Validating Predicted Membrane Protein Structures: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

The rapid advancement of AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold has democratized access to membrane protein models, yet their validation remains a critical challenge.

Validating Predicted Membrane Protein Structures: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

The rapid advancement of AI-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold has democratized access to membrane protein models, yet their validation remains a critical challenge. This article provides a comprehensive framework for researchers and drug development professionals to rigorously assess the accuracy and reliability of these predicted structures. We explore the foundational principles of membrane protein biology, detail cutting-edge experimental and computational validation methodologies, address common pitfalls in the analysis of dynamic protein-lipid interactions and multi-chain complexes, and present comparative benchmarks for binding site prediction tools. By synthesizing current best practices and emerging trends, this guide aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to confidently leverage predicted structures for accelerating drug discovery and mechanistic studies.

The Why and How: Fundamental Challenges in Membrane Protein Structural Biology

The validation of computationally predicted membrane protein structures represents a critical frontier in structural biology and drug development. Despite comprising approximately 30% of the protein-coding genes in organisms and holding immense significance as therapeutic targets, membrane proteins remain notoriously challenging to study experimentally [1] [2]. The inherent hydrophobicity of their transmembrane domains, low natural abundance, and instability outside their native lipid bilayers present a series of unique obstacles from expression to structural determination. This application note details the major technical challenges and provides validated protocols designed to overcome these hurdles, enabling researchers to bridge the gap between computational prediction and experimental validation.

Key Challenges in Membrane Protein Research

The path to a high-resolution membrane protein structure is iterative, and success at each stage depends heavily on the preparation of a pure, homogeneous, and stable protein sample [3]. The major bottlenecks are summarized below.

Expression and Solubilization

Heterologous expression of membrane proteins often fails because the host system (e.g., E. coli) may lack the necessary folding machinery or specific lipid environment [3]. Following expression, extracting the protein from the membrane with detergents is a critical first step, but identifying the right detergent is empirical and can make or break subsequent experiments [3].

Purification and Stability

Once solubilized, membrane proteins are prone to aggregation and loss of function. Maintaining stability throughout purification requires the protein to remain in a discrete fold and oligomeric state. A useful benchmark for a sample suitable for crystallization is >98% purity, >95% homogeneity, and >95% stability when stored concentrated at 4°C for one week [3].

Structural Determination

The most prevalent methods for studying membrane proteins involve detergents that strip away the vital native membrane context, which can impede the study of native conformational states and protein-lipid interactions [4]. Recent advances in native nanodisc-forming polymers aim to preserve this local environment, but their application has been constrained by low extraction efficiencies compared to detergents [4].

Quantitative Assessment of Methodologies

Performance of All-Atom Physical Models for Prediction

Computational models are vital for guiding experimental work. The table below summarizes the performance of an all-atom physical model in recapitulating native membrane protein structures.

Table 1: Performance metrics of an all-atom physical model for membrane protein prediction and design.

| Test Type | Description | Success Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Side-chain Conformation Recovery | Prediction of correct chi1 and chi2 dihedral angles on fixed protein backbones. | 73% at buried positions [1] |

| Amino Acid Recovery | Selection of native amino acids in computational redesign experiments. | 34% of all positions; 43% of buried positions [1] |

| Native TM Helix Docking | Discrimination of native helical interfaces from non-native decoys. | Significant energy gaps (Z score >1) for most complexes [1] |

| De novo Structure Prediction | Prediction of structures for small membrane protein domains (<150 residues). | Near-atomic accuracy (<2.5 Å) [1] |

Efficiency of Membrane Protein Extraction Methods

The choice of extraction method fundamentally shapes downstream experiments. The following table compares different solubilization agents.

Table 2: Comparison of membrane protein solubilization and stabilization methods.

| Method | Key Feature | Proteome-wide Extraction Efficiency | Best Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| Conventional Detergents | Strips native lipid environment [4] | Variable, often high for abundant proteins [4] | Initial solubilization screening; crystallization [3] |

| Native Nanodisc Polymers (MAPs) | Preserves native lipid environment [4] | Database available for 2,065 unique MPs across 11 polymers [4] | Studying native conformation & protein-lipid interactions [4] |

| Proteome-Wide MAP Screening | Data-driven selection of optimal polymer | Enables extraction efficiency surpassing detergents [4] | Targeting low-abundance MPs or specific multi-protein complexes [4] |

Recommended Protocols

Protocol 1: Screening for Optimal Detergent Solubilization

This protocol is adapted from a general method for membrane protein crystallization [3].

Reagents Needed:

- Purified membrane fraction

- Detergent stock solutions (e.g., n-Octyl-β-D-glucoside (OG), n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM), Laurydimethylamine-oxide (LDAO), CHAPS, Fos-Choline-12 (FC-12))

- SDS-PAGE and Western Blot equipment

- Anti-His antibody (or other tag-specific antibody)

Procedure:

- Prepare Membranes: Thaw frozen membranes on ice. All subsequent steps should be performed on ice or at 4°C.

- Determine Membrane Concentration: Perform a serial dilution of the resuspended membrane and analyze by Western blot to identify the most dilute sample that produces a signal. Dilute the stock membranes to a concentration eight times higher than this limit.

- Solubilize: Aliquot 150 µL of diluted membrane into ultracentrifuge tubes. Add 150 µL of different solubilization buffers, each containing a unique detergent.

- Mix Gently: To avoid foam, mix by gentle pipetting. Add a small magnetic stir bar and agitate for 12-18 hours at 4°C.

- Separate and Analyze: Centrifuge the mixtures at 100,000g for 30 minutes at 4°C to pellet unsolubilized material.

- Evaluate Efficiency: Take samples of the initial mixture, the pellet, and the supernatant. Analyze by Western blot. A successful detergent will show the target protein predominantly in the supernatant.

Protocol 2: Spatially Resolved Extraction using Membrane-Active Polymers (MAPs)

This protocol leverages a high-throughput, proteome-wide platform for efficient extraction into native nanodiscs [4].

Reagents Needed:

- Library of Membrane-Active Polymers (MAPs)

- Target cells or isolated organellar membranes

- Fluorescent lipid (e.g., for quenching assay)

- Sodium dithionite solution

- NeutrAvidin Agarose (or other affinity resin)

Procedure:

- Benchmark MAPs (Bulk Solubilization Assay):

- Label native cell membranes with a fluorescent lipid.

- Incubate the labeled membranes with the target MAP.

- Take an initial fluorescence reading (fl1).

- Quench the sample with sodium dithionite, which quenches fluorescence only in the outer leaflet of vesicles and both leaflets of nanodiscs.

- Take a second fluorescence reading (fl2).

- Calculate the percentage of membrane solubilized into true nanodiscs using the formula:

Bulk Solubilization = 100 - [ (2 × fl2) / fl1 × 100 ][4].

- Extract and Purify:

- Consult a proteome-wide database to identify the optimal MAP for your target protein [4].

- Incubate the cellular membranes with the selected MAP to form native nanodiscs.

- Purify the target MP-containing nanodiscs using affinity chromatography (e.g., if the MP is His-tagged) or size-exclusion chromatography.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key reagents for membrane protein extraction, purification, and analysis.

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|

| n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltoside (DDM) | Mild Detergent | Solubilizes proteins by mimicking lipid environment | Initial extraction and purification [3] |

| Styrene-Maleic Acid (SMA) Copolymer | Membrane-Active Polymer (MAP) | Forms native nanodiscs (SMALPs) that preserve lipid bilayer | Studying proteins in near-native state [4] |

| Mass Photometry | Bioanalytical Instrument | Measures mass distribution of samples at single-molecule level | Assessing sample purity, oligomeric state, and complex formation [5] |

| Proteome-Wide MAP Database | Computational Resource | Guides selection of optimal polymer for a target MP | Enabling high-efficiency extraction of low-abundance targets [4] |

| Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) | Purification Technique | Separates proteins/nanodiscs by size and shape | Final polishing step to obtain a monodisperse sample [4] |

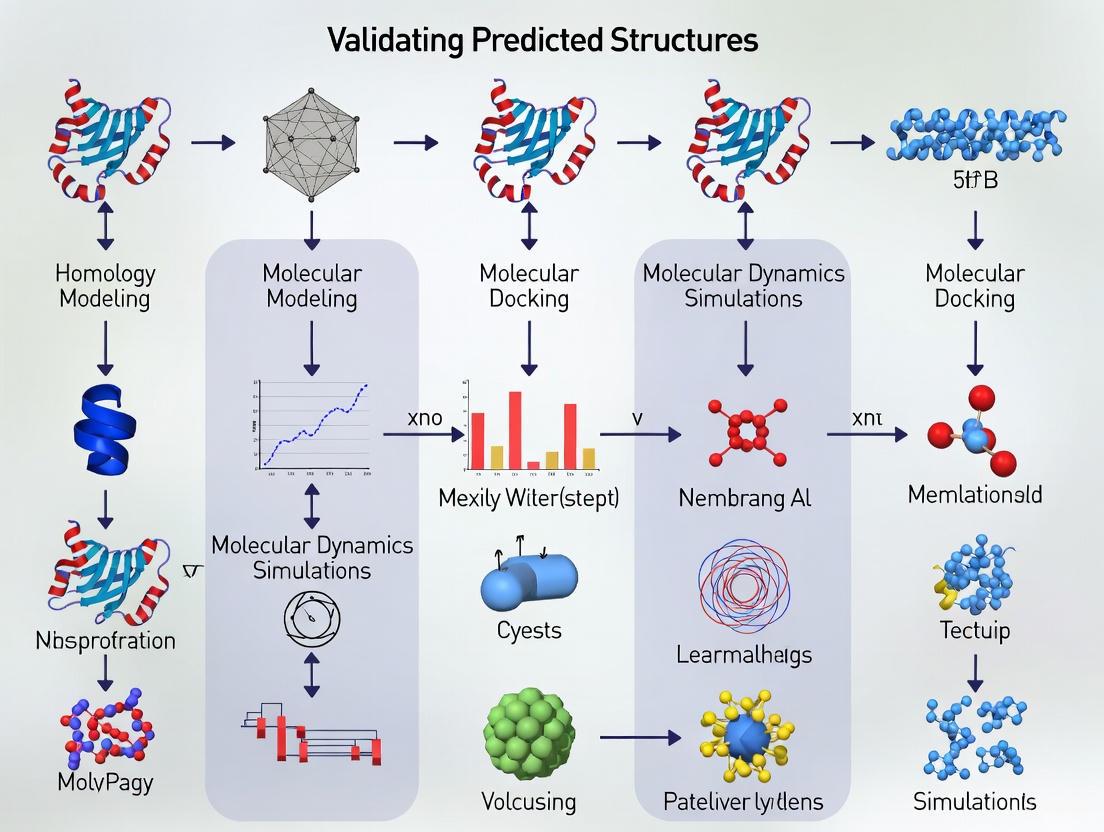

Workflow Visualization

The Path to a Membrane Protein Structure

The following diagram outlines the general iterative workflow for membrane protein structural determination, highlighting key decision points and the role of validation.

Native Nanodisc Extraction Platform

This diagram illustrates the modern approach for extracting membrane proteins with their native lipid environment using membrane-active polymers.

Application Note: Validating AI-Predicted Membrane Protein Structures

The prediction of membrane protein structures has been revolutionized by artificial intelligence (AI), particularly through deep learning models like AlphaFold. However, the inherent limitations of these AI models necessitate rigorous experimental validation to confirm the biological relevance of predicted structures, especially for dynamic conformational states crucial for function. This document outlines standardized protocols and resources for the computational and experimental validation of AI-predicted membrane protein structures, providing a critical framework for researchers in structural biology and drug development.

Key Computational Tools and Prediction Methods

AI-driven structure prediction can be broadly categorized into two complementary approaches. The following table summarizes the core methodologies.

Table 1: Computational Approaches for Membrane Protein Structure Prediction

| Method Category | Key Principle | Example Tool(s) | Primary Input | Key Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Co-evolution Analysis | Infers structural contacts from evolutionary covariation in multiple sequence alignments (MSAs). | EVfold [6] | Diverse MSA | De novo 3D coordinates, contact maps |

| Deep Learning (End-to-End) | Uses deep neural networks to predict atomic coordinates from sequence and MSA information. | AlphaFold2, RoseTTAFold [7] | Sequence & MSA | Atomic-level 3D model (with confidence metrics) |

| Generative Models | Models conformational diversity through iterative denoising or flow matching. | Diffusion/Flow Matching Models [7] | Single Sequence or MSA | Ensemble of diverse predicted conformations |

While AlphaFold2 has demonstrated remarkable accuracy for static, monomeric protein folds, its predictions represent a single, ground-state conformation [7]. Methods like EVfold and generative models are crucial for exploring the conformational landscape, a key aspect for understanding the function of dynamic membrane proteins like GPCRs and transporters [6] [7].

Experimental Validation Protocols

Computational predictions are hypotheses that require experimental verification. The following protocols detail foundational methods for topology determination and conformational analysis.

Protocol: Topology Mapping Using Reporter Gene Fusion

This molecular biology technique determines the transmembrane topology of a protein by fusing reporter proteins (e.g., green fluorescent protein, GFP) to different domains of the target membrane protein [2].

- Design of Fusion Constructs: Create a series of expression plasmids where a reporter gene (e.g., gfp) is inserted in-frame at various positions throughout the gene of interest. Positions should target putative cytoplasmic and extra-cytoplasmic loops based on the AI prediction.

- Heterologous Expression: Transfect the fusion constructs into an appropriate cell line (e.g., HEK293) or express them in a cell-free system.

- Fluorescence Detection and Analysis:

- For intact cells, use fluorescence microscopy to determine the localization of the signal.

- A fluorescent signal inside the cell indicates a cytoplasmic reporter.

- A fluorescent signal outside the cell (or within organelles) indicates an extra-cytoplasmic reporter.

- Topology Model Building: Compile the results from all fusion constructs to build a experimentally determined topology map, which can be compared directly to the AI-predicted model.

Protocol: Assessing Dynamics via Hydrogen-Deuterium Exchange Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS)

HDX-MS measures the rate at of protein backbone amide hydrogens with deuterium from the solvent, providing insights into protein dynamics, solvent accessibility, and conformational changes [7].

- Sample Preparation: Purify the target membrane protein in a suitable detergent or membrane mimetic.

- Deuterium Labeling:

- Dilute the protein into a deuterated buffer for a series of time points (e.g., 10 seconds to 2 hours).

- Quench the reaction by lowering pH and temperature to minimize back-exchange.

- Proteolysis and LC-MS/MS Analysis:

- Pass the quenched sample through an immobilized protease column for rapid digestion.

- Analyze the resulting peptides using liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry.

- Data Processing:

- Identify peptides from MS/MS data.

- Measure the mass increase of each peptide over time due to deuterium incorporation.

- Interpretation:

- Regions with slow deuterium uptake are typically structured or involved in hydrogen bonding.

- Regions with fast uptake are flexible or solvent-exposed.

- Compare deuterium uptake patterns of the protein in different states (e.g., apo vs. ligand-bound) to identify conformational changes and validate predicted dynamic states.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Databases

Successful validation relies on high-quality data and specialized reagents.

Table 2: Key Resources for Membrane Protein Research

| Resource Name | Type | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| GPCRmd | Molecular Dynamics Database | Provides curated MD simulation trajectories for G Protein-Coupled Receptors to study dynamics and mechanism [7]. |

| MemProtMD | Molecular Dynamics Database | Automated MD simulations of membrane proteins embedded in a lipid bilayer, providing data on folding and stability [7]. |

| ATLAS | Molecular Dynamics Database | A large-scale database of MD simulations for general proteins, useful for benchmarking and analysis [7]. |

| Detergent Screening Kits | Research Reagent | Kits containing various detergents for solubilizing and stabilizing membrane proteins during purification. |

| Lipid Nanodiscs | Research Reagent | Membrane mimetics that provide a more native-like lipid environment for studying membrane proteins compared to detergents. |

| BacMam System | Expression Tool | A baculovirus-based system for efficient transduction and high-level protein expression in mammalian cells, ideal for difficult membrane proteins. |

Workflow Visualization: From AI Prediction to Experimental Validation

The following diagram outlines the integrated computational and experimental workflow for validating AI-predicted membrane protein structures.

Integrated AI and Experimental Validation Workflow

Inherent Limitations and Future Directions

Despite their power, AI models face inherent limitations. A primary challenge is the reliance on large, diverse multiple sequence alignments for accurate prediction; families with poor sequence representation remain difficult to model [6]. Furthermore, capturing the full spectrum of functionally relevant conformational states and the effects of the native lipid environment is an ongoing frontier [7]. The future of the field lies in integrating AI predictions with experimental data from HDX-MS and cryo-EM into hybrid modeling approaches and developing next-generation generative models that can more accurately predict dynamic conformational ensembles [7].

The field of membrane protein structural biology is undergoing a revolution, driven by groundbreaking advances in artificial intelligence (AI) for protein structure prediction. Tools like AlphaFold 2 have made it possible to generate high-quality structural models directly from amino acid sequences, bypassing traditionally laborious and costly experimental methods [8] [9]. These models provide invaluable hypotheses for understanding the molecular mechanisms of solute transport and have accelerated drug discovery pipelines [10]. However, within the context of membrane protein research, a critical caveat must be emphasized: predicted models are not ground truth. They are computational inferences that, while powerful, possess inherent limitations. This application note details the reasons for these limitations and provides structured protocols for the experimental validation essential to confirm the functional reality of predicted membrane protein structures.

The Inherent Limitations of Predicted Models

The remarkable accuracy of AI-based structure prediction is built upon learning from the vast repository of experimentally determined structures in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) [9]. Despite this, several fundamental challenges prevent these models from fully capturing the biological reality of membrane proteins.

Table 1: Key Limitations of AI-Predicted Membrane Protein Structures

| Limitation | Underlying Cause | Impact on Model Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Static Representation | Models output a single, static conformation [11]. | Fails to capture the dynamic conformational changes essential for transporter function [8] [11]. |

| Membrane Environment | Models do not accurately represent the native lipid bilayer or lipid-protein interactions [8]. | Critical for stability and function; its absence can lead to distorted folds or missed allosteric sites [8]. |

| Ligand & Cofactor Binding | Predicting details of ligand binding, protein-lipid interactions, and oligomeric states remains challenging [8] [11]. | Models may lack bound substrates, ions, or drugs, providing an incomplete picture of the functional site. |

| Intrinsically Disordered Regions | Flexible regions without a fixed structure are poorly defined [11]. | These regions are often functionally significant, and their absence creates an incomplete structural picture. |

| Dependency on Training Data | Accuracy is higher for protein families well-represented in the PDB [6] [9]. | Models for novel folds or proteins with few homologs may be less reliable. |

A core epistemological challenge is the Levinthal paradox, which highlights the astronomical number of conformations a protein could theoretically adopt. While AI models shortcut this random search, they still struggle to represent the vast conformational ensemble that a protein samples in its native state [11]. Furthermore, the membrane environment is not a passive backdrop; it actively participates in folding, stability, and function. The hydrophobic and structural flexibility of membrane proteins, essential for their biological roles, makes them particularly challenging to study and predict [8]. While AI models are valuable as initial hypotheses, they cannot predict protein function by themselves [8].

Diagram 1: AI model limitations create a knowledge gap.

Experimental Validation Workflow

A multi-technique approach is required to bridge the gap between a predicted model and a validated structure. The following workflow provides a robust framework for confirmation.

Diagram 2: Multi-step validation workflow.

Protocol 2.1: Validating Transmembrane Topology Using Cys-Scanning Mutagenesis

Purpose: To experimentally determine the membrane-embedded regions and overall topology of a predicted helical membrane protein, confirming the locations of its extracellular and intracellular loops.

Principle: Cysteine residues introduced via mutagenesis are reacted with membrane-impermeable biotinylated maleimide reagents. Biotinylation is detected only on cysteine residues accessible from the aqueous phase (loops), not those buried in the membrane [8].

Materials: Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Topology Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Cys-less Template | A functional mutant of the target protein with all native cysteine residues removed. | Serves as a clean background for introducing single Cys mutations [8]. |

| Membrane-Impermeable Biotinylation Reagent | Labels solvent-accessible cysteine residues. | Polyethylene glycol-maleimide-biotin (e.g., Male-PEG11-Biotin). Its size ensures membrane impermeability. |

| Streptavidin Conjugates | For detection of biotinylated proteins. | Streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase (HRP) for Western blotting. |

| Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins for analysis. | Use mild, non-denaturing detergents (e.g., DDM, UDM) to preserve native structure [8]. |

Procedure:

- In Silico Design: Using the predicted model, identify residues in putative transmembrane helices and loops. Design a series of single-point mutants, each introducing a cysteine at a unique position throughout the protein sequence.

- Expression and Purification: Express the Cys-less template and each single Cys mutant in an appropriate host system (e.g., E. coli, HEK293 cells). Purify the proteins using affinity chromatography in the presence of a mild detergent like DDM.

- Biotinylation Reaction:

- Incubate 10 µg of each purified protein with a 10-fold molar excess of Male-PEG11-Biotin on ice for 30 minutes.

- Include a control sample for each mutant where the reaction is quenched with 10 mM DTT before adding the biotinylation reagent.

- Detection and Analysis:

- Terminate the reaction by adding DTT.

- Separate the proteins by SDS-PAGE and transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane.

- Perform a Western blot probed with Streptavidin-HRP to detect biotinylated proteins.

- Re-probe the same blot with an antibody against the protein itself to confirm equal loading.

- Interpretation: A strong biotinylation signal indicates the cysteine residue is located in a solvent-accessible loop. Weak or absent signal suggests the residue is buried within the membrane bilayer or the protein core. The resulting pattern of accessibility should be compared directly with the AI-predicted topology.

Protocol 2.2: Functional Corroboration Using Site-Directed Mutagenesis

Purpose: To test the functional implications of a predicted active or binding site, thereby providing evidence for the model's biological relevance.

Principle: If a model predicts that specific residues form a substrate-binding pocket, then targeted mutation of those residues should disrupt function without destabilizing the overall protein fold [8] [10].

Procedure:

- Residue Selection: Based on the predicted model, select 3-5 residues postulated to be critical for substrate binding or transport.

- Mutant Generation: Generate point mutants for each selected residue, typically substituting them with alanine (Ala-scanning) or a residue with opposite properties (e.g., charged to uncharged).

- Functional Assay:

- Express and purify the wild-type and mutant proteins.

- Measure transport activity using a radiolabeled or fluorescent substrate in a reconstituted proteoliposome assay.

- Determine kinetic parameters (Km, Vmax) for the wild-type and each mutant.

- Stability Check: Ensure that the mutations do not globally destabilize the protein by using methods like circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy to confirm secondary structure integrity or size-exclusion chromatography to check for aggregation.

- Interpretation: A mutant that retains a wild-type-like structural fold but exhibits a significant reduction (e.g., >80%) or complete loss of transport activity provides strong evidence that the targeted residue is functionally important, thereby corroborating the predicted model.

Integrating Computational and Experimental Data

The ultimate goal is a synergistic cycle where predictions guide experiments, and experimental results, in turn, refine computational models. Techniques like cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) can provide near-atomic resolution structures that serve as a definitive benchmark for a predicted model [8]. Furthermore, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations can be used to breathe life into a static model, exploring conformational flexibility and lipid interactions around the scaffold provided by the prediction [11].

Future directions will focus on determining structures within native membrane environments using cryo-electron tomography (CryoET) and generating experimental data on dynamics and interactions to train the next generation of machine-learning algorithms, ultimately leading to more predictive and physiologically accurate models [8] [11].

AI-predicted models of membrane proteins are powerful starting points that have dramatically accelerated structural biology. However, they are hypotheses, not definitive answers. Their static nature and inability to fully capture the complexities of the membrane environment necessitate rigorous experimental validation. By employing the detailed protocols and frameworks outlined in this application note—from topology mapping to functional assays—researchers can confidently bridge the gap between computational prediction and biological ground truth, ensuring that drug discovery and mechanistic studies are built upon a solid structural foundation.

{ article }

The Critical Role of the Lipid Bilayer in Native Structure and Function

Application Notes & Protocols for the Validation of Predicted Membrane Protein Structures

Membrane proteins constitute over 30% of the human proteome and are the targets of more than 60% of pharmaceuticals [12]. Their native structure and function are inextricably linked to their environment: the lipid bilayer. This phospholipid bilayer is not merely a passive scaffold; it is a complex, anisotropic solvent that imposes precise physicochemical constraints. The hydrophobic effect drives the spontaneous assembly of amphipathic lipid molecules into a bilayer typically 3-4 nm thick, creating a barrier that is impermeable to most hydrophilic molecules [13] [14]. For researchers focused on validating computationally predicted membrane protein structures—such as those generated by AlphaFold2—ignoring the bilayer context risks severe misinterpretation. A model may be stereochemically sound yet functionally meaningless if its hydrophobic segments are exposed to water or its interfacial residues are mispositioned relative to the lipid environment. These application notes provide a structured framework and practical tools for incorporating the lipid bilayer into the experimental validation pipeline, ensuring that predicted structures are evaluated against biologically relevant criteria.

Quantitative Characterization of the Bilayer Environment

The lipid bilayer exhibits distinct physicochemical gradients along the axis normal to its plane. Successfully validating a membrane protein structure requires quantitative knowledge of these gradients and how they influence protein topology, amino acid preference, and ligand binding.

Key Physicochemical Gradients of the Lipid Bilayer

The table below summarizes the critical properties that vary with depth in the bilayer, influencing protein structure and ligand binding.

Table 1: Key Gradients Across the Lipid Bilayer and Their Biochemical Implications

| Bilayer Region | Approximate Depth | Water Density | Dielectric Constant (Polarity) | Key Properties & Influences |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrated Headgroup | 0.8 - 0.9 nm from core [13] | High (~2M) [13] | Higher (More Polar) | Contains phosphate groups; site of electrostatic and hydrogen-bonding interactions [13]. |

| Intermediate/Interface | ~0.3 nm thick [13] | Partial (Rapidly Dropping) [13] | Intermediate | Rich in glycerol backbone and ester linkages; favored location for aromatic side chains (e.g., Tryptophan) and cholesterol [13] [14]. |

| Hydrophobic Core | 3 - 4 nm thick [13] | Nearly Zero [13] | Low (Hydrophobic) | Hydrocarbon tail region; favors saturated hydrophobic residues; critical for hydrophobic matching [13] [15]. |

Impact on Protein and Ligand Properties

The bilayer's anisotropy directly dictates the preferred location of amino acids and small molecules. Analysis of curated databases, such as the Lipid-Interacting LigAnd Complexes Database (LILAC-DB), reveals that ligands binding at the protein-lipid interface are chemically distinct, possessing higher lipophilicity (clogP), molecular weight, and a greater number of halogen atoms compared to ligands for soluble proteins [16]. Furthermore, the atomic properties of these ligands vary significantly depending on their depth and exposure to the bilayer [16]. This also applies to protein sequences; membrane-spanning segments exhibit a distinct amino acid composition compared to soluble domains, which is a critical feature for identifying transmembrane regions and validating structural predictions [16].

Experimental Protocols for Functional Validation in a Bilayer Context

Computational models require experimental verification under conditions that mimic the native membrane environment. The following protocols are essential for this functional validation.

Protocol 1: Formation of Asymmetric Contact Bubble Bilayers (CBBs) for Electrophysiology

The CBB method combines the lipid composition control of planar bilayers with the low electrical noise of patch-clamp recordings, enabling high-resolution functional studies of ion channels [17].

Key Research Reagents:

- Pure or Mixed Lipids: To mimic the cytoplasmic or extracellular leaflet (e.g., DPPC, DOPE, DOPS). Function: Form the structural basis of the bilayer and define its physicochemical properties [17] [18].

- Hexadecane: Function: Organic solvent phase into which the aqueous bubbles are blown; it accommodates the lipid monolayers [17].

- Electrolyte Solution: Function: Conducts ionic current for electrophysiological recording.

- Channel-Reconstituted Liposomes: Function: Serve as a delivery system to incorporate the protein of interest into the pre-formed bilayer [17].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Procedure:

- Bubble Formation: Fill glass patch-clamp pipettes with an electrolyte solution containing liposomes of the desired lipid composition. Blow a bubble of this solution into the hexadecane bath and maintain positive pressure to stabilize the bubble size [17].

- Monolayer Formation: The lipids from the liposomes spontaneously form a stable monolayer at the bubble-hexadecane interface [17].

- Bilayer Docking: Bring two such monolayer-lined bubbles into contact. Upon docking, the two monolayers reassemble into a stable planar lipid bilayer separating the two aqueous compartments inside the bubbles [17].

- Protein Incorporation: Introduce liposomes containing the reconstituted membrane protein (e.g., ion channel) into one of the bubbles. The proteins will incorporate into the newly formed bilayer [17].

- Functional Assay: Perform single-channel current recordings with a high signal-to-noise ratio. The system allows for perfusion of the bath to change the lipid environment or application of suction to manipulate bilayer mechanics [17].

Protocol 2: Quantifying Membrane-Protein Binding with Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS)

FCS is a powerful technique for quantifying the reversible binding of proteins to membranes, described here for use with lipid vesicles [19].

Key Research Reagents:

- Fluorescently-Labeled Protein: The target protein (e.g., an antibody or peripheral membrane protein) must be labeled with a bright, photostable fluorophore. Function: Enables detection and fluctuation analysis via FCS.

- Lipid Vesicles (LUVs/SUVs): Large or small unilamellar vesicles of a defined lipid composition. Function: Serve as membrane models for binding studies [18].

- Dialysis System or Size-Exclusion Columns: Function: For buffer exchange to separate unbound protein or to change the external solution composition after vesicle preparation [18].

Workflow Diagram:

Detailed Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Incubate the fluorescently-labeled protein with lipid vesicles at various lipid concentrations to titrate the binding. Allow the system to reach a reversible equilibrium where proteins are constantly associating and dissociating from the vesicles [19].

- FCS Measurement: Focus a laser beam into a very small observation volume (~1 fL) within the sample. Record the intensity fluctuations of the fluorescent signal as labeled proteins diffuse in and out of the volume. Free proteins diffuse rapidly, while vesicle-bound proteins diffuse much more slowly [19].

- Data Analysis: Fit the experimentally obtained autocorrelation function using a newly derived theoretical model that explicitly accounts for reversible protein-membrane dissociation and reassociation to the same or a different vesicle. This model overcomes the limitations of previous analyses that assumed non-reversible binding [19].

- Parameter Extraction: From the fit, accurately determine the partition coefficient (Kₓ), which quantifies the equilibrium distribution of the protein between the membrane and aqueous phases. The methodology also establishes the confidence bounds for the retrieved Kₓ [19].

- Validation: Validate the obtained Kₓ against reaction-diffusion simulations or other experimental ground truths to ensure accuracy [19].

Computational Validation Workflow

The rise of AlphaFold2 (AF2) has dramatically expanded the structural coverage of the human transmembrane proteome. However, a predicted structure must be critically evaluated within the context of the membrane.

- Workflow Diagram:

- Membrane Embedding: Use specialized databases and tools like the TmAlphaFold database to position the predicted protein structure within the calculated plane of the lipid bilayer [20].

- Quality Filtering: The TmAlphaFold database applies a series of filters to detect common errors, such as the erroneous embedding of globular domains in the membrane or conflicts with independent topography predictions. Structures are assigned a quality level (Failed, Poor, Medium, Good, Excellent) based on the number of passed filters [20]. For example, 97% of structures in the "Excellent" category have a topography that matches the reference data [20].

- Topography Comparison: Compare the predicted transmembrane topology (number and position of transmembrane helices) against high-quality reference data from experimental structures or trusted topology prediction databases [20].

- Structural Analysis:

- Hydrophobic Matching: Analyze whether the length of the predicted transmembrane domains is compatible with the hydrophobic thickness of the presumed native membrane. A significant mismatch can indicate a stability issue or a need for structural refinement [15].

- Aromatic Residues: Verify the presence of aromatic residues (Tryptophan, Tyrosine) near the lipid-water interface, a hallmark of native membrane protein structures [12].

- pLDDT Confidence: Examine the per-residue confidence score (pLDDT). The distribution of these values in transmembrane regions shows that AF2 is typically more certain for higher-quality predictions [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents for Membrane Protein Structure Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Validation | Example Use-Case |

|---|---|---|

| Synthetic Lipids (e.g., DMPC, DLPC, DOPE) | Form defined model membranes (vesicles, planar bilayers) of specific thickness and charge to test hydrophobic matching and lipid requirements [15] [18]. | Determining the effect of bilayer thickness on ion channel function in CBBs [17]. |

| Cholesterol | Modulates bilayer fluidity, mechanical strength, and permeability. Essential for mimicking mammalian plasma membrane properties [14] [18]. | Incorporated into vesicles to study its effect on the binding affinity of a peripheral protein via FCS [19]. |

| Detergents | Solubilize membrane proteins for initial purification, but are replaced by lipids for functional studies. | Used in the initial reconstitution of proteins into liposomes for CBB experiments [17]. |

| Fluorophores (Photostable) | Label proteins or lipids for tracking and interaction studies using techniques like FCS and single-molecule imaging [19]. | Covalently attached to an antibody to quantify its membrane association constant via FCS [19]. |

| TmAlphaFold Database | Provides pre-embedded AF2 structures and a quality assessment from a "membrane point of view," flagging potentially erroneous models [20]. | First-pass evaluation of a newly predicted GPCR structure before committing to experimental studies. |

The lipid bilayer is an active participant in defining the native structure and function of membrane proteins. For researchers engaged in the validation of predicted structures, moving beyond in-silico metrics to functional assays within a bilayer context is paramount. The integrated application of computational tools like TmAlphaFold, biophysical techniques like FCS, and functional assays in systems like Contact Bubble Bilayers provides a robust, multi-faceted validation pipeline. By rigorously applying these protocols and leveraging the listed reagents, scientists can bridge the gap between static prediction and biological reality, significantly accelerating drug discovery and our understanding of membrane protein biology.

{ /article }

Validation in Practice: A Toolkit of Experimental and Computational Approaches

In the field of membrane protein structural biology, the emergence of sophisticated AI-based structure prediction tools has underscored the critical need for robust experimental validation. While predictive models can provide accurate folds for many proteins, they often fall short in capturing atomic-level details critical for understanding function, dynamic processes, and ligand interactions [21] [22]. Experimental techniques—X-ray crystallography, cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy—provide indispensable validation through distinct but complementary approaches. For membrane proteins, which represent challenging targets due to their complexity and dynamic nature within lipid bilayers, this multi-technique validation framework is particularly vital for confirming mechanistic hypotheses and guiding drug discovery [23] [24]. This article outlines detailed protocols and application notes for leveraging these three principal methods in validating predicted membrane protein structures.

Technique-Specific Application Notes

X-ray Crystallography

X-ray crystallography remains the dominant workhorse for determining high-resolution structures of biological macromolecules, accounting for approximately 66% of all protein structures deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) in 2023 [25]. The technique provides atomic-resolution information, typically at resolutions better than 3.0 Å, enabling researchers to visualize amino acid side chains, ligand binding modes, and detailed molecular interactions [26]. For membrane proteins, crystallography has been instrumental in elucidating mechanisms of transporters, channels, and receptors, though it presents specific challenges for these hydrophobic targets that require specialized approaches such as lipidic cubic phase (LCP) crystallization to maintain protein stability and function [23] [21].

The exceptional value of crystallography in validation lies in its ability to produce unambiguous electron density maps against which predicted atomic coordinates can be rigorously tested. This is particularly crucial for confirming the identity and binding pose of small molecule ligands in drug discovery applications [21]. Recent advancements have pushed the boundaries of the technique, with reports of atomic-resolution (1.09 Å) structures revealing double conformations, providing unprecedented detail for validating dynamic structural features [27].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Cryo-EM has undergone a revolutionary transformation, with its contribution to new PDB deposits surging from nearly negligible in the early 2000s to approximately 31.7% by 2023 [25]. This technique images protein specimens that have been flash-frozen in vitreous ice, preserving them in a near-native hydration state without the need for crystallization—a significant advantage for membrane proteins and large complexes that are difficult to crystallize [23]. Modern direct electron detectors and advanced image processing software now enable cryo-EM to achieve near-atomic resolution for many targets, with recent breakthroughs demonstrating its capability to resolve hydrogen atom positions and water networks, features previously accessible only through high-resolution crystallography [27].

For validation of membrane protein structures, cryo-EM is particularly valuable for studying large complexes in lipid environments and capturing multiple conformational states that may be averaged in crystal lattices. The ability to image proteins in nanodiscs or liposomes allows researchers to validate structural predictions under conditions that more closely mimic the native membrane environment [23] [24].

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

NMR spectroscopy, while contributing a smaller proportion (approximately 1.9% in 2023) to the total structures in the PDB, offers unique capabilities for validation that complement the other techniques [25]. Unlike the static snapshots provided by crystallography and cryo-EM, NMR captures proteins in solution and can probe structural dynamics, conformational heterogeneity, and functional processes in real time [22]. For membrane proteins, solution NMR is generally applicable to smaller targets or domains, while solid-state NMR can be used for proteins in lipid bilayers.

NMR produces spectral fingerprints of biomolecules at the atomic scale, providing information on structure, interactions, and motions occurring in solution [22]. This makes it exceptionally powerful for validating dynamic regions, disordered segments, and allosteric mechanisms that are often misrepresented in computational predictions. NMR can also directly monitor ligand binding and assess binding affinity and kinetics, offering a robust method for validating predicted protein-drug interactions [21] [22].

Comparative Analysis of Structural Techniques

Table 1: Key characteristics of the three major structural biology techniques

| Parameter | X-ray Crystallography | Cryo-EM | NMR Spectroscopy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Typical Resolution | Atomic (1-3 Å) | Near-atomic to atomic (1.5-4 Å) | Atomic (based on constraints) |

| Sample Requirements | High-quality crystals | Purified protein in solution | Isotopically labeled protein in solution |

| Sample State | Crystalline solid | Vitreous ice (near-native) | Solution or solid state |

| Throughput | High (once crystals obtained) | Medium to high | Low to medium |

| Information Type | Static snapshot | Multiple states possible | Dynamic in real time |

| Membrane Protein Challenges | Crystallization difficulty | Particle orientation, detergent optimization | Size limitation, signal overlap |

| Key Validation Strength | Ligand binding details | Native-like conformation validation | Dynamics and allostery |

Table 2: Recent advancements enhancing validation capabilities

| Technique | Recent Advancement | Validation Application |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | Serial Femtosecond Crystallography (SFX) | Visualizing radiation-sensitive centers and dynamic processes |

| Cryo-EM | Hydrogen atom resolution [27] | Validating protonation states and water networks |

| NMR | AI-assisted spectral analysis [22] | Enhanced interpretation of complex spectra for validation |

| All | MicroED for nanocrystals [23] | Structure determination from microcrystals |

Experimental Protocols for Membrane Protein Validation

X-ray Crystallography Workflow for Membrane Proteins

Protocol Title: X-ray Crystallography for Membrane Protein Structure Validation

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Detergents: n-Dodecyl-β-D-maltopyranoside (DDM), Lauryl Maltose Neopentyl Glycol (LMNG) - for protein solubilization and stabilization

- Lipidic Cubic Phase (LCP) Matrix: Monoolein - creates membrane-mimetic environment for crystallization

- Crystallization Screens: Commercially available sparse matrix screens (e.g., MemGold, MemSys) - identify initial crystallization conditions

- Cryoprotectants: Glycerol, ethylene glycol - protect crystals during flash-cooling

- Heavy Atom Compounds: Mercury, platinum, or selenium derivatives - for experimental phasing

Detailed Procedure:

Protein Expression and Purification:

- Express membrane protein using appropriate system (e.g., insect cell, mammalian)

- Solubilize in suitable detergent (e.g., DDM) maintaining protein stability and function [21]

- Purify to homogeneity using affinity, size exclusion, and ion exchange chromatography

Crystallization:

- Concentrate protein to 5-50 mg/mL depending on target [21]

- Set up initial crystallization trials using hanging drop or sitting drop vapor diffusion

- For challenging targets, employ LCP crystallization by mixing protein with monoolein matrix [23]

- Incubate at stable temperatures (4°C or 20°C) for days to weeks, monitoring crystal growth

- Optimize initial crystal hits by fine-tuning pH, precipitant concentration, additives

Data Collection:

Data Processing and Structure Determination:

- Process data: index, integrate, and scale diffraction images [28]

- Solve phase problem using molecular replacement (if homologous structure exists) or experimental phasing (SAD/MAD) [25]

- Build initial model into electron density map and iteratively refine

- Validate final model using geometric constraints and fit to electron density

Cryo-EM Workflow for Membrane Protein Validation

Protocol Title: Single-Particle Cryo-EM for Membrane Protein Structure Validation

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- EM Grids: UltrAuFoil, Quantifoil - graphene or gold supports with regular holes

- Detergents: Amphipols, nanodiscs - stabilize membrane proteins in solution

- Vitrification System: Thermo Fisher Vitrobot - automated plunge freezer for consistent ice thickness

- Negative Stains: Uranyl acetate, ammonium molybdate - for initial sample quality assessment

- Direct Electron Detectors: Falcon, K2, or K3 cameras - high-resolution data collection

Detailed Procedure:

Sample Preparation and Optimization:

Grid Preparation and Vitrification:

- Apply 3-4 μL of sample to freshly plasma-cleaned EM grid

- Blot with filter paper to create thin liquid film (optimize blot time and force)

- Plunge freeze into liquid ethane cooled by liquid nitrogen [29]

- Store grids under liquid nitrogen until data collection

Data Collection:

- Screen grids to identify areas with optimal ice thickness and particle distribution

- Collect dataset of thousands of movies at multiple exposures and defocus values

- Use beam-image shift or serial data collection for high-throughput acquisition

Data Processing and Reconstruction:

- Preprocess movies: motion correction, CTF estimation [30]

- Autopick particles followed by manual curation to remove false positives

- Perform 2D classification to select homogeneous particle subsets

- Generate initial model ab initio or using existing structure as reference

- Iteratively refine 3D reconstruction with imposed symmetry if applicable

- Sharpen map and build atomic model, refining against map

NMR Workflow for Membrane Protein Dynamics Validation

Protocol Title: NMR Spectroscopy for Membrane Protein Dynamics Validation

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Isotope-Enriched Media: 15N-ammonium chloride, 13C-glucose - for uniform isotopic labeling

- Deuterated Solvents: D2O, deuterated detergents - reduce background signals

- Membrane Mimetics: Bicelles, nanodiscs - maintain native-like lipid environment

- NMR Tubes: Shigemi tubes - minimize sample volume requirements

- Cryoprobes: High-sensitivity NMR probes with cooled electronics

Detailed Procedure:

Sample Preparation with Isotopic Labeling:

- Express protein in E. coli or other system using minimal media with 15N-ammonium chloride and/or 13C-glucose [21]

- For larger proteins, incorporate 2H labeling to reduce relaxation effects

- Solubilize membrane protein in appropriate detergent (e.g., DPC, SDS) or incorporate into bicelles/nanodiscs

- Concentrate to 200-500 μM in 250-500 μL volume [21]

Data Acquisition:

- Collect 2D 1H-15N HSQC spectrum as fingerprint of protein fold and stability

- Acquire triple-resonance experiments (HNCA, HNCOCA, CBCACONH) for backbone assignment

- Obtain 13C- and 15N-edited NOESY spectra for distance constraints

- Perform dynamics experiments (T1, T2, heteronuclear NOE) to probe molecular motions

Data Processing and Analysis:

- Process data with appropriate apodization functions and zero-filling

- Assign backbone and sidechain resonances using iterative approach

- Calculate structures using distance and dihedral constraints with simulated annealing

- Analyze dynamics from relaxation data and chemical exchange phenomena

Validation Against Predicted Structures:

- Compare experimental chemical shifts with those back-calculated from predicted structures

- Validate NOE distance constraints against predicted atomic distances

- Assess conformational heterogeneity and dynamics not captured in static models

Integrative Validation Strategy for Membrane Proteins

For comprehensive validation of predicted membrane protein structures, an integrative approach combining multiple techniques provides the most robust assessment. Crystallography offers high-resolution snapshots of specific states, cryo-EM captures structural heterogeneity in near-native conditions, and NMR probes dynamics and allostery in solution [22] [24]. Together, these techniques can validate different aspects of a predicted structure, from overall fold to specific atomic interactions.

Recent studies of membrane proteins highlight the power of this integrated approach. For example, research on the CLC-ec1 chloride/proton antiporter combined structural information with computational analyses of lipid dynamics to reveal how lipid composition influences dimerization through preferential solvation rather than specific binding sites [24]. Such insights would be impossible without complementary structural data from multiple techniques.

For drug discovery applications, crystallography provides detailed ligand binding information, cryo-EM reveals conformational changes induced by drug binding, and NMR can track binding kinetics and allosteric effects in real time [21] [22]. This multi-technique validation framework ensures that predicted membrane protein structures used for drug design accurately represent biological reality, ultimately increasing the success rate of structure-based drug discovery programs.

The accurate prediction of membrane protein structures represents a significant challenge in structural biology, with profound implications for basic research and drug development. The advent of deep learning-based structure prediction tools like AlphaFold2 (AF2) has revolutionized the field by providing accurate three-dimensional models of proteins from their amino acid sequences [31]. However, these predictions require rigorous validation, especially for membrane proteins whose functions are intimately tied to their lipid environments. Computational cross-checking through molecular dynamics (MD) simulations and AF2's intrinsic quality metrics—the predicted local distance difference test (pLDDT) and predicted aligned error (PAE)—provides a powerful framework for assessing model reliability before investing in costly experimental validations.

This application note details protocols for integrating these computational approaches to validate predicted membrane protein structures within the broader context of thesis research on membrane protein structural validation. We provide detailed methodologies, quantitative correlation data, and practical workflows to help researchers assess the quality and biological plausibility of their predicted models.

Understanding AlphaFold2 Confidence Metrics: pLDDT and PAE

AlphaFold2 generates two primary confidence metrics that are essential for evaluating prediction quality: pLDDT and PAE. The pLDDT score ranges from 0 to 100 and provides a per-residue estimate of local model confidence, with higher values indicating higher reliability [31]. The PAE matrix estimates the positional error between residue pairs after optimal alignment, with higher values indicating lower confidence in the relative positioning of structural elements [31] [32].

Interpretation Guidelines for Confidence Metrics

pLDDT Scores:

PAE Matrix:

- <5 Å: High confidence in relative domain positioning

- >10 Å: Low confidence in relative orientation [31]

For membrane proteins, specific challenges arise. AF2 may struggle with regions that interact with lipids, cofactors, or other membrane-embedded elements [31]. Additionally, the algorithm's training on structures from the Protein Data Bank, which may underrepresent certain membrane protein classes, can limit accuracy for some targets.

Molecular Dynamics Simulations as a Validation Tool

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a physics-based method to assess the stability and conformational dynamics of predicted structures. By simulating the movement of atoms over time, MD can identify unstable regions, unrealistic conformations, or misfolded structures that may not be apparent from static models [33] [34].

Key Analysis Metrics from MD Simulations

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) | Measures structural deviation from starting coordinates | Values >2-3Å may indicate instability or unfolding |

| RMSF (Root Mean Square Fluctuation) | Quantifies per-residue flexibility | Correlates with pLDDT; peaks indicate flexible regions |

| Distance Variation (σd) | Measures variation in distance between residue pairs | Correlated with PAE scores; identifies flexible domain linkages |

| Interaction Analysis | Examines protein-lipid and protein-cofactor contacts | Validates biological plausibility of membrane embedding |

Studies have demonstrated strong correlations between AF2 confidence metrics and dynamics observed in MD simulations. Research across 28 different proteins revealed that a 1 Å increase in distance variation (σd,20) corresponds to a 9-unit decrease in pLDDT score, with an overall correlation coefficient of R=0.65 [35]. Similarly, PAE scores show correlation with distance variation matrices from MD (R=0.53), where a 1 Å increase in σd corresponds to a 0.7 Å increase in PAE [35].

Integrated Workflow for Cross-Validation

The following workflow provides a systematic approach for cross-validating predicted membrane protein structures:

Protocol 1: Initial AF2 Model Assessment

Purpose: To identify potential problematic regions in AF2 models prior to MD simulations.

- Generate AF2 models using ColabFold [31] or local installation with membrane-appropriate settings

- Extract confidence metrics:

- Parse pLDDT scores from B-factor column of PDB files

- Generate PAE matrix using AF2 output utilities

- Identify low-confidence regions:

- Residues with pLDDT < 70 warrant special attention

- Domain interfaces with PAE > 5 Å indicate uncertain relative positioning

- Document regions of concern for focused analysis during MD validation

Protocol 2: MD Simulation Setup for Membrane Proteins

Purpose: To establish biologically realistic MD systems for validating predicted membrane protein structures.

System Preparation:

Simulation Parameters (all-atom):

- Force Field: CHARMM36m [32] [35] or a99SB-disp [35]

- Water Model: TIP3P [32] or modified TIP3P [32]

- Neutralization: Add 0.15 M NaCl [32]

- Minimization: 50,000 steps [32]

- Equilibration: Gradual heating to 300K, followed by NPT equilibration (1 atm, 300K) [32]

- Production: ≥100 ns (longer for large-scale conformational changes) [32]

Enhanced Sampling (optional):

- For complex conformational transitions, consider replica-exchange MD or metadynamics

- Implement bias-exchange methods for peripheral membrane protein binding [34]

Protocol 3: Correlation Analysis Between AF2 Metrics and MD Data

Purpose: To quantitatively compare AF2 confidence metrics with dynamics observed in MD simulations.

Extract flexibility metrics from MD:

- Calculate RMSF for each residue after alignment to initial structure

- Compute distance variation matrix (σd):

- For each residue pair (i,j), calculate standard deviation of Cα-Cα distance across trajectory [35]

- Calculate localized distance variation (σd,20): average standard deviation of distances to 20 nearest residues [35]

Perform correlation analysis:

- Correlate pLDDT with σd,20 using linear regression

- Compare PAE matrix with σd matrix using 2D correlation

- Use statistical measures: Pearson correlation (R), Spearman's rank correlation (ρ) [35]

Interpret correlation results:

Quantitative Correlation Data

The table below summarizes typical correlation values between AF2 metrics and MD-derived dynamics observed across multiple protein systems:

Table 1: Correlation Between AF2 Metrics and MD Dynamics

| Correlation Pair | Overall Correlation (R) | Range Across Proteins | Regression Equation | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| pLDDT vs σd,20 | -0.65 | 0.24 to 0.99 [35] | pLDDT = -9 × σd,20 + 101 [35] | High pLDDT correlates with low flexibility |

| PAE vs σd | 0.53 | 0.25 to 0.92 [35] | PAE = 0.7 × σd + 2.4 [35] | High PAE correlates with high distance variation |

| pLDDT vs RMSF | ~ -0.65* | Variable by system [32] | System-dependent | Similar to σd,20 correlation |

*Note: Correlation between pLDDT and RMSF is similar to pLDDT vs σd,20 based on reported data [32] [35].

Case Study: Validation of a Peripheral Membrane Protein C2 Domain

To illustrate the application of these protocols, we present a case study on validating a predicted C2 domain structure, a common membrane-binding module in signaling proteins.

Experimental Protocol

System: C2 domain of cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2-C2) [36]

AF2 Prediction:

- Generated AF2 models using ColabFold

- Observed high pLDDT (>85) for β-strand core, moderate scores (60-75) for calcium-binding loops

MD Simulation Setup:

Validation Analysis:

- Monitored maintenance of calcium-binding loops during simulation

- Analyzed lipid rearrangement around protein surface

- Verified membrane docking site formation with hydrophobic bottom and hydrophilic rim [36]

Key Findings:

- The C2 domain assembled and optimized its own lipid docking site through local lipid remodeling [36]

- Lipid phosphate groups provided outer-sphere calcium coordination through intervening water molecules [36]

- Simulation confirmed biological plausibility of AF2-predicted structure in membrane environment

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Membrane Protein Validation

| Category | Specific Tool/Resource | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Structure Prediction | AlphaFold2/ColabFold [31] | Protein structure prediction from sequence | Use AlphaFold-Multimer for complexes [31] |

| MD Force Fields | CHARMM36m [32] [35] | All-atom protein force field | Improved for folded and disordered proteins [32] |

| MD Force Fields | a99SB-disp [35] | All-atom protein force field | Accurate for folded and disordered states [35] |

| Membrane Builders | CHARMM-GUI [34] | Membrane system preparation | Supports various lipid types and compositions |

| Analysis Tools | Bio3D [32] | MD trajectory analysis | Calculates RMSD, RMSF, PCA |

| Specialized MD | MARTINI3 [35] | Coarse-grained force field | Enables longer timescales; use with AF-ENM [35] |

| Quality Metrics | pLDDT/PAE [31] | Model confidence scores | Integrated in AF2 output |

The integration of AlphaFold2 confidence metrics with molecular dynamics simulations provides a powerful framework for validating predicted membrane protein structures. The protocols outlined in this application note enable researchers to identify potential problematic regions in AF2 models, assess their stability in biologically relevant environments, and make informed decisions about which predictions to prioritize for experimental characterization. As these computational methods continue to advance, they will play an increasingly important role in accelerating membrane protein research and drug discovery, particularly for targets that resist conventional structural determination methods.

For thesis research focused on validating predicted membrane protein structures, this cross-validation approach provides a rigorous computational methodology that complements and guides experimental efforts, ultimately enhancing the reliability of structural models used to understand membrane protein function and facilitate drug development.

The biological membrane is a complex and dynamic environment, and understanding how lipids influence membrane protein structure and function is a critical challenge in structural biology. For research focused on validating predicted membrane protein structures, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provide an indispensable tool for probing the molecular-scale interactions between proteins and their lipid environment. A key concept emerging from recent studies is preferential solvation, a thermodynamic phenomenon where certain lipid species become locally enriched around a protein not through specific, long-lived binding, but due to their ability to better solvate the protein's surface in different conformational states [24]. This dynamic process allows the lipid membrane composition to actively modulate protein conformational equilibria and oligomerization.

This protocol details the application of MD simulations to investigate preferential lipid solvation, providing a framework for validating and refining computational models of membrane proteins. By quantifying how different lipid species distribute themselves around a protein, researchers can gain critical insights into the driving forces behind membrane-mediated protein behavior, thereby strengthening the validation of predicted structures within a biologically realistic context.

Theoretical Framework: Preferential Solvation in Membranes

Preferential solvation describes a scenario where the local lipid composition at the protein-lipid interface differs from the composition of the bulk membrane. This occurs because the protein's surface, with its unique chemical and topological features, presents a solvation environment that may be more favorably accommodated by certain lipid types [24]. For instance, a region of hydrophobic mismatch—where the protein's hydrophobic thickness does not match that of the bilayer—might be better solvated by lipids with shorter or more flexible acyl chains.

It is crucial to distinguish this mechanism from specific lipid binding. Specific binding involves high-affinity, long-lived interactions, often with a saturable binding curve. In contrast, preferential solvation is a weak, non-saturating linkage effect where the enrichment of a lipid species scales with its concentration in the bulk membrane and does not involve prolonged immobilization [24]. This distinction has profound implications: preferential solvation enables the membrane to act as a tunable solvent that can broadly regulate protein conformation and assembly in response to changes in lipid composition, rather than acting through a few discrete, ligand-like interactions.

Computational Protocols

This section provides a detailed, step-by-step methodology for setting up, running, and analyzing MD simulations to study preferential solvation of membrane proteins.

System Setup and Equilibration

Objective: To construct a simulateable model of a membrane protein embedded in a complex lipid bilayer.

Protocol Steps:

Initial Protein Placement:

- Obtain the protein structure from a prediction server, experimental data (e.g., PDB), or a homology model.

- Orient the protein within the membrane using tools like PPM (Positioning of Proteins in Membranes) server or the implicit membrane model in CHARMM-GUI to ensure the transmembrane domains align correctly with the anticipated bilayer region [12].

Membrane and Solvent Building:

- Use CHARMM-GUI (http://www.charmm-gui.org) to build the lipid bilayer around the protein [37]. This platform simplifies the process of creating complex, asymmetric membranes.

- Select lipid compositions that reflect the biological system of interest or are designed to test specific hypotheses (e.g., mixtures of long-chain (e.g., POPC) and short-chain (e.g., DLPC) lipids) [24].

- Solvate the system with water (e.g., TIP3P model) and add ions (e.g., 0.15 M NaCl) to neutralize the system and achieve physiological ionic strength.

Force Field Selection and Parameterization:

- Use a modern, well-validated force field. For all-atom (AA) simulations, CHARMM36 is highly recommended for lipids and proteins [37]. For coarse-grained (CG) simulations, the MARTINI force field is a standard choice, offering increased sampling efficiency [24] [37].

- Parameterizing Non-Standard Residues: For lipidated proteins (e.g., prenylated or palmitoylated), obtain parameters from the CHARMM36 force field if available. If not, use the CGenFF (CHARMM General Force Field) toolkit or the ffTK (force field ToolKit) plugin in VMD to generate parameters for the lipid-modified amino acids [37].

System Equilibration:

- Perform a multi-stage equilibration with gradually releasing positional restraints, first on the lipid tails, then on the protein backbone and side chains.

- Typical equilibration lasts for >100 ns in AA and >1 µs in CG, monitoring system properties (e.g., area per lipid, membrane thickness, protein RMSD) for stability before starting production runs.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for MD Simulations of Membrane Proteins

| Item | Function/Description | Example Sources/Tools |

|---|---|---|

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-based platform for building complex simulation systems, including membranes with diverse lipid compositions. | [12] [37] |

| CHARMM36 Force Field | All-atom force field providing parameters for proteins, lipids, and carbohydrates; optimized for biomolecular simulations. | [12] [37] |

| MARTINI Force Field | Coarse-grained force field that groups atoms into beads, enabling longer timescale simulations of large systems. | [24] [37] |

| CGenFF/ffTK | Tools for generating force field parameters for non-standard molecules, such as post-translationally lipidated amino acids. | [37] |

| GROMACS/NAMD | High-performance molecular dynamics simulation software packages for running AA and CG simulations. | [12] [37] |

Production Simulations and Analysis

Objective: To simulate the system and quantify lipid distributions and dynamics to identify preferential solvation.

Protocol Steps:

Running Production Simulations:

- Run multiple independent replicas (at least 3) to ensure statistical robustness.

- Simulation length must be sufficient to observe multiple lipid exchange events at the protein-solvation shell. For AA, this typically requires >1 µs. For CG, tens to hundreds of microseconds may be needed [24] [38].

- Maintain constant temperature and pressure (e.g., NPT ensemble) using standard thermostats (e.g., Nosé-Hoover) and barostats (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

Analysis of Preferential Solvation:

- Radial Distribution Function (RDF): Calculate the RDF (g(r)) of specific lipid atoms (e.g., phosphorus) around the protein. A peak indicates spatial correlation and potential enrichment [39].

- Lipid Density Maps: Create 2D density maps of different lipid species in the plane of the membrane around the protein to visualize areas of enrichment (hot spots) and depletion.

- Coordination Number Analysis: Determine the average number of a specific lipid type within a defined cutoff distance (e.g., the first solvation shell) from the protein surface [39].

- Quantifying Enrichment: Calculate a preferential solvation parameter. This can be defined as the local mole fraction of a lipid near the protein divided by its bulk mole fraction. A value >1 indicates enrichment; <1 indicates depletion [24].

- Residence Times: Calculate the mean residence time (MRT) of lipids in the first solvation shell. Preferential solvation is characterized by short residence times, confirming a dynamic process rather than stable binding [24] [39].

The following workflow diagram outlines the key stages of this protocol, from system setup to analysis.

Application Notes: Integrating MD into a Validation Pipeline

Preferential solvation analysis provides a powerful link between computational models and experimental observables, which is central to a robust validation pipeline.

- Linking to Experimental Data: Use MD simulations to compute theoretical observables that can be directly compared with experiment. For instance, calculate scattering form factors from simulation trajectories for comparison with X-ray or neutron scattering data. Alternatively, use the lipid enrichment profiles to rationalize results from mass spectrometry-based lipidomics studies [24] [40].

- Case Study: CLC-ec1 Dimerization: A prime example involves the CLC-ec1 chloride/proton antiporter. MD simulations revealed that short-chain DL lipids preferentially solvate the exposed dimerization interface of the monomer. This enrichment, driven by the need to solvate a membrane defect, creates a thermodynamic bias against dimerization. The simulations showed no long-lived lipid binding, confirming a preferential solvation mechanism, and the computed changes in dimerization free energy matched experimental measurements [24].

- Implications for Drug Discovery: Many drug targets, such as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) and the oncoprotein KRAS, are membrane proteins whose activity is modulated by lipids. MD simulations can map "hot spots" on the protein surface where specific lipids preferentially accumulate. This information can reveal allosteric regulatory sites and inform the design of small molecules that disrupt pathogenic protein-lipid interactions [37] [41].

Data Interpretation and Presentation

Effective quantification and presentation of data are essential for communicating findings on preferential solvation.

Table 2: Key Metrics for Analyzing Preferential Solvation from MD Trajectories

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Radial Distribution Function (RDF) Peak | Measures the probability of finding a lipid at distance (r) from the protein relative to a random distribution. | A distinct peak in the first 5-10 Å indicates spatial correlation and potential enrichment of that lipid species. |

| Local vs. Bulk Lipid Ratio | The ratio of a lipid's mole fraction in the first solvation shell to its mole fraction in the bulk membrane. | A ratio > 1 indicates preferential accumulation; < 1 indicates depletion. The magnitude quantifies the strength of the effect. |

| Mean Residence Time (MRT) | The average time a lipid remains within the first solvation shell before exchanging with the bulk. | Short MRTs (ns-µs, depending on resolution) are characteristic of dynamic preferential solvation, not static binding. |

| Solvation Free Energy (ΔG) | The change in free energy associated with transferring the protein from one lipid environment to another. | A negative ΔG indicates more favorable solvation in the target environment. This can be calculated for different protein states (e.g., monomer vs. dimer) [24]. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship between simulation outputs and the final mechanistic conclusion, highlighting the key analyses involved.

Molecular dynamics simulations provide a unique atomic-resolution lens through which to view the dynamic and regulatory lipid environment of membrane proteins. The framework of preferential solvation offers a powerful thermodynamic explanation for how lipid composition can tune protein function without the need for specific binding. By integrating the protocols outlined here—from careful system setup to quantitative analysis of lipid dynamics—researchers can critically assess and validate predicted membrane protein structures, moving beyond static snapshots to a dynamic understanding of protein behavior in a biologically realistic membrane milieu. This approach is fundamental for advancing both basic science and the development of therapeutics targeting membrane proteins.

Validating predicted membrane protein structures requires moving beyond static snapshots to understand their dynamic biological activity. Membrane proteins, which constitute 30% of the human genome, perform crucial physiological functions including ion transport, signal transduction, and substrate translocation [42]. Their malfunction is implicated in numerous diseases, making them prime therapeutic targets [42]. However, correlating atomic-level structures with functional states remains challenging due to the dynamic nature of proteins and the complexity of their membrane environment [43] [44]. This Application Note provides integrated protocols to experimentally link validated membrane protein structures to biological function through biophysical, computational, and single-molecule approaches.

Integrated Methodological Framework

Core Experimental Strategy

A robust workflow for correlating structure with function combines bioinformatics, molecular simulations, and experimental validation in near-native membrane environments. The integrated approach outlined below enables researchers to observe ligand-dependent conformational dynamics of integral membrane proteins in situ [43].

Table 1: Core Techniques for Structure-Function Correlation

| Technique | Key Applications | Temporal Resolution | Spatial Resolution | Sample Requirements |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single-molecule FRET (smFRET) | Monitoring intra-protein conformational changes [43] | Milliseconds to seconds [44] | 1-10 nm distance range [43] | Dual-labeled protein in nanodiscs or liponanoparticles |

| High-Speed Atomic Force Microscopy Height Spectroscopy (HS-AFM-HS) | Monitoring sub-millisecond conformational dynamics [44] | 10 μs (HS mode) [44] | ~1 nm lateral, ~0.1 nm vertical [44] | Membrane-reconstituted proteins in lipid bilayers |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations | Atomistic details of conformational dynamics and energy landscapes [44] | Nanoseconds to milliseconds | Atomic level | Atomic coordinates from crystal structures or predictions |

| Single-channel Electysiology | Monitoring functional ion channel gating dynamics [44] | Microsecond resolution | Current fluctuations in picoampere range | Membrane-reconstituted proteins in planar bilayers or patches |

Quantitative Structural Metrics for ABC Transporters

For ABC membrane protein structures, standardized quantitative metrics enable meaningful comparison between conformations and facilitate correlation with functional states. The following vectors and calculations provide objective characterization of structural features [45].

Table 2: Conformational Vectors (Conftors) for ABC Type I Exporter Analysis

| Vector Name | Structural Elements Connected | Measurement Type | Functional Correlation |

|---|---|---|---|

| TH4–5 and TH10–11 Conftors | Transmembrane helices 4-5 and 10-11 [45] | Relative orientation and distance | Inward-facing vs. outward-facing conformational states |

| NBD-NBD Distance | Nucleotide binding domains [45] | Center-of-geometry separation | ATP-binding driven dimerization status |

| TMD Tilting Angle | Transmembrane domain relative to membrane normal [45] | Angle between principal axis and membrane normal | Membrane insertion energetics and stability |