The Complete RNA-seq Data Quality Control Checklist: From Raw Reads to Clinically Validated Results

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an end-to-end framework for RNA-seq data quality control.

The Complete RNA-seq Data Quality Control Checklist: From Raw Reads to Clinically Validated Results

Abstract

This comprehensive guide provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with an end-to-end framework for RNA-seq data quality control. Covering foundational concepts, methodological applications, advanced troubleshooting, and validation strategies, the article delivers a practical checklist to ensure data integrity from sequencing run evaluation to biological interpretation. By addressing common pitfalls and offering optimization techniques, it empowers scientists to generate reliable, reproducible transcriptomic data suitable for biomarker discovery and clinical translation.

Understanding RNA-seq QC Fundamentals: Why Quality Control is Non-Negotiable

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized transcriptomics by enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with high sensitivity and accuracy [1]. As the technology has become more accessible, the demand for robust and standardized data analysis workflows has grown significantly. In both research and clinical settings, the analysis of RNA-seq data is commonly structured into three distinct stages: primary, secondary, and tertiary analysis [2]. This structured approach ensures that large, complex datasets are processed systematically, with appropriate quality control at each step, to yield reliable biological insights. Understanding these pillars is fundamental to producing high-quality, reproducible results in fields ranging from basic molecular biology to drug development and precision medicine.

Primary Analysis: From Raw Signals to Sequence Reads

Primary analysis encompasses the initial processing steps that convert raw sequencing output into usable sequence data. This foundation is critical, as errors introduced at this stage propagate through all subsequent analyses [2].

Base Calling and Demultiplexing

During sequencing, instruments generate raw data files in binary base call (BCL) format. These files are converted into FASTQ files, which are text-based files containing the sequence reads and their corresponding quality scores [2]. A key step in this conversion is demultiplexing, where sequences are sorted back to their sample of origin based on their unique index sequences (barcodes). This allows multiple samples to be sequenced simultaneously in a single run. Tools such as bcl2fastq (Illumina) or iDemux (Lexogen) perform this demultiplexing and can correct minor errors in index sequences, maximizing data recovery [2].

Sequencing Run Quality Control

Before proceeding with analysis, the quality of the sequencing run itself must be evaluated. Key metrics include:

- Q-score/Q30: Measures base-calling accuracy. A Q30 score indicates a 99.9% base call accuracy [2].

- Cluster Density: The number of clusters per mm² on the flow cell, which should be within the instrument's optimal specifications.

- Reads Passing Filter (PF): The percentage of reads that pass the instrument's internal quality filters.

These metrics should be reviewed using tools like Illumina's Sequencing Analysis Viewer to ensure the run performed within expected parameters [2].

UMI Extraction and Read Trimming

If Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) were incorporated during library preparation to account for PCR amplification bias, their sequences must be extracted from the reads and added to the FASTQ header before alignment [2]. This prevents alignment interference.

Read trimming is then performed to remove:

- Adapter sequences: Leftover adapter contamination.

- Low-quality bases: Sequences with poor quality scores, often at read ends.

- Poly(A), poly(G), or homopolymer stretches: Poly(G) sequences are common artifacts in Illumina instruments using 2-channel chemistry [2].

Commonly used tools for this step include Trimmomatic and Cutadapt [2] [1].

Table 1: Key Steps and Tools in Primary Analysis

| Step | Description | Common Tools | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Base Calling & Demultiplexing | Converts BCL files to FASTQ; assigns reads to samples via barcodes | bcl2fastq, iDemux |

Sample-specific FASTQ files |

| Run QC | Assesses overall sequencing performance | Sequencing Analysis Viewer (Illumina) | Q30 scores, cluster density metrics |

| UMI Extraction | Removes UMI sequences from reads and adds to header | UMI-tools | FASTQ files with UMI in header |

| Read Trimming | Removes adapters, low-quality bases, and artifacts | Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, fastp |

Cleaned FASTQ files |

Secondary Analysis: Alignment and Quantification

Secondary analysis transforms cleaned sequence reads into quantitative gene expression data by aligning them to a reference genome and counting reads associated with genomic features [2] [3].

Read Alignment

The cleaned reads are aligned (mapped) to a reference genome or transcriptome to determine their genomic origin. This step identifies which genes or transcripts are expressed in the samples [1]. The choice of alignment tool can significantly impact the accuracy and efficiency of this process.

Common alignment tools include:

- STAR: A splice-aware aligner ideal for detecting alternatively spliced transcripts.

- HISAT2: A memory-efficient successor to TopHat2.

- TopHat2: One of the earlier widely used splice-aware aligners.

An alternative to traditional alignment is pseudo-alignment with tools like Kallisto or Salmon. These methods rapidly estimate transcript abundances without performing base-by-base alignment, offering significant speed advantages and reduced memory requirements [1].

Post-Alignment Quality Control

After alignment, a second quality control step is performed to identify and remove poorly aligned reads or those mapped to multiple locations (multi-mapped reads). This step is crucial because incorrectly mapped reads can artificially inflate read counts, leading to inaccurate gene expression estimates [1]. Tools for post-alignment QC include:

- SAMtools: Provides utilities for processing and viewing alignments.

- Qualimap: Generates comprehensive quality control reports for aligned data.

- Picard: A suite of tools for manipulating high-throughput sequencing data.

Read Quantification

The final step of secondary analysis quantifies expression levels by counting the number of reads mapped to each gene or transcript, generating a raw count matrix [1]. In this matrix, each row represents a gene, each column represents a sample, and the values indicate the number of reads assigned to that gene in that sample. A higher number of reads indicates higher expression of the gene [1]. Tools for this task include:

- featureCounts: Part of the Subread package, efficient for counting reads over genomic features.

- HTSeq-count: A popular Python-based counting utility.

Table 2: Key Steps and Tools in Secondary Analysis

| Step | Description | Common Tools | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Read Alignment | Maps reads to a reference genome/transcriptome | STAR, HISAT2, TopHat2 |

SAM/BAM alignment files |

| Pseudo-alignment | Estimates abundances without full alignment | Kallisto, Salmon |

Abundance estimates |

| Post-Alignment QC | Identifies poorly aligned or multi-mapped reads | SAMtools, Qualimap, Picard |

QC reports, filtered BAM files |

| Read Quantification | Counts reads associated with each gene | featureCounts, HTSeq-count |

Raw count matrix |

Tertiary Analysis: Extracting Biological Meaning

Tertiary analysis represents the final stage where quantitative data is transformed into biological insights through statistical analysis, visualization, and interpretation [2] [3]. This stage is highly flexible and tailored to the specific biological questions being investigated.

Data Normalization

The raw count matrix generated during secondary analysis cannot be directly compared between samples due to technical variations, particularly differences in sequencing depth (the total number of reads obtained per sample) [1]. Normalization mathematically adjusts these counts to remove such biases, enabling meaningful comparisons. Methods like TPM (Transcripts Per Million) and those implemented in tools such as DESeq2 and edgeR account for these technical factors to produce comparable expression values [1].

Differential Gene Expression (DGE) Analysis

A primary goal of many RNA-seq studies is to identify genes that are differentially expressed between conditions (e.g., treated vs. control, diseased vs. healthy) [1]. DGE analysis uses statistical models to identify genes with significant expression changes beyond what would be expected by random chance alone. The reliability of DGE analysis depends heavily on proper experimental design, particularly the inclusion of an adequate number of biological replicates [1]. While three replicates per condition is often considered a minimum standard, more replicates may be needed when biological variability is high [1].

Functional Enrichment and Pathway Analysis

Once a set of differentially expressed genes is identified, the next step is to interpret their biological significance. Gene Ontology (GO) term enrichment and gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) are common approaches that identify biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular pathways that are overrepresented in the gene list [2]. This moves the analysis from a gene-centric to a systems-biology perspective, revealing broader biological themes.

Data Visualization and Exploration

Effectively communicating findings is a critical aspect of tertiary analysis. Visualization techniques help distill complex data into comprehensible formats [2]. Common visualization methods include:

- Volcano plots: Display statistical significance vs. magnitude of change for all genes.

- Heatmaps: Visualize expression patterns of genes across samples or conditions.

- PCA (Principal Component Analysis) plots: Assess overall data structure and identify sample outliers or batch effects [4].

Table 3: Key Components and Tools in Tertiary Analysis

| Component | Description | Common Tools/Methods | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data Normalization | Adjusts counts for technical biases (e.g., sequencing depth) | TPM, DESeq2, edgeR | Normalized count matrix |

| Differential Expression | Identifies statistically significant expression changes | DESeq2, edgeR, limma | List of differentially expressed genes |

| Functional Enrichment | Interprets biological meaning of gene lists | GO analysis, GSEA | Enriched pathways/processes |

| Data Visualization | Creates informative data representations | PCA plots, heatmaps, volcano plots | Publication-quality figures |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful RNA-seq experiments require careful selection of reagents and kits tailored to the specific research goals, sample type, and input quantity. The table below details key solutions used in RNA-seq workflows.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq

| Reagent/Kit | Manufacturer/Vendor | Primary Function | Key Applications & Input Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|

| TruSeq Stranded mRNA Prep | Illumina | Library preparation from poly-A enriched RNA | Standard bulk RNA-seq; requires ≥100 ng total RNA [5] |

| NEBNext Ultra II Directional RNA | New England Biolabs | Library preparation for stranded RNA-seq | Bulk RNA-seq with low input (≥10 ng total RNA) [5] |

| Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004) | Oxford Nanopore Technologies | Sequences native RNA without cDNA conversion | Long-read sequencing; detects modified bases; requires 300 ng-1 µg total RNA [6] [5] |

| SMRTbell Prep Kit 3.0 | Pacific Biosciences | Library prep for Iso-Seq (full-length transcript sequencing) | Long-read sequencing for isoform detection; requires ≥300 ng total RNA [5] |

| MERCURIUS BRB-seq Kit | Alithea Genomics | 3'mRNA-seq with sample barcoding for pooling | High-throughput, cost-effective bulk profiling; works with 100 pg-1 µg RNA [5] |

| QIAseq UPXome RNA Library Kits | QIAGEN | Library prep for ultra-low input and degraded samples | Challenging samples (FFPE, sorted cells); works with 500 pg-100 ng RNA [5] |

| Agencourt RNAClean XP Beads | Beckman Coulter | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) bead-based clean-up | Size selection and purification of nucleic acids post-library prep |

Experimental Design and Quality Control Considerations

Foundational Experimental Design

The reliability of any RNA-seq analysis is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the experimental design. Two critical factors must be considered before sequencing begins:

- Biological Replicates: These are essential for capturing biological variability and enabling robust statistical inference. While a minimum of three replicates per condition is a common standard, studies with high inherent variability (e.g., human tissues) may require more to achieve sufficient statistical power [1]. Experiments with only one or two replicates severely limit the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates.

- Sequencing Depth: This refers to the number of reads sequenced per sample. For standard differential expression analysis in bulk RNA-seq, approximately 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient [1]. Deeper sequencing increases sensitivity for detecting lowly expressed transcripts but also increases cost.

Quality Control Checkpoints Across the Three Pillars

A comprehensive quality control strategy must be implemented throughout the entire workflow, not just at the beginning. The "garbage in, garbage out" principle is particularly relevant to RNA-seq; flawed data from early stages cannot be rescued by sophisticated tertiary analysis [2].

- Primary Analysis QC: Assess overall sequencing run performance (Q-scores, cluster density), and use tools like FastQC or MultiQC to evaluate raw read quality, adapter content, and nucleotide composition [2] [1].

- Secondary Analysis QC: Review alignment rates, the distribution of reads across genomic features (e.g., exons, introns), and identify potential contamination or biases using tools like Qualimap or Picard [1].

- Tertiary Analysis QC: Examine sample relationships using PCA plots to check for batch effects and ensure replicates cluster together. Investigate the distribution of normalized counts and the relationship between mean and variance across samples [4].

The field of RNA-seq analysis is continuously evolving. Key trends shaping its future include the rise of single-cell and spatial transcriptomics, which require specialized computational methods to handle increased complexity and scale [7] [8]. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning is enhancing variant calling, enabling more accurate cell type identification from single-cell data, and facilitating the prediction of treatment responses [7] [9]. Finally, the growing volume of sequencing data has made cloud computing platforms essential, providing the scalable storage and computational power necessary for modern large-scale genomic studies [7].

The three-pillar framework of RNA-seq analysis provides a systematic and quality-controlled pathway from raw sequencing data to biological discovery. Primary analysis converts raw signals into processed reads, secondary analysis aligns and quantifies these reads, and tertiary analysis extracts biological insights through statistical testing and interpretation. A thorough understanding of each stage, coupled with rigorous experimental design and continuous quality control, is paramount for generating reliable, reproducible results that can advance scientific knowledge and drug development efforts. As technologies and computational methods continue to advance, this foundational framework ensures that researchers can confidently navigate the complexities of transcriptomic data.

In next-generation sequencing (NGS), the quality score, or Q-score, is a fundamental metric that predicts the probability of an incorrect base call. Defined by the Phred algorithm, the quality score (Q) is logarithmically related to the base-calling error probability (e). The equation Q = -10 × log10(e) means that each quality score represents a tenfold change in error probability [10] [11]. For example, a base with a Q-score of 30 (Q30) has an error probability of 1 in 1,000, translating to a base call accuracy of 99.9% [10]. This relationship establishes Q30 as a critical benchmark in sequencing quality, indicating that virtually all reads will be perfect with no errors or ambiguities when this threshold is achieved [10].

The assignment of quality scores during sequencing involves complex computational processes. For Illumina platforms, the system evaluates light signals for each base call, measuring parameters like signal-to-noise ratio and intensity to calculate a quality predictor value (QPV) [11]. This QPV is then translated into a Phred quality score using a calibration table derived from empirical data [11]. These quality scores are stored alongside base calls in FASTQ files, where they are encoded as single ASCII characters to conserve space [12] [11]. The fourth line of each FASTQ entry contains this quality string, with each character representing the quality score for the corresponding base in the sequence [11].

In the context of RNA sequencing (RNA-seq), quality assessment extends beyond individual base calls to encompass multiple analysis stages. A comprehensive RNA-seq quality control strategy should address four critical perspectives: RNA quality assessment, evaluation of raw read data in FASTQ format, alignment quality metrics, and gene expression data quality [13]. Within this framework, Q30 scores serve as a fundamental checkpoint at the raw data level, providing the first indication of whether sequencing performance meets the standards required for reliable downstream analysis [2] [13].

The Critical Role of Q30 in RNA-Seq Quality Control

Interpreting Q-Score Values

Understanding the relationship between quality scores and error probabilities is essential for proper sequencing quality assessment. The table below summarizes this relationship for common Q-score thresholds:

Table 1: Quality Score Interpretation

| Quality Score | Probability of Incorrect Base Call | Base Call Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Q10 | 1 in 10 | 90% |

| Q20 | 1 in 100 | 99% |

| Q30 | 1 in 1,000 | 99.9% |

| Q40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% |

| Q50 | 1 in 100,000 | 99.999% |

Data compiled from [10] [14] [11]

The progression from Q20 to Q30 represents a significant improvement in data quality. While Q20 data (99% accuracy) may contain a substantial number of errors that compromise downstream analysis, Q30 data (99.9% accuracy) provides the reliability required for most research applications [10]. For clinical research, where accuracy requirements are more stringent, higher thresholds such as Q40 or even Q50 may be necessary, particularly for detecting low-frequency variants [14].

Impact on RNA-Seq Data Interpretation

In RNA-seq experiments, suboptimal quality scores can lead to multiple interpretive challenges. Lower Q-scores result in a higher probability of base-calling errors, which directly impacts variant calling accuracy and increases false-positive rates [10] [15]. This is particularly problematic when working with low-abundance transcripts or detecting rare splice variants, where sequencing errors can be misinterpreted as biological signals [16].

The percentage of bases above Q30 (%Q30) serves as a key quality indicator for sequencing runs. For example, Illumina specifies that for a NextSeq500 run in high-output paired-end 75 mode, at least 80% of bases should achieve Q30 or higher [2]. Failure to meet this threshold suggests potential issues with library preparation, cluster density, or sequencing chemistry that may compromise data integrity [2]. For clinical applications, where detecting mutations at low variant allele frequencies (VAF) is often critical, the stringent quality requirements make Q30 assessment even more important [15].

Practical Assessment of Sequencing Run Quality

Experimental Protocol for Quality Assessment

Implementing a systematic approach to sequencing quality assessment is essential for generating reliable RNA-seq data. The following workflow outlines key assessment steps:

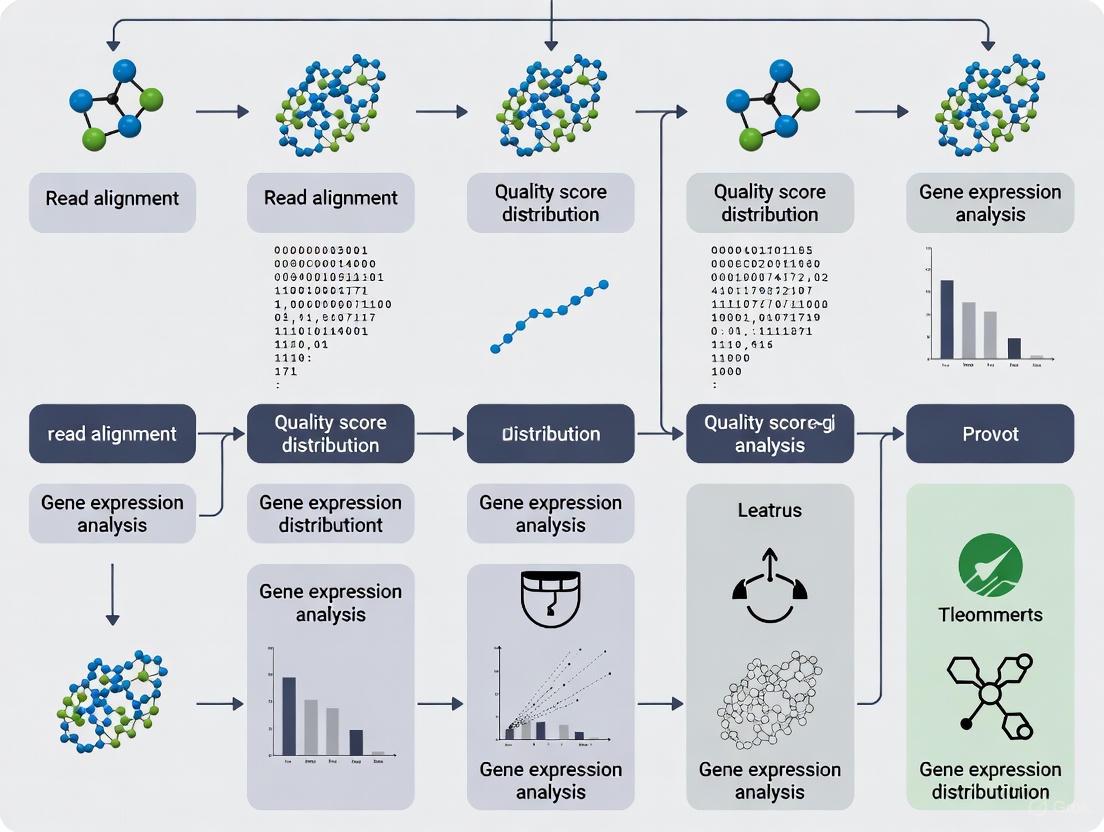

Figure 1: Workflow for sequencing run quality assessment. The process begins with sequencing run completion and progresses through primary analysis stages to generate a comprehensive data quality report.

The initial quality assessment begins with base calling and demultiplexing, where binary BCL files are converted to FASTQ format [2]. During this process, quality scores are assigned to each base and encoded in the FASTQ files [11]. For RNA-seq data, the RNA-SeQC tool provides comprehensive quality control measures, including yield, alignment and duplication rates, GC bias, rRNA content, regions of alignment, coverage continuity, and 3'/5' bias [16]. These metrics help researchers make informed decisions about sample inclusion in downstream analysis [16].

Quality Verification Methods

While sequencing platforms assign initial quality scores, verification of these scores through empirical methods is crucial. Base call quality recalibration (BQSR) tools, available in packages like the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK), compare predicted quality scores to empirically observed accuracy [14]. This process involves considering all bases assigned to a particular quality score and using alignment to determine the empirical error rate in that population [14]. If the empirical error rate matches the predicted rate (e.g., 1 error per 1,000 bases for Q30), the quality scores are considered accurate. Discrepancies indicate overprediction or underprediction of quality, requiring appropriate adjustments [14].

For calculating mean quality scores in sequencing data, specialized tools implement specific algorithms. The Dorado basecaller, for example, calculates mean Q-score by first trimming the leading 60 bases to account for initial noise, converting the remaining Q-scores to error probabilities, calculating the mean of these probabilities, and finally converting this mean back to a Q-score [12]. This approach acknowledges the higher noise typically present at the beginning of sequencing reads [12].

Integrating Q30 Assessment with Broader RNA-Seq QC

Comprehensive RNA-Seq Quality Framework

While Q30 assessment provides crucial information about base-calling accuracy, it represents just one component of a comprehensive RNA-seq quality control strategy. The multi-perspective QC approach encompasses four interrelated stages [13]:

- RNA Quality: RNA integrity is the most fundamental requirement for generating quality data, as degraded starting material cannot be compensated for by subsequent steps.

- Raw Read Data (FASTQ): Beyond Q-scores, this stage should evaluate total read count, GC content, adapter contamination, and sequence duplication.

- Alignment Metrics: Assessment should include alignment rates, distribution of alignments across genomic features, and strand-specificity for strand-specific protocols.

- Gene Expression: Unsupervised clustering and correlation analysis help identify sample outliers and technical artifacts.

Within this framework, tools like RNA-SeQC provide critical quality measures, including the expression profile efficiency (ratio of exon-mapped reads to total reads sequenced) and strand specificity metrics that assess the performance of strand-specific library construction methods [16].

Addressing Coverage and Specific Error Modes

Quality assessment must also consider sequencing depth, as insufficient coverage can lead to false negatives in variant detection [15]. The required depth depends on the intended limit of detection (LOD), tolerance for false positives/negatives, and the overall error rate of the sequencing assay [15]. For clinical applications where detecting low-frequency variants is critical, higher coverage depths are necessary to distinguish true variants from sequencing errors [15].

Different error modes require specific attention. Deamination damage, often manifesting as C→T errors, can be addressed using deamination reagents that digest damaged fragments prior to sequencing [14]. End repair errors, which predominantly affect the initial cycles of Read 2, can be mitigated through "dark cycling" that skips base calling in problematic regions [14]. For Illumina platforms using 2-channel chemistry, poly(G) sequences resulting from absent signals should be trimmed prior to alignment [2].

Research Reagent Solutions for Quality Optimization

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for RNA-Seq Quality Control

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| PhiX Control | In-run control for sequencing quality monitoring | Provides a quality baseline for Illumina sequencing runs [10] |

| RNA-SeQC | Comprehensive quality control metrics for RNA-seq | Provides alignment statistics, coverage uniformity, GC bias, and expression correlation [16] |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | Sample multiplexing with error correction | Enables accurate demultiplexing and recovery of reads with index errors [2] |

| Deamination Reagents | Digest fragments with deamination damage | Reduces C→T errors caused by library preparation [14] |

| Cloudbreak UltraQ Chemistry | High-accuracy sequencing chemistry | Enables Q50+ sequencing for low-frequency variant detection [14] |

| iDemux | Demultiplexing with error correction | Maximizes data output by rescuing reads with index errors [2] |

| Trimmomatic/cutadapt | Read trimming and adapter removal | Removes adapter sequences, poly(G) tails, and low-quality bases [2] |

Rigorous assessment of sequencing run quality using Q30 scores represents a non-negotiable first step in RNA-seq data analysis. This pre-analysis quality check serves as the foundation for all subsequent biological interpretations, enabling researchers to distinguish technical artifacts from true biological signals. By implementing a comprehensive quality assessment strategy that integrates Q30 evaluation with broader QC metrics, researchers can ensure the generation of reliable, reproducible RNA-seq data capable of supporting robust scientific conclusions. In clinical contexts, where diagnostic and treatment decisions may rely on sequencing results, this rigorous approach to quality assessment becomes even more critical for maintaining analytical validity and protecting patient interests.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, with RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) becoming the de facto standard for transcriptome profiling. The journey from raw data to biologically meaningful results begins with understanding the fundamental file formats that store sequencing data. This technical guide provides an in-depth examination of the progression from raw binary base call (BCL) files to the standardized FASTQ format, including detailed interpretation of quality scores that determine data reliability. Framed within the context of RNA-seq quality control, this whitepaper serves as an essential resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals seeking to ensure data integrity in their genomic analyses.

The transformation of raw sequencing signals into analyzable genetic data involves multiple file formats, each serving a distinct purpose in the data processing pipeline. Illumina sequencing systems, which dominate the NGS landscape, initially generate data in proprietary binary formats that must be converted for downstream analysis [17]. This conversion process represents a critical first step in RNA-seq quality control, as inaccuracies at this stage can compromise all subsequent analyses and lead to flawed biological conclusions.

In RNA-seq experiments, the quality of primary data analysis directly impacts the reliability of differential expression results, variant calling, and transcriptome assembly. The file formats discussed herein—BCL and FASTQ—form the foundation upon which all secondary and tertiary analyses are built. Understanding their structure, generation, and quality metrics is therefore paramount for researchers working with transcriptomic data, particularly in drug development contexts where results may inform clinical decisions [2].

BCL Format: The Raw Data Foundation

Definition and Generation

Binary Base Call (BCL) files represent the most primitive data format generated by Illumina sequencing instruments. During sequencing by synthesis (SBS) chemistry, the Real Time Analysis (RTA) software on the instrument makes base calls for each cluster on the flow cell for every cycle of sequencing [18]. These base calls and their associated confidence scores are stored in real-time as BCL files—binary files that efficiently record the sequencing results as they occur [19].

The BCL format stores data in a highly compact binary structure, with each base and its corresponding quality score recorded for every sequencing cycle and every location (tile) on the flow cell lanes [19]. This efficient storage mechanism allows the sequencer to handle the massive data throughput of modern NGS platforms like the NovaSeq 6000, NextSeq, and HiSeq systems [17].

File Organization and Structure

BCL files follow a specific organizational hierarchy within the sequencing run directory:

Individual BCL files are named according to the pattern: s_<lane>_<tile>.bcl [19]. Each file contains the base calls for a specific tile within a lane for a single sequencing cycle. This organization reflects the physical layout of the flow cell and enables parallel processing during conversion to FASTQ format.

Table 1: BCL File Organization Components

| Component | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Run Directory | Top-level folder containing all data from a sequencing run | 231015_M00123_0456_000000000-ABCDE |

| Lane | Physical lane on the flow cell (1-8 for most instruments) | L001 to L008 |

| Cycle | Sequencing cycle number | C001.1 to C300.1 |

| Tile | Subsection within a lane where clusters are located | s_1_1101.bcl |

FASTQ Format: The Analysis-Ready Standard

Definition and Structure

FASTQ has emerged as the standard file format for storing NGS sequence data and quality scores, providing a text-based representation that is compatible with most downstream analysis tools [17] [20]. Developed at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, FASTQ effectively bundles a FASTA-formatted sequence with its corresponding quality data in a single file [20] [21].

A FASTQ file contains four lines per sequence entry:

- Sequence identifier: Begins with a '@' character, followed by a unique sequence identifier and optional description

- Raw sequence letters: The actual base calls (A, C, T, G, N)

- Separator: A '+' character, optionally followed by the same sequence identifier

- Quality scores: Encoded quality values for each base in the sequence, using ASCII characters [20]

The example above shows a typical FASTQ entry with its four constituent lines [20].

Illumina Sequence Identifiers

Illumina sequencing software employs systematic identifiers that encode valuable information about the sequencing run:

Pre-Casava 1.8 Format:

@HWUSI-EAS100R:6:73:941:1973#0/1

Casava 1.8+ Format:

@EAS139:136:FC706VJ:2:2104:15343:197393 1:Y:18:ATCACG

Table 2: Components of Illumina Sequence Identifiers

| Component (Casava 1.8+) | Description | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Instrument ID | Unique instrument name | EAS139 |

| Run ID | Sequencing run identifier | 136 |

| Flowcell ID | Unique flowcell identifier | FC706VJ |

| Flowcell Lane | Lane number on flowcell | 2 |

| Tile Number | Tile within the flowcell lane | 2104 |

| Cluster Coordinates | x and y coordinates of the cluster within the tile | 15343:197393 |

| Read Member | Member of a pair (1 or 2 for paired-end) | 1 |

| Filter Status | Y if filtered (did not pass), N otherwise | Y |

| Control Number | 0 when no control bits are on | 18 |

| Index Sequence | Sample index sequence | ATCACG |

Quality Score Encoding

Quality scores in FASTQ files represent the probability of an incorrect base call, using the Phred quality score formula: Q = -10 × log₁₀(P), where P is the estimated probability of the base call being wrong [21]. A quality score of 30 (Q30) indicates a 1 in 1000 chance of an incorrect base call, equivalent to 99.9% accuracy [2].

Three main encoding variants exist for quality scores in FASTQ files:

Table 3: FASTQ Quality Score Encoding Variants

| Variant | ASCII Range | Offset | Quality Score Range | Typical Usage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sanger (standard) | 33-126 | 33 | 0 to 93 | Sanger capillary sequencing, modern Illumina |

| Solexa/Early Illumina | 59-126 | 64 | -5 to 62 | Early Solexa/Illumina pipelines |

| Illumina 1.3+ | 64-126 | 64 | 0 to 62 | Illumina Pipeline 1.3-1.7 |

The Sanger format (Phred+33 encoding) has become the standard for modern Illumina data, using ASCII characters 33 to 126 to represent quality scores from 0 to 93 [21]. The quality string must contain exactly the same number of characters as the sequence string, providing a per-base quality measurement [20].

The BCL to FASTQ Conversion Process

Conversion Methodology

The conversion from BCL to FASTQ format is a critical first step in NGS data analysis, typically performed using Illumina's bcl2fastq or DRAGEN BCL Convert software [17] [18]. This process involves multiple coordinated steps:

- Demultiplexing: Assignment of sequences to samples based on their index (barcode) sequences

- Sequence Extraction: Conversion of binary base calls to nucleotide sequences

- Quality Score Assignment: Attachment of quality scores to each base in the sequence

- File Organization: Writing of sequences and quality scores to FASTQ files in the standard four-line format

For single-read sequencing runs, one FASTQ file is created per sample per lane. For paired-end runs, two FASTQ files (R1 and R2) are generated for each sample per lane [18]. The files are typically compressed using gzip, resulting in the common .fastq.gz file extension.

BCL to FASTQ Conversion Workflow

Demultiplexing Strategies

In multiplexed sequencing runs, where multiple samples are pooled on a single flow cell lane, demultiplexing is an essential component of the BCL to FASTQ conversion process. This step sorts sequences into sample-specific FASTQ files based on their index sequences [2]. Advanced demultiplexing tools like Lexogen's iDemux can perform error correction on index sequences, salvaging reads that would otherwise be lost due to sequencing errors in the barcode region [2].

Dual index sequencing (using indices on both ends of the fragment) provides the highest demultiplexing accuracy by enabling error detection and correction in both index reads. Sophisticated unique dual index (UDI) designs further enhance demultiplexing accuracy by minimizing index hopping and cross-talk between samples [2].

Quality Control in RNA-seq Analysis

Primary Analysis Quality Metrics

In RNA-seq experiments, quality assessment begins immediately after FASTQ file generation. Primary analysis quality control focuses on several key metrics:

- Q-score Distribution: The percentage of bases with quality scores above Q30 (99.9% accuracy) is a critical quality threshold [2]

- Reads Passing Filter (PF): The proportion of clusters that pass Illumina's internal "chastity filter" applied during the first 25 cycles [2]

- GC Content: Deviation from expected GC distribution may indicate contamination or bias

- Adapter Contamination: Presence of adapter sequences indicates insufficient fragment sizes

For Illumina sequencers using 2-channel chemistry (NextSeq, NovaSeq), special attention should be paid to poly(G) sequences that result from absence of signal, which defaults to G calls. These sequences should be trimmed prior to alignment [2].

RNA-seq Specific Quality Assessment

Specialized tools like RNA-SeQC provide comprehensive quality metrics specific to transcriptome sequencing [16]. These include:

- Alignment Metrics: Mapping rates, ribosomal RNA content, and strand specificity

- Coverage Uniformity: 5'/3' bias, coverage continuity, and gap analysis

- Expression Correlation: Comparison to reference expression profiles

- Transcript Detection: Count of detectable transcripts and expression profile efficiency

RNA-SeQC generates both HTML reports for manual inspection and tab-delimited files for pipeline integration, enabling automated quality assessment in large-scale RNA-seq studies [16].

Table 4: Essential RNA-seq Quality Metrics

| Metric Category | Specific Metrics | Target Values |

|---|---|---|

| Read Counts | Total reads, mapped reads, rRNA content | >70% alignment, <5% rRNA |

| Duplicate rates, strand specificity | <20% duplicates, >99% sense for strand-specific | |

| Coverage | Mean coverage, 5'/3' bias, gap length | Uniform coverage, minimal bias |

| Expression | Detectable transcripts, correlation to reference | High correlation to expected profile |

| Sequencing Performance | Q30 scores, GC bias, insert size distribution | >80% Q30, normal GC distribution |

Advanced Topics in Sequence Data Management

Compression Technologies

With RNA-seq datasets growing increasingly large, efficient compression technologies have become essential for feasible data storage and transfer. Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated specialized compression tools for NGS data:

Table 5: Compression Software for Short-Read Sequence Data

| Software | Compression Ratio | Speed | Supported Formats | License |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DRAGEN ORA | 1:5.64 | Very Fast | FASTQ | Commercial |

| Genozip | 1:5.99 | Fast | FASTQ, BAM, CRAM, gVCF | Freemium |

| SPRING | 1:3.79 | Slow | FASTQ | Free |

| repaq | 1:1.99 | Very Slow | FASTQ | Free |

DRAGEN ORA, a newer compression format from Illumina, provides lossless compression that reduces file sizes up to 5 times compared to standard FASTQ.GZ files without compromising data integrity [17] [22]. This technology is particularly valuable for large-scale RNA-seq studies where storage costs can become prohibitive.

Rapid Quality Assessment Tools

Traditional quality assessment methods that require full alignment can take hundreds of CPU hours. Newer tools like FASTQuick address this bottleneck by providing comprehensive quality metrics without full alignment, offering 30-100x faster turnaround while still estimating critical metrics like:

- Mapping rates and depth distribution

- GC bias and PCR duplication rates

- Sample contamination and genetic ancestry

- Insert size distribution [23]

This rapid assessment enables real-time quality evaluation at the beginning of analysis pipelines, preventing wasted resources on compromised datasets.

Experimental Protocols for RNA-seq Quality Control

Standardized QC Workflow

A robust RNA-seq quality control protocol should incorporate these essential steps:

- Sequencing Run QC: Assess run performance using instrument-specific metrics including cluster density, total output, and % bases ≥Q30 [2]

- BCL to FASTQ Conversion: Convert raw data using bcl2fastq or DRAGEN BCL Convert with appropriate demultiplexing parameters [17] [18]

- Read Trimming: Remove adapter sequences, poly(A)/poly(G) tails, and low-quality bases using tools like cutadapt or Trimmomatic [2]

- UMI Processing: For UMI-based protocols, extract molecular identifiers and add to read headers before alignment [2]

- Comprehensive QC Assessment: Run RNA-SeQC or similar tools to generate alignment statistics, coverage metrics, and contamination estimates [16]

- Data Compression: Apply appropriate compression technology (e.g., DRAGEN ORA) for long-term storage [22]

The Researcher's Toolkit

Table 6: Essential Tools for RNA-seq Data Processing and QC

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| BCL to FASTQ Conversion | bcl2fastq, DRAGEN BCL Convert, bcl2fastq2 | Convert raw BCL files to analysis-ready FASTQ |

| Demultiplexing | bcl2fastq, iDemux | Sort sequences by sample using index barcodes |

| Read Trimming | cutadapt, Trimmomatic | Remove adapters and low-quality sequences |

| Quality Assessment | FastQC, RNA-SeQC, FASTQuick | Generate QC metrics and reports |

| UMI Processing | UMI-tools, zUMIs | Extract and handle unique molecular identifiers |

| Data Compression | DRAGEN ORA, Genozip, SPRING | Compress sequence files for efficient storage |

The journey from BCL to FASTQ represents a critical transformation in RNA-seq data analysis, converting proprietary instrument data into a standardized format accessible to diverse analysis tools. Understanding this process—including quality score interpretation, proper demultiplexing, and comprehensive quality assessment—forms the essential foundation for reliable transcriptomic research.

As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve toward higher throughput and broader applications, the principles outlined in this guide will remain fundamental to ensuring data quality. By implementing rigorous quality control protocols at the file format level, researchers can detect issues early, prevent wasted resources, and build their downstream analyses on a foundation of trustworthy sequence data. This is particularly crucial in drug development contexts, where decisions with significant clinical implications may hinge on accurate genomic data interpretation.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has become a cornerstone of modern transcriptomics, enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance. However, the reliability of the biological insights gained is directly dependent on the quality of the underlying data. For researchers and drug development professionals, ensuring data integrity is not merely a technical formality but a critical step that prevents misleading conclusions, wasted resources, and compromised study validity. A rigorous quality control (QC) protocol is essential, focusing on key metrics that reflect the success of the wet-lab and computational processes. This guide details the three core QC metrics—Mapping Rates, rRNA Content, and Library Complexity—that every researcher must monitor to ensure their RNA-Seq data is robust and biologically sound.

Mapping Rates: Gauging Data Utility and Purity

The mapping rate, or the percentage of sequencing reads that successfully align to a reference genome or transcriptome, is a primary indicator of data quality and potential contamination.

Interpretation and Benchmarking

Mapping rates provide a quick assessment of how much of your sequencing data corresponds to the expected biological source. Table 1 summarizes the benchmarks and interpretations for this metric.

Table 1: Interpretation of Mapping Rates

| Mapping Rate | Interpretation | Potential Causes & Actions |

|---|---|---|

| ≥ 90% | Ideal [24] | Indicates high-quality data, proper library preparation, and correct reference selection. |

| ~70% | Acceptable [24] | May be typical for samples with lower RNA quality or for less complete reference genomes (e.g., non-model organisms). |

| < 70% | Cause for Concern [25] | Suggests potential issues such as sample contamination, poor read quality, highly degraded RNA, or an incorrect/incomplete reference genome. |

Experimental Protocols and Troubleshooting

Low mapping rates necessitate a systematic investigation. A highly recommended first step is to BLAST a subset of the unmapped reads to identify their biological origin, which can reveal contamination from foreign species or other sources [24].

Beyond the overall rate, the distribution of mapped reads across genomic features is highly informative. This is assessed using tools like RSeQC or Picard [24] [25]. The expected distribution is heavily influenced by the library preparation method:

- Poly(A) Enrichment: Most reads should map to exonic regions, with low percentages in intronic and intergenic spaces, as this method captures mature mRNAs [24].

- rRNA Depletion (Total RNA): A higher fraction of reads mapping to introns and intergenic regions is expected, as this method also captures pre-mature mRNAs and non-coding RNAs [24].

- 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq): Reads should be heavily concentrated towards the 3' UTR of transcripts. A more even distribution across transcripts may indicate RNA degradation [24].

rRNA Content: Measuring Library Efficiency

Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) constitutes 80-98% of the total RNA in a cell. Since most studies focus on messenger RNA (mRNA) or other non-ribosomal RNAs, efficient depletion or avoidance of rRNA is crucial for a cost-effective and informative sequencing experiment [26] [27].

Interpretation and Benchmarking

The residual rRNA content is a direct measure of the efficiency of the rRNA removal step during library preparation. Table 2 outlines typical values and their implications.

Table 2: Interpretation of Residual rRNA Content

| rRNA Content | Interpretation | Library Prep Method |

|---|---|---|

| ~3-5% | Typical and Acceptable [24] | Common for 3' mRNA-Seq (e.g., QuantSeq) due to capture of mitochondrial rRNAs. |

| < 1% | Ideal / High Efficiency [24] | Achieved with effective rRNA-depleted workflows (e.g., RiboCop). |

| > 10% | Inefficient Depletion / Low Complexity [24] [27] | Suggests inefficient rRNA depletion, which wastes sequencing reads and can mask lower-abundance transcripts. |

Experimental Protocols and Method Selection

The two primary methods for managing rRNA are poly(A) selection and ribosomal depletion (ribodepletion). The choice depends on the research question and RNA quality:

- Poly(A) Selection: Uses oligo(dT) to capture mRNAs with poly(A) tails. This is inefficient if the RNA is degraded, as the poly(A) tail may be lost [26].

- Ribodepletion: Uses probes to hybridize and remove rRNA sequences. This is more suitable for degraded RNA samples (e.g., from FFPE tissues) or for studying non-polyadenylated RNAs [26]. Studies show that ribodepletion protocols can vary in reproducibility and efficiency, and some may have off-target effects on certain genes of interest [26].

The rRNA content can be calculated from the output of quantification tools if the genome annotation includes rRNA sequences. For a more comprehensive or annotation-free approach, tools like RNA-QC-Chain can directly filter rRNA reads by comparing them to rRNA sequence databases like SILVA [28].

Library Complexity: Assessing Transcriptome Diversity

Library complexity refers to the number of unique RNA molecules represented in the sequenced library. High-complexity libraries, which capture a diverse set of transcripts, are essential for a comprehensive view of the transcriptome.

Interpretation and Key Metrics

Complexity is most directly measured by the number of unique genes or transcripts detected at a specific sequencing depth [27]. A low number of detected genes indicates low complexity, meaning the library is dominated by a small subset of transcripts.

Another metric related to complexity is the duplication rate. While some duplication is expected for highly expressed genes, a high overall duplication rate often indicates a high level of PCR amplification from a limited starting amount of unique RNA fragments, a sign of low complexity [25] [27].

Experimental Protocols and Influencing Factors

Library complexity is profoundly affected by upstream wet-lab procedures. Key factors include:

- RNA Input Quality and Quantity: Using low amounts of input RNA or highly degraded RNA is a primary cause of low complexity, as it reduces the diversity of the starting template [24] [26]. A high-quality RNA sample should have an RNA Integrity Number (RIN) greater than 7 [26].

- rRNA Content: As previously discussed, a high percentage of rRNA reads directly reduces the sequencing capacity available for informative transcripts, leading to lower detected gene counts [24].

- PCR Amplification: Excessive PCR cycles during library prep can lead to over-amplification of a limited set of molecules, artificially inflating duplication rates and reducing complexity [25].

To accurately diagnose the cause, it is useful to examine the relationship between sequencing depth and the number of genes detected. A complex library will show a steady increase in gene detection with added sequencing, which will eventually plateau. A library that plateaus quickly is likely of low complexity.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential QC Solutions

The following table lists key reagents, tools, and resources essential for implementing a robust RNA-Seq QC protocol.

Table 3: Research Reagent and Tool Solutions for RNA-Seq QC

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in QC |

|---|---|---|

| Spike-in Controls (e.g., ERCC, SIRVs) | Synthetic RNA | Provides a ground-truth dataset for benchmarking quantification accuracy, detection limits, and workflow performance [24]. |

| Ribodepletion Kits (e.g., RiboCop) | Biochemical Reagent | Selectively removes ribosomal RNA to increase the proportion of informative reads in the library [24]. |

| FastQC / MultiQC | Software | FastQC performs initial quality assessment of raw FASTQ files. MultiQC aggregates and summarizes results from multiple tools and samples into a single report [1] [25]. |

| RSeQC | Software | Provides RNA-specific QC metrics, including read distribution across genomic features, gene body coverage, and junction saturation [24] [25]. |

| Picard Tools | Software | A set of command-line tools for handling sequencing data, useful for metrics like duplication rates and insert size distributions [24] [25]. |

| RNA-QC-Chain | Software | A comprehensive pipeline that performs sequencing-quality trimming, rRNA filtering, and alignment statistics reporting in an integrated and efficient manner [28]. |

Integrated QC Workflow and Data Interpretation

A robust QC strategy integrates these metrics at multiple stages of the analysis pipeline. The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for monitoring these core metrics and the associated decision points.

Furthermore, the relationship between these metrics and sequencing depth is critical for experimental design. The following diagram models how key QC metrics typically behave as sequencing depth increases, helping to distinguish true technical issues from under-sequencing.

Mapping rates, rRNA content, and library complexity are non-negotiable pillars of RNA-Seq quality control. Systematically monitoring these metrics provides a powerful framework for diagnosing issues in experimental execution, informing data interpretation, and ultimately ensuring the biological conclusions drawn are built upon a foundation of reliable data. As RNA-Seq continues to play a pivotal role in basic research and drug development, integrating these QC practices is essential for generating reproducible, accurate, and scientifically valid results.

RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) has revolutionized transcriptome profiling, enabling genome-wide quantification of RNA abundance with high resolution and sensitivity [1]. However, the powerful biological insights it offers are entirely dependent on the quality of the input data. The principle of "Garbage In, Garbage Out" is particularly relevant to RNA-Seq analysis, where fundamental flaws introduced during early experimental stages or initial data processing can propagate through the entire analytical pipeline, ultimately leading to invalid biological conclusions [2]. Unlike largely experimental benchwork, RNA-Seq analysis demands proficiency with computational and statistical approaches to manage technical issues inherent in large, complex datasets [1]. This technical guide outlines a rigorous quality control (QC) framework for RNA-Seq experiments, providing researchers and drug development professionals with essential methodologies to ensure data integrity from sequencing to statistical analysis.

The challenges of RNA-Seq data quality stem from multiple potential sources of bias and technical artifacts. These include nucleotide composition biases, read-position biases, library preparation artifacts, gene length and sequencing depth biases, and confounding combinations of technical and biological variability [29]. Without systematic quality assessment at each step, researchers risk basing conclusions on technical artifacts rather than biological truth. This guide synthesizes current best practices into a comprehensive QC checklist, enabling researchers to maximize the value of their RNA-Seq data while avoiding common pitfalls that compromise data interpretation.

RNA-Seq QC Framework: A Stage-by-Stage Approach

Experimental Design and Sequencing QC

Robust RNA-Seq analysis begins with thoughtful experimental design long before sequencing occurs. Key considerations include biological replication, sequencing depth, and randomization to avoid batch effects. With only two replicates, differential expression analysis is technically possible but the ability to estimate variability and control false discovery rates is greatly reduced [1]. While three replicates per condition is often considered the minimum standard, this number may be insufficient when biological variability within groups is high [1]. For standard differential gene expression analysis, approximately 20-30 million reads per sample is often sufficient, though requirements vary by application [1].

Sequencing performance itself must be verified before proceeding with analysis. The overall quality score (Q30) - a measure of the percentage of bases called with a quality score of 30 or higher (indicating 99.9% base calling accuracy) - should be monitored against platform-specific specifications [2]. For Illumina platforms, cluster densities and reads passing filter (PF) should fall within manufacturer specifications, as over- and under-clustering can significantly decrease data quality [2].

Table 1: Key Sequencing Run Quality Metrics

| Metric | Target Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Q30 Score | >80% of bases | Indicates base calling accuracy of 99.9% |

| Cluster Density | Platform-specific (e.g., 129-165 k/mm² for NextSeq500) | Outside optimal range reduces data quality |

| Reads Passing Filter | Maximize percentage | Removes unreliable clusters early in analysis |

Primary Analysis: Raw Read Quality Control

After base calling and demultiplexing, which sorts reads into sample-specific FASTQ files based on their index (barcode) sequences, the first critical QC checkpoint occurs [2]. Tools like FastQC generate detailed reports for each FASTQ file, summarizing key metrics that help identify potential issues arising from library preparation or sequencing [30]. The MultiQC tool can then aggregate these reports across multiple samples for comparative assessment [1].

Key modules in FastQC reports require careful interpretation:

- Per-base sequence quality: Quality scores should remain predominantly in the green (good quality) zone, with possible gradual degradation toward read ends [30].

- Per-base sequence content: The first few bases often show non-random composition due to priming sequences, which is common in RNA-seq libraries though sometimes flagged by FastQC [30].

- Adapter content: High levels of adapter sequences indicate incomplete removal during library preparation and necessitate trimming [30].

- Sequence duplication levels: In single-cell RNA-seq or UMI-based protocols, high duplication is expected due to PCR amplification and highly expressed genes [30].

When issues are identified, read trimming tools such as Trimmomatic or Cutadapt clean the data by removing low-quality regions, adapter sequences, and other artifacts [1] [2]. For sequencing platforms using 2-channel chemistry, trimming of poly(G) sequences is particularly important, as these result from absence of signal and default to G calls [2].

Table 2: Essential FastQC Modules and Interpretation Guidelines

| FastQC Module | Expected Pattern in High-Quality Data | Common Deviations and Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Per-base sequence quality | Quality scores predominantly in green zone | Quality drops at read ends may require trimming |

| Per-base sequence content | Fairly uniform lines after initial bases | Initial base fluctuations normal in RNA-seq; consistent bias problematic |

| Adapter content | Minimal adapter sequences detected | High levels require additional trimming with specialized tools |

| Sequence duplication levels | Majority of sequences at low duplication | High duplication expected in single-cell and UMI protocols |

Alignment and Mapping QC

Following read cleaning, sequences are aligned to a reference genome or transcriptome using splice-aware aligners such as STAR or HISAT2, or alternatively through pseudo-alignment with tools like Kallisto or Salmon [1] [31]. Each approach has distinct advantages: traditional alignment facilitates comprehensive QC metrics, while pseudo-alignment offers speed and efficiency for large datasets [31].

Post-alignment QC is essential because incorrectly mapped reads can artificially inflate expression estimates. Tools like RNA-SeQC provide comprehensive quality metrics including alignment rates, ribosomal RNA content, read distribution across genomic features, and coverage uniformity [16] [32]. These metrics help identify potential issues such as:

- * ribosomal RNA contamination*: High rRNA reads suggest inefficient mRNA enrichment.

- Biased genomic distribution: Unexpected distributions between exonic, intronic, and intergenic regions may indicate RNA degradation or contamination.

- Strand-specificity issues: For strand-specific protocols, sense/antisense ratios should approach 99%/1% rather than the 50%/50% expected in non-strand-specific protocols [16].

- Coverage uniformity: 3'/5' bias may indicate degraded RNA, as 3' ends of transcripts are overrepresented in partially degraded samples.

For single-cell RNA-seq experiments, additional considerations include the accurate identification of cell barcodes associated with viable cells and proper handling of unique molecular identifiers (UMIs) to account for amplification bias [30] [33].

Count-Level Quality Assessment

After read quantification produces a gene count matrix, sample-level and gene-level QC must be performed before differential expression analysis. The raw counts cannot be directly compared between samples due to differences in sequencing depth and other technical biases, making normalization essential [1].

For single-cell RNA-seq, cell QC is typically performed based on three key covariates: the number of counts per barcode (count depth), the number of genes per barcode, and the fraction of counts from mitochondrial genes [33]. Barcodes with low count depth, few detected genes, and high mitochondrial fraction often represent dying cells or empty droplets, while those with unexpectedly high counts and gene numbers may represent doublets [33]. These covariates should be considered jointly rather than in isolation, as any single metric can be misleading [33].

In bulk RNA-seq, sample-level outliers can be detected using principal component analysis (PCA), which reduces the gene dimensionality to a minimal set of components reflecting the total variation in the dataset [4]. In a well-controlled experiment, samples should cluster by experimental group rather than by batch or other technical factors. Additional multivariate visualization methods such as parallel coordinate plots and scatterplot matrices can reveal patterns and problems not detectable with standard approaches [29].

Impact of QC Failures on Biological Interpretation

The critical importance of rigorous QC becomes evident when examining how specific QC failures lead to incorrect biological interpretations. Several case studies from the literature demonstrate this principle:

In one example, visualization tools detected unexpected patterns in a soybean iron deficiency dataset, where a subset of genes showed consistent differential expression except for one anomalous replicate [29]. Without visualization-based QC, these genes might have been incorrectly designated as differentially expressed or excluded from analysis, when in fact the pattern suggested a biologically meaningful subset of genes with different regulation in that specific replicate.

Spatial transcriptomics studies have revealed that traditional RNA quality metrics like RIN values may not always predict successful outcomes, as even samples with subthreshold quality metrics can yield biologically meaningful data [34]. This highlights the need for platform-specific and application-specific QC thresholds rather than universal standards.

In single-cell RNA-seq, inadequate consideration of QC covariates can lead to unintentional filtering of biologically relevant cell populations. For instance, cells with low counts and/or genes may correspond to quiescent cell populations, and cells with high counts may be larger in size [33]. Applying overly stringent thresholds based on isolated metrics can thus remove legitimate biological variation from the dataset.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for RNA-Seq Quality Control

| Tool | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control of raw sequencing reads | Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq |

| MultiQC | Aggregate multiple QC reports into a single summary | All RNA-seq modalities |

| Trimmomatic/Cutadapt | Read trimming and adapter removal | Bulk RNA-seq |

| STAR | Spliced alignment of RNA-seq reads to genome | Bulk RNA-seq, requires reference genome |

| Salmon/Kallisto | Alignment-free quantification of transcript abundance | Bulk RNA-seq, fast processing of large datasets |

| RNA-SeQC | Comprehensive quality metrics for aligned RNA-seq data | Bulk RNA-seq, post-alignment assessment |

| Cell Ranger | Processing and QC of single-cell RNA-seq data | Single-cell RNA-seq (10x Genomics platform) |

A Practical QC Checklist for Robust RNA-Seq Analysis

Based on the framework presented above, researchers should implement the following minimum checklist to ensure RNA-Seq data quality:

- Pre-sequencing: Verify RNA quality (RIN > 7-8 for bulk RNA-seq), include biological replicates (minimum n=3), and calculate required sequencing depth

- Raw Data: Assess per-base quality scores, adapter content, GC distribution, and sequence duplication levels using FastQC

- Alignment: Evaluate alignment rates, ribosomal RNA content, strand specificity, and genomic feature distribution using RNA-SeQC

- Count Level: Examine sample clustering via PCA, detect outliers using multivariate visualization, and assess normalization effectiveness

- Documentation: Record all QC metrics, filtering thresholds, and any sample exclusions with justifications

Quality control in RNA-seq analysis is not merely a preliminary checklist but an integral, ongoing process that underpins all subsequent biological interpretations. By implementing the comprehensive QC framework outlined in this guide - spanning experimental design, raw read assessment, alignment evaluation, and count-level quality assurance - researchers can safeguard against the "Garbage In, Garbage Out" paradigm that threatens the validity of transcriptomic studies. The tools, metrics, and visualization techniques presented here provide a foundation for detecting technical artifacts before they masquerade as biological discoveries. As RNA-seq technologies continue to evolve and find new applications in both basic research and drug development, maintaining rigorous QC standards will remain essential for extracting meaningful biological insights from increasingly complex datasets.

Practical RNA-seq QC Implementation: Tools, Parameters, and Step-by-Step Protocols

Within the framework of a comprehensive RNA-seq data quality control checklist, the primary analysis phase serves as the critical foundation upon which all subsequent biological interpretations are built. This initial stage transforms raw sequencing data into processed reads ready for alignment and quantification. In the context of a rigorous quality control protocol, primary analysis encompasses the first computational handling of raw base call files, involving demultiplexing, UMI extraction, and adapter trimming. These steps are paramount for ensuring data integrity, as errors introduced at this stage propagate through the entire analytical pipeline, potentially compromising downstream results such as differential expression analysis [2] [35]. The principle of "garbage in, garbage out" is acutely applicable here; even the most sophisticated secondary and tertiary analyses cannot salvage conclusions drawn from fundamentally flawed primary data [2]. This guide details a standardized quality control checklist for the primary analysis workflow, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a methodological approach to validate these essential first steps in their RNA-seq experiments.

The primary analysis of RNA-seq data functions as a specialized data refinement pipeline, converting raw sequencer output into clean, sample-specific sequence reads. This process is typically segmented into three core operations:

Demultiplexing: This is the process of sorting sequenced reads from a multiplexed pool into individual sample-specific files based on their unique index (barcode) sequences. During library preparation, individual samples are tagged with short, known DNA barcodes, allowing multiple samples to be pooled and sequenced simultaneously in a single lane. Demultiplexing bioinformatically reverses this pooling, assigning each read to its sample of origin by recognizing its index sequence [2] [35]. Sophisticated index designs, such as Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs), allow for the detection and correction of index hopping errors, thereby salvaging reads that might otherwise be lost and maximizing data yield [2].

UMI Extraction: When a protocol utilizes Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), these short random nucleotide sequences must be identified and removed from the read sequence. UMIs are incorporated during library preparation to label individual RNA molecules uniquely before PCR amplification. Bioinformatically, the UMI sequence is "spliced out" from the body of the sequencing read and added to the read's header in the FASTQ file. This preserves the molecular identity for downstream PCR duplicate removal without interfering with the alignment of the read to the reference genome [2] [30]. Failure to extract UMIs can significantly reduce alignment rates due to introduced mismatches [2].

Adapter Trimming: This step involves the removal of artificial adapter sequences and low-quality bases from the ends of sequencing reads. Adapters are necessary for the sequencing process but are not part of the biological sample. If not removed, they can interfere with alignment and lead to false mappings. Trimming also removes low-quality base calls, often found at the ends of reads, and other artifacts such as poly(A) tails or poly(G) sequences that can arise from specific sequencing chemistries [2] [36] [37].

The logical sequence and data flow between these operations, from the raw BCL files to the trimmed FASTQ files ready for secondary analysis, are visualized in the workflow diagram below.

Detailed Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Demultiplexing: From BCL to Sample-Specific FASTQ Files

The demultiplexing process begins with the raw data output from Illumina sequencers, which is stored in binary base call (BCL) format. The primary tool for converting these files into the standard FASTQ format while performing demultiplexing is Illumina's bcl2fastq software. This software identifies the index sequences associated with each read and sorts the reads into separate FASTQ files based on these indices [2] [35].

Detailed Protocol:

- Input: Raw BCL files from the sequencing run.

- Software Execution: Run

bcl2fastq, specifying the input directory containing the BCL files and the output directory for the resulting FASTQ files. It is crucial to enable index error correction if using a dual-indexing strategy, as this can rescue a significant portion of reads that would otherwise be discarded due to minor errors in the index sequence. - Output: For a single-read run, one FASTQ file per sample is generated. For a paired-end run, two FASTQ files per sample are created (R1 and R2) [2].

- Alternative Tools: While

bcl2fastqis the standard, alternative tools like Lexogen's iDemux are available. iDemux is particularly useful for complex library designs, such as triple-indexed Quantseq-Pool libraries, as it can simultaneously demultiplex and perform error correction on all indices, maximizing data recovery [2].

UMI Extraction: Capturing Molecular Identity

UMI extraction is performed on the demultiplexed FASTQ files. The goal is to remove the UMI sequence from the read body and record it in the read header without altering the core transcript-derived sequence. This is typically accomplished using tools like UMI-tools [38].

Detailed Protocol using UMI-tools:

- Input: Demultiplexed FASTQ file(s).

- Pattern Specification: The UMI location and structure must be defined using a specific pattern or a regular expression (regex). For example, if a 12-base UMI is located immediately after a constant adapter sequence, the regex pattern would be designed to:

- Match and discard the constant adapter

(?P<discard_1>AACTGTAGGCACCATCAAT). - Capture the next 12 random bases as the UMI

(?P<umi_1>.{12}). - Match and discard any remaining adapter or primer sequence

(?P<discard_2>AGATCGGAAGAGCACACGTCT.+)[38].

- Match and discard the constant adapter

- Software Execution: The

umi_tools extractcommand is run with the--extract-method=regexand the defined--bc-pattern. The tool processes each read, applies the regex, and creates a new FASTQ file where the UMI is moved to the header. - Output: A new FASTQ file where read headers contain the UMI sequence (e.g.,

_UMI:ACGTACGTACGT), and the read sequences themselves have the UMI and specified adapter sequences removed [2] [38].

Adapter and Quality Trimming: Polishing the Reads

Trimming is the final cleansing step in primary analysis. It removes adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and other artifacts. Common tools for this task include Trimmomatic, Cutadapt, and fastp [2] [36] [37].

Detailed Protocol using Trimmomatic:

- Input: UMI-extracted FASTQ files (or demultiplexed files if UMIs are not used).

- Parameter Setting:

- Adapter Clipping: Provide a file containing the adapter sequences (

ILLUMINACLIP:TruSeq3-PE.fa:2:30:10). - Quality Trimming: Set thresholds for leading and trailing low-quality bases (

LEADING:3,TRAILING:3). - Minimum Read Length: Define a minimum length for reads to be retained after trimming (

MINLEN:36) [39].

- Adapter Clipping: Provide a file containing the adapter sequences (

- Software Execution: Execute Trimmomatic in Java. For paired-end reads, it will produce four output files: two for pairs where both reads passed trimming, and two for singleton reads where only one read of a pair passed.

- Quality Verification: It is considered best practice to run a quality control tool like

FastQCon the trimmed FASTQ files to confirm the successful removal of adapters and the improvement in per-base sequence quality [39].

Table 1: Common Trimming Tools and Their Characteristics

| Tool | Key Features | Typical Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Trimmomatic [36] [39] | Handles paired-end data, multiple trimming steps. | Standard, robust trimming for both single and paired-end RNA-seq. |

| Cutadapt [2] [36] | Excels at precise adapter removal. | Ideal when the primary concern is specific adapter contamination. |

| fastp [36] [37] | Very fast, all-in-one processing with integrated QC. | High-throughput environments or when rapid processing is a priority. |

| Trim Galore [37] | Wrapper for Cutadapt and FastQC, automated. | User-friendly option that simplifies the trimming and QC workflow. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The wet-lab reagents and computational tools selected during library preparation and primary analysis directly determine the options and efficiency of the bioinformatic workflow.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions and Their Functions in Primary Analysis

| Item / Reagent | Function in Primary Analysis |

|---|---|

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) [2] | Enables high-fidelity demultiplexing and correction of index hopping errors, maximizing usable data yield. |

| UMI-containing Library Prep Kits [2] [30] | Incorporates Unique Molecular Identifiers into cDNA fragments, allowing for bioinformatic correction of PCR amplification bias. |

| Direct RNA Sequencing Kit (SQK-RNA004) [6] | Allows for sequencing of native RNA without cDNA synthesis, bypassing reverse transcription biases but requires higher input RNA (e.g., 300 ng poly(A) RNA). |

| bcl2fastq / iDemux Software [2] | Performs the core demultiplexing function, converting raw BCL files into sample-specific FASTQ files. |

| UMI-tools [38] | A specialized software package for UMI extraction, error correction, and deduplication. |

| Trimmomatic / Cutadapt [2] [36] [39] | Standard tools for removing adapter sequences and trimming low-quality bases from reads. |

Quality Control Metrics and Validation

A robust primary analysis is verified through specific quality metrics. The following table outlines key checkpoints and their acceptable thresholds, serving as a practical checklist for researchers.

Table 3: Quality Control Metrics for Primary Analysis Steps

| Analysis Step | QC Metric | Target / Acceptable Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Run [2] [35] | % Bases ≥ Q30 | > 80% | Indicates high base-calling accuracy (99.9%). |

| Sequencing Run [2] [35] | Cluster Density | Within instrument spec (e.g., 129-165 k/mm² for NextSeq) | Over- or under-clustering can reduce data quality. |

| Demultiplexing [2] | Index Assignment Rate | High percentage with low % of unknown indices. | Low rates may indicate index hopping or poor quality libraries. |

| Adapter Trimming [39] | Adapter Content (post-trimming) | Near 0% | Confirms successful removal of adapter sequences. |

| Read Trimming [39] | Per-base Sequence Quality | All positions in green/orange quality zone. | Ensures low-quality bases have been trimmed, improving mappability. |

| Data Retention | % Reads Remaining After Trimming | High retention rate (e.g., >90%) | Indicates that trimming was not overly aggressive, preserving most of the data. |

The primary analysis workflow—demultiplexing, UMI extraction, and adapter trimming—constitutes the non-negotiable foundation of a rigorous RNA-seq quality control protocol. By meticulously executing these steps and verifying their success using the outlined metrics and checklists, researchers can ensure that their data is accurate, reproducible, and fit for purpose. A carefully controlled primary analysis process mitigates technical artifacts and sets the stage for reliable secondary and tertiary analyses, ultimately leading to more confident biological discoveries and supporting the robust evidence required in drug development and clinical research.

Within the broader context of RNA-seq data quality control checklist research, the selection of preprocessing tools represents a foundational decision that significantly influences all subsequent analytical outcomes. Read trimming serves as the essential first step in RNA-seq data analysis, where sequencing artifacts such as adapter sequences, low-quality bases, and contaminating sequences are removed to ensure the accuracy of downstream interpretation. Failure to adequately perform this quality control step can introduce substantial biases in alignment rates, quantification accuracy, and differential expression testing, potentially compromising the biological validity of study conclusions [40] [2] [1].

The landscape of trimming tools has evolved substantially, with Cutadapt, Trimmomatic, and fastp emerging as three widely utilized options. Each tool employs distinct algorithmic approaches and offers unique feature sets, leading to measurable differences in processing speed, computational efficiency, and output quality. Recent benchmarking studies have demonstrated that tool selection can significantly impact downstream results, including variant calling accuracy and HLA typing reliability [41]. This technical guide provides a comprehensive, evidence-based comparison of these three tools, enabling researchers to make informed selections aligned with their specific experimental designs and analytical requirements within the RNA-seq quality control framework.

Individual Tool Profiles