Validating Protein Structure Prediction for Snake Venom Toxins: From Computational Models to Therapeutic Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the validation of protein structure prediction tools for snake venom toxins, a diverse and challenging class of proteins.

Validating Protein Structure Prediction for Snake Venom Toxins: From Computational Models to Therapeutic Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the validation of protein structure prediction tools for snake venom toxins, a diverse and challenging class of proteins. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles of venom complexity, details the application of cutting-edge tools like AlphaFold2, ColabFold, and RFdiffusion, and addresses key troubleshooting and optimization strategies for low-abundance and difficult targets. Furthermore, it critically examines validation frameworks that integrate computational predictions with experimental data, such as epitope mapping and neutralization assays. By synthesizing recent advances, this review outlines a path for leveraging computational structural biology to accelerate the development of next-generation antivenoms and toxin-derived therapeutics.

The Complex Landscape of Snake Venom Toxins and Prediction Challenges

Understanding Snake Venom Proteome Diversity and Its Biomedical Significance

Snake venoms represent sophisticated biochemical arsenals comprising complex mixtures of proteins and peptides that have evolved to facilitate prey subjugation and digestion [1]. The profound diversity of these venoms, driven by factors such as evolutionary lineage, geographical distribution, and ecological pressures, presents significant challenges for comprehensive characterization while simultaneously offering immense potential for biomedical discovery [1]. Understanding this diversity at structural and functional levels is critical for developing effective antivenoms and harnessing venom components for therapeutic applications, particularly in an era of rising antibiotic resistance [1] [2].

The global health burden of snakebite envenomation is substantial, with the World Health Organization estimating 5.4 million bites annually resulting in 81,000 to 138,000 deaths worldwide [3]. Traditional antivenoms, derived from animal immunization with crude venoms, often suffer from limited specificity, batch-to-batch variability, and inadequate neutralization of key toxins [3] [4]. These limitations underscore the urgent need for rationally designed therapeutics based on detailed understanding of venom composition and structure-function relationships [5].

This review examines contemporary approaches for characterizing snake venom proteomes, with particular emphasis on methodological advances in proteomics, structural prediction tools, and computational biology that are transforming venom research. By comparing the capabilities and limitations of these technologies, we provide researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate strategies based on their specific investigative goals.

Compositional Diversity of Snake Venoms: Major Toxin Families

Snake venoms contain numerous protein families that contribute to their pathological effects. The relative abundance of these families varies considerably across species, influencing venom toxicity and medical implications.

Table 1: Major Toxin Families in Snake Venoms and Their Characteristics

| Toxin Family | Key Enzymatic Activities | Primary Pathological Effects | Relative Abundance in Venoms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Metalloproteinases (SVMPs) | Proteolysis of extracellular matrix proteins | Hemorrhage, tissue damage, coagulopathy | 20-60% in viperid venoms [1] |

| Phospholipases A₂ (PLA₂s) | Hydrolysis of phospholipids | Neurotoxicity, myotoxicity, hemolysis, antimicrobial activity | 5-47% depending on species [3] [6] |

| Three-Finger Toxins (3FTxs) | Receptor antagonism (e.g., nAChRs) | Neurotoxicity, cytolysis, anticoagulation | Up to 54-81% in elapid venoms [6] |

| Serine Proteases | Fibrinogenolysis, factor activation | Coagulopathy, hypotension | ~11-17% in some viperid venoms [3] |

| C-type Lectins | Platelet receptor binding | Platelet aggregation/inhibition | Variable (e.g., 17% in E. ocellatus) [3] |

Comparative proteomic studies reveal striking interspecies variations in venom composition. For instance, iTRAQ-based proteomic analysis of Nigerian snake venoms demonstrated that while Echis ocellatus and Bitis arietans venoms are dominated by metalloproteinases (53% and 47%, respectively) and share similar profiles of C-type lectins and serine proteases, Naja nigricollis venom contains three-finger toxins as its most abundant component (9%) with substantially lower metalloproteinase content (3%) [3]. Similarly, analysis of Micrurus ephippifer venom revealed a predominance of 3FTxs (54%) and PLA₂s (29%), characteristic of elapid venoms [6].

Beyond these quantitative differences, venom complexity is amplified by the presence of multiple proteoforms - structural variants of proteins generated through post-translational modifications, alternative splicing, and genetic polymorphisms [5]. These proteoforms exhibit functional variations that are not captured by conventional bottom-up proteomics approaches, necessitating advanced analytical techniques for comprehensive characterization.

Methodological Approaches in Venom Proteomics

Mass Spectrometry-Based Proteomics

Mass spectrometry has become the cornerstone of modern venom proteomics, enabling high-resolution characterization of venom compositions. Two primary workflows dominate the field:

Bottom-up proteomics involves digesting venom proteins with trypsin followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) analysis of the resulting peptides. This approach, exemplified in the characterization of Micrurus ephippifer venom where tryptic peptide sequences matched 46 proteins in the SwissProt/UniProt database, provides extensive coverage of venom components but often fails to distinguish between protein isoforms and proteoforms [6].

Top-down proteomics analyzes intact proteins without enzymatic digestion, preserving information about post-translational modifications and proteoforms. While this method offers more comprehensive characterization of venom heterogeneity, it faces challenges in detecting low-abundance proteins and requires specialized instrumentation [5].

Table 2: Comparison of Venom Proteomics Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Advantages | Limitations | Representative Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| iTRAQ Proteomics | Multiplexing capability (4-8 samples), relative quantification, high reproducibility | Requires extensive sample preparation, limited dynamic range | Quantification of toxin abundance across species [3] |

| Bottom-up Proteomics | High sensitivity, comprehensive protein identification, well-established workflows | Loss of proteoform and structural information, incomplete sequence coverage | Cataloging venom compositions at toxin family level [6] [5] |

| Top-down Proteomics | Preservation of proteoform information, identification of PTMs | Technical complexity, limited throughput, detection challenges for large proteins | Characterization of protein isoforms and modified variants [5] |

| Transcriptomics | Identification of low-abundance toxins, complete sequence information | May not reflect secreted venom composition, tissue availability limitations | Venom gland analysis of M. ephippifer (2,885 transcripts assembled) [6] |

iTRAQ (Isobaric Tags for Relative and Absolute Quantitation) technology has emerged as a powerful tool for comparative venom proteomics, enabling simultaneous quantification of protein abundance across multiple samples [3]. The iTRAQ workflow involves several critical steps: (1) protein extraction and reduction/alkylation of disulfide bonds; (2) tryptic digestion of proteins into peptides; (3) labeling of peptides with isobaric tags; (4) LC-MS/MS analysis; and (5) database searching and quantitative analysis [3]. This approach has been successfully applied to identify fine-scale differences in toxin families across species and geographical populations, providing insights crucial for targeted antivenom development.

Structural Characterization Techniques

Understanding venom protein function requires detailed structural information that goes beyond primary sequences. Several biophysical techniques are employed for this purpose:

X-ray crystallography provides atomic-resolution structures but requires high-quality crystals that can be challenging to obtain for flexible venom proteins [5]. Cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM) enables structure determination of large complexes without crystallization, making it suitable for studying venom protein interactions [5]. Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy offers solution-state structural information and insights into dynamics but is limited by protein size [5].

The integration of these high-resolution structural techniques with functional assays has proven particularly valuable for understanding mechanisms of toxin action. For example, structural studies of three-finger toxins have revealed how conserved structural folds can produce diverse pharmacological effects through variations in loop sequences and molecular surfaces [4].

Computational and Bioinformatics Approaches

Protein Structure Prediction Tools

The application of machine learning-based structure prediction tools has transformed venom toxin characterization, particularly for proteins lacking experimental structures. A comprehensive evaluation of three modeling tools on over 1,000 snake venom toxin structures revealed that AlphaFold2 (AF2) performed best across all assessed parameters, with ColabFold (CF) scoring slightly worse while being computationally less intensive [7].

These tools exhibit varying performance depending on toxin characteristics. For small toxins like 3FTxs, predictions are highly accurate, while larger toxins with flexible regions (e.g., snake venom metalloproteinases) present greater challenges [7]. All tools struggled with regions of intrinsic disorder, particularly flexible loops and propeptide regions, though they performed well in predicting functional domains [7]. This underscores the importance of exercising caution when working with computational models, especially for large toxins containing flexible regions.

Deep Learning and De Novo Design

Recent advances in deep learning have enabled not only structure prediction but also the de novo design of proteins that interact with venom toxins. Researchers have used RFdiffusion to design proteins targeting three-finger toxins (3FTxs), achieving remarkable results [4]. Through limited experimental screening, they obtained designs with high thermal stability (Tm > 78°C for short-chain neurotoxin binder SHRT, Tm > 95°C for long-chain neurotoxin binder LNG), high binding affinity (Kd values in the nanomolar range), and near-atomic-level agreement with computational models [4].

These designed proteins effectively neutralized α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins in vitro and protected mice from lethal neurotoxin challenges, demonstrating the potential of computational approaches to generate novel therapeutics against venom toxins [4]. Similarly, the Venomics AI platform has been used to mine global venomics datasets, identifying 386 venom-encrypted peptides (VEPs) with potent antimicrobial activity against drug-resistant pathogens [2]. From 58 peptides selected for experimental validation, 53 (91.4%) exhibited activity against at least one pathogenic strain, with Arachnoserver-derived peptides showing particularly strong antimicrobial potential [2].

Epitope Prediction and Immunoinformatics

Computational immunology offers promising approaches for improving antivenom development through epitope prediction. Systematic reviews have identified that multitool prediction strategies consistently outperform single-tool approaches, particularly when structural and sequence-based models are combined [8]. However, reporting inconsistencies, limited negative data, and variable study designs impair direct comparison across studies [8].

The availability of structural data and toxin family characteristics emerged as key factors influencing prediction success [8]. Standardized frameworks for dataset selection, algorithm parameters, and validation rigor are critically needed to advance computational epitope discovery in venom research [8].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

iTRAQ-Based Quantitative Proteomics Protocol

Sample Preparation:

- Extract venom proteins using EDTA-containing buffer without SDS

- Reduce disulfide bonds with 10 mM DTT at 56°C for 1 hour

- Alkylate with 55 mM iodoacetamide in the dark for 45 minutes

- Quantity protein concentration using Bradford assay with BSA standards

Protein Digestion and Labeling:

- Digest 100 μg of protein with trypsin (enzyme-to-protein ratio 1:20) at 37°C for 4 hours

- Desalt resulting peptides using C18 spin columns

- Label peptides with iTRAQ 4plex reagent kit according to manufacturer's instructions

Mass Spectrometry Analysis:

- Analyze labeled peptides via LC-MS/MS using high-resolution mass spectrometer

- Perform data-dependent acquisition with dynamic exclusion

- Process data using Mascot and IQuant for protein identification and quantification

Validation:

- Perform one-dimensional SDS-PAGE for quality control

- Use biological and technical replicates to ensure reproducibility

- Confirm key findings with orthogonal methods when possible

Venom Toxin Neutralization Assay Protocol

Toxin Preparation:

- Isolate target toxins via size exclusion chromatography and RP-HPLC

- Characterize purity by SDS-PAGE and mass spectrometry

- Determine toxin activity using specific functional assays

In Vitro Neutralization:

- Pre-incubate toxins with neutralizing agents (designed proteins or antivenom) for 30 minutes at 37°C

- Assess receptor binding inhibition via ELISA or surface plasmon resonance

- Evaluate cellular effects using cell-based assays (e.g., neurite outgrowth for neurotoxins)

In Vivo Validation:

- Use murine models of envenomation with IACUC approval

- Administer toxin-neutralizing agent complexes via appropriate routes

- Monitor survival, clinical signs, and physiological parameters

- Perform histopathological examination of affected tissues

Research Reagent Solutions for Venom Proteomics

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Venom Proteomics

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteomic Reagents | iTRAQ/TMT labeling kits, trypsin, C18 columns, LC-MS grade solvents | Protein identification and quantification | Multiplexing capacity, labeling efficiency, compatibility with MS instrumentation |

| Bioinformatics Tools | AlphaFold2, ColabFold, HADDOCK, EVcouplings, APEX | Structure prediction, molecular docking, epitope mapping | Computational resources, accuracy for specific toxin families, validation requirements |

| Structural Biology | Crystallization kits, cryo-EM grids, NMR isotopes | High-resolution structure determination | Sample requirements, technical expertise, access to specialized facilities |

| Antivenom Development | Coralmyn antivenom, various polyvalent antivenoms | Neutralization studies, efficacy assessment | Species specificity, batch-to-batch variability, regulatory considerations |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | PC12 cells (neurite outgrowth), SH-SY5Y cells, primary neurons | Functional characterization of neurotoxins | Cell line authentication, relevance to human physiology, standardization of protocols |

The field of snake venom proteomics has evolved from simple cataloging of venom components to sophisticated integrative approaches that combine multiple omics technologies, structural biology, and computational predictions. This multidimensional characterization is essential for understanding venom complexity and harnessing its components for biomedical applications.

Future advancements will likely focus on several key areas: (1) improved computational methods that better handle flexible regions and rare proteoforms; (2) standardized frameworks for validating predicted epitopes and structures; (3) high-throughput screening platforms for functional characterization; and (4) integrative databases that combine structural, functional, and immunological data.

The convergence of these technologies promises to accelerate the development of next-generation antivenoms with improved efficacy and specificity while simultaneously unlocking the therapeutic potential of venom components for treating conditions ranging from antibiotic-resistant infections to neurodegenerative diseases. As these tools become more accessible and standardized, they will help democratize venom research, particularly in resource-limited settings where the burden of snakebite envenomation is highest.

Snake venoms represent a complex library of biologically active proteins and polypeptides, with key toxin families including Three-Finger Toxins (3FTx), Snake Venom Metalloproteinases (SVMPs), Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s), and Cysteine-Rich Secretory Proteins (CRISPs). These families provide an exceptional testing ground for validating computational protein structure prediction methods due to their diverse structural architectures, varied biological activities, and medical importance in snakebite envenoming—a neglected tropical disease claiming over 100,000 lives annually [9] [10] [4]. The accurate prediction of these toxin structures is a critical step toward developing novel therapeutics, including next-generation antivenoms, and offers insights into structure-function relationships that govern their pathological mechanisms.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Snake Venom Toxin Families

| Toxin Family | Typical Molecular Weight | Key Structural Features | Primary Biological Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Finger Toxins (3FTx) | 6-9 kDa [10] | Three β-stranded loops extending from a central core stabilized by 4-5 conserved disulfide bonds [9] | Neurotoxicity, cytotoxicity, cardiotoxicity [9] [10] |

| Snake Venom Metalloproteinases (SVMPs) | 20-100 kDa [11] [10] | Zinc-dependent enzymes with HEXXHXXGXXHD consensus sequence and Met-turn [12] | Hemorrhage, fibrin(ogen)olysis, apoptosis, platelet aggregation inhibition [11] [12] |

| Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) | 13-15 kDa [10] | Compact, multi-stranded β-sheet structure with α-helices [13] | Neurotoxicity, myotoxicity, membrane disruption [10] |

| Cysteine-Rich Secretory Proteins (CRISPs) | Information missing | Information missing | Information missing |

Structural Characteristics and Comparative Analysis

Three-Finger Toxins (3FTx)

3FTxs exhibit a characteristic three-finger fold maintained by four conserved disulfide bonds in the core, creating three β-stranded loops resembling three fingers of a hand [9]. These toxins typically contain 60-74 amino acid residues with 4-5 disulfide bridges, and while all share a similar fold, they recognize a broad range of molecular targets resulting in diverse biological activities [9]. Some 3FTxs feature an additional fifth disulfide bridge in loop I or II, as seen in non-conventional toxins and long-chain neurotoxins [9]. The conserved cysteine residues, along with invariant residues like Tyr25 and Phe27, contribute to proper folding [9]. Structural variations occur in the length and conformation of the loops, with some toxins having longer C-terminal or N-terminal extensions [9].

Snake Venom Metalloproteinases (SVMPs)

SVMPs are zinc-dependent enzymes classified into three primary structural categories based on their domain composition [11] [12]:

- P-I SVMPs (20-30 kDa) contain only a metalloproteinase (M) domain [11] [12]

- P-II SVMPs (30-60 kDa) contain metalloproteinase and disintegrin domains [11] [12]

- P-III SVMPs (60-100 kDa) contain metalloproteinase, disintegrin-like, and cysteine-rich domains [11] [12]

The catalytic M domain features a conserved zinc-binding sequence (HEXXHXXGXXH) followed by a "Methionine-turn" motif, with the active site zinc ion coordinated by three histidine residues within this sequence [11] [12]. The P-III class shows the greatest structural diversity due to proteolytic cleavage, repeated domain loss, and presence of ancillary domains [11].

Table 2: SVMP Classification and Functional Properties

| SVMP Class | Domains Present | Molecular Weight | Representative Activities |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-I | Metalloproteinase | 20-30 kDa [11] [12] | Hemorrhage, fibrin(ogen)olysis, apoptosis [11] |

| P-II | Metalloproteinase, Disintegrin | 30-60 kDa [11] [12] | Hemorrhage, platelet aggregation inhibition [11] |

| P-III | Metalloproteinase, Disintegrin-like, Cysteine-rich | 60-100 kDa [11] [12] | Hemorrhage, prothrombin activation, inflammation [11] |

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2s) and CRISPs

While this review focuses on the structural prediction of 3FTxs and SVMPs, PLA2s and CRISPs represent additional important toxin families. PLA2s exhibit both neurotoxic and cytotoxic properties through their ability to disrupt plasma membranes [10]. CRISPs, though not detailed in the available search results, constitute another significant toxin family in snake venoms. The structural prediction challenges for these families parallel those discussed for 3FTxs and SVMPs.

Experimental Validation of Computational Predictions

De Novo Design of 3FTx Inhibitors

Recent advances in deep learning methods have enabled the de novo design of proteins to bind and neutralize 3FTxs [4]. In a landmark study, researchers used RFdiffusion to design binding proteins targeting both short-chain and long-chain α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins from the 3FTx family [4]. The designed proteins exhibited remarkable thermal stability (Tm > 78°C for SHRT and >95°C for LNG) and high binding affinity (Kd values of 0.9 nM for SHRT against short-chain neurotoxins and 1.9 nM for LNG against α-cobratoxin) [4].

X-ray crystallography confirmed near-atomic-level agreement between the computational models and experimental structures, with root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) values of 1.04 Å for SHRT and 0.42 Å for LNG [4]. The designed binders effectively neutralized 3FTxs in vitro and protected mice from lethal neurotoxin challenge, demonstrating the power of accurate structural prediction for therapeutic development [4].

Structural Characterization of Hemachatoxin

The isolation and characterization of hemachatoxin, a novel 3FTx from Hemachatus haemachatus venom, provides a case study in experimental structure validation [9]. Researchers determined the complete amino acid sequence through Edman degradation and mass spectrometry (calculated mass 6836.4 Da, experimental mass 6835.68±0.94 Da), then solved the crystal structure at 2.43 Å resolution using molecular replacement with Naja nigricollis toxin-γ coordinates as a search model [9].

The structure revealed the characteristic three-finger fold with four conserved disulfide bonds and six anti-parallel β-strands forming two β-sheets [9]. Analysis of B factors indicated flexibility in loop II, suggesting conformational adaptability during membrane interaction [9]. This detailed experimental characterization provides valuable validation data for computational predictions of 3FTx structures.

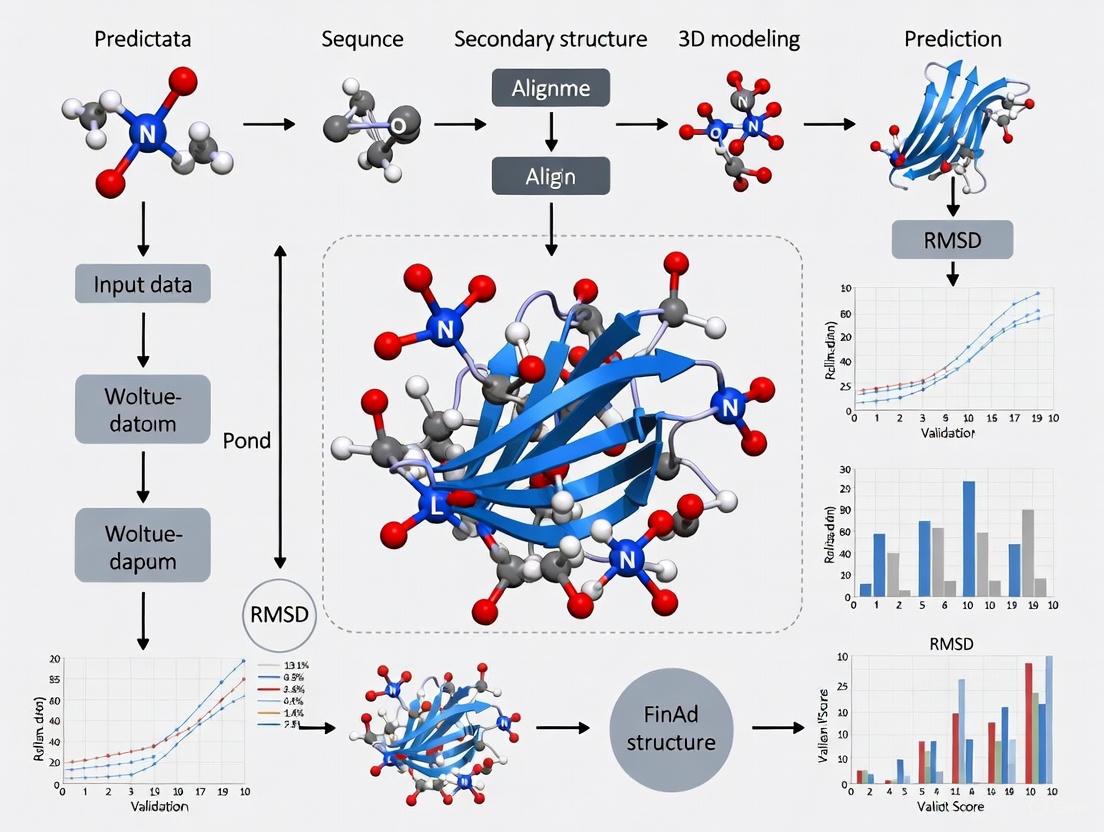

Figure 1: Workflow for Computational Design and Experimental Validation of 3FTx Inhibitors

Research Reagent Solutions for Toxin Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Toxin Characterization

| Reagent / Method | Specific Application | Key Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | 3D structure determination | Provides atomic-resolution structures for validation of computational predictions [9] [14] |

| Cryo-EM | Structural analysis of large complexes | Enables structure determination of toxin complexes without crystallization [15] |

| Liquid Chromatography Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) | Venom proteomics and toxin identification | Identifies and quantifies toxin components in complex venoms [10] |

| Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) / Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) | Binding affinity measurements | Quantifies binding kinetics between toxins and designed inhibitors [4] |

| Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectroscopy | Protein secondary structure and stability | Assesses thermal stability of designed binding proteins [4] |

| Edman Degradation | Protein sequencing | Determines amino acid sequences of purified toxins [9] |

| Yeast Surface Display | Binder screening | Identifies high-affinity binders from designed libraries [4] |

The integration of computational protein design with experimental structural biology has created new opportunities for understanding and neutralizing snake venom toxins. The successful de novo design of 3FTx-binding proteins demonstrates how accurate structure prediction can generate potent inhibitors with therapeutic potential [4]. Similarly, detailed structural characterization of toxins like hemachatoxin and various SVMPs provides essential validation data for improving prediction algorithms [9] [11] [12]. As these methods continue to advance, they promise to accelerate the development of safer, more effective treatments for snakebite envenoming while providing fundamental insights into protein structure-function relationships.

Why Venom Toxins Are Challenging Targets for Structure Prediction

The accurate prediction of protein three-dimensional structures is a cornerstone of modern biochemistry, critical for understanding function and guiding therapeutic development. Within this field, snake venom toxins represent a particularly challenging class of proteins for computational modeling. These toxins, which include diverse families such as three-finger toxins (3FTxs), phospholipases A2 (PLA2s), and snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs), have evolved complex structural features that often defy conventional prediction methods [16]. The limitations of current computational tools against these toxins highlight significant gaps in our understanding of protein-biomembrane interactions and reveal critical dependencies on experimental structural data for training algorithms.

This analysis examines the specific molecular characteristics that make venom toxins difficult to model, compares the performance of various structure prediction platforms on these challenging targets, and details experimental methodologies for validation. By examining both successful applications and notable failures in venom toxin modeling, this guide provides researchers with a framework for assessing the reliability of computational predictions in toxinology and related fields.

Molecular Complexity of Venom Toxins

Snake venom toxins possess unique structural and functional properties that collectively contribute to their challenging nature for prediction algorithms. These difficulties arise from several interconnected factors:

Disulfide Bond Complexity: Many venom toxins, including three-finger toxins and phospholipases B, are stabilized by intricate disulfide bond networks. For instance, SVPLBs from Bothrops moojeni contain five conserved cysteine residues in their mature form, four of which form two disulfide bonds (Cys88–Cys500 and Cys499–Cys523) that are critical for structural integrity [17]. These cross-links create unique topological constraints that are difficult to predict accurately from sequence alone.

Membrane Interaction Mechanisms: Perhaps the most significant challenge lies in predicting how cytotoxins and phospholipases interact with biological membranes. The molecular basis of membrane disruption remains incompletely understood, and current datasets severely underrepresent protein-lipid interactions [18]. This knowledge gap directly impacts prediction accuracy for toxins like three-finger cytotoxins, which exert toxicity through membrane disruption rather than specific receptor binding [4].

Conformational Flexibility: Many toxins exhibit significant structural plasticity, adopting different conformations in various environments. Deep learning-based exploration of venom-encrypted peptides has revealed that many antimicrobial candidates transition from flexible conformations in solution to α-helical structures in membrane-mimicking environments [2], a dynamic behavior that static structure prediction struggles to capture.

Evolutionary Rapid Diversification: Venom toxins evolve under strong positive selection pressure, resulting in sequences that are highly variable yet maintain conserved structural folds. This creates a challenge for homology-based methods, as even toxins with similar structures may share limited sequence identity [16].

Table 1: Key Challenging Features of Major Snake Venom Toxin Families

| Toxin Family | Representative Toxins | Key Structural Challenges | Impact on Prediction Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Three-Finger Toxins (3FTx) | α-neurotoxins, cytotoxins | Multistranded β-structure with three extended loops, conserved disulfide bridges [4] | High accuracy for neurotoxins targeting specific receptors; poor for cytotoxins targeting membranes [18] |

| Phospholipases B (PLB) | PLB_Bm from Bothrops moojeni | Four-layer αββα sandwich core, 18 β-strands, 17 α-helices, N-terminal nucleophile aminohydrolase fold [17] | Homology modeling possible with 70% identity templates, but membrane interaction sites difficult to predict |

| Snake Venom Nerve Growth Factors | sNGF from Daboia russelii, Naja naja | Dimeric structure, extensive disulfide bonds, protease resistance [19] | Enhanced stability factors complicate dynamics predictions; coevolutionary analysis needed for interface predictions |

Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods

Various computational approaches have been applied to venom toxin structure prediction, with markedly different success rates across toxin families and functional classes. The performance disparity highlights how methodological limitations affect practical applications in antivenom development and therapeutic discovery.

Success with Neurotoxins Versus Failure with Cytotoxins

Recent research demonstrates a striking contrast in prediction accuracy between different three-finger toxin subfamilies. AI-based approaches have successfully designed inhibitory proteins against α-neurotoxins, which function through specific receptor interactions. The RFdiffusion software generated designs that formed extensive backbone hydrogen bonds with target neurotoxins, achieving remarkable binding affinity (Kd = 0.9 nM for short-chain α-neurotoxin binder SHRT) and providing complete protection in mouse models [4]. The successful application involved:

- Using RFdiffusion conditioned on secondary structure and block adjacency tensors to generate backbones forming extended β-sheets with target neurotoxins

- Applying ProteinMPNN for sequence design on the generated backbones

- Filtering designs using AlphaFold2 and Rosetta metrics

- Experimental validation through yeast surface display and biophysical methods (BLI, SPR)

- Structural verification via X-ray crystallography (2.58 Å resolution for SHRT-ScNtx complex) [4]

In stark contrast, the same computational pipeline failed to produce effective inhibitors for cytotoxins from the same structural family. Despite creating designs with high binding affinity in vitro, these inhibitors showed no protective effect in mouse models against toxin-induced skin lesions [18]. This failure underscores a fundamental limitation: current AI tools like AlphaFold and Rosetta excel at predicting protein-protein interactions but perform poorly with protein-lipid interactions [18].

Homology Modeling Limitations and Successes

Homology modeling remains valuable for toxins with suitable templates, though with significant limitations. For SVPLBs, modeling using phospholipase B-like protein from Bos taurus (70% sequence identity) as a template produced viable structures validated through PROCHECK, ERRAT, and Verif3D [17]. However, this approach revealed substantial variations in surface charge distribution, active site cavity volume, and depth across homologs—features critical for understanding function and developing inhibitors that are poorly captured by modeling [17].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Computational Methods on Venom Toxins

| Method | Best For | Key Limitations | Experimental Validation Required |

|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion + ProteinMPNN | De novo design of protein-protein inhibitors (e.g., against α-neurotoxins) [4] | Fails for membrane-disrupting toxins; requires extensive experimental screening | Essential (yeast display, BLI/SPR, X-ray crystallography, in vivo models) |

| AlphaFold2 | Structure prediction of soluble toxins, complex prediction [16] | Poor performance on protein-lipid interactions; limited by training dataset gaps [18] | Recommended, especially for novel folds or membrane-associated toxins |

| Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Understanding binding stability (e.g., sNGF-TrkA interactions) [19] | Computationally intensive; limited timescales; force field inaccuracies for non-standard interactions | Validation through binding assays, functional studies |

| Homology Modeling | Toxins with high-sequence identity templates (>70%) [17] | Misses subtle structural variations critical for function; template availability limited | Necessary, particularly for active site characterization |

Experimental Validation Workflows

Rigorous experimental validation is essential for confirming computational predictions of venom toxin structures, particularly given the known limitations of in silico methods. The following protocols represent state-of-the-art approaches for verifying predicted structures and interactions.

Structural Determination and Binding Assays

The successful development of neurotoxin inhibitors combined computational design with extensive experimental validation through this comprehensive workflow:

For binding characterization, Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) and Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) provide quantitative measurements of toxin-inhibitor interactions. The standard protocol involves:

- Immobilization: Toxins are immobilized on biosensor chips (BLI) or sensor surfaces (SPR) via amine coupling

- Association: Serial dilutions of designed binders are flowed over the surface at 25°C in HBS-EP buffer

- Dissociation: Buffer without binder is flowed to monitor complex dissociation

- Analysis: Binding curves are fitted to 1:1 binding models to calculate kinetic parameters (Kd, kon, koff) [4]

Functional and In Vivo Validation

Beyond structural and binding studies, functional assays are critical for confirming that designed inhibitors actually neutralize toxin activity:

In Vitro Neutralization: For neurotoxins, cell-based assays measuring protection against acetylcholine receptor blockade are essential. Cultured neuroblastoma cells expressing muscle-type nAChRs are pre-treated with toxins followed by addition of designed inhibitors, with viability and receptor function as endpoints [4].

In Vivo Protection Models: Mouse challenge models provide the most clinically relevant validation. For neurotoxins, mice are injected with lethal doses of toxin (LD99) concurrently with or followed by inhibitor administration. Survival, symptom progression (paralysis, respiratory distress), and histological analysis of tissues provide comprehensive efficacy data [4].

The critical importance of functional validation is highlighted by the cytotoxin inhibitor failure—despite excellent binding metrics in vitro (Kd in nM range), the inhibitors provided no protection against tissue damage in mouse models [18].

Research Reagent Solutions

Advancing venom toxin structure prediction requires specialized reagents and computational resources. The table below details essential research tools for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Venom Toxin Structure Prediction

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function/Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Computational Platforms | RFdiffusion [4], AlphaFold2 [16], Rosetta [16], APEX [2] | De novo protein design, structure prediction, antimicrobial peptide mining | Specialized for different interaction types (protein-protein vs. protein-lipid) |

| Structural Databases | UniProt [20] [19], VenomZone [20] [2], ConoServer [2], ArachnoServer [2] | Source of toxin sequences, structures, and functional annotations | Varying coverage of different venomous species; integration challenges |

| Experimental Validation | Yeast Surface Display [4], BLI/SPR [4], X-ray Crystallography [4] | Binding affinity measurement, structural verification | High-throughput screening (yeast display) vs. high-precision (crystallography) |

| Specialized Datasets | DBAASP [2], ISOB [2], Custom venom proteomics datasets [16] | AMP comparison, species-specific toxins, training machine learning models | Variable quality; require curation and standardization |

The structural prediction of venom toxins remains a formidable challenge, with success heavily dependent on toxin class and the nature of its biological interactions. Current AI-driven methods have demonstrated remarkable capabilities for designing inhibitors against toxin-receptor interactions but show significant limitations for toxins targeting lipid membranes. This disparity underscores fundamental gaps in our understanding of protein-membrane interactions and highlights the critical importance of comprehensive experimental validation.

The field requires advances in several key areas: improved representation of membrane-associated proteins in training datasets, development of specialized algorithms for protein-lipid interactions, and standardized validation protocols that include functionally relevant assays. As computational methods continue to evolve, integrating multiple approaches—from deep learning-based design to molecular dynamics simulations—will likely provide the most productive path forward for overcoming the unique challenges posed by venom toxins.

The Critical Role of Genomic and Transcriptomic Data in Foundation Building

The field of toxinology has been transformed by the integration of large-scale biological data. Genomic and transcriptomic information now provides the essential foundation for understanding the complex composition and evolution of snake venoms, which are primarily composed of numerous proteins and peptides. This data-driven approach has become particularly critical for validating and advancing computational protein structure prediction tools, which rely on high-quality sequence information to model toxin structures with atomic-level precision. The shift from traditional, low-throughput experimental methods to a bioinformatics-guided framework has accelerated the pace of discovery, enabling researchers to move from venom characterization to therapeutic development with unprecedented speed and accuracy. This comparison guide examines how different computational approaches perform when grounded in comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic data, with a specific focus on applications in snake venom research.

Performance Comparison of Structure Prediction Tools on Venom Toxins

Recent studies have systematically evaluated how well modern computational tools predict the structures of snake venom toxins, which often lack experimental structures due to their complexity and the challenges in isolation and crystallization.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Protein Structure Prediction Tools on Snake Venom Toxins

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Performance on Small Toxins (e.g., 3FTx) | Performance on Large, Complex Toxins (e.g., SVMPs) | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Monomer structure prediction | High accuracy [7] | Moderate accuracy [7] | Struggles with flexible loops [7] |

| ColabFold | Monomer structure prediction | Slightly lower than AF2 [7] | Moderate accuracy [7] | Computationally intensive [7] |

| AlphaFold-Multimer | Protein complex prediction | Not specifically evaluated | Not specifically evaluated | Lower accuracy than monomer predictions [21] |

| DeepSCFold | Protein complex prediction | Superior for antibody-antigen interfaces [21] | Improved TM-score over other methods [21] | Requires multiple sequence alignments [21] |

The table above highlights a critical finding from a 2024 Toxicon study which demonstrated that while machine-learning tools can successfully predict toxin structures, their performance varies significantly based on toxin size and complexity [7]. All tools face challenges with intrinsically disordered regions common in venom proteins, particularly flexible loops that may be crucial for functional activity.

For protein complexes common in venom systems, newer methods like DeepSCFold have shown remarkable improvements. In benchmark testing, DeepSCFold achieved an 11.6% improvement in TM-score compared to AlphaFold-Multimer on CASP15 multimer targets, and enhanced the success rate for predicting antibody-antigen binding interfaces by 24.7% over AlphaFold-Multimer [21]. This demonstrates how specialized tools leveraging sequence-derived structural complementarity can overcome limitations of more general approaches.

Experimental Protocols for Validation Studies

Protocol for Benchmarking Prediction Tools on Toxin Targets

A comprehensive comparative study published in 2024 established a standardized protocol for evaluating structure prediction tools on challenging toxin targets [7]:

- Dataset Curation: Compile a diverse set of over 1,000 snake venom toxin sequences with no experimentally determined structures, representing major toxin families (3FTxs, SVMPs, PLA2s, etc.).

- Model Generation: Process all sequences through multiple prediction tools (AlphaFold2, ColabFold, Modeller) using standardized computing resources.

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate predictions using multiple metrics including per-residue confidence scores (pLDDT), root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) from reference structures when available, and visual inspection of functionally important regions.

- Functional Validation: Compare predicted structures with known functional data, including receptor binding sites and enzymatic active sites, to assess biological relevance beyond structural accuracy.

This protocol revealed that while global structures were often well-predicted, local regions corresponding to functional domains showed variation between tools, emphasizing the need for multi-tool consensus approaches.

Protocol for De Novo Binder Design Against Venom Toxins

A groundbreaking 2025 Nature study established a protocol for designing synthetic proteins to neutralize snake venom toxins using structure prediction and design tools [4]:

- Target Selection: Focus on three-finger toxin (3FTx) subfamilies (short-chain α-neurotoxins, long-chain α-neurotoxins, and cytotoxins) responsible for severe envenoming pathology.

- Computational Design: Use RFdiffusion to generate protein backbones conditioned on binding to specific toxin epitopes, followed by ProteinMPNN for sequence design.

- In Silico Screening: Filter designs using AlphaFold2 predictions and interface metrics, selecting top candidates for experimental testing.

- Experimental Validation:

- Affinity Measurement: Validate binding using surface plasmon resonance (SPR) and bio-layer interferometry (BLI).

- Structural Verification: Determine crystal structures of toxin-binder complexes to validate computational models.

- Functional Neutralization: Test neutralization capacity in vitro (e.g., toxin receptor binding assays) and in vivo (mouse protection models).

This protocol yielded remarkable results, with designed binders achieving picomolar to nanomolar affinities (e.g., 0.9 nM for short-chain neurotoxin binder SHRT) and demonstrating potent toxin neutralization in animal models [4] [22]. The close agreement between computational models and experimental structures (RMSDs of 0.42-1.04 Å) strongly validated the structure prediction approach.

Visualization of Research Workflows

Diagram 1: Integrated workflow for venom research showing how genomic and transcriptomic data foundation enables downstream applications.

Diagram 2: AI-driven pipeline for antivenom development showing the closed-loop design process.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Venom Genomics and Structure Prediction

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Application in Toxin Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Databases | AlphaSync [23] | Provides continuously updated predicted protein structures | Ensures researchers work with current structural models; addressed backlog of 60,000 outdated structures |

| Structure Prediction Tools | AlphaFold2, ColabFold [7] | Predicts 3D structures from amino acid sequences | Models toxin structures when experimental data unavailable; superior for small toxins like 3FTxs |

| Complex Structure Prediction | DeepSCFold [21] | Predicts protein complex structures using sequence-derived complementarity | Models toxin-receptor interactions; improves antibody-antigen interface prediction by 24.7% |

| De Novo Design Tools | RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN [4] [22] | Generates novel protein binders for specific targets | Designs toxin-neutralizing proteins; achieved 0.9 nM affinity for α-neurotoxins |

| Transcriptomic Resources | Venom gland transcriptome databases [24] [25] | Catalog toxin gene expression profiles | Identifies full toxin repertoire; reveals heterogeneity in venom production |

| Validation Resources | SAbDab [21] | Database of antibody structures | Benchmark for antibody-toxin complex predictions |

The integration of genomic and transcriptomic data has fundamentally transformed snake venom research, creating a robust foundation for validating and applying protein structure prediction tools. Performance comparisons clearly demonstrate that while general-purpose tools like AlphaFold2 provide excellent starting points, specialized methods like DeepSCFold offer significant advantages for modeling the complex protein interactions relevant to toxin neutralization. The experimental success of de novo designed toxin binders - achieving near-atomic accuracy and potent neutralization in vivo - provides compelling validation of this integrated approach. As resources like AlphaSync ensure ongoing data currency, and tools continue to evolve, the research community is positioned to accelerate the development of next-generation therapeutics for snakebite and other toxin-mediated conditions.

A Practical Guide to Structure Prediction Tools and Workflows for Venom Research

In the field of structural biology, accurately predicting protein three-dimensional (3D) structures from amino acid sequences is crucial for understanding function and facilitating drug discovery. This is particularly relevant for snake venom toxins, which are challenging targets due to their flexibility, limited homologous sequences, and the scarcity of experimentally determined structures for validation. This guide objectively compares the performance of four computational tools—AlphaFold2, ColabFold, Modeller, and RFdiffusion—within the specific context of snake venom toxin research, providing experimental data and protocols to inform scientists in their selection process.

Performance Comparison on Snake Venom Toxins

A 2024 comparative study in Toxicon evaluated AlphaFold2, ColabFold, and Modeller on over 1,000 snake venom toxins for which no experimental structures existed [7]. The following table summarizes their key performance metrics.

Table 1: Performance of structure prediction tools on snake venom toxins

| Tool | Overall Performance | Performance on Small Toxins (e.g., 3FTxs) | Performance on Large Toxins (e.g., SVMPs) | Challenges and Limitations | Computational Intensity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) | Best performance across all assessed parameters [7] | Superior prediction accuracy [7] | Struggled more compared to small toxins [7] | Struggles with flexible loop regions and intrinsic disorder [7] | High [7] |

| ColabFold (CF) | Slightly worse than AF2, but still strong [7] | High prediction accuracy [7] | Struggled more compared to small toxins [7] | Struggles with flexible loop regions and intrinsic disorder [7] | Less intensive than AF2 [7] |

| Modeller | Lower performance compared to AF2 and CF [7] | Not specified | Not specified | Struggles with flexible loop regions and intrinsic disorder [7] | Not specified |

| RFdiffusion | Not directly tested in this study, but used successfully for de novo binder design against toxins [4] | Successfully used to design binders for small 3FTx neurotoxins [4] | Not specified | Not primarily a prediction tool; used for generative binder design [4] | Not specified |

The study concluded that while all tools performed well in predicting stable functional domains, they consistently struggled with regions of intrinsic disorder, such as flexible loops and propeptide regions, which are common in toxins [7]. Therefore, researchers should exercise caution when interpreting predictions of these dynamic elements.

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

The tools compared here encompass two main types of computational approaches: protein structure prediction (deducing the structure of a given sequence) and de novo binder design (creating new proteins that bind to a target of interest). RFdiffusion falls into the latter category. Below are detailed methodologies for key experiments cited in the results.

Comparative Prediction of Snake Venom Toxin Structures

The protocol from the 2024 Toxicon study provides a direct comparison of AF2, ColabFold, and Modeller [7].

- Objective: To evaluate the accuracy of multiple structure prediction tools on a large set of snake venom toxins without experimentally-solved structures.

- Dataset: Over 1,000 snake venom toxin sequences from protein families such as three-finger toxins (3FTxs) and snake venom metalloproteinases (SVMPs). Sequences were collected from UniProt and RefSeq, with redundancy reduced at a threshold of 80% sequence identity [7].

- Methodology:

- Input Sequences: The same toxin sequences were processed independently by AlphaFold2, ColabFold, and Modeller.

- Structure Prediction:

- AlphaFold2: Searches large sequence databases (e.g., UniRef, BFD, MGnify) with HHblits and HMMer to build multiple sequence alignments (MSAs) as input for its deep neural network [26].

- ColabFold: Utilizes the MMseqs2 algorithm for drastically faster (40-60x) MSA generation against similar databases, including its own ColabFoldDB, before feeding features into a modified AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold network [26].

- Modeller: A comparative modeling tool that uses known protein structures as templates to model the structure of a target sequence. The specific version and template database used were not detailed in the study [7].

- Analysis: The predicted models were assessed on parameters of accuracy, which likely included metrics like RMSD (Root Mean Square Deviation) and confidence scores, though the specific metrics are not listed in the search results [7].

Workflow for predicting toxin structures

De Novo Binder Design against Toxins using RFdiffusion

A landmark 2025 study in Nature detailed the use of RFdiffusion to design proteins that neutralize lethal snake venom toxins [4]. This demonstrates an advanced application of structure prediction models for therapeutic development.

- Objective: To computationally design de novo proteins that bind and neutralize three-finger toxins (3FTxs) like α-neurotoxins and cytotoxins.

- Targets: A consensus short-chain α-neurotoxin (ScNtx) and the native long-chain α-neurotoxin α-cobratoxin [4].

- Methodology:

- Conditioned Generation: The RFdiffusion network was conditioned on the target toxin's structure. For α-neurotoxins, the generation was guided to form extended β-sheets with exposed edge β-strands on the toxin. For cytotoxins, "hotspot" residues were defined on the three-finger loops to direct binding [4].

- Sequence Design: Generated protein backbones were assigned sequences using ProteinMPNN, a deep learning-based sequence design tool [4].

- Filtering & Selection: Designed proteins were filtered using a combination of:

- Experimental Validation: Top candidates were tested via:

- Yeast Surface Display: For initial binding confirmation.

- Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) / Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): To measure binding affinity (Kd).

- X-ray Crystallography: To verify that the designed complex matched the computational model (achieving RMSD as low as 0.42 Å) [4].

- In Vitro and In Vivo Neutralization Assays: To confirm protective efficacy against venom toxicity [4].

Workflow for designing toxin binders

Advanced Workflows and Emerging Tools

BindCraft: An Enhanced ColabFold Pipeline for Binder Design

BindCraft is a protocol built upon ColabFold's implementation of AlphaFold2 Multimer (AF2M) to improve de novo binder design [27] [28].

- How it Works:

- It starts with a random amino acid sequence for the binder.

- AF2M co-folds this random sequence with the target protein.

- An iterative optimization loop begins, using gradient-based backpropagation through the AF2M network. This process suggests sequence changes that improve scores for binding confidence, interface interaction strength, and other metrics.

- The final optimized sequence is refined with ProteinMPNN and filtered again with AF2M to ensure quality and solubility [27].

- Performance: In tests on 10 targets, BindCraft produced binders with sub-nanomolar affinity and achieved significantly better experimental hit rates than many other de novo design methods [27]. It was also the winning method in an EGFR binder design competition, producing a binder with a Kd of 4.91e-7 M [28].

AfCycDesign: Adapting ColabFold for Cyclic Peptides

Cyclic peptides are a promising therapeutic modality. AfCycDesign is a modification of the AlphaFold2/ColabDesign framework that introduces a custom cyclic offset to the model's relative positional encoding, enabling accurate structure prediction and de novo design of cyclic peptides [29]. In tests, it predicted cyclic peptide structures with a median RMSD of 0.8 Å to experimental structures and was successfully used to design binders against targets like MDM2 and Keap1 [29].

Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Toxinology

The following table details key computational tools and databases essential for conducting the experiments described in this guide.

Table 2: Key research reagents and tools for computational toxin research

| Item Name | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2 | Software | Highly accurate protein structure prediction from sequence using MSAs and deep learning [26] [7]. |

| ColabFold | Software | Accessible, accelerated protein structure prediction combining MMseqs2 fast homology search with AF2 or RoseTTAFold [26] [7]. |

| RFdiffusion | Software | Generative AI model for creating novel protein structures and binders conditioned on a target [4]. |

| Modeller | Software | Comparative protein structure modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints, useful when templates are available [7]. |

| ProteinMPNN | Software | Neural network for designing amino acid sequences that fold into a given protein backbone structure [27] [4]. |

| UniProt/RefSeq | Database | Source of canonical protein sequences for collecting toxin and non-toxin datasets [7] [30]. |

| ColabFoldDB | Database | Custom environmental database for MSA generation, combining BFD/MGnify with eukaryotic/metagenomic sequences [26]. |

| RoseTTAFold | Software | A deep learning-based protein structure prediction tool, similar to AlphaFold2 [26]. |

| Rosetta | Software Suite | A comprehensive suite for macromolecular modeling, used for energy scoring and refinement in design protocols [4] [29]. |

Workflow for de Novo Design of Toxin-Neutralizing Proteins

Snakebite envenoming is a neglected tropical disease claiming over 100,000 lives annually, with current antivenom treatments relying on century-old methods of animal immunization that yield variable efficacy and potential adverse effects [4] [31]. The emergence of artificial intelligence (AI) and deep learning methods has revolutionized protein science, shifting the paradigm from structure prediction to de novo creation of therapeutic proteins with optimized properties [32]. This guide examines the workflow for designing toxin-neutralizing proteins, comparing computational tools and experimental methods while contextualizing performance within snake venom toxin research.

Comparative Analysis of Computational Protein Design Tools

Tool Performance Characteristics

AI-driven platforms have demonstrated remarkable capabilities in generating novel protein structures, though their performance varies significantly across different design challenges.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Protein Design and Prediction Platforms

| Tool Name | Primary Function | Strengths | Limitations | Reported Success Rate/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion | De novo protein design | Creates novel proteins with high stability and affinity; enables β-strand pairing for toxin neutralization [4] | Requires experimental validation; may generate false positives [32] | Designed binders with Kd values of 0.9-271 nM for various 3FTx subfamilies [4] |

| AlphaFold2 (AF2) | Structure prediction | Superior accuracy for well-characterized proteins and functional domains; best overall performance [7] [33] | Struggles with flexible loops and disordered regions [7] [33] | Highest performance across assessed parameters for toxin structure prediction [7] |

| ColabFold (CF) | Structure prediction | Slightly worse than AF2 but computationally less intensive [7] [33] | Similar limitations with flexible regions as AF2 [7] | Near-AF2 performance with reduced computational requirements [7] |

| ProteinMPNN | Sequence design | Robust sequence optimization for designed backbones [4] [31] | Dependent on quality of input backbone structures | Critical for achieving stable, expressible designs [4] |

Tool Selection Considerations

For snake venom toxins specifically, a multitool prediction strategy consistently outperforms single-tool approaches [8]. The integration of structural and sequence-based models is particularly important when working with toxins lacking experimental structures, as all tools struggle with regions of intrinsic disorder such as loops and propeptide regions [7] [33]. The workflow typically employs RFdiffusion for backbone generation, ProteinMPNN for sequence design, and AlphaFold2 for initial structural validation [4] [31].

Experimental Validation Workflow

Quantitative Assessment of Designed Proteins

The efficacy of de novo designed toxin-neutralizing proteins has been rigorously validated through multiple experimental approaches, yielding compelling quantitative data on their performance.

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics of Designed Toxin-Binding Proteins

| Designed Binder | Target Toxin | Binding Affinity (Kd) | Thermal Stability (Tm) | Structural Validation | Neutralization Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SHRT | Short-chain α-neurotoxin (consensus) | 0.9 nM (SPR) [4] | 78°C [4] | X-ray crystallography (1.04 Å RMSD) [4] | Protection in lethal mouse challenge [4] |

| LNG | α-cobratoxin (long-chain neurotoxin) | 1.9 nM (SPR) [4] | >95°C [4] | X-ray crystallography (0.42 Å RMSD over design) [4] | Protection in lethal mouse challenge [4] |

| CYTX | Cytotoxin (consensus) | 271 nM (SPR) [31] | High solubility, monomeric [31] | Not specified | Neutralized whole venoms (N. pallida, N. nigricollis) [31] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Binding Affinity Measurement (SPR/BLI)

Purpose: Quantify binding kinetics between designed proteins and toxin targets.

- Immobilization: Toxins or designed binders are immobilized on sensor chips (SPR) or biosensor tips (BLI)

- Association Phase: Introduced binding partners at varying concentrations in solution phase

- Dissociation Phase: Monitored complex dissociation in buffer-only flow

- Data Analysis: Determined dissociation constants (Kd) by fitting binding curves to 1:1 binding models

- Key Equipment: Surface plasmon resonance instruments (SPR) or bio-layer interferometry (BLI) systems [4] [31]

Structural Validation (X-ray Crystallography)

Purpose: Verify computational models with experimental structural data.

- Crystallization: Designed proteins (apo or complexed with toxins) crystallized using vapor diffusion methods

- Data Collection: X-ray diffraction data collected at synchrotron facilities

- Structure Solution: Molecular replacement or experimental phasing methods

- Model Validation: Computational models compared to electron density maps, RMSD calculated [4]

In Vitro Neutralization Assays

Purpose: Assess functional efficacy of designed binders.

- Cell Viability Assays: Luminescent assays measuring protection against cytotoxin-induced cell death

- nAChR Binding Interference: Measured prevention of neurotoxin binding to nicotinic acetylcholine receptors

- Venom Neutralization: Tested against whole venoms with high target toxin content [4] [31]

In Vivo Protection Studies

Purpose: Evaluate protective efficacy in biologically relevant systems.

- Animal Model: Mice challenged with lethal doses of neurotoxins

- Dosing Regimens: Pre-incubation of toxin with binder; post-challenge administration (e.g., 15 minutes after toxin)

- Endpoint Monitoring: Survival tracked over specified period (e.g., up to two weeks)

- Molar Ratios: Tested various toxin:binder ratios (e.g., 1:10) [4] [34]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Toxin-Neutralizing Protein Design

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Design Platforms | RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN, AlphaFold2 [4] [7] | De novo backbone generation, sequence design, and structural validation |

| Expression Systems | E. coli recombinant expression [4] [31] | High-yield production of designed proteins; cost-effective manufacturing |

| Binding Affinity Assays | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) [4] | Quantitative measurement of protein-toxin binding kinetics and affinity |

| Structural Biology Tools | X-ray crystallography, Size Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) [4] | Experimental structure determination and validation of computational models |

| Stability Assessment | Circular Dichroism (CD) melting experiments [4] | Measurement of thermal stability and folding properties |

| In Vitro Neutralization | Luminescent cell viability assays, nAChR binding interference [4] [31] | Functional assessment of toxin neutralization in cellular systems |

| In Vivo Models | Mouse lethal challenge models [4] [34] | Preclinical validation of protective efficacy in whole organisms |

Workflow Visualization

Computational Design and Validation Workflow

Experimental Validation Pipeline

The workflow for de novo design of toxin-neutralizing proteins represents a transformative approach to antivenom development, leveraging AI-driven computational design integrated with rigorous experimental validation. This methodology has demonstrated remarkable success in creating stable, high-affinity binders against challenging three-finger toxin targets, with binding affinities in the nanomolar range and proven efficacy in protecting against lethal toxin challenges [4] [34]. As the field advances, the integration of multiple prediction tools, careful attention to flexible regions in toxin structures, and systematic experimental validation will be crucial for developing the next generation of antivenom therapeutics that are safer, more effective, and more accessible than current options [7] [8] [35].

Application in Epitope Mapping for Antivenom Development (B-cell and T-cell)

Snakebite envenomation remains a significant global health challenge, classified as a Category A neglected tropical disease by the World Health Organization [36]. Traditional antivenom production, which relies on animal immunization with whole venom, faces considerable limitations including batch variability, limited cross-reactivity, and the risk of adverse immune reactions [8]. Epitope mapping—the process of identifying specific regions on antigens recognized by immune cells—has emerged as a transformative approach for developing safer, more effective, and rationally designed antivenoms. Within this context, validating protein structure prediction tools for snake venom toxins is paramount, as accurate structural models provide the foundation for reliable epitope identification and characterization.

The immune response to snake venom toxins involves both B-cell epitopes (BCEs), which are regions directly recognized by B-cell receptors or secreted antibodies, and T-cell epitopes (TCEs), which are peptides presented by major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecules to activate T-cell help [37] [8]. While BCEs can be linear (continuous sequences) or conformational (discontinuous residues brought together by protein folding), most B-cell epitopes are thought to be conformational, necessitating accurate structural information for their identification [38]. Understanding both epitope types is crucial for developing effective antivenoms, as T-cell help is essential for generating high-affinity, long-lasting antibody responses against venom toxins [37].

Computational Approaches for Epitope Prediction

Computational immunoinformatics has revolutionized epitope prediction by enabling rapid, large-scale screening of venom toxins, significantly reducing reliance on venom immunizations and accelerating the discovery process [8]. These methods leverage algorithms trained on physicochemical properties, structural features, and machine learning to identify potential immunogenic regions.

Comparison of Computational Prediction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Computational Epitope Prediction Approaches

| Method Type | Examples | Key Features | Performance Metrics | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sequence-Based BCE Predictors | ABCpred, BepiPred, TEPRF | Uses amino acid propensity scales, hydrophilicity, flexibility; ABCpred employs machine learning | AUC: 0.445-0.538; High false positive rates [39] | Initial screening of linear epitopes |

| Structure-Based BCE Predictors | DiscoTope, ElliPro | Leverages 3D structural data to identify surface-accessible residues | Better for conformational epitopes [38] | Toxins with known or well-predicted structures |

| T-cell Epitope Predictors | NetMHCIIPan, TEPITOPE | Predicts peptide binding to MHC class II molecules | Identifies peptides with T-cell activation potential [37] [36] | Assessing immunogenicity risk and vaccine design |

| Protein Class-Specific Models | Custom decision tree classifier for metalloendopeptidases | Trained on curated epitopes from specific protein families | Lower false positive rate (0.33 vs 0.40-0.58); Improved AUC [39] | Toxins belonging to well-characterized protein families |

| Deep Learning Approaches | Deep-STP | Uses g-gap, natural vector, and Word2Vec features with CNN | Accuracy: 82.00%; Effective for toxin classification [30] | General snake toxin protein identification |

Protein Structure Prediction Tools for Venom Toxins

Accurate structural models are essential for conformational epitope mapping. Recent advances in machine learning-based structure prediction have shown promising results for snake venom toxins, though with important limitations. A 2024 comparative study evaluated three modelling tools on over 1000 snake venom toxin structures [7]:

- AlphaFold2 (AF2) performed best across all assessed parameters, demonstrating remarkable accuracy for small toxins like three-finger toxins (e.g., cytotoxins, neurotoxins).

- ColabFold (CF) scored slightly worse than AF2 but offered computational efficiency advantages.

- All tools struggled with regions of intrinsic disorder, particularly flexible loops and propeptide regions, which are common in larger toxins like Snake Venom Metalloproteinases (SVMPs).

- Predictions were most reliable for functional domains, highlighting the importance of exercising caution when working with toxins lacking experimental structures [7].

These structural predictions enable computational epitope mapping through molecular docking simulations, with studies successfully identifying potential T-cell and B-cell epitopes in cobra venom cytotoxins through computational approaches [36].

Experimental Validation of Predicted Epitopes

Computational predictions require experimental validation to confirm their immunological relevance. Multiple techniques have been developed to characterize epitopes at the molecular level, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

Key Experimental Techniques for Epitope Mapping

Table 2: Experimental Methods for Epitope Validation

| Method | Principle | Epitope Type Detected | Throughput | Key Advantages | Major Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SPOT Synthesis | Cellulose-bound peptide arrays probed with antibodies | Linear B-cell epitopes | High | Economically viable; assesses many peptides simultaneously [40] | Misses conformational epitopes |

| Peptide ELISA | Peptides immobilized on plates for antibody binding | Linear B-cell epitopes | Medium | Fast and cost-effective with high specificity [38] | Limited to linear epitopes only |

| Phage Display | Phage libraries expressing random peptides screened with antibodies | Mainly linear B-cell epitopes | High | Can mimic some conformational epitopes [38] | Biased toward high-affinity binders |

| X-ray Crystallography | Determines 3D structure of antibody-antigen complexes | Conformational B-cell epitopes | Low | Atomic-level resolution of interactions [38] [5] | Technically challenging; requires crystals |

| MELD/LC-MS | Multi-enzymatic limited digestion with mass spectrometry | Linear B-cell epitopes | Medium | Provides sequence-level epitope information [36] | Complex data interpretation |

| LIBRA-seq | Links BCR sequencing to antigen specificity | Both linear and conformational | High | High-throughput; connects sequence to function [38] | Specialized equipment required |

| T-cell Assays (ELISpot, Proliferation) | Measures T-cell activation upon peptide exposure | T-cell epitopes | Medium | Confirms functional immunogenicity [37] | Requires viable immune cells |

Integrated Epitope Mapping Workflows

The most successful epitope mapping strategies combine multiple computational and experimental approaches. The following workflow illustrates a comprehensive strategy for epitope identification and validation in antivenom development:

Case Studies in Epitope-Driven Antivenom Development

Multiepitope Antivenom Against Loxosceles Spider Venom

A landmark study demonstrated the power of epitope mapping for developing broad-spectrum antivenoms. Researchers identified three linear epitopes for Loxosceles astacin-like protease 1 (LALP-1) and two for hyaluronidase (LiHYAL) from Loxosceles intermedia spider venom using SPOT-synthesis technique [40]. These were combined with a previously characterized epitope of sphingomyelinase D (SMase D) to generate a recombinant multiepitopic protein (rMEPLox).

Key findings included:

- rMEPLox was non-toxic and elicited antibodies reactive with multiple Loxosceles species venoms (L. intermedia, L. laeta, L. gaucho, and L. similis)

- Anti-rMEPLox antibodies efficiently neutralized sphingomyelinase, hyaluronidase, and metalloproteinase activities of L. intermedia venom

- The multiepitope approach provided broader protection compared to single-epitope immunogens [40]

This epitope-driven strategy successfully addressed the challenge of venom scarcity for immunization and produced a candidate suitable for both antivenom production and experimental vaccination.

Cobra Venom Cytotoxin Epitope Analysis

A 2023 study addressed the critical challenge of cytotoxin (CTX) neutralization in cobra envenomation. CTX constitutes approximately 70% of cobra venom and is responsible for dermonecrotic symptoms, but exhibits low immunogenicity, making conventional antivenoms ineffective against its toxicity [36].

The research combined:

- Immunoinformatic analyses predicting T-cell and B-cell epitopes

- Molecular docking simulations identifying HLA-B62 as the supertype with greatest binding affinity

- MELD/LC-MS epitope-omics revealing three potential epitope sequences

- Site-directed mutagenesis confirming epitope locations at functional loops

This integrated approach identified four potential epitope sites residing within CTX's functional loops, providing crucial targets for developing CTX-targeted antivenoms [36].

Neutralizing Antibodies Against Snake Venom Metalloproteinases

Research on metalloendopeptidases from Bothrops snake venoms demonstrated that computational predictions could identify epitopes missed by experimental mapping alone. A custom decision tree classifier trained specifically on metalloendopeptidase epitopes achieved a lower false positive rate (0.3266) compared to general prediction tools like ABCpred (0.5752) and BepiPred (0.3961) [39].

Notably, immunization with a computationally predicted epitope that was undetected by SPOT immunoassays successfully induced neutralizing antibody production in mice, demonstrating that computational methods can reveal epitopes with significant therapeutic potential that might be overlooked by standard experimental approaches [39].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Epitope Mapping

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| SPOT Synthesis Kit | Parallel peptide synthesis on cellulose membranes | Mapping linear B-cell epitopes in LALP-1 and LiHYAL [40] |

| HLA Allele Panels | Assessing peptide binding to diverse MHC molecules | T-cell epitope prediction for cytotoxin [36] |

| Peptide ELISA Kits | Measuring antibody binding to synthetic peptides | Validating epitope immunoreactivity [38] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Training custom epitope prediction models | Deep-STP for snake toxin identification [30] |

| Structural Biology Software | Molecular docking and dynamics simulations | HLA-epitope interaction studies [36] |

| Multi-enzymatic Digestion Kits | Sample preparation for epitope-omics | MELD/LC-MS epitope mapping [36] |

Epitope mapping represents a paradigm shift in antivenom development, moving from empirical whole-venom immunization toward rational, targeted approaches. The integration of computational predictions with experimental validation creates a powerful framework for identifying key immunogenic regions on venom toxins. Advances in protein structure prediction, particularly through tools like AlphaFold2, provide increasingly reliable structural models that enhance conformational epitope detection, though challenges remain for flexible regions and larger toxins.

The future of epitope-based antivenom development lies in multi-epitope strategies that incorporate both B-cell and T-cell epitopes from multiple toxins, creating broadly protective and highly specific therapeutics. As computational methods continue to improve and experimental techniques become more sophisticated, epitope-driven approaches promise to revolutionize the treatment of snakebite envenomation, potentially saving thousands of lives annually in affected regions worldwide.

The application of artificial intelligence (AI) to protein design is revolutionizing the development of therapeutics for neglected tropical diseases, with snakebite envenoming being a prime example. This case study examines a breakthrough in the field: the use of the AI platform RFdiffusion to design de novo mini-binders that neutralize lethal three-finger toxin (3FTx) neurotoxins from elapid snakes [4] [18]. This approach represents a paradigm shift from century-old, animal-based antivenom production methods toward a precise, computational design process [41] [42].

The research, published in Nature, demonstrates that these computationally designed proteins exhibit exceptional binding affinity and thermal stability, and provide complete protection in mouse models of envenomation [4] [43]. The following analysis compares the performance of these AI-designed mini-binders against traditional and other emerging alternatives, situating the findings within the broader thesis of validating protein structure prediction tools for challenging targets like snake venom toxins.

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

AI-Driven Protein Design and Validation Workflow

The development of the anti-neurotoxin mini-binders followed a structured, multi-stage workflow that integrated computational design with experimental validation.

1. Target Selection and Analysis: The process targeted key toxins from the 3FTx family: a consensus short-chain α-neurotoxin (ScNtx) and a native long-chain α-neurotoxin (α-cobratoxin) [4]. These toxins disrupt nerve signaling by inhibiting nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) [4] [18].