Strategies for Enhancing Accuracy in De Novo Genome Assembly: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to improve the accuracy of de novo genome assembly.

Strategies for Enhancing Accuracy in De Novo Genome Assembly: A Guide for Biomedical Researchers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals seeking to improve the accuracy of de novo genome assembly. It covers foundational principles, from the evolution of sequencing technologies to the persistent challenges of repetitive regions and complex ploidy. The piece delves into modern methodological approaches, including the selection of long-read technologies and hybrid sequencing strategies, advanced assemblers, and haplotype-resolution techniques. It further offers practical troubleshooting advice for common issues and a rigorous framework for validating assembly quality through benchmarking and comparative genomics. The goal is to empower scientists to generate high-quality, reliable genomic blueprints essential for downstream applications in functional genomics and personalized medicine.

The Foundation of Accuracy: Understanding Assembly Challenges and Technological Evolution

FAQs: Long-Read Sequencing in De Novo Genome Assembly

What are the main types of long-read sequencing technologies and how do I choose? Two main technologies dominate the market: Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) HiFi sequencing and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing [1]. PacBio HiFi uses Single Molecule Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing on a chip containing millions of tiny wells, generating highly accurate reads (exceeding 99.9% accuracy) between 15,000-20,000 bases [2] [3]. ONT sequencing passes a single DNA strand through a protein nanopore, detecting changes in electrical current to determine the sequence; it can produce ultra-long reads exceeding hundreds of thousands of bases but typically has lower raw read accuracy than HiFi [2] [3]. Choice depends on your project's need for accuracy versus read length, budget, and application focus [3].

Why is long-read sequencing particularly advantageous for de novo genome assembly? Long-read sequencing immediately addresses a key challenge of short-read technologies: the inability to sequence long, repetitive stretches of DNA without fragmentation [2]. By generating reads that are thousands to tens of thousands of bases long, these technologies can span repetitive elements and complex genomic regions, providing sufficient overlap for far more contiguous and complete sequence assembly, ultimately enabling telomere-to-telomere (T2T) reconstructions [2] [4].

My long-read assembly is still fragmented. What steps can I take to improve contiguity? First, assess your input data quality and quantity. Ensure you are using High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA as input, as fragmentation at this stage cannot be recovered bioinformatically [5]. Consider increasing sequencing coverage to ensure sufficient overlap for assemblers. Secondly, evaluate and potentially switch your assembly tool. Different assemblers employ distinct algorithms (e.g., overlap-layout-consensus, graph-based) and perform variably depending on the genome and data type [6]. Benchmarking has shown that assemblers like NextDenovo and NECAT, which use progressive error correction, consistently generate near-complete, single-contig assemblies [6].

How accurate are modern long-read sequences, and can they be used without short-read polishing? The accuracy of long reads has improved dramatically. PacBio HiFi reads routinely achieve accuracies of 99.9% (Q30), making them suitable for most applications without short-read polishing [2] [3]. Recent studies on bacterial genomes have demonstrated that Oxford Nanopore sequencing with updated chemistry (R10.4.1) and basecalling models can achieve an average reproducibility accuracy of 99.9%, with results showing that short-read polishing only improved accuracy by 0.00005% [7] [8]. This supports the feasibility of long-read-only assembly pipelines.

What are the most common bioinformatic pitfalls in long-read assembly, and how can I avoid them? Common pitfalls include inadequate quality control (QC), using outdated or inappropriate tools, and misinterpreting assembly metrics. To avoid them:

- Perform rigorous QC: Use tools like LongQC or NanoPack to assess read length distribution and quality before assembly [1].

- Choose a modern, suitable assembler: Select assemblers designed for your specific long-read data type (e.g., HiFi vs. ONT). Tools like hifiasm (for HiFi data) and Flye are widely used and actively maintained [6] [4].

- Look beyond N50: While the N50 contig length measures contiguity, also assess completeness with tools like BUSCO and base-level accuracy by comparing to a reference if available [6].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Assembly Contiguity and High Fragmentation

Symptoms: Low N50 statistic, a final contig count far exceeding the expected chromosome number, and failure to span known repetitive regions [4].

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Read Length | Calculate the N50 read length of your dataset. Compare it to the size of known repetitive elements in your genome. | For ONT, optimize library prep for ultra-long reads. For PacBio, ensure you are using the appropriate library prep for longer HiFi reads [3]. |

| Inadequate Sequencing Coverage | Check the depth of coverage from your sequencing run. For de novo assembly, 20-30x coverage for HiFi and often higher for ONT is typically recommended. | Sequence to a higher depth. For ONT, note that higher coverage may be required due to lower raw read accuracy [3] [1]. |

| Suboptimal Assembler Choice | Research the primary algorithm of your assembler and its performance on similar genomes (e.g., plant, mammalian, microbial). | Switch to an assembler known for high contiguity. Benchmarking studies suggest NextDenovo, NECAT, or Flye often provide a strong balance of accuracy and contiguity [6]. |

| Low Input DNA Quality | Run genomic DNA on a pulse-field gel or fragment analyzer to confirm it is HMW and not degraded. | Optimize DNA extraction protocols to preserve HMW DNA. This is a critical, often overlooked, wet-lab factor [5]. |

Issue: Systematic Errors and Inaccurate Assemblies

Symptoms: Persistent indels in homopolymer regions, errors in coding sequences, and incorrect genotyping calls (e.g., in cgMLST) [8].

Possible Causes and Solutions:

| Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Technology-Specific Error Profiles | Map reads back to your assembly and look for systematic error patterns, such as indels in homopolymers (ONT) or random errors (older PacBio data). | For ONT, use the latest basecaller (e.g., Dorado) and the most accurate basecalling model (e.g., "sup" model). For complex genomes, consider PacBio HiFi for its higher per-read accuracy [3] [8]. |

| DNA Methylation Interference | Check if your bacterial species has known methylation systems. Analyze error rates in methylated vs. non-methylated regions. | Use methylation-aware polishing tools. For ONT, the medaka polishing tool offers models trained to account for bacterial methylation, which can reduce associated errors [8]. |

| Ineffective Polishing | Evaluate assembly accuracy before and after polishing using a tool like Merqury. | Re-polish your assembly. A single round of long-read polishing is often sufficient. Avoid multiple rounds, as this can sometimes degrade assembly quality [8]. Use a dedicated variant-aware polisher like NextPolish. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Applications

Protocol: A Basic Workflow for De Novo Genome Assembly Using Long Reads

Objective: To reconstruct a complete, high-quality genome sequence from long-read sequencing data.

Principle: Overlap-Layout-Consensus (OLC) or graph-based assembly algorithms use the long stretches of sequence from individual reads to find overlaps, build a contiguous layout, and compute a highly accurate consensus sequence [6].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- DNA Extraction & QC: Extract ultra-pure, High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA. Quality control is critical; assess DNA integrity using a Fragment Analyzer or pulse-field gel electrophoresis [5].

- Library Preparation & Sequencing: Prepare libraries according to the manufacturer's protocol (PacBio or ONT). Sequence to an appropriate coverage (e.g., >20x for HiFi, >30x for ONT).

- Basecalling (ONT-specific): Convert raw electrical signals (squiggles) to nucleotide sequences using the latest basecaller (e.g., Dorado) [1].

- Data Preprocessing:

- Quality Control: Run LongQC or NanoPack to filter out poor-quality reads and short fragments [1].

- (Optional) Read Correction: Some assemblers, like Canu, include a built-in read correction step.

- De Novo Assembly: Execute the assembly using a chosen assembler. Example with Flye:

flye --nano-raw input_reads.fastq.gz --genome-size 100m --out-dir out_flye --threads 32 - Assembly Polishing: Polish the initial assembly to correct residual errors.

- Long-read polishing: Map the original reads back to the draft assembly and run a polisher (e.g., medaka for ONT).

- Assembly QC: Evaluate the final assembly using:

- Contiguity: N50, number of contigs.

- Completeness: BUSCO to assess the presence of universal single-copy orthologs [6].

- Accuracy: Merqury to evaluate consensus quality.

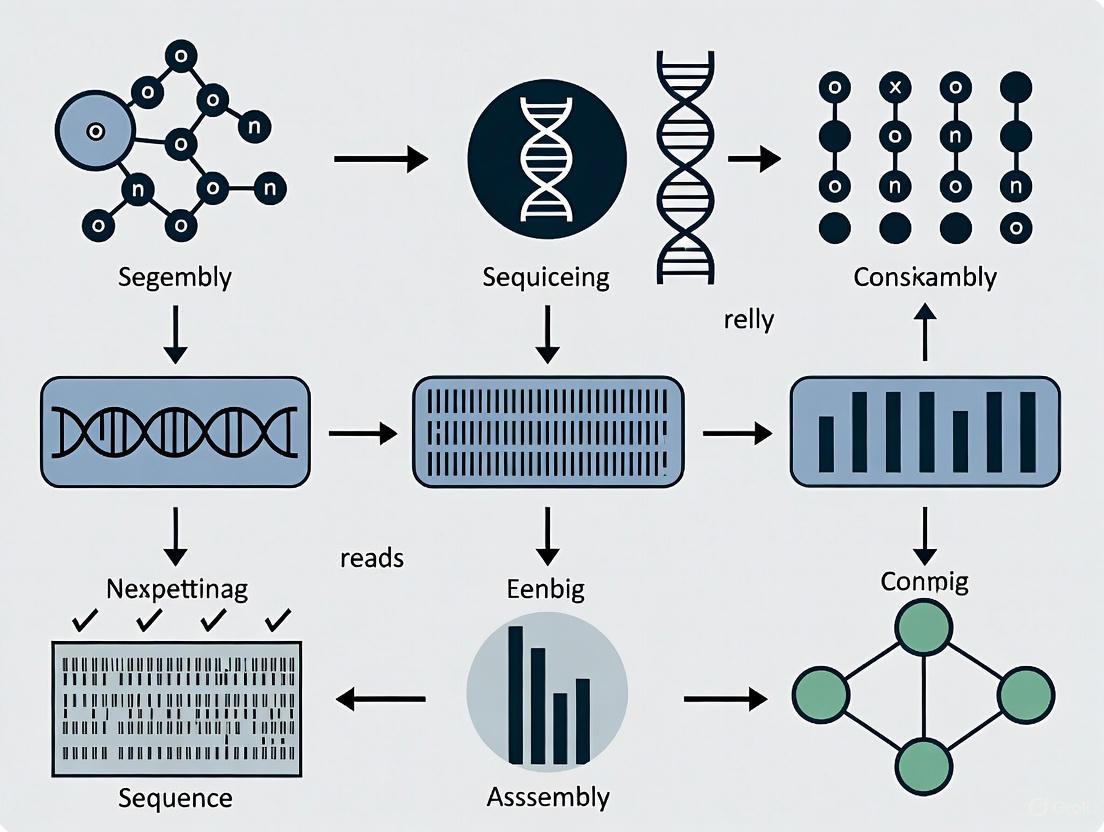

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps and decision points in this process.

Protocol: Resolving Complex Repetitive Regions

Objective: To accurately sequence and assemble long tandem repeats, such as those in centromeres and rDNA regions, which remain a key challenge [4].

Principle: Combine ultra-long sequencing reads (>100 kbp) with complementary technologies like Chromosome Conformation Capture (Hi-C) to scaffold contigs and correctly order and orient sequences across massive repeats [9] [4].

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Generate Ultra-Long Reads: For ONT, use specific library preparation kits (e.g., Ligation Sequencing Kit) optimized for ultra-long read generation.

- Perform Hi-C Library Prep: Fix the 3D chromatin architecture of cells with formaldehyde, digest with a restriction enzyme, and perform proximity ligation. Sequence the resulting library on a short-read or long-read platform.

- Assemble with Ultra-Long Reads: Use an assembler like Shasta or NECAT that is designed to handle ultra-long read data.

- Scaffold with Hi-C Data: Use a tool like YaHS to scaffold the initial assembly using the Hi-C data, creating chromosome-scale scaffolds.

- Manual Curation: Visualize the Hi-C contact maps with a tool like HiGlass to verify and correct misassemblies, particularly in repetitive regions.

| Category | Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|---|

| Wet-Lab Reagents | High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., Nanobind, MagAttract) | Preserves long DNA fragments, which is the foundational requirement for generating long reads and achieving contiguous assemblies [5]. |

| PacBio SMRTbell Prep Kit / ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit | Prepares DNA libraries in the format required for the respective sequencing platform. | |

| Hi-C Library Preparation Kit | Captures chromatin proximity data, enabling scaffolding of assemblies to chromosome scale [9]. | |

| Bioinformatics Tools | QC Tools: LongQC, NanoPack | Assess raw read quality, length distribution, and identify potential issues before computationally intensive assembly [1]. |

| Assemblers: Flye, hifiasm, NextDenovo, NECAT | Core software that performs the de novo assembly by finding overlaps between reads and building contigs. Choice is critical for success [6] [4]. | |

| Polishers: Medaka, NextPolish | Corrects small base-level errors (SNVs, indels) in the draft consensus sequence using the original sequencing reads [8]. | |

| QC & Evaluation: BUSCO, Merqury | Provides metrics on assembly completeness (BUSCO) and consensus quality (Merqury) to objectively judge the final product [6]. | |

| Computational Resources | High-Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster | Assembly is computationally intensive, requiring significant CPU and memory (e.g., hundreds of GB of RAM for a mammalian genome). |

| GPU Server (for ONT) | Accelerates basecalling and some variant calling processes, significantly reducing analysis time [3]. |

For researchers in genomics, producing a high-quality de novo genome assembly is foundational for all downstream biological interpretation, from gene annotation to comparative genomics and drug target identification [10]. The quality of a reference genome directly impacts the reliability of scientific conclusions, making rigorous assembly assessment critical. Modern genome evaluation moves beyond simple contiguity to embrace a three-dimensional framework defined by the "3 Cs": Contiguity, Completeness, and Correctness [10].

This technical guide provides troubleshooting support and methodological details to help researchers accurately measure and improve these three essential metrics within their genome assembly projects, ensuring the production of reference-grade genomes suitable for advanced research and drug development applications.

Core Concepts: Understanding the 3 Cs

Contiguity

What is measured: Contiguity assesses how fragmented or connected an assembly is, reflecting the ability to reconstruct long, continuous DNA sequences from shorter sequencing reads.

Primary Metric:

- Contig N50: The length cutoff for the longest contigs that contain 50% of the total genome length. In the current era of long-read sequencing, a contig N50 over 1 Mb is generally considered good [10].

Troubleshooting Low Contiguity:

- Problem: Assembly appears highly fragmented with low N50 values.

- Solutions:

Completeness

What is measured: Completeness evaluates whether the assembly contains all the expected genomic sequences, particularly conserved coding regions.

Primary Metric:

- BUSCO Score (Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs): Assesses the presence or absence of highly conserved single-copy orthologs specific to the taxonomic group. A BUSCO complete score above 95% is considered good [10].

Troubleshooting Low Completeness:

- Problem: BUSCO scores indicate missing conserved genes.

- Solutions:

Correctness

What is measured: Correctness represents the accuracy of each base pair in the assembly and the structural accuracy of the arrangement. This is the most challenging dimension to assess [10].

Primary Approaches:

- K-mer Analysis: Tools like Merqury compare k-mer presence between assembly and short reads

- Reference Comparison: When available, align to a high-quality reference genome

- Transcript Analysis: Assess frameshifts in coding sequences using RNA-Seq data [10]

Troubleshooting Correctness Issues:

- Problem: High rates of base errors or structural misassemblies.

- Solutions:

- Apply consensus polishing using high-accuracy short reads or HiFi data

- Use Hi-C contact maps to identify and correct misassemblies [11]

- Validate with orthogonal technologies such as Bionano or genetic maps

Table 1: Summary of Core Genome Assembly Metrics

| Dimension | Key Metrics | Target Values | Common Assessment Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Contiguity | Contig N50, Scaffold N50 | >1 Mb for contig N50 | QUAST, AssemblyStats |

| Completeness | BUSCO score, Gene content | >95% complete BUSCOs | BUSCO, CEGMA |

| Correctness | QV score, k-mer completeness | QV >40, k-mer completeness >99% | Merqury, Yak, AssemblyQC |

Advanced Validation Methodologies

K-mer Based Validation with Merqury

Protocol Overview: K-mer analysis provides a reference-free method to assess both completeness and correctness by comparing the k-mers present in the assembly to those in high-quality short-read data from the same individual [10].

Experimental Workflow:

- Generate Illumina short-read data from the same sample used for assembly

- Run Merqury with assembly and short reads as input

- Analyze output spectra-cn plots for k-mer completeness

- Examine QV (Quality Value) scores for base-level accuracy

- Use IGV tracks to visualize potential misassemblies flagged by the tool

Troubleshooting:

- Low k-mer completeness: Indicates missing sequences in the assembly; consider additional sequencing or alternative assemblers

- High k-mer error rate: Suggests base-level inaccuracies; apply additional polishing steps

Hi-C Scaffolding for Structural Validation

Protocol Overview: Hi-C sequencing captures the three-dimensional proximity of genomic regions in the nucleus, providing long-range information for scaffolding and structural validation [11].

Experimental Workflow:

- Perform Hi-C library preparation using crosslinking and proximity ligation

- Sequence Hi-C libraries to appropriate depth (typically 20-50x coverage)

- Process raw reads using Juicer pipeline to create contact maps

- Run 3D-DNA or similar tools for automated scaffolding

- Visualize and manually curate results in Juicebox Assembly Tools [11]

Troubleshooting Common Issues:

- Problem: Juicer deduplication not finishing due to high-coverage regions

- Solution: Create a blacklist of low-complexity and repetitive regions, mask them before mapping, then use unmasked genome for scaffolding [11]

- Problem: Poor Hi-C contact maps with limited long-range contacts

- Solution: Optimize crosslinking conditions and increase sequencing depth

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for comprehensive genome assembly validation, combining multiple data types to assess all three quality dimensions:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Tools and Reagents for Genome Assembly and Validation

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Specific Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio HiFi Reads | Generates long reads with high accuracy (<0.5% error rate) | De novo assembly, variant detection [4] [13] |

| Oxford Nanopore UL Reads | Produces ultra-long reads (>100 kb) | Spanning complex repeats, structural variant detection [4] | |

| Illumina Short Reads | Provides high-accuracy short reads | Polishing, k-mer validation [10] | |

| Assembly Algorithms | hifiasm | Haplotype-resolved assembler for HiFi data | Diploid genome assembly [4] |

| NextDenovo | Progressive error correction with consensus | Consistent, near-complete assemblies [6] | |

| Flye | Graph-based assembler for long reads | Balance of accuracy and contiguity [6] | |

| Validation Tools | BUSCO | Assesses gene content completeness | Evolutionary conservation assessment [10] |

| Merqury | K-mer based quality assessment | Base-level accuracy without reference [10] | |

| Juicer/3D-DNA | Hi-C data processing and scaffolding | Chromosome-scale scaffolding [11] | |

| Specialized Kits | Dovetail Hi-C Kit | Chromatin conformation capture | 3D genome scaffolding [12] |

| SMRTbell Express Kit | PacBio library preparation | HiFi read generation [12] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the minimum recommended sequencing coverage for a high-quality de novo assembly?

- For PacBio HiFi reads: 20-30x coverage is typically sufficient for mammalian-sized genomes

- For Hi-C scaffolding: Additional 20-50x coverage for chromosome-scale assembly

- For polishing/validation: 30-50x Illumina coverage for accurate error correction [13] [12]

Q2: How do we handle correctness assessment when no reference genome exists for our species?

- Use k-mer analysis tools like Merqury that compare assembly to Illumina reads from the same sample

- Perform transcriptome alignment to identify frameshift errors in coding regions

- Consider BAC sequencing or other orthogonal long-range data for validation [10]

Q3: Our assembly has high BUSCO scores but poor k-mer completeness. What does this indicate?

- This suggests your assembly contains most conserved genes but may be missing non-conserved or repetitive regions

- BUSCO assesses only a small fraction of the genome (<1% for conserved genes), while k-mer analysis evaluates the entire sequence space

- Solution: Consider additional sequencing or alternative assemblers that better resolve repetitive content [10]

Q4: What are the key considerations when selecting an assembler for our project?

- Ploidy: Haploid vs. diploid vs. polyploid genomes require different approaches

- Read type: HiFi, Nanopore, or hybrid strategies each have optimal assemblers

- Computational resources: Some tools require significant memory and runtime

- Recent benchmarks show NextDenovo and NECAT perform well for prokaryotes, while hifiasm excels for eukaryotic diploids [6]

Q5: How can we resolve persistent misassemblies in repetitive regions?

- Integrate multiple sequencing technologies (HiFi + Ultra-long + Hi-C)

- Use manual curation tools like Juicebox to examine Hi-C contact maps and correct misjoins

- Apply specialized assemblers like GNNome that use geometric deep learning to navigate complex graph tangles [14]

Future Directions in Assembly Validation

The field of genome assembly is rapidly evolving toward complete telomere-to-telomere (T2T) assemblies for all chromosomes [4]. Emerging approaches include:

- AI-driven assembly: Geometric deep learning frameworks like GNNome that can navigate complex assembly graph tangles [14]

- Standardized visualization: Development of specialized visual grammars for 3D genomics data interpretation [15]

- Pangenome references: Movement beyond single references to pangenomes that capture species diversity [4]

By systematically addressing contiguity, completeness, and correctness through the methodologies outlined in this guide, researchers can produce assembly quality suitable for the most demanding applications in genomics research and therapeutic development.

Troubleshooting Guides

How do I select the right assembler for a genome with high heterozygosity?

Problem: De novo assembly of highly heterozygous genomes results in a fragmented assembly with falsely duplicated regions and an inflated genome size.

Solution: Your choice of assembler should be guided by the measured heterozygosity level of your genome. Use k-mer analysis tools to estimate heterozygosity before assembly.

Table 1: Assembler Recommendations Based on Genome Heterozygosity

| Heterozygosity Level | Recommended Assembler | Assembler Type | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low (< 0.5%) | Redbean [16] | Long-read-only | Stable, high-performance assembly. |

| Moderate (0.5% - 1.0%) | Flye [16] | Long-read-only | Effective for a broad range of complexities. |

| High (> 1.0%) | MaSuRCA [16], Platanus [17] | Hybrid | Uses short reads to correct long-read errors, simplifying complex graph structures. |

Detailed Protocol:

- Estimate Heterozygosity: Use k-mer analysis (e.g., with GenomeScope) on Illumina short-read data to determine the genome's heterozygosity rate [16] [18].

- Assemble: Run the recommended assembler from Table 1 with its default parameters for your genome size.

- Post-Process: All assemblies from heterozygous genomes require purging of haplotigs (redundant allelic contigs). Use tools like Purge Haplotigs or purge_dups after assembly to produce a haploid representation [16] [18].

How can I overcome the challenges of repetitive genomic regions?

Problem: Repetitive sequences cause misassemblies, collapsed regions, and gaps, leading to a loss of genomic context and erroneous gene models.

Solution: Employ long-read sequencing technologies and integrate multiple scaffolding techniques to resolve repeats.

Detailed Protocol:

- Sequence with Long Reads: Use PacBio CLR/HiFi or Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) sequencing. Long reads can span repetitive elements, anchoring them correctly in the assembly [19]. HiFi reads are particularly valuable for their high accuracy [20].

- Use a Redundancy-Based Approach: For genomes with very high heterozygosity (>3%), a specialized workflow can be used. This involves extracting flanking sequences around duplicated single-copy genes and using Hi-C data to cluster and orient these sequences into chromosomes [18].

- Scaffold with Multiple Technologies: Scaffold the initial contig assembly using at least two independent long-range technologies such as Hi-C, optical maps (Bionano), or linked reads (10X Genomics). This integration significantly improves scaffold continuity and validates joins across repetitive regions [19].

My assembled genome size is much larger than expected. What went wrong?

Problem: The final assembled genome size is substantially larger than the flow cytometry or k-mer-based estimate.

Solution: This is a classic symptom of a heterozygous genome where assemblers have failed to merge haplotypes, resulting in two separate contigs for each heterozygous region. You need to "purge" these redundant haplotigs.

Detailed Protocol:

- Identify Haplotigs: Use the tool

purge_dupsorPurge Haplotigsto identify contigs that are alternate haplotypes of the same genomic region. These tools use read depth and sequence similarity to detect redundancies [16] [18]. - Remove Redundancy: Run the purging tool to create a "haploid" representation of the genome by removing the identified haplotigs.

- Validate Genome Size: After purging, the genome size should be much closer to your initial estimate. Re-calculate assembly metrics (e.g., BUSCO completeness) to ensure gene space is retained [18].

How do I accurately determine the ploidy of my sample?

Problem: Uncertainty regarding the ploidy of an organism (e.g., diploid vs. triploid) can lead to incorrect assembly and variant calling parameters.

Solution: Use bioinformatic tools on sequencing data to infer ploidy, especially when flow cytometry is not feasible.

Detailed Protocol:

- Use nQuire: This tool is designed for ploidy estimation from next-generation sequencing data.

- Create a Mapping File: Map your sequencing reads (Illumina or similar) to a reference genome.

- Run nQuire: Execute

nQuireon the mapping file. The tool models the distribution of base frequencies at variable sites using a Gaussian Mixture Model to distinguish between diploid, triploid, and tetraploid samples [21].

- Inspect Allele Frequencies: For a diploid, alleles at heterozygous sites should occur at a ~0.5/0.5 ratio. Triploids will show ratios of ~0.33/0.67, and tetraploids will show a mixture of ~0.25/0.75 and 0.5/0.5 ratios [21].

How can I identify and filter multicopy regions in population genomic data?

Problem: Multicopy regions (e.g., segmental duplications, gene families) collapse during alignment, creating biases in SNP calls and downstream evolutionary analyses.

Solution: Use a method like ParaMask to identify and mask these regions using signatures in your population-level VCF file.

Detailed Protocol:

- Run ParaMask: Provide your VCF file as input to the ParaMask tool.

- Detect Signatures: ParaMask integrates multiple signals:

- Excess Heterozygosity: Collapsed duplicates make an individual appear heterozygous across multiple copies [22].

- Read-Ratio Deviations: Allele ratios may deviate from the expected 0.5 for heterozygotes (e.g., 0.25 or 0.75) [22].

- Excess Sequencing Depth: More reads map to a collapsed multicopy region, increasing local depth [22].

- Filter VCF: Mask or remove SNPs located within the multicopy regions identified by ParaMask to reduce bias in your population genetic analyses [22].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the single most important factor for a high-quality de novo assembly?

The use of long-read sequencing technologies (PacBio or Oxford Nanopore) is the most critical factor. Long reads are essential for maximizing genome quality because they can span repetitive regions and resolve complex areas that fragment short-read assemblies. According to the Vertebrate Genomes Project, contigs from long reads are 30- to 300-fold longer than those from Illumina short reads alone [19].

Why is my genome assembly so fragmented, even with long reads?

High levels of repetitive content are a primary cause of fragmentation. Studies show that contig continuity (NG50) decreases exponentially as genomic repeat content increases [19]. Additionally, high heterozygosity can create complex assembly graphs that are difficult to resolve, leading to fragmentation if not handled by a heterozygous-aware assembler [16] [17].

Can I use only long reads for a complete genome assembly?

While long reads are fundamental for contiguity, a multi-platform approach yields the most complete and accurate assemblies. The VGP pipeline demonstrates that scaffolding long-read contigs with technologies like Hi-C and optical maps can improve continuity by 50% to 150% and help assign sequences to chromosomes [19]. Polishing with accurate short reads can also correct residual base errors in long-read assemblies [16].

What is phasing and why is it important?

Phasing, or haplotype phasing, is the process of determining which genetic variants (e.g., SNPs) lie on the same copy of a chromosome. This is crucial for understanding compound heterozygosity, linking regulatory variants to genes, and accurately representing the biology of diploid and polyploid organisms [20]. Highly accurate long reads (HiFi) are uniquely suited for phasing haplotypes over long ranges [20].

How do I handle a genome with suspected high heterozygosity from the start?

Begin with a heterozygous-aware assembler like Platanus or MaSuRCA [16] [17]. These assemblers are specifically designed to simplify the complex bubble structures in the assembly graph caused by heterozygosity, rather than simply cutting them, which leads to fragmentation. Always follow assembly with a haplotig purging step [16].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Tools and Technologies for Complex Genome Assembly

| Category | Tool/Technology | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Technologies | PacBio HiFi Reads [20] | Generates highly accurate long reads ideal for phasing and base-level accuracy. |

| Oxford Nanopore Long Reads [16] | Provides very long read lengths to span repetitive elements. | |

| Illumina Short Reads [16] | Delivers high base accuracy for polishing long-read assemblies and k-mer analysis. | |

| Assembly Algorithms | Flye, Redbean [16] | Long-read-only assemblers recommended for low to moderate heterozygosity. |

| MaSuRCA [16] | Hybrid assembler that corrects long reads with short reads, good for high heterozygosity. | |

| Platanus [17] | Designed for highly heterozygous genomes, simplifies graph structures during assembly. | |

| Post-Assembly Analysis | purge_dups / Purge Haplotigs [16] [18] | Identifies and removes redundant contigs from heterozygous diploid genomes. |

| nQuire [21] | Estimates ploidy level directly from next-generation sequencing data. | |

| ParaMask [22] | Identifies multicopy genomic regions in population data to reduce analysis bias. | |

| Scaffolding Technologies | Hi-C [19] | Captures chromatin proximity information to scaffold and assign contigs to chromosomes. |

| Bionano Optical Maps [19] | Provides long-range restriction maps to validate and scaffold assemblies. |

The Limitations of Short-Read Sequencing and the Rise of Long-Read Technologies

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics, but researchers face a critical choice between two principal methodologies: short-read and long-read sequencing. Short-read sequencing, which produces fragments of 50-300 base pairs, has dominated the field for over a decade due to its high throughput and cost-effectiveness [23]. However, the limitations of this approach in resolving complex genomic regions have become increasingly apparent, driving the adoption of long-read technologies that can sequence DNA fragments tens to hundreds of kilobases in length [24]. This technical support document examines the specific limitations of short-read sequencing, explores how long-read technologies overcome these barriers, and provides practical guidance for researchers seeking to improve accuracy in de novo genome assembly and variant detection.

The evolution from first-generation sequencing (Sanger and Maxam-Gilbert) to NGS and now to third-generation long-read sequencing represents more than just incremental improvement [25]. Long-read technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) enable single-molecule sequencing without fragmentation, preserving long-range genomic context that is essential for assembling complex regions, detecting structural variations, and phasing haplotypes [24]. For researchers in drug development and clinical diagnostics, understanding these technologies' complementary strengths is crucial for designing experiments that yield biologically meaningful results rather than technical artifacts.

Technical Limitations of Short-Read Sequencing: A Systematic Analysis

Fundamental Technical Constraints

Short-read technologies excel at detecting single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and small indels but face inherent limitations due to their fragmentary nature. The core issue stems from read lengths that are too short to uniquely map across repetitive elements or resolve large structural variations [24]. Approximately 50-69% of the human genome consists of repetitive sequences, including transposable elements, low-complexity regions, and pseudogenes [26]. When short reads are generated from these regions, they cannot be unambiguously mapped to a unique genomic location, creating gaps and misassemblies in the final sequence.

The challenges extend beyond repetitive elements. Regions with extreme GC content (either very high or very low) show significant coverage bias in short-read sequencing, with up to twofold reductions in sequence coverage when GC composition exceeds 45% [26]. This bias affects the ability to discover genetic variation in some of the most functionally important regions of the genome. Additionally, short-read technologies typically require PCR amplification during library preparation, which introduces artifacts and loses information about natural base modifications such as methylation [23].

Impact on Genomic Analyses and Clinical Interpretation

The technical limitations of short-read sequencing have direct consequences for research and clinical applications. Current estimates indicate that only 74.6% of exonic bases in ClinVar and OMIM genes (and 82.1% in ACMG-reportable genes) reside in high-confidence regions accessible to short-read technologies [26]. This means that approximately one-quarter of clinically relevant genes contain regions that are difficult to sequence accurately with short-read technologies. Furthermore, only 990 genes in the entire genome are found completely within high-confidence regions, while 593 of 3,300 ClinVar/OMIM genes have less than 50% of their total exonic base pairs in high-confidence regions [26].

The implications for structural variant detection are even more pronounced. Reads under 300 bases are too short to detect more than 70% of human genome structural variation (>50 bp), with intermediate-size structural variation (<2 kb) especially underrepresented [24]. Entire swaths of the genome (>15%) remain inaccessible to assembly or variant discovery because of their repeat content or atypical GC composition [24]. Ironically, these inaccessible regions include some of the most mutable parts of our genome, both in the germline and soma, meaning that the most dynamic genomic regions are typically the most understudied.

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Short-Read and Long-Read Sequencing Technologies

| Parameter | Short-Read Sequencing | Long-Read Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 50-300 bp | 10 kb to >1 Mb |

| Single-Read Accuracy | >99.9% | 87-98% (Nanopore), >99.9% (PacBio HiFi) |

| Ability to Resolve Repetitive Regions | Limited | Excellent |

| Structural Variant Detection | Limited to ~30% of variants | Comprehensive |

| GC Bias | Significant | Minimal |

| Phasing Capability | Limited statistical phasing | Direct haplotype resolution |

| Epigenetic Detection | Requires special treatment | Native detection possible |

| Typical Applications | SNP detection, gene panels, exome sequencing | De novo assembly, structural variant detection, haplotype phasing |

Long-Read Sequencing Technologies: Principles and Advancements

Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) SMRT Sequencing

PacBio's single-molecule real-time (SMRT) sequencing technology utilizes a topologically circular DNA molecule template called a SMRTbell, comprised of a double-stranded DNA insert with single-stranded hairpin adapters on either end [24]. The DNA insert can range from 1 kb to over 100 kb, enabling long sequencing reads. During sequencing, the SMRTbell is bound by a DNA polymerase and loaded onto a SMRT Cell containing millions of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs) [24]. As the polymerase processes around the circular template, it incorporates fluorescently labeled dNTPs, with the emitted light captured to determine the sequence.

A significant advancement in PacBio technology is the development of HiFi (High Fidelity) reads through circular consensus sequencing. This approach sequences the same molecule multiple times by repeatedly traversing the circular template, generating read accuracies exceeding 99.9% [3]. HiFi sequencing combines long read lengths (typically 15-20 kb) with exceptional accuracy, making it particularly suitable for applications requiring precise variant detection and phasing. Additionally, PacBio sequencing can monitor the kinetics of base incorporation, providing direct detection of DNA base modifications such as methylation without bisulfite treatment [23].

Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) Sequencing

Nanopore sequencing employs a fundamentally different approach based on the detection of electrical current changes as DNA molecules pass through protein nanopores [25]. A constant voltage is applied across a membrane containing an array of nanopores. As negatively charged single-stranded DNA molecules traverse the pores, the current across the pores is disrupted in a manner specific to the DNA's nucleotide sequence [23]. These unique variations in current are interpreted by detectors to determine the nucleotide sequence.

A key advantage of Nanopore sequencing is its ability to generate ultra-long reads, sometimes exceeding hundreds of thousands of bases or even reaching megabase lengths [3]. This technology also offers portability, with instruments like the MinION being suitable for field research and rapid diagnostics. Nanopore can sequence native DNA and RNA directly, including detection of RNA modifications, without the need for amplification [3]. However, Nanopore sequencing typically has higher raw read error rates compared to PacBio HiFi, though recent chemistry improvements (R10.4.1) have achieved modal accuracy of Q20 [27].

Diagram 1: Long-Read Sequencing Workflows - This diagram illustrates the fundamental processes for both PacBio SMRT sequencing (yellow) and Nanopore sequencing (green), highlighting key steps from library preparation to data generation.

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: When should I choose long-read sequencing over short-read for my de novo assembly project?

Long-read sequencing is essential when assembling genomes with high repeat content, complex structural variations, or when haplotype-resolved assembly is required. Short-read technologies struggle with repetitive sequences because reads are too short to uniquely span repetitive elements, leading to gaps and misassemblies [24]. Long reads can traverse entire repetitive regions, enabling more complete and contiguous assemblies. For example, the Telomere-to-Telomere (T2T) consortium completely assembled human chromosomes using long-read technologies, resolving previously inaccessible regions including centromeres and telomeres [4]. If your research involves genomic regions with segmental duplications, tandem repeats, or complex structural variations, long-read sequencing should be your primary approach.

FAQ 2: How does read accuracy compare between PacBio HiFi and Nanopore sequencing?

PacBio HiFi reads consistently achieve accuracy rates exceeding 99.9% (Q30), comparable to Sanger sequencing and high-quality short reads [3]. This high accuracy results from the circular consensus sequencing approach that sequences the same molecule multiple times. In contrast, Oxford Nanopore Technologies typically produces raw reads with lower accuracy, approximately Q20 (99%) for their latest chemistry, though this can be improved through deeper coverage and computational polishing [27] [3]. However, accuracy metrics don't tell the whole story - Nanopore's strength lies in producing ultra-long reads (sometimes >100 kb) that can span massive repetitive regions, and its capacity for direct RNA sequencing and detection of base modifications.

FAQ 3: What are the key considerations for sample preparation in long-read sequencing?

Successful long-read sequencing requires high molecular weight DNA, as fragment sizes directly impact read lengths. For optimal results, DNA should be extracted using methods that minimize shearing, such as agarose plug extraction or specific commercial kits designed for long-read sequencing [25]. DNA quality assessment should include not just spectrophotometric measurements but also fragment size analysis through pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or Fragment Analyzer systems. For PacBio sequencing, the recommended DNA input is 5-10 μg with fragment sizes >20 kb, while Nanopore sequencing can work with lower inputs but still benefits from longer fragments [3]. Proper sample handling is critical - avoid vortexing, repetitive freeze-thaw cycles, and use wide-bore tips to prevent mechanical shearing.

FAQ 4: How can I improve the accuracy of my long-read assemblies?

Several strategies can enhance assembly accuracy:

- Combine sequencing technologies: Hybrid approaches using both long and short reads leverage their complementary strengths. Long reads provide scaffolding power while short reads offer base-level accuracy [27].

- Implement robust polishing pipelines: Tools such as Racon, Medaka, and Pilon can correct errors in draft assemblies using sequencing reads [28].

- Utilize specialized assemblers: Choose assemblers designed for your data type - for example, hifiasm for PacBio HiFi data, Flye for Oxford Nanopore data, or Canu for more generic long-read assembly [29] [28].

- Incorporate additional data types: Hi-C data can scaffold assemblies to chromosome level, while optical mapping can validate large-scale assembly structure [24].

- Apply assembly evaluation tools: Use Inspector, Merqury, or QUAST to identify and correct assembly errors, especially structural errors that are common in complex regions [29].

Long-read data analysis demands significant computational resources, particularly for Oxford Nanopore data. A typical human genome sequenced with Nanopore at 30× coverage can generate ~1.3 terabytes of raw data (FAST5/POD5 format) [3]. Base calling requires powerful GPU servers and can take days per genome. In comparison, PacBio HiFi data produces smaller files (~30-60 GB per genome) with base calling performed on-instrument [3]. For assembly, memory requirements can exceed 500 GB of RAM for vertebrate genomes, with compute times ranging from days to weeks depending on the genome size and assembler. Always verify the specific computational requirements for your chosen analysis tools and plan infrastructure accordingly.

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Genome Assembly

Hybrid Sequencing and Assembly Protocol

Combining long-read and short-read sequencing data leverages their complementary strengths to produce more accurate and complete genome assemblies. This protocol outlines an optimized workflow for hybrid genome assembly:

Library Preparation and Sequencing:

- Generate long-read data (PacBio HiFi or ONT) at minimum 20× coverage for scaffolding

- Generate short-read Illumina data at minimum 30× coverage for polishing

- For PacBio: Use the SMRTbell express template prep kit with size selection >20 kb

- For ONT: Use ligation sequencing kit with LSK-114 or newer, aiming for N50 >20 kb

- For Illumina: Use PCR-free library prep to minimize bias, 2×150 bp reads

Initial Assembly with Long Reads:

- Assess read quality: Use NanoPlot for ONT data, SMRT Link for PacBio data

- Perform initial assembly with a long-read assembler:

- For PacBio HiFi: Use hifiasm with parameters

-l0for accurate haplotig generation - For ONT: Use Flye with parameters

--nano-hqfor high-quality reads or--nano-rawfor standard reads

- For PacBio HiFi: Use hifiasm with parameters

- Evaluate initial assembly: Use Inspector for comprehensive error profiling [29]

Polish Assembly with Short Reads:

- Map short reads to assembly using BWA-MEM or Minimap2

- Perform two rounds of Racon polishing followed by one round of Pilon polishing [28]

- Validate polishing improvements using Merqury with short-read k-mer spectra

Assembly Evaluation and Validation:

- Run Inspector to identify remaining structural errors and small-scale errors [29]

- Assess completeness with BUSCO against appropriate lineage dataset

- For maximum accuracy, consider manual curation of identified problematic regions

This hybrid approach has been shown to produce assemblies that outperform single-technology methods, with one study reporting that a shallow hybrid approach (15× ONT + 15× Illumina) can match the variant detection accuracy of deep single-technology sequencing [27].

Assembly Evaluation and Error Correction Protocol

Comprehensive evaluation is essential for identifying and resolving assembly errors. This protocol uses Inspector, a reference-free evaluator that reports error types and locations:

Data Preparation and Alignment:

- Input: Assembly contigs and long reads used for assembly

- Align reads to contigs using Minimap2 with parameters

-x map-ontfor ONT or-x map-pbfor PacBio - Sort and index the resulting BAM file using SAMtools

Assembly Error Detection:

- Run Inspector with command:

inspector.py -c contigs.fa -b aligned.bam -o output_dir - Inspector identifies four types of structural errors (≥50 bp): expansion, collapse, haplotype switch, and inversion [29]

- Inspector also detects three types of small-scale errors (<50 bp): base substitution, small collapse, and small expansion

- Run Inspector with command:

Error Correction Implementation:

- For each identified error region, extract the corresponding reads and contig sequence

- Generate consensus sequence from reads using Medaka for ONT or Racon for PacBio data

- Replace erroneous regions in the assembly with corrected consensus sequences

- Validate corrections by realigning reads to the corrected assembly

Quality Assessment:

- Compare pre- and post-correction assembly metrics using QUAST-LG

- Verify error resolution by checking that previously identified error regions now show proper read support

- Assess overall assembly quality using Merqury quality value (QV) score

In benchmark tests, Inspector correctly identified over 95% of simulated structural errors with both PacBio CLR and HiFi data, with precision over 98% in both haploid and diploid simulations [29]. This makes it particularly valuable for evaluating assemblies where a high-quality reference genome is unavailable.

Diagram 2: Hybrid Assembly and Evaluation Workflow - This diagram illustrates the integrated process of combining long-read and short-read data to produce validated, high-quality genome assemblies, highlighting the iterative nature of assembly improvement.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Long-Read Sequencing and Assembly

| Category | Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction | Nanobind CBB Kit | High molecular weight DNA extraction | Preserves long fragments >50 kb; critical for long-read sequencing |

| Agarose Plugs | DNA isolation with minimal shearing | Gold standard for ultra-long reads >100 kb | |

| Library Prep | SMRTbell Express Prep Kit | PacBio library construction | Optimal for 5-20 kb inserts; requires 3-5 μg input DNA |

| Ligation Sequencing Kit (LSK) | ONT library preparation | Compatible with native DNA; enables methylation detection | |

| Sequencing | SMRT Cell 8M | PacBio sequencing reactor | Contains 8 million ZMWs; yields 60-120 Gb on Revio system |

| PromethION Flow Cell | ONT high-throughput sequencing | 3000 pores; yields 50-100 Gb per flow cell | |

| Assembly Software | hifiasm | Haplotype-resolved assembler | Optimized for PacBio HiFi data; preserves haplotype information |

| Flye | Long-read de novo assembler | Works well with both PacBio and ONT data; handles repetitive regions | |

| Canu | Adaptive assembler | Automatically adjusts parameters based on data characteristics | |

| Evaluation Tools | Inspector | Assembly error identification | Detects structural and small-scale errors without reference [29] |

| Merqury | k-mer based quality assessment | Evaluates assembly base accuracy using read k-mer spectra | |

| QUAST-LG | Assembly metrics calculation | Comprehensive quality assessment tool for large genomes |

The limitations of short-read sequencing have become increasingly apparent as researchers tackle more complex genomic regions and seek to understand the full spectrum of genetic variation. Long-read technologies have emerged as essential tools for overcoming these limitations, enabling complete telomere-to-telomere assemblies, comprehensive structural variant detection, and haplotype-resolved sequencing [4]. While short-read sequencing remains valuable for applications requiring high base-level accuracy at low cost for simple genomic regions, long-read technologies provide the necessary long-range context for resolving complex genomic architectures.

The future of genomics lies not in choosing one technology over another, but in strategically combining their complementary strengths. Hybrid approaches that integrate long-read scaffolding with short-read polishing can achieve accuracy and completeness that neither technology can deliver alone [27] [28]. As long-read technologies continue to improve in accuracy, throughput, and cost-effectiveness, they are poised to become the default choice for de novo genome assembly and comprehensive variant detection. Researchers and drug development professionals who master these technologies and their integrated applications will be best positioned to unlock the full potential of genomic medicine and advance our understanding of genetic complexity in health and disease.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What makes centromeres and rDNA so difficult to assemble accurately? These regions are composed of long, highly repetitive DNA sequences. Centromeres often consist of tandem repeats of alpha-satellite DNA organized into higher-order repeat (HOR) arrays [30] [31], while ribosomal DNA (rDNA) consists of hundreds to thousands of tandemly repeated copies of a single unit [32]. Standard short-read sequencing technologies produce reads that are too short to uniquely map across these repeats, leading to gaps, misassemblies, and collapsed regions in the genome assembly.

Q2: Why are polyploid genomes particularly challenging for assembly? Polyploid genomes contain multiple complete sets of chromosomes (subgenomes), often from different progenitor species. These subgenomes can be highly similar, making it difficult to correctly assign sequences to their correct origin during assembly. This can lead to a chimeric assembly where homologous chromosomes are incorrectly merged [33] [34]. For example, sugarcane cultivars are complex hybrids with a ploidy of approximately 12x and about 114 chromosomes, resulting from interspecific hybridization and backcrossing [34].

Q3: What are the functional consequences of assembly errors in these regions? Errors can lead to an incomplete or incorrect understanding of genome biology. In centromeres, errors can obscure the true kinetochore position, which has been shown to differ by more than 500 kb between individuals [31]. In polyploids, collapsed assemblies prevent researchers from studying the distinct evolutionary contributions and interactions of each subgenome, which is crucial for traits like disease resistance in crops [35] [34]. For rDNA, incorrect copy number can impact the study of cellular aging and disease [32].

Q4: What modern technologies and methods are helping to overcome these hurdles?

- Long-Read Sequencing: Technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore generate reads tens of thousands of bases long, which can span entire repetitive units and provide the continuity needed to resolve complex regions [31] [34].

- Advanced Assembly Polishing: Tools like DeepPolisher use deep learning on transformer architectures to correct base-level errors in genome assemblies, reducing insertion/deletion errors by over 70% and improving overall assembly quality (Q-score) [36].

- Multi-Platform Scaffolding: Combining long-read sequencing with Hi-C, optical mapping, and genetic maps allows researchers to anchor assemblies into chromosome-scale scaffolds, even in highly repetitive genomes like sugarcane [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Challenge 1: Assembling Highly Repetitive Centromeric Regions

Problem: The assembly of centromeres is fragmented or completely absent, preventing analysis of their structure and variation.

Solution: Adopt a multi-faceted approach that leverages ultra-long reads and specialized algorithms.

- Generate Ultra-Long Reads: Sequence the genome using Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT) to produce reads >100 kb. These long reads are essential for spanning large, identical HOR arrays [31].

- Supplement with HiFi Reads: Generate high-fidelity (HiFi) PacBio sequencing data. These reads are shorter than ONT ultra-long reads but have very high per-base accuracy (>99.9%), which is crucial for resolving subtle sequence variations within repeats [31].

- Use Unique K-mer Barcoding: Employ methods that use singly unique nucleotide k-mers (SUNKs) to "barcode" contigs derived from HiFi data. Ultra-long ONT reads that share these barcodes can then be used to bridge and connect contigs across the repetitive centromeric space [31].

- Validate with Independent Data: Use methods like GAVISUNK to compare SUNKs in the assembly to those in raw ONT data to confirm assembly integrity. Additionally, perform CENH3 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP-seq) to experimentally delineate the functional centromere and validate its position in the assembly [31] [35].

Table 1: Key Metrics for Centromere Assembly Quality Control

| Metric | Description | Target Value/Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Contiguity | Size of the largest contiguous sequence (contig) spanning the centromere. | Megabase-scale contigs without gaps [31]. |

| Sequence Identity | Comparison of aligned centromeric sequences between two assembled haplotypes. | ~98.6% for alignable α-satellite HOR arrays; significant portions may be unalignable due to novel HORs [31]. |

| CENH3 Enrichment | Co-localization of the assembly with experimental CENH3-ChIP data. | A single, defined region of enrichment matching known kinetochore position [35]. |

Challenge 2: Resolving Complex Polyploid Genome Architectures

Problem: The assembly is a chimeric "mosaic" where homologous chromosomes from different subgenomes are incorrectly merged, obscuring true genetic variation.

Solution: Implement a assembly strategy designed for polyploids that separates highly similar haplotypes.

- Opt for a "Partial-Inbred" Assembly Structure: Create a primary assembly that represents all unique DNA sequences and an "alternate" assembly that contains nearly identical, additional haplotypes. This avoids collapsing highly similar but distinct sequences from different subgenomes [34].

- Leverage Hi-C for Phasing: Use Hi-C proximity ligation data to cluster and partition sequencing reads by their chromosome of origin. This helps to disentangle the contributions of different subgenomes based on the 3D conformation of chromatin in the nucleus [37].

- Integrate Multiple Data Types for Scaffolding: Use a custom pipeline that combines genetic linkage maps, synteny with related species, and optical mapping to correctly order and orient contigs into chromosomes. This is especially important in polyploids where short, unique sequence anchors are rare [34].

- Annotate Progenitor Origins: For hybrid polyploids (allopolyploids), identify species-specific repetitive elements or k-mers. Use these to assign chromosomal segments in the assembly to their correct wild or domesticated progenitor genome [34].

Table 2: Progenitor Genome Composition in a Sugarcane Polyploid Assembly [34]

| Progenitor Species | Genome Size Contribution (Gb) | Percentage of Primary Assembly | Key Traits |

|---|---|---|---|

| Saccharum officinarum (Domesticated) | 3.66 Gb | 73% | High sugar yield |

| Saccharum spontaneum (Wild) | 1.37 Gb | 27% | Disease resistance, environmental adaptation |

Challenge 3: Achieving Base-Level Accuracy in Final Assemblies

Problem: Even with long-read technologies, the final genome assembly contains small but critical base-level errors (indels and SNPs) that can disrupt gene annotation.

Solution: Incorporate a dedicated assembly polishing step using modern, high-fidelity tools.

- Apply Deep Learning-Based Polishing: Use a tool like DeepPolisher, which employs a transformer model trained on a highly accurate reference genome. It takes the sequenced bases, their quality scores, and mapping uniqueness to predict and correct errors [36].

- Measure Improvement with Q-scores: Quantify assembly accuracy using the Phred-scaled Q-score. A Q-score of 30 indicates 99.9% accuracy (1 error per 1,000 bases), while Q60 indicates 99.9999% accuracy (1 error per 1 million bases). DeepPolisher has been shown to improve assembly Q-scores from ~66.7 to ~70.1 [36].

- Focus on Indel Reduction: Prioritize tools that specifically target insertion and deletion errors, as these are the most common and damaging type of error in long-read assemblies, often causing frameshifts in coding sequences [36].

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Chromatin Immunoprecipitation for Functional Centromere Delineation (CENH3-ChIP-seq)

Purpose: To experimentally identify the genomic regions that form the functional kinetochore, which can then be used to validate centromere assemblies [35].

Methodology:

- Crosslink Chromatin: Treat plant or animal tissue with formaldehyde to crosslink proteins to DNA.

- Isolate Nuclei and Fragment Chromatin: Lyse cells and isolate nuclei. Sonicate the chromatin to shear DNA into fragments of 200–500 bp.

- Immunoprecipitation: Incubate the fragmented chromatin with an antibody specific to the centromeric histone variant CENH3 (or CENP-A in humans). Precipitate the antibody-protein-DNA complexes.

- Reverse Crosslinks and Purify DNA: Heat the sample to reverse the formaldehyde crosslinks and purify the enriched DNA fragments.

- Library Preparation and Sequencing: Prepare a sequencing library from the purified DNA and sequence it using an Illumina platform.

- Data Analysis: Map the sequenced reads to your genome assembly. The regions with significant enrichment of CENH3 ChIP-seq reads compared to an input (control) sample define the functional centromeres.

Protocol 2: A Multi-Platform Scaffolding Pipeline for Complex Genomes

Purpose: To achieve a chromosome-scale assembly for a highly complex, repetitive, and polyploid genome where standard scaffolding fails [34].

Methodology:

- Generate Initial Contigs: Produce a highly accurate backbone assembly from PacBio HiFi reads using an assembler like hifiasm [31] [34].

- Incorporate Long-Range Data:

- Bionano Optical Mapping: Generate a physical map that provides a unique "barcode" pattern of large DNA molecules, helping to confirm contig order and orientation over long distances.

- Hi-C Sequencing: Use Hi-C data to cluster contigs into chromosome groups and order them based on the proximity ligation signals.

- Integrate with Genetic Maps: If available, use a pre-existing genetic linkage map to further validate and correct the ordering of scaffolds.

- Leverage Synteny: Use the chromosome structure of a closely related, well-assembled species as a guide for scaffolding.

- Resolve Haplotypes: For polyploid genomes, use the integrated data in a custom pipeline to separate primary and alternate haplotypes, preventing the creation of a chimeric reference [34].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Tools and Reagents for Tackling Assembly Challenges

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| PacBio HiFi Reads | Generates long reads (10-20 kb) with very high accuracy (>99.9%). | Resolving sequence variation within repetitive centromeric HORs and between subgenomes in polyploids [31] [34]. |

| Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long Reads | Generates reads >100 kb, often exceeding several hundred kilobases. | Spanning entire repetitive arrays in centromeres and rDNA loci to connect unique flanking sequences [31]. |

| CENH3 Antibody | Specifically binds the centromere-specific histone variant for ChIP experiments. | Mapping the exact location of functional kinetochores to validate assembled centromeric regions [35]. |

| Hi-C Kit (e.g., Arima) | Captures the 3D architecture of chromatin in the nucleus via proximity ligation. | Phasing polyploid subgenomes and scaffolding contigs into chromosome-scale assemblies [34] [37]. |

| DeepPolisher Software | A deep learning tool that corrects base-level errors in a draft genome assembly. | Final "polishing" of an assembly to reduce indel and SNP errors before gene annotation and analysis [36]. |

| Bionano Saphyr System | Creates genome-wide optical maps of long DNA molecules, revealing a unique pattern of enzyme cut sites. | Validating overall assembly structure, detecting large-scale misassemblies, and scaffolding over repetitive regions [34]. |

Workflow Visualizations

Advanced Genome Assembly Workflow

Deep Learning Assembly Polishing

Advanced Methods for Precision Assembly: From Technology Choice to Algorithm Selection

For researchers embarking on de novo genome assembly, the choice of sequencing technology is paramount to achieving a contiguous and accurate reconstruction of a species' genome. Long-read sequencing technologies from PacBio and Oxford Nanopore have revolutionized this field by spanning repetitive regions and resolving complex structural variations that were previously intractable with short-read technologies. This technical support center focuses on the critical comparison between PacBio's High Fidelity (HiFi) reads and Oxford Nanopore's Ultra-Long (UL) reads, providing troubleshooting guides, FAQs, and detailed protocols to help you optimize these technologies for the highest fidelity outcomes in your genome assembly projects.

Technology Comparison: Core Specifications and Performance

Sequencing Principle and Workflow

Understanding the fundamental technology principles is crucial for troubleshooting and experimental design.

PacBio HiFi Sequencing utilizes Single Molecule, Real-Time (SMRT) sequencing. DNA polymerase enzymes, immobilized at the bottom of zero-mode waveguides (ZMWs), synthesize a complementary DNA strand. The incorporation of fluorescently-labeled nucleotides generates a light pulse in real-time, which is detected to determine the sequence [3] [38]. HiFi reads are generated through a circular consensus sequencing (CCS) mode. A single DNA molecule is sequenced repeatedly as the polymerase travels around a circularized template. This multi-pass process corrects random errors, producing highly accurate long reads [39] [38].

Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long Sequencing is based on the transit of a DNA molecule through a protein nanopore embedded in an electrically resistant membrane. An applied voltage creates an ionic current, and as nucleotides pass through the pore, they cause characteristic disruptions in this current. These signal changes are decoded in real-time to determine the DNA sequence [3] [38]. The key to Ultra-Long reads is a specialized sample preparation protocol designed to preserve the integrity of very high molecular weight DNA, allowing for the sequencing of contiguous molecules that can be megabases in length.

Performance Metrics forDe NovoAssembly

The following table summarizes the critical performance metrics that impact assembly quality.

Table 1: Performance Metric Comparison for Genome Assembly

| Metric | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore UL |

|---|---|---|

| Read Length | 15-20+ kb [3] | 20 kb to >1 Mb (Ultra-Long) [3] [38] |

| Raw Read Accuracy | >99.9% (Q30+) [3] [39] | ~93.8-98% (Q10-Q20), varies with chemistry & basecaller [3] [38] |

| Consensus Accuracy | Inherent from single-molecule CCS | >99.996% (Q44) achievable with high coverage and polishing [38] |

| Typical Yield per Run | 60-120 Gb (Revio) [3] | 50-100 Gb (PromethION) to 1.9 Tb [3] [38] |

| DNA Modification Detection | Direct detection of 5mC, 6mA without special treatment [3] [39] | Direct detection of 5mC, 5hmC, and others [3] |

| Best Suited For | Highly accurate, finished-grade assemblies; variant phasing; SV detection [3] | Extremely contiguous assemblies; resolving complex repeats; large SV detection [38] |

Computational and Cost Considerations

Table 2: Computational Resource and Cost Analysis

| Consideration | PacBio HiFi | Oxford Nanopore UL |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Data File Size | ~30-60 GB (BAM format) [3] | ~1300 GB (FAST5/POD5 format) [3] |

| Monthly Storage Cost (Example) | ~$0.69 - $1.38 [3] | ~$30.00 [3] |

| Basecalling | On-instrument, included [3] | Off-instrument, requires powerful GPU server [3] |

| Coverage Requirement | Lower (~15-20x) due to high accuracy [3] | Higher (~30-50x+) to enable accurate consensus [38] |

| Common Assembly Pipelines | Hifiasm, HiCanu [40] | Canu, Flye, Shasta, NECAT [40] |

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guide

Technology Selection

Q1: My primary goal is a highly accurate, base-perfect genome assembly for publication. Which technology should I prioritize? A: PacBio HiFi is the superior choice. Its inherent Q30 accuracy simplifies the assembly process, reduces the need for computationally intensive polishing steps, and provides high confidence in the final base calls, especially for identifying small variants like SNPs and indels [3] [39]. This makes it ideal for building reference-quality genomes.

Q2: I am assembling a large, repetitive genome (e.g., a conifer or maize) and need to span massive repeats. What is the best option? A: Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long reads are uniquely capable here. Reads that are hundreds of kilobases to megabases long can span even the most extensive repetitive regions, preventing assembly fragmentation and providing a more complete picture of the genome's structure [38].

Q3: Can I combine both technologies in a single project? A: Yes, this is a powerful hybrid strategy. You can use Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long reads to create a highly contiguous, long-range scaffold of the genome. Then, use PacBio HiFi reads to "polish" this scaffold with single-molecule accuracy, correcting base-level errors and confidently calling variants in the final sequence [40]. This approach leverages the strengths of both platforms.

Experimental Protocol Troubleshooting

Q4: I am not achieving the expected Ultra-Long read lengths with Oxford Nanopore. What could be the issue?

- Problem: DNA degradation during extraction or handling.

- Solution: Use fresh, high-quality tissue and gentle extraction protocols (e.g., CTAB or magnetic bead-based kits). Avoid vortexing and excessive pipetting. Check DNA integrity using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis.

- Problem: Inappropriate DNA shearing during library preparation.

- Solution: For Ultra-Long libraries, follow the Ligation Sequencing Kit protocol without fragmentation steps. Use wide-bore tips for all liquid handling.

Q5: My PacBio HiFi library yield is low, impacting my projected coverage. How can I improve this?

- Problem: Inefficient SMRTbell library ligation.

- Solution: Accurately quantify input DNA using a fluorescence-based assay (e.g., Qubit). Ensure the DNA is high molecular weight. Precisely follow the recommended enzyme-to-template ratios and incubation times in the SMRTbell prep kit protocol [41].

- Problem: Damage to the SMRTbell template.

- Solution: Minimize freeze-thaw cycles of the library. Store libraries at recommended temperatures and handle gently.

Q6: My computational polishing step for Nanopore data is not improving consensus accuracy. What should I check?

- Problem: Insufficient sequencing coverage.

- Solution: Ensure you have achieved a minimum of 40x coverage, and preferably higher (60x), to provide a solid foundation for polishing algorithms to work effectively [38].

- Problem: Using an outdated or inappropriate polishing tool.

- Solution: Use modern, dedicated polishers like Medaka (from ONT) or NextPolish. Ensure the polisher is compatible with your basecalling version and the specific flow cell chemistry used.

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Optimized High Molecular Weight (HMW) DNA Extraction for Ultra-Long Sequencing

Function: To obtain ultra-long, intact DNA molecules crucial for both PacBio HiFi and Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long sequencing. This is the most critical step for achieving long read lengths.

Materials:

- Fresh tissue or cell culture

- Liquid Nitrogen and mortar & pestle

- HMW DNA Extraction Kit (e.g., Nanobind or CTAB-based)

- Proteinase K

- RNAse A

- Wide-bore pipette tips (for handling)

- Pulsed-Field Gel Electrophoresis (PFGE) system for quality control

Method:

- Cell Lysis: Flash-freeze tissue in liquid nitrogen and grind to a fine powder. For cells, use a gentle lysis buffer with Proteinase K. Avoid mechanical disruption.

- Nucleic Acid Isolation: Follow kit protocol for HMW DNA. Prefer methods that use magnetic beads or gentle organic extraction to minimize shear.

- Purification: Treat with RNAse A to remove RNA. Perform buffer exchange into a low-EDTA or EDTA-free elution buffer (e.g., TE), as EDTA can interfere with sequencing chemistry.

- Quality Control:

- Quantity: Use Qubit fluorometer.

- Size and Integrity: Analyze using PFGE or FEMTO Pulse system. A successful extraction should show a dominant band >50 kbp, with a significant fraction >100 kbp for Ultra-Long workflows.

Protocol 2: De Novo Genome Assembly Workflow Using PacBio HiFi Reads

Function: To reconstruct a contiguous and highly accurate genome sequence from PacBio HiFi reads.

Materials:

- PacBio HiFi sequencing data (FASTQ format)

- High-performance computing (HPC) cluster

- Genome assembler (e.g., Hifiasm or HiCanu)

- Quality assessment tools (e.g., QUAST, BUSCO)

Method:

- Data QC: Run

pycoQCor similar to verify read length distribution and quality scores (should be Q30+). - Genome Assembly: Hifiasm performs a haplotype-aware assembly, which is crucial for resolving heterozygous regions in diploid genomes [40].

- Output Primary Contigs: Extract the primary assembly contigs from the

*.p_ctg.gfaoutput file. - Assembly QC:

- Contiguity: Calculate N50/L50 statistics using QUAST.

- Completeness: Assess the percentage of conserved single-copy orthologs found using BUSCO.

Protocol 3: De Novo Genome Assembly Workflow Using Oxford Nanopore Ultra-Long Reads

Function: To generate a highly contiguous genome assembly using Ultra-Long reads, followed by polishing to improve base-level accuracy.

Materials:

- Oxford Nanopore UL sequencing data (POD5/FAST5 and FASTQ)

- GPU server for basecalling (optional but recommended)

- Assembly software (e.g., Flye or Canu)

- Polishing software (e.g., Medaka)

Method:

- Basecalling (if needed): Use the latest basecaller (e.g.,

dorado) with a super-accuracy model to convert raw signal to sequence. - Read Filtering: Filter reads by length (e.g., keep >50 kbp) using

NanoFilt. - Genome Assembly:

- Polishing: Use the same UL reads or complementary HiFi reads to correct errors.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for High-Fidelity Sequencing

| Item | Function | Technology |

|---|---|---|

| Magnetic Bead-based HMW DNA Kit | Gentle isolation of ultra-long DNA fragments | Both (Critical for ONT UL) |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | Prepares DNA into SMRTbell libraries for PacBio sequencing [41] | PacBio HiFi |

| Ligation Sequencing Kit (SQK-LSK114) | Prepares Ultra-Long DNA libraries for nanopore sequencing | Oxford Nanopore UL |

| Short Read Eliminator (SRE) Kit | Enzymatically removes short DNA fragments to enrich for long molecules [41] | Both |

| NEB Next Ultra II End Repair/dA-Tailing Module | Prepares DNA ends for adapter ligation | Both |

| AMPure PB / ProNex Beads | Size selection and clean-up of DNA libraries | Both |

| Dorado Basecaller | Converts raw current signal to nucleotide sequence (requires GPU) | Oxford Nanopore |

| SMRT Link Software | Instrument control, sequencing, and primary data analysis (HiFi generation) [41] | PacBio HiFi |

Hybrid sequencing represents a powerful methodological paradigm in genomics, combining the high accuracy of short-read data with the long-range continuity of long-read technologies. This approach is particularly transformative for de novo genome assembly, where it enables the generation of highly contiguous and accurate reconstructions of complex genomes. By integrating data from platforms such as Illumina (short-read) with Oxford Nanopore (ONT) or Pacific Biosciences (PacBio) long-reads, researchers can overcome the limitations inherent to using either technology alone. This guide provides troubleshooting and experimental protocols to optimize hybrid sequencing for improving accuracy in your de novo assembly research.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the primary advantage of using a hybrid sequencing approach over long-read-only assembly?

Hybrid sequencing synergistically combines the high per-base accuracy of short-read sequencing (often ≥99.9%) with the long-range phasing capability of long-read sequencing (read lengths of 5,000–100,000+ bp). While long-read technologies are excellent for resolving repetitive sequences and structural variants, they can have higher raw error rates (85–98% accuracy). The short-read data is used to correct these errors, resulting in a highly accurate and contiguous final assembly without the excessive cost of achieving ultra-high coverage with long-reads alone [42].

2. My hybrid assembly is highly fragmented. What are the main culprits?

High fragmentation often stems from:

- Insufficient Long-Read Coverage: While hybrid methods reduce the required long-read coverage, it must still be sufficient to span repetitive regions. A common benchmark is to aim for a minimum of 20-25X long-read coverage to ensure continuity [42] [43].

- Suboptimal DNA Quality: The success of long-read sequencing is critically dependent on high-molecular-weight (HMW), high-quality DNA input. Degraded or sheared DNA will prevent the generation of long reads necessary to scaffold fragmented regions [44].

- Choice of Assembler: Different assemblers are optimized for different data types and genome characteristics. Benchmarking has shown that assemblers like Flye and MaSuRCA, which are designed to leverage both data types, often produce superior results compared to those designed for a single data type [45] [46] [43].

3. How do I choose the right assembler for my hybrid sequencing data?

The choice depends on your priorities: continuity, accuracy, or computational efficiency. Recent benchmarks on human genome data indicate that Flye followed by polishing with Racon (using long-reads) and Pilon (using short-reads) provides an excellent balance of accuracy and contiguity [43]. For prokaryotic genomes, Unicycler is highly regarded for its ability to produce circularized assemblies, while MaSuRCA creates "super-reads" from short-reads before scaffolding with long-reads, which can be highly accurate [45] [46]. See the table in the Troubleshooting Guide for a detailed comparison.

4. What are the critical quality control steps for input DNA?

- Purity: Check absorbance ratios (A260/230 and A260/280) using a spectrophotometer. Optimal A260/280 is ~1.8 and A260/230 should be >1.8 to rule out contaminants like phenol or salts that inhibit enzymes [44].

- Integrity: Always use fluorometric quantification (e.g., Qubit) for accurate concentration measurement, as spectrophotometry can overestimate yield. Assess DNA integrity using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis or fragment analyzers to confirm the presence of HMW DNA [43] [44].

Troubleshooting Guide

Common Hybrid Assembly Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |