflects how well the genome sequence matches your data [36].

- Quantification Success Rate: The percentage of mapped reads that can be unambiguously assigned to annotated genes. This depends heavily on the quality and completeness of the gene annotation [36].

- BUSCO Completeness: Measures the presence of universal single-copy orthologs. While often high in published genomes, it is a standard check for gene space completeness [36].

- Repeat Element Content: A high percentage of repetitive elements can lead to a high rate of multi-mapping reads, complicating quantification [36].

The following table summarizes effective indicators for evaluating genome and annotation quality from a benchmark of 114 species [36].

| Evaluation Aspect | Indicator Name | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Genome | Mapping Rate | Percentage of RNA-Seq reads that align to the genome. |

| Multiple Mapping Rate | Percentage of reads that align to multiple genomic locations. | |

| Genome Contiguity (N50) | Length of the contig/scaffold such that 50% of the assembly is in contigs of this size or longer. | |

| Repeat Element Content | Percentage of the genome identified as repetitive sequences. | |

| Gene Annotation | Quantification Success Rate | Percentage of mapped reads that can be uniquely assigned to annotated features. |

| Transcript Diversity | The number and variety of transcripts annotated per gene. | |

| Annotation Base Coverage | Total length of annotated features (e.g., genes) as a percentage of the genome length. |

Table 2: Key Quality Indicators for Reference Genomes and Annotations [36].

Troubleshooting Guide: A Step-by-Step Workflow for Poor Alignment Rates

This workflow helps you systematically diagnose and address the root causes of low alignment rates in your RNA-Seq experiment.

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting Low Alignment Rate

Protocol 1: Investigating Unmapped Reads

- Extract Reads: Use

samtoolsto extract read pairs where both ends failed to align to the reference genome. - BLAST Analysis: Randomly select a subset (e.g., 1000) of these unmapped reads and run a BLAST search against the NT database at NCBI.

- Interpret Results:

- rRNA Hits: A significant number of reads matching ribosomal RNA suggests inadequate rRNA depletion during library preparation [33].

- Contaminant Hits: Reads matching bacteria, fungi, or other organisms indicate sample contamination [35] [33].

- Target Species Hits: If reads match your target species but not the reference, it strongly indicates a problem with the reference genome, such as poor sequence quality, misassembly, or missing regions [35] [36].

Protocol 2: Evaluating Gene Annotation Quality for Your Species

- Acquire Annotations: Download the latest gene annotation files (.gtf or .gff) from RefSeq, Ensembl, and other specialized databases for your organism.

- Calculate Basic Statistics: Use scripts or tools like

gffreadto compute key metrics:- Total number of protein-coding genes.

- Total number of transcripts (isoforms).

- Average number of isoforms per gene.

- Check for Key Non-Coding RNAs: Ensure the annotation includes crucial non-coding RNAs (tRNAs, rRNAs) which are hallmarks of a more complete annotation [37].

- Compare to Benchmarks: Consult benchmark studies if available for your organism or related species to see how your chosen annotations compare in terms of gene count and completeness [36].

Diagram 2: Annotation Complexity Trade-off

| Resource Type | Name | Function / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| Genome Annotations | RefSeq Genes [38] | Combines automated pipeline with manual curation; conservative. |

| Ensembl Genes [38] | Integrates automated annotation, manual curation, and CCDS. | |

| AceView Genes [38] | Comprehensive, evidence-based annotation from full-length cDNA. | |

| Alignment Tools | HISAT2 [36] | Fast and sensitive spliced alignment for RNA-Seq data. |

| Omicsoft Sequence Aligner (OSA) [38] | Spliced aligner with high sensitivity and low false positives. | |

| Quality Assessment | BUSCO [36] | Assesses genome/completeness based on evolutionarily informed genes. |

| FastQC [36] | Provides quality control reports for raw sequencing data. | |

| SAMtools [36] | Utilities for processing and analyzing aligned sequencing data. | |

| Data Repositories | NCBI SRA / ENA [38] [37] | Archives raw sequencing data for downloading or as evidence. |

| Dfam [36] | Database of repetitive DNA families for repeat masking. |

This technical support center provides FAQs and troubleshooting guides for researchers addressing poor alignment rates in RNA-Seq data analysis. The guidance is framed within the context of a broader thesis on troubleshooting alignment issues.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. My RNA-Seq data has a low alignment rate (~40%). What could be the cause? A common cause of low alignment rates, even with careful trimming, is the presence of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) contamination. This can occur even when using rRNA depletion kits [33]. To investigate:

- Check for rRNA: Align a subset of your unmapped reads to a database of human rDNA repeats. If a significant portion aligns, your sample likely has rRNA contamination [33].

- Verify Sequence Quality: Low-quality RNA samples can lead to over-amplification of certain sequences during library prep, causing an imbalance in the final pool and reducing alignment efficiency [33].

2. Should I perform quality trimming on my RNA-Seq data? For modern sequencing data, aggressive quality trimming is often unnecessary. Most aligners can handle adapter contamination and low-quality bases by soft-clipping [39]. However, a minimal trimming approach is recommended:

- Adapter Trimming: This is crucial, especially if your library has small inserts [39].

- Light Quality Trimming: Trimming low-quality bases (e.g., Phred score < 20) can be beneficial [39].

- Avoid Over-trimming: Excessive trimming can reduce read length and potentially compromise alignment uniqueness, particularly for splice-aware aligners [34].

3. My FastQC report shows "Failed" for "Per base sequence content." Is this a problem? For RNA-Seq data, a "FAIL" in the "Per base sequence content" module for the first 10-12 bases is normal and expected. It is caused by non-random priming during the RNA-seq library preparation process and does not indicate a problem with your data [40].

4. How do I decide on a minimum length for reads after trimming? A common practice is to keep reads that are at least 80% of the original read length [39]. For standard differential expression analysis, reads of 50 base pairs or longer are generally considered sufficient [39]. See the table below for a summary of recommendations.

Table 1: Minimum Read Length Recommendations After Trimming

| Analysis Type | Recommended Minimum Length | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| General RNA-seq / DGE | 50 bp or longer [39] | Longer reads help with unique alignment. |

| Standard Guidance | 80% of original read length [39] | Balances read retention and quality. |

| Small RNA-seq | Default of 20 bp (e.g., in Trim Galore) [39] | Appropriate for very short RNA species. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Low Alignment Rates

A low overall alignment rate (e.g., below 60-70%) can stem from various issues. Follow this logical workflow to diagnose and address the problem.

Detailed Steps:

Initial Quality Control:

- Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files to get a baseline quality assessment [40].

- Pay close attention to the "Adapter Content" and "Overrepresented sequences" modules. High levels indicate the need for trimming.

Perform Targeted Trimming:

- If adapter content is high, use a tool like

fastporTrimmomaticto remove adapter sequences. - Use a light quality trim (e.g., Phred score < 20) and set a minimum length of 80% of your original read length [39].

- For data from NovaSeq/NextSeq instruments, enable polyG tail removal in

fastp[41]. For mRNA-Seq data, polyX trimming (e.g., polyA) can be beneficial [42].

- If adapter content is high, use a tool like

Investigate Contamination:

- If the alignment rate remains low after trimming, rRNA contamination is a likely culprit [33].

- Align the unmapped reads to a reference of rRNA sequences. This can be done by extracting unmapped reads from your BAM file and using BLAST or a quick alignment to an rDNA database.

- If a large fraction of reads are rRNA, review your laboratory's RNA extraction and rRNA depletion protocols. The Bioanalyzer profile of your input RNA should show intact RNA without significant rRNA peaks [33].

Guide 2: Configuring Trimming Tools for RNA-Seq Data

This guide provides specific parameters for fastp and Trimmomatic to address common RNA-Seq data issues.

Using fastp:

fastp is an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Below is a command template with recommended options for RNA-seq [41].

Table 2: Key fastp Parameters for RNA-Seq Troubleshooting

| Parameter | Function | Rationale for RNA-Seq |

|---|---|---|

--trim_poly_x |

Trims polyX tails (e.g., polyA) | Removes unwanted polyA tails from mRNA, improving runtime for downstream alignment and variant calling [42]. |

--trim_poly_g |

Trims polyG tails | Common in NovaSeq/NextSeq data; removal improves data quality [41]. |

--cut_front --cut_tail --cut_window_size=4 --cut_mean_quality=20 |

Sliding window quality trimming | Performs a light quality trim, removing low-quality bases from the 5' and 3' ends similar to Trimmomatic but faster [41]. |

--length_required=50 |

Minimum length filter | Discards reads that are too short after trimming, ensuring reads are long enough for reliable alignment [39]. |

Using Trimmomatic: For Trimmomatic, a typical command for paired-end data would be [43]:

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Library Preparation and QC

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Nextera / Illumina Adapters | Oligonucleotide sequences ligated to fragments for sequencing on Illumina platforms. Specific sequences (e.g., TruSeq3-SE.fa) must be provided to trimming tools for adapter removal [43] [44]. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Kits to remove ribosomal RNA, enriching for mRNA and other RNA types. Inefficient depletion is a major cause of low alignment rates [33]. |

| Bioanalyzer / TapeStation | Instruments for assessing RNA integrity (RIN) before library prep. Low-quality input RNA is a primary source of poor sequencing results [33]. |

| UMI (Unique Molecular Identifier) | Short random nucleotide sequences used to tag individual RNA molecules before PCR amplification. fastp can preprocess UMI-enabled data to correct for PCR duplicates [41]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the fundamental difference between alignment-based tools and tools like Salmon and Kallisto?

Alignment-based tools (e.g., STAR, HISAT2) perform spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to the genome. Their primary job is to find the exact base-to-base location where each read originated, outputting a BAM file of coordinates. Quantification is often a separate, subsequent step [45].

Lightweight quantifiers (e.g., Salmon, Kallisto) bypass full alignment. They use the core idea that for quantification, you often don't need the precise alignment location—you only need to know the set of transcripts from which a read could have originated. This process, known as pseudoalignment or quasi-mapping, is what makes them so fast [45] [46]. They directly output transcript abundance estimates.

When should I choose STAR over Salmon or Kallisto, and vice versa?

The choice depends on your research goals and resources.

| Use Case | Recommended Tool | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Discovering novel transcripts/genes | STAR (or other aligners) | Alignment-based tools map to the entire genome, enabling the discovery of unannotated features. Salmon/Kallisto can only quantify against a provided transcriptome [45]. |

| Maximum speed & efficiency | Kallisto or Salmon | These tools are magnitudes faster and use less memory than traditional aligners, making them suitable for laptops or high-throughput workflows [45] [46]. |

| Advanced bias correction | Salmon | Salmon includes sophisticated models to correct for sequence-specific, positional, and GC-content biases, which can improve quantification accuracy [47]. |

| Gene-level differential expression | Either | Both pipelines work well. STAR can generate counts for gene-level analysis, and both Salmon/Kallisto estimates can be summarized to the gene level for tools like DESeq2 or edgeR [47] [45]. |

| Transcript-level differential expression | Salmon or Kallisto | These tools are designed from the ground up to handle the uncertainty of assigning reads to multiple isoforms using statistical models [45]. |

I am getting low alignment rates with STAR on total RNA-seq data. Is this normal?

Low mapping rates can occur with total RNA-seq (as opposed to poly-A selected data) and are often due to a high fraction of ribosomal RNA (rRNA) reads [2]. Ribosomal RNAs are present in numerous copies across the genome, causing many reads to map to multiple locations (multi-mapping reads). By default, STAR considers a read unmapped if it aligns to more than 10 loci, which can discard these rRNA reads [2].

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Confirm the cause: Check the aligner's log file for the number of multi-mapping reads. A high percentage suggests rRNA is the issue.

- Adjust alignment parameters: You can increase the number of allowed multi-mappings in STAR using the

--outFilterMultimapNmaxparameter, but this may not fully resolve the issue for downstream quantification [2]. - Use ribosomal RNA sequences: Ensure your reference includes all rRNA sequences and contigs. Sometimes, not all ribosomal repeats are placed on the primary chromosomes [2].

- Check for degradation: A high number of reads classified as "too short" by STAR can indicate RNA degradation, as short fragments are difficult to map uniquely [2].

My quantification results from Salmon and Kallisto look very different. Which one is correct?

While Salmon and Kallisto use different underlying algorithms (quasi-mapping with bias correction vs. pseudoalignment with a de Bruijn graph), multiple independent assessments have found that their results are highly concordant and nearly identical for many datasets [45] [46]. Significant differences are unusual for standard poly-A sequenced data.

If you observe large discrepancies, consider:

- Library Type Specification: Ensure you have correctly specified the library type (

-lin Salmon,---strandedin Kallisto) for both tools. - Bias Correction: By default, Salmon performs more comprehensive bias correction. Disable it in Salmon (e.g.,

--noSeqBias,--noGCBias) to see if the results become more similar to Kallisto, which might indicate a library-specific bias. - Data Source: One analysis on a single dataset found Kallisto to be slightly more accurate, while another highlighted Salmon's bias correction as an advantage. The performance can be dataset-dependent [48] [47].

Changes in alignment parameters (e.g., the number of allowed mismatches, minimum alignment score) within a wide range often have little technical impact on metrics like mapping rate or sample-sample correlation. Consequently, they may not drastically alter the top results of a differential expression analysis [3].

However, performance can "break" dramatically in difficult genomic regions, such as those with paralogs (e.g., X-Y homologous genes) or the MHC locus. In these regions, parameter choices can significantly impact the mapping and quantification of genes, potentially leading to false positives or negatives [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide: Diagnosing and Resolving Low Mapping Rates

Low mapping rates can stem from various issues. This guide helps you diagnose and fix them.

Step 1: Check the Quality of Your Raw Data

- Action: Run FastQC on your raw FASTQ files.

- What to look for: Adapter contamination, overall low quality, or overrepresented sequences (which could be rRNA).

- Solution: If issues are found, trim adapters and low-quality bases with a tool like Trim Galore! or Trimmomatic.

Step 2: Verify Your Reference and Annotations

- Action: Ensure your reference genome and annotation (GTF) files are from the same source and version. Also, confirm you are using the entire genome, including all contigs and scaffolds, not just the primary chromosomes [2].

- Solution: Download a consistent set of genome and annotation files from a source like GENCODE or Ensembl.

Step 3: Examine the Aligner's Log File The log file is the first place to look for clues. The table below interprets common issues.

| Log File Output | Potential Cause | Solutions to Try |

|---|---|---|

| High percentage of "too short" reads | RNA degradation or excessive adapter trimming. | Check RNA Integrity Number (RIN). Re-run trimming with careful parameters. [2] |

| High percentage of "multimapping" reads | Reads originating from repetitive regions (e.g., rRNA, paralogous genes). | For total RNA-seq, this is expected. Consider using --outFilterMultimapNmax in STAR to allow more alignments, but be cautious for downstream analysis. [2] |

| Low "concordant pair" alignment rate | Potential issues with library preparation or incorrect insertion size settings. | Check that the "Minimum intron size" and other relevant parameters are set correctly for your organism. |

Step 4: Inspect Mappings in a Genome Browser

- Action: Load your BAM file into a genome browser like IGV.

- What to look for: Look at the mapping patterns for a gene you expect to be expressed. Check if the reads are evenly distributed or if there are unusual gaps or piles of unmapped reads. This can reveal annotation problems or other issues [45].

Guide: Selecting the Right Quantification Strategy for Your Experiment

This guide helps you choose a workflow based on your experimental goals.

Workflow Decision Diagram

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Reference Transcriptome Indexing for Salmon and Kallisto

This protocol describes how to build the necessary index files for lightweight quantifiers.

Research Reagent Solutions (In-Silico)

| Item | Function | Example Source |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Transcriptome (FASTA) | Contains the nucleotide sequences of all known transcripts. Provides the target for quasi-mapping. | Ensembl (Homo_sapiens.GRCh38.cdna.all.fa.gz) |

| Salmon Software | A tool for transcript quantification that uses quasi-mapping and selective alignment. | https://github.com/COMBINE-lab/salmon |

| Kallisto Software | A tool for transcript quantification that uses pseudoalignment and a de Bruijn graph. | https://pachterlab.github.io/kallisto/ |

Detailed Methodology:

Obtain Reference Data:

- Download a cDNA FASTA file for your organism from a database like Ensembl, GENCODE, or RefSeq.

Build the Salmon Index:

- Command:

- Flags: The

--gencodeflag is recommended for GENCODE references as it handles the parsing of transcript names appropriately. This process typically takes a few minutes [48].

Build the Kallisto Index:

- Command:

- This process is also fast but may take slightly longer than Salmon's indexing in some comparisons [48].

Protocol: Transcript Quantification and Differential Expression Analysis

This protocol covers the quantification and initial analysis steps for a paired-end RNA-seq sample.

Detailed Methodology:

Quantification with Kallisto:

Quantification with Salmon:

Downstream Analysis with Sleuth (for Kallisto) or tximport/DESeq2 (for Salmon):

- Sleuth: An R package designed for interactive analysis of Kallisto results. It uses the bootstrap data to model technical and biological variance for differential expression testing [46].

- tximport: An R method to import Salmon (or Kallisto) abundance estimates and summarize them to the gene level for use with standard differential expression packages like DESeq2 and edgeR [47] [50].

Comparison Tables

Table 1: Technical Comparison of RNA-seq Quantification Tools

| Feature | STAR (Alignment-Based) | Salmon (Lightweight) | Kallisto (Lightweight) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Function | Spliced alignment to genome [45] | Transcript quantification via quasi-mapping [47] | Transcript quantification via pseudoalignment [47] |

| Key Algorithm | Seed-and-extend with genome index [45] | Quasi-mapping / Selective alignment [49] [47] | Pseudoalignment via de Bruijn graph [47] |

| Output | BAM file (genomic coordinates) [45] | Transcript-level counts/TPM [45] | Transcript-level counts/TPM [45] |

| Speed | Slower (benchmark: ~2.6x slower than Kallisto) [45] | Very Fast [48] [47] | Extremely Fast (often fastest) [48] [47] |

| Memory Usage | High (can be 15x more than Kallisto) [45] | Moderate [47] | Low / Memory-efficient [47] [45] |

| Bias Correction | Not inherent | Sequence, positional, and GC-bias models [47] | Basic sequence bias correction [47] |

| Novel Transcript Discovery | Yes [45] | No [45] | No [45] |

Diagnosing and Fixing Low Alignment Rates: A Step-by-Step Troubleshooting Protocol

FAQ 1: Why Are My Multi-Mapped Reads So High and How Should I Handle Them?

A: High multi-mapping rates are common in RNA-seq analysis due to the presence of duplicated sequences (e.g., paralogous genes, transposable elements, and other repeats) in eukaryotic genomes. When a read could originate from multiple locations in the genome, aligners flag it as multi-mapping. The choice of how to handle these reads directly impacts the accuracy of gene quantification [51].

Handling multi-mapped reads requires a strategy that matches your experimental goals. The table below summarizes the primary causes and recommended solutions:

| Cause of Multi-mapping | Impact on Data | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Paralogous Genes: Genes with high sequence similarity [51] | Inflated or ambiguous expression counts for specific gene families | Use quantification tools that probabilistically redistribute multi-mapped reads rather than discarding them. |

| Repetitive Elements: Transposable elements, low-complexity regions [51] | General background noise, potential misassignment of expression | Consider the biotype; tools are often specific for long RNAs (e.g., mRNAs, lncRNAs) or short RNAs [51]. |

| Embedded Genes: Genes located within introns of other genes [51] | Incorrect assignment of reads to a host gene | Employ alignment-based quantifiers that use an expectation-maximization algorithm to resolve read ambiguity. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Diagnose and Mitigate High Multi-Mapping

- Verify with Aligner Statistics: Check your aligner's output log. A high percentage of reads marked as "multiple alignments" confirms the issue. For example, one user reported that over 95% of their mapped reads had multiple alignments [34].

- Select an Appropriate Tool: Choose a quantification tool designed to handle multi-mapping reads, such as Salmon, RSEM, or Cufflinks. These tools use statistical models to assign reads to the most likely transcript of origin [51].

- Filter by Biotype: Analyze the biotypes of your highly expressed genes. Long-noncoding RNAs and messenger RNAs typically share less sequence similarity with other genes compared to biotypes encoding shorter RNAs, which may require separate analytical tools [51].

- Inspect Genomic Context: Use a genome browser to visually inspect the alignment of multi-mapped reads. This can reveal if they are concentrated in repetitive regions or span specific paralogous gene families, helping to confirm the biological basis of the multi-mapping.

Diagram: A diagnostic workflow for troubleshooting high levels of multi-mapped reads, from initial detection to resolution.

FAQ 2: What Does 'Too Short' Mean in My Alignment Report and How Can I Fix It?

A: In RNA-seq aligners like STAR, "too short" does not mean your input reads are too short. It indicates that the aligned portion of a read (or read pair) is shorter than a required threshold, leading the aligner to filter it out. This is often a symptom of suboptimal alignment parameters or issues with the read library itself [52] [53].

The following table compares scenarios and solutions for different causes of "'too short' alignments":

| Scenario | Typical Observation | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Strandedness Protocol | Paired-end mapping fails (high "% unmapped: too short"), but single-end mapping of mates works fine [53]. | Re-run alignment with the correct --outSAMstrandField setting. For reverse-complement data, use --outSAMstrandField intronMotif or reverse-complement the FASTQ files. |

| Overly Strict Alignment Filters | A large proportion of reads are filtered as "too short," even with reasonable input read lengths (e.g., 75-150 bp) [52]. | Adjust STAR's --outFilterScoreMinOverLread and --outFilterMatchNminOverLread (e.g., from default 0.66 to 0.3). |

| Data Quality or Library Prep Issues | Low alignment rates persist across different aligners and parameter settings. HISAT2 may show a high percentage of unpaired reads [52]. | Investigate library quality, check for sample contamination (e.g., rRNA), and ensure R1 and R2 files are correctly paired. |

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Resolve 'Too Short' Alignments

- Check Single vs. Paired-End Performance: A key diagnostic step is to align the forward (R1) and reverse (R2) reads separately as single-end. If single-end alignment rates are high (e.g., >85%) but the paired-end rate is very low (<1%), this strongly indicates a strandedness issue [53].

- Adjust Alignment Score Parameters: For STAR, loosen the filters controlling the minimum alignment length. The parameters

--outFilterScoreMinOverLreadand--outFilterMatchNminOverLreaddefine the minimum alignment score and matched bases as a fraction of the read length. Reducing these from the default of 0.66 to 0.3 or even 0 can rescue alignments, especially for reads spanning splice junctions [52]. Note: Setting them to 0 will include all very short alignments, which may not be desirable. - Verify Strandedness Setting: Confirm the strandedness protocol of your RNA-seq library kit. If the data are reverse-complement, inform the aligner. In STAR, using the parameter

--outSAMstrandField intronMotifcan resolve paired-end mapping for reverse-complement libraries [53]. - Investigate Data Quality: If parameter adjustments fail, extract the unmapped reads and use BLASTN on a small subset (e.g., 1000 reads) to identify their origin. This can reveal contamination (e.g., ribosomal RNA) or other issues with the library [52] [33].

Diagram: A systematic decision tree for diagnosing and fixing the root cause of "'too short' alignment" errors.

FAQ 3: How Does Strandedness Affect Alignment and How Do I Set It Correctly?

A: Strandedness in RNA-seq refers to whether the protocol preserves the original strand orientation of the transcript. Using an incorrect strandedness parameter during alignment can cause the aligner to misinterpret the relationship between the read and the genomic sequence, leading to a significant drop in concordant alignment rates, as it effectively doubles the search space for each read [33].

Experimental Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide to Determine and Set Strandedness

- Know Your Library Kit: Before analysis, review the documentation for your RNA library preparation kit. Kits from NuGEN, for example, are often directional [33].

- Empirical Verification with a Subset: If you are unsure of the protocol, empirically determine the strandedness.

- Align a subset of your reads (e.g., 100,000) to the reference genome using a tool like HISAT2, once with the

--rna-strandnessparameter set toFR(stranded, reverse-forward) and once set tounstranded. - Compare the overall alignment rates. A notably higher alignment rate with one setting over the other indicates the correct protocol.

- Align a subset of your reads (e.g., 100,000) to the reference genome using a tool like HISAT2, once with the

- Set the Parameter in Your Aligner: Use the correct parameter in your aligner based on your findings.

- HISAT2: Use

--rna-strandnessfollowed byFRorRF. - STAR: The

--outSAMstrandFieldparameter is crucial. For standard stranded libraries,--outSAMstrandField intronMotifis often used and can also help resolve paired-end mapping issues [53].

- HISAT2: Use

- Cross-Validate with IGV: After alignment, load the BAM file into a genome browser like IGV. Examine reads mapping to a known, well-annotated gene with introns. Check if the reads align only to the genomic strand that matches the gene's orientation (stranded protocol) or to both strands (unstranded protocol).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Tool | Function in Troubleshooting |

|---|---|

| STAR Aligner | A widely used splice-aware aligner for RNA-seq data. Its parameters for filtering "too short" alignments and setting strand fields are critical for diagnostics [52] [53]. |

| HISAT2 | Another popular aligner for RNA-seq. Useful for comparing alignment rates under different --rna-strandness settings to empirically determine the library protocol [33]. |

| Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) Sequence Database | A reference set of rRNA sequences. Aligning a sample of unmapped reads to this database can diagnose insufficient rRNA depletion, a common cause of low alignment rates [33]. |

| FastQC | A quality control tool for high-throughput sequence data. It helps identify adapter contamination, unusual base composition, or other sequencing artifacts that can lead to poor alignment. |

| NCBI BLAST Suite | Used to identify the origin of reads that consistently fail to align to the reference genome, helping to pinpoint contamination or reveal novel sequences [52]. |

| Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) | A visualization tool for exploring aligned genomic data. Essential for visually confirming strandedness and inspecting read mappings in problematic genomic regions [53]. |

Frequently Asked Questions

My alignment rate is low. Which key parameters should I check first? Start by checking the minimum alignment score and the maximum number of mismatches allowed. Overly stringent settings here can drastically reduce your mapping yield [3]. Also, verify that the

--sjdbOverhangparameter during genome indexing is set correctly (typically read length minus 1) [54].A large proportion of my reads are multi-mapped. Is it better to discard them or keep them? Simply discarding them can lead to significant loss of data and biased quantification, especially for genes within duplicated families [55]. It is generally better to use tools that employ probabilistic methods to re-allocate these reads among their potential origins, such as using an expectation-maximization algorithm [55].

How does gene annotation influence spliced alignment? Providing a gene annotation file (GTF/GFF) during genome indexing allows the aligner to be aware of known splice junctions. This greatly improves the accuracy of mapping spliced reads, particularly for identifying canonical intron boundaries [54]. However, be aware that this may potentially reduce the discovery of novel junctions.

My differential expression analysis seems sensitive to the aligner I used. Why? Different aligners, and even different parameters for the same aligner, can change the read counts assigned to genes. This is especially true for multi-mapped reads and reads in complex genomic regions (e.g., paralogs), which can subsequently alter the list of genes called as differentially expressed [56].

Can I use the same aligner and parameters for long-read RNA-seq data (PacBio/Oxford Nanopore)? While some short-read aligners like STAR can be adapted for long reads with modified parameters, they may not handle the high error rates optimally. For long-read technologies, aligners like GMAP are often recommended, and an initial error-correction step of the reads can significantly improve alignment accuracy [57].

Troubleshooting Guide: Improving Poor Alignment Rates

Adjust Core Alignment Parameters