Visualizing Quality: A Practical Guide to RNA-seq Data Assessment and Visualization

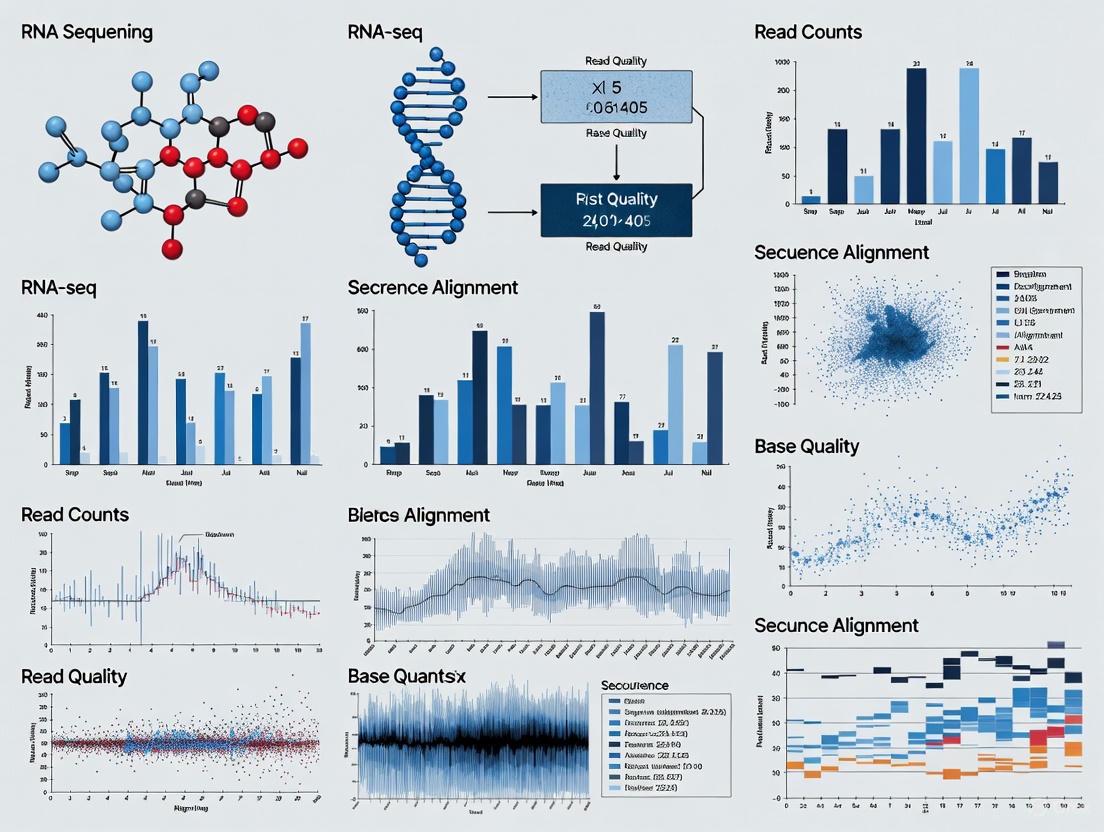

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq data visualization for quality assessment, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development.

Visualizing Quality: A Practical Guide to RNA-seq Data Assessment and Visualization

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to RNA-seq data visualization for quality assessment, tailored for researchers and professionals in drug development. It covers the foundational principles of why visualization is critical for detecting technical artifacts and ensuring data integrity. The guide details practical methodologies and essential tools for creating standard diagnostic plots for both bulk and single-cell RNA-seq data. It further addresses common challenges and pitfalls, offering optimization strategies for troubleshooting problematic datasets. Finally, it explores validation techniques and comparative analyses to benchmark data quality against established standards, empowering scientists to generate robust, publication-ready transcriptomic data.

The Why and What: Foundational Principles of RNA-seq QC Visualization

Understanding the 'Garbage In, Garbage Out' Principle in Bioinformatics

In bioinformatics, the principle of "Garbage In, Garbage Out" (GIGO) dictates that the quality of analytical results is fundamentally constrained by the quality of the input data. This paradigm is particularly critical in RNA-seq analysis, where complex workflows for transcriptome profiling can amplify initial data flaws, leading to misleading biological conclusions. This technical guide examines the GIGO principle through the lens of RNA-seq data quality assessment, providing researchers and drug development professionals with structured frameworks, quantitative metrics, and visualization strategies to ensure data integrity from experimental design through final interpretation. By implementing rigorous quality control protocols at every analytical stage, scientists can prevent error propagation that compromises differential expression analysis, novel transcript identification, and clinical translation of genomic findings.

The GIGO principle asserts that even sophisticated computational methods cannot compensate for fundamentally flawed input data [1]. In RNA-seq analysis, this concept is especially pertinent due to the cascading nature of errors - where a single base pair error can propagate through an entire analytical pipeline, affecting gene identification, protein structure prediction, and ultimately, clinical decisions [1]. The exponential growth in dataset complexity and analysis methods in 2025 has made systematic quality assessment more crucial than ever, with recent studies indicating that up to 30% of published research contains errors traceable to data quality issues at the collection or processing stage [1].

In clinical genomics, these errors can directly impact patient diagnoses, while in drug discovery, they can waste millions of research dollars by sending development programs in unproductive directions [1]. The financial implications are substantial; although the cost of generating genomic data has decreased dramatically, the expense of correcting errors after they have propagated through analysis can be enormous, with research labs and pharmaceutical companies potentially wasting millions on targets identified from low-quality data [1].

Consequences of Poor Data Quality in RNA-seq Studies

Impact on Analytical Outcomes

The table below summarizes the quantitative relationship between data quality issues and their potential impacts on RNA-seq analysis outcomes:

| Data Quality Issue | Impact on RNA-seq Analysis | Potential Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Sequencing Depth | Reduced power to detect differentially expressed genes, especially low-abundance transcripts [2] | Failure to identify biologically significant expression changes; inaccurate transcript quantification |

| Poor Read Quality (Low Q-score) | Increased base calling errors; reduced mapping rates [3] | Incorrect variant calls; false positive novel transcript identification |

| Inadequate Replication | Compromised estimation of biological variance [2] | Reduced statistical power; unreliable p-values in differential expression analysis |

| PCR Artifacts/Duplicates | Skewed transcript abundance estimates [2] | Overestimation of highly expressed genes; distorted expression profiles |

| RNA Degradation | 3' bias in transcript coverage [3] | Inaccurate measurement of full-length transcript abundance |

| Batch Effects | Confounding of biological signals with technical variation [1] | False conclusions about differential expression between experimental groups |

| Adapter Contamination | Reduced alignment rates; false alignments [3] | Loss of data; inaccurate mapping statistics |

Real-World Implications

Beyond analytical distortions, poor data quality in RNA-seq studies carries significant real-world consequences. In clinical settings, decisions about patient care increasingly rely on genomic data, and when this data contains errors, misdiagnoses can occur [1]. For example, in cancer genomics, tumor mutation profiles guide treatment selection, and compromised sequencing data quality could lead to patients receiving ineffective treatments or missing opportunities for beneficial ones [1]. The problem is particularly dangerous because bad data doesn't announce itself—it quietly corrupts results while appearing completely valid, leading researchers down false paths despite flawless code and analytical pipelines [1].

Experimental Design: The First Line of Defense Against GIGO

Foundational Design Considerations

Robust experimental design represents the most effective strategy for preventing GIGO in RNA-seq studies. Thoughtful design choices must address several key parameters:

Biological Replicates: The number of biological replicates directly impacts the ability to detect differential expression. While pooled designs can reduce costs, maintaining separate biological replicates is ideal when resources permit, as they enable estimation of biological variance and increase power to detect subtle expression changes [2]. Studies with low biological variance within groups demonstrate high correlation of FDR-adjusted p-values between pooled and replicate designs (Spearman's Rho r=0.9), but genes with high variance may appear differentially expressed in pooled designs, particularly problematic for lowly expressed genes [2].

Sequencing Depth and Read Length: These parameters significantly impact transcript detection and quantification accuracy. Sufficient sequencing depth is necessary to detect low-abundance transcripts, while longer reads improve mapping accuracy, especially for isoform-level analysis [2]. The choice between paired-end and single-end sequencing also affects splice junction detection and mapping confidence, with paired-end sequencing generally providing more accurate alignment across splice junctions [2].

Technical Variation Mitigation: Technical variation in RNA-seq experiments stems from multiple sources, including RNA quality differences, library preparation batch effects, flow cell and lane effects, and adapter bias [2]. Library preparation has been identified as the largest source of technical variation [2]. To minimize these effects, samples should be randomized during preparation, diluted to the same concentration, and indexed for multiplexing across lanes/flow cells to avoid confounding technical and biological effects [2].

RNA-seq Experimental Design Parameters

The table below outlines key experimental design parameters and their implications for data quality:

| Design Parameter | Recommendation | Impact on Data Quality |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Replicates | Minimum 3 per condition; more for subtle effects [2] | Enables accurate estimation of biological variance; increases statistical power |

| Sequencing Depth | 20-30 million reads per sample for standard DE; higher for isoform detection [2] | Affects detection of low-abundance transcripts; reduces sampling noise |

| Read Type | Paired-end recommended for novel transcript detection, splice analysis [2] | Improves mapping accuracy; enables better splice junction identification |

| Read Length | 75-150 bp, depending on application [2] | Longer reads improve mappability, especially for homologous regions |

| Multiplexing Strategy | Distribute samples across lanes; use balanced block designs [2] | Prevents confounding of technical and biological effects |

RNA-seq Quality Control Workflow: Integrated quality control checkpoints throughout the RNA-seq analytical pipeline help prevent the propagation of errors, embodying the fundamental "Garbage In, Garbage Out" principle in bioinformatics. Each major analytical stage requires specific quality assessment metrics to ensure data integrity [3].

Quality Control Framework for RNA-seq Data Analysis

Primary Analysis: Raw Data Quality Assessment

Primary analysis encompasses the initial processing of raw sequencing data, including demultiplexing, quality checking, and read trimming. At this stage, several critical metrics must be evaluated:

Sequencing Run Quality: Before beginning analysis, sequencing run performance should be evaluated using instrument-specific parameters. The overall quality score (Q30) is particularly important, representing the percentage of bases with a quality score of 30 or higher, indicating a base-calling accuracy of 99.9% [3]. Illumina specifications typically require 80% of bases to have quality scores ≥ Q30 for optimal performance. Additional metrics include cluster densities and reads passing filter (PF), which removes unreliable clusters during image analysis [3].

Demultiplexing and BCL Conversion: Raw data in binary base call (BCL) format must be converted to FASTQ files for downstream analysis. During this process, multiplexed samples are demultiplexed based on their index sequences [3]. Dual index sequencing offers the best chance to identify and correct index sequence errors, salvaging reads that might otherwise be lost [3]. Tools like bcl2fastq or Lexogen's iDemux can perform this demultiplexing with error correction.

Adapter and Quality Trimming: NGS reads often contain adapter contamination, poly(A) tails, poly(G) sequences (from 2-channel chemistry), and poor-quality sequences that must be removed before alignment [3]. Failure to trim these sequences can significantly reduce alignment rates or cause false alignments [3]. Tools like cutadapt and Trimmomatic are widely used for this purpose [3]. For protocols incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), these must be extracted from reads and added to the FASTQ header to prevent alignment issues while preserving the ability to identify PCR duplicates [3].

Secondary and Tertiary Analysis Quality Metrics

Quality control continues through secondary (alignment and quantification) and tertiary (biological interpretation) analysis stages:

Alignment Metrics: During read alignment, key quality metrics include alignment rates, mapping quality scores, and coverage depth [1]. Low alignment rates may indicate sample contamination, poor sequencing quality, or inappropriate reference genome selection. Tools like SAMtools and Qualimap provide these metrics and visualize coverage patterns across the genome [1].

Expression Analysis QC: For transcriptomic data, quality control extends to expression level normalization and outlier detection. Methods like principal component analysis (PCA) can identify samples that deviate from expected patterns, potentially indicating technical issues rather than biological differences [1]. RNA degradation metrics help assess sample quality before sequencing and interpret results appropriately after analysis [1].

Batch Effect Correction: Batch effects occur when non-biological factors introduce systematic differences between groups of samples processed at different times or using different methods [1]. Detecting and correcting batch effects requires careful experimental design and statistical methods specifically developed for this purpose [1].

Essential Quality Control Metrics Table

The table below summarizes critical quality control metrics across RNA-seq analytical stages:

| Analysis Stage | QC Metric | Target Value | Tool Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analysis | Q30 Score | >80% of bases [3] | FastQC, Illumina SAV |

| Read Passing Filter | >90% [3] | Illumina SAV | |

| Adapter Content | <5% | FastQC, cutadapt | |

| Secondary Analysis | Alignment Rate | >70% (varies by genome) [1] | HISAT2, STAR, Qualimap |

| Duplication Rate | Variable; depends on library complexity | Picard, SAMtools | |

| Coverage Uniformity | Even 5'-3' coverage [1] | RSeQC, Qualimap | |

| Tertiary Analysis | Sample Clustering | Groups by biological condition | DESeq2, edgeR, PCA |

| Batch Effect | Minimal separation by technical factors | ComBat, SVA, RUV |

Visualization Strategies for RNA-seq Quality Assessment

Colorblind-Friendly Visualization Principles

Effective visualization of quality metrics is essential for accurate assessment, requiring careful consideration of color choices to ensure accessibility for all researchers. Key principles include:

Color Palette Selection: Standard "stoplight" palettes using red-green combinations are problematic for color vision deficiency (CVD), which affects approximately 8% of men and 0.5% of women [4]. Instead, use colorblind-friendly palettes such as blue-orange combinations or Tableau's built-in colorblind-friendly palette designed by Maureen Stone [4]. For the common types of CVD (protanopia and deuteranopia), blue and red generally remain distinguishable [5].

Leveraging Lightness and Additional Encodings: When color differentiation is challenging, leverage light vs. dark variations, as value differences are perceptible even when hue distinctions are lost [4]. Supplement color with shapes, textures, labels, or annotations to provide multiple redundant encodings of the same information [4] [5]. For line charts, use dashed lines with varying patterns and thicknesses; for bar charts, add textures or direct labeling [5].

Accessibility Validation: Use simulation tools like the NoCoffee Chrome extension or online chromatic vision simulators to verify that visualizations are interpretable under different CVD conditions [4]. When possible, test visualizations with colorblind colleagues to ensure accessibility [4].

Recommended Visualization Approaches by Chart Type

Different visualization types require specific adaptations for effective quality assessment:

Good Choices:

Problematic Choices:

Colorblind-Friendly Visualization Framework: This workflow outlines a comprehensive approach to creating accessible RNA-seq quality assessment visualizations, incorporating color selection guidelines, multiple encoding strategies, and verification methods to ensure interpretability by all researchers, including those with color vision deficiency [4] [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

Implementation of robust RNA-seq quality control requires specific computational tools and methodological approaches. The table below details essential resources for maintaining data integrity throughout the analytical pipeline:

| Tool Category | Specific Tools | Function | Quality Output Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Analysis | bcl2fastq, iDemux [3] | Demultiplexing, BCL to FASTQ conversion | Index hopping rates, demultiplexing efficiency |

| Quality Assessment | FastQC [1], Trimmomatic [3], cutadapt [3] | Read quality control, adapter trimming | Per-base quality scores, adapter content, GC bias |

| Read Alignment | HISAT2 [6], STAR, TopHat2 [2] | Splice-aware alignment to reference genome | Alignment rates, mapping quality distributions |

| Duplicate Handling | Picard [1], UMI-tools [3] | PCR duplicate identification and removal | Duplication rates, library complexity measures |

| Expression Quantification | featureCounts, HTSeq, kallisto | Read counting, transcript abundance estimation | Count distributions, saturation curves |

| Differential Expression | DESeq2 [2], edgeR, limma | Statistical analysis of expression changes | P-value distributions, false discovery rates |

| Quality Visualization | MultiQC, Qualimap [1], IGV [6] | Integrated quality reporting, visual inspection | Summary reports, coverage profiles, browser views |

The "Garbage In, Garbage Out" principle underscores a fundamental truth in bioinformatics: no amount of computational sophistication can extract valid biological insights from fundamentally flawed data. For RNA-seq studies aimed at drug development or clinical translation, implementing systematic quality assessment protocols is not merely optional but essential for producing reliable, reproducible results. By integrating rigorous quality control throughout the entire analytical workflow—from experimental design through primary, secondary, and tertiary analysis—researchers can prevent error propagation that compromises scientific conclusions. The frameworks, metrics, and visualization strategies presented here provide a roadmap for establishing quality-focused practices that mitigate the risks of the GIGO paradigm, ultimately strengthening the validity and translational potential of RNA-seq research.

In the realm of transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has revolutionized our ability to measure gene expression comprehensively. However, the reliability of its results is profoundly dependent on the quality of the underlying data. Technical variations introduced during sample processing, library preparation, sequencing, and data analysis can significantly impact downstream biological interpretations. Within this context, quality assessment through data visualization emerges as a critical first step, enabling researchers to identify technical artifacts and validate data integrity before committing to complex differential expression analyses. This whitepaper focuses on three cornerstone metrics—sequencing depth, GC content, and duplication rates—framing them within a broader thesis that rigorous, upfront quality visualization is a non-negotiable prerequisite for robust RNA-seq research, especially in critical fields like drug development where conclusions can directly influence clinical decisions.

Defining the Core Metrics

Sequencing Depth

Sequencing depth, often referred to as read depth, is a fundamental metric that quantifies the sequencing effort for a sample. In RNA-seq, it is most commonly defined as the total number of reads, often in millions, generated from the sequencer for a given library [7]. While related, the term coverage typically describes the redundancy of sequencing for a given reference and is less frequently used in standard RNA-seq contexts compared to genome sequencing [8] [9]. A crucial distinction must be made between total reads (the raw output from the sequencer) and mapped reads (the subset that successfully aligns to the reference transcriptome or genome). The number of mapped reads is a more accurate reflection of usable data, with a high alignment rate (~90% or above) generally indicating a successful experiment [7].

GC Content

GC content refers to the percentage of nitrogenous bases in a DNA or RNA sequence that are either guanine (G) or cytosine (C). The stability of the DNA double helix is directly influenced by GC content, as GC base pairs form three hydrogen bonds, whereas AT pairs form only two [10]. This biochemical property has direct practical implications for RNA-seq. During library preparation, DNA fragments with high GC content require higher denaturation temperatures in PCR and can lead to challenges in primer annealing and amplification bias, potentially resulting in underrepresented sequences in the final library [10]. Monitoring GC content distribution across reads is therefore essential for identifying such technical biases.

Duplication Rate

The duplication rate measures the proportion of reads that are exact duplicates of one another in a dataset. In RNA-seq, a certain level of duplication is expected and biologically meaningful. Highly expressed transcripts will naturally be sampled more frequently, leading to many reads originating from the same genomic location [11]. However, an exceptionally high duplication rate can also signal technical issues, such as low input RNA leading to a low-complexity library, or biases introduced during PCR amplification. Therefore, visualizing duplication rates helps distinguish between biologically-driven duplication, which is acceptable, and technically-driven duplication, which may compromise data quality [11].

Table 1: Summary of Key RNA-Seq Quality Metrics

| Metric | Definition | Primary Influence on Data Quality | Ideal Range (Typical Bulk RNA-Seq) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Depth | Total number of reads per sample [7]. | Statistical power to detect expression, especially for lowly expressed genes [9]. | 5-50 million mapped reads, depending on goals [9]. |

| GC Content | Percentage of bases in a sequence that are Guanine or Cytosine [10]. | Amplification bias and evenness of coverage across transcripts [10]. | Should match the expected distribution for the organism. |

| Duplication Rate | Percentage of reads that are exact duplicates [11]. | Library complexity; distinguishes highly expressed genes from technical artifacts [11]. | Context-dependent; can be 50-60% in total RNA-seq [11]. |

Quantitative Benchmarks and Experimental Implications

Establishing Optimal Sequencing Depth

The choice of sequencing depth is a balance between statistical power, experimental goals, and cost. For a standard differential gene expression (DGE) analysis in a human transcriptome, 5 million mapped reads is often considered a bare minimum [9]. This depth provides a good snapshot of highly and moderately expressed genes. For a more global view that improves the detection of lower-abundance transcripts and allows for some alternative splicing analysis, 20 to 50 million mapped reads per sample is a common and robust target [9]. It is critical to note that depth alone is not the only factor; the power of a DGE study can often be increased more effectively by allocating resources to a higher number of biological replicates than to excessive sequencing depth per sample [9].

Interpreting GC Content and Duplication Rates

GC content is not a metric with a single "good" value but is instead assessed by its distribution. The calculated GC content for a sample should be consistent with the known baseline for the organism (e.g., humans average ~41% for their genome) and should be uniform across all sequenced samples in an experiment [10]. A skewed GC distribution or systematic differences between samples can indicate PCR bias during library preparation.

Duplication rates in RNA-seq require careful interpretation. Unlike in genome sequencing, where high duplication is a clear indicator of technical problems, in RNA-seq it is an inherent property of the technology due to the vast dynamic range of transcript abundance. As one study notes, a high apparent duplication rate, sometimes reaching 50-60%, is to be expected and is generally not a cause for concern, particularly in total RNA-seq experiments [11]. This is because a few highly expressed genes (like housekeeping genes) can generate a massive number of reads, inflating the duplication rate. The key is to ensure consistency across samples within an experiment.

Table 2: Reagent and Tool Solutions for Quality Control

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in RNA-Seq Workflow |

|---|---|

| Universal Human Reference RNA (UHRR) | A well-characterized reference RNA sample derived from multiple human cell lines, used for benchmarking platform performance and cross-laboratory reproducibility [12]. |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA spikes added to samples in known concentrations. They serve as built-in truth sets for assessing the accuracy of gene expression quantification [13]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Kits | Reagents for constructing RNA-seq libraries that preserve the strand orientation of the original transcript, improving the accuracy of transcript assignment and quantification. |

| rRNA Depletion Kits | Reagents to remove abundant ribosomal RNA (rRNA), thereby increasing the proportion of informative mRNA reads in the library and improving sequencing efficiency. |

| FastQC | A popular open-source tool for initial quality control of raw sequencing reads (FASTQ files), providing reports on per-base quality, GC content, duplication rates, and more. |

Best Practices from Large-Scale Benchmarking Studies

Large-scale consortium-led efforts have systematically evaluated RNA-seq performance across multiple platforms and laboratories, providing critical insights into the sources of technical variation. The Sequencing Quality Control (SEQC) project and the more recent Quartet project represent the most extensive benchmarking studies to date [12] [13].

A key finding from these studies is that reproducibility across different sequencing platforms and laboratories can be problematic. One independent analysis of SEQC data concluded that "reproducibility across platforms and sequencing sites are not acceptable," while reproducibility across sample replicates and FlowCells was acceptable [12]. This underscores the danger of mixing data from different sources without careful quality assessment and normalization.

The Quartet project, which involved 45 laboratories, further highlighted that factors such as mRNA enrichment protocols and library strandedness are primary sources of experimental variation [13]. Furthermore, every step in the bioinformatics pipeline—from the choice of alignment tool to the normalization method—contributes significantly to the final results. These studies collectively affirm that consistent experimental execution, guided by vigilant quality metric visualization, is paramount for generating reliable and comparable RNA-seq data, particularly for clinical applications where detecting subtle differential expression is crucial [13].

Visualization and Analysis Workflows

A robust RNA-seq quality assessment workflow transforms raw data into actionable visualizations that inform researchers on the integrity of their data. The following diagram illustrates the logical progression from raw data to key metric visualization and subsequent decision-making.

Experimental Protocol for Quality Assessment

The following is a generalized protocol for generating and visualizing the key metrics, drawing from standard practices and large-scale study methodologies [13].

- Experimental Design and Spike-Ins: Incorporate technical replicates and, if possible, reference materials like ERCC spike-in controls or standardized RNA (e.g., Quartet or MAQC samples) during library preparation. These provide a "ground truth" for assessing quantification accuracy [13].

- Sequencing and Raw Data Generation: Sequence libraries to a predetermined depth appropriate for the study's goals (see Table 1). The primary output will be FASTQ files containing the raw sequence reads and their quality scores.

- Quality Control Processing: Run the raw FASTQ files through a quality control tool such as FastQC. This tool automatically calculates a suite of metrics, including per-base sequence quality, total reads, GC content distribution, and sequence duplication levels.

- Multi-Sample Aggregation: For studies with multiple samples, use a tool like MultiQC to aggregate the results from individual FastQC reports into a single, integrated report. This is crucial for comparing metrics across all samples in a project.

- Metric Visualization and Interpretation:

- Sequencing Depth: Visualize the total reads (and mapped reads, if available) for each sample using a bar plot. This allows for immediate identification of under-sequenced or over-sequenced outliers.

- GC Content: Plot the GC content distribution as a line graph for each sample, overlaying them for comparison. All samples should show a similar, roughly normal distribution. Deviations indicate potential contamination or bias.

- Duplication Rate: Create a bar plot showing the duplication rate for each sample. Investigate samples with rates significantly higher than the group average, considering the biological context (e.g., high expression of a few genes).

Sequencing depth, GC content, and duplication rates are not merely abstract numbers in a pipeline log file; they are vital signs of an RNA-seq dataset's health. As large-scale benchmarking studies have unequivocally shown, technical variability introduced at both the experimental and computational levels can compromise data reproducibility and the accurate detection of biologically meaningful signals, especially the subtle differential expressions critical in clinical research. Therefore, a systematic approach to visualizing these core metrics is an indispensable component of a rigorous RNA-seq quality assessment framework. By adopting the practices and visualizations outlined in this guide, researchers and drug development professionals can make informed, defensible decisions about their data, ensuring that subsequent biological conclusions are built upon a foundation of reliable technical quality.

This technical guide provides a comprehensive framework for interpreting critical quality assessment plots in RNA-seq data analysis. Within the broader thesis of enhancing reproducibility and accuracy in genomics research, we detail the methodologies for evaluating base quality scores, sequence content, and adapter contamination—three fundamental metrics that directly impact downstream biological interpretations. By integrating quantitative data tables, experimental protocols, and standardized visualization workflows, this whitepaper equips researchers and drug development professionals with systematic approaches for diagnosing data quality issues, thereby supporting the generation of more reliable transcriptomic insights for functional and clinical applications.

Quality assessment through data visualization represents a critical first step in RNA-seq analysis pipelines, serving as a gatekeeper for data integrity and subsequent biological validity. Advances in high-throughput sequencing have democratized access to transcriptomic data across diverse species and conditions, yet the suitability and accuracy of analytical tools can vary significantly [14]. For researchers focusing on microbial, fungal, or other non-model organisms, systematic quality evaluation becomes particularly crucial as standard parameters may not adequately address species-specific characteristics. This guide addresses these challenges by providing a standardized framework for interpreting three cornerstone visualization types, enabling researchers to identify technical artifacts before they compromise differential expression analysis, variant calling, or other downstream applications. The protocols outlined herein are designed to integrate seamlessly into automated workflows, supporting the growing emphasis on reproducibility and transparency in computational biology.

Base Quality Scores: Interpretation and Implications

Fundamental Principles and Mathematical Foundation

Base quality scores, commonly known as Q-scores, provide a probabilistic measure of base-calling accuracy during sequencing. These scores are expressed logarithmically as Phred-quality scores, calculated as Q = -10 × log₁₀(P), where P represents the probability of an incorrect base call [15] [16]. This mathematical relationship translates numeric quality values into meaningful error probabilities, enabling rapid assessment of data reliability across sequencing platforms.

In modern FASTQ files, quality scores undergo ASCII encoding to optimize storage efficiency. The current standard (Illumina 1.8+) utilizes Phred+33 encoding, where the quality score is represented as a character with an ASCII code equal to its value + 33 [15] [16]. For example, a quality score of 20 (indicating a 1% error probability) is encoded as the character '5' (ASCII 53), while a score of 30 (0.1% error probability) appears as '?' (ASCII 63) [15].

Table 1: Quality Score Interpretation Guide

| Phred Quality Score | Error Probability | Base Call Accuracy | Typical ASCII Character (Phred+33) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 1 in 10 | 90% | + |

| 20 | 1 in 100 | 99% | 5 |

| 30 | 1 in 1,000 | 99.9% | ? |

| 40 | 1 in 10,000 | 99.99% | I |

Experimental Protocol for Quality Score Assessment

Tool Selection and Configuration: Multiple software options exist for quality score visualization, each with distinct advantages. FastQC remains the most widely adopted tool for initial assessment, while FASTQE provides a simplified, emoji-based output suitable for rapid evaluation [16]. For integrated workflows, Trim Galore combines quality checking with adapter trimming functionality, and fastp offers rapid processing with built-in quality control reporting [14].

Execution Parameters: When processing RNA-seq data, specify the appropriate encoding format (--encoding Phred+33 for modern Illumina data) to ensure correct interpretation. For paired-end reads, process files simultaneously to maintain synchronization. Set the --nextera flag only when using Nextera-style adapters, as misconfiguration can lead to false positive adapter detection.

Interpretation Protocol: Analyze per-base sequence quality plots systematically:

- Overall Profile: Examine the distribution median, typically represented by a central blue line. Optimal profiles show median scores above Q28 across all bases.

- Score Decay: Note any degradation at the 3' end of reads, which commonly occurs due to enzyme exhaustion in sequencing-by-synthesis technologies. A decline below Q20 warrants consideration of read trimming.

- Interquartile Range: Assess the yellow-shaded interquartile range (25th-75th percentile). Excessive spread indicates inconsistent quality across reads.

- Outlier Detection: Identify whisker extensions representing the 10th and 90th percentiles. Consistently low outliers may suggest technical artifacts or sample-specific issues.

Decision Framework: Based on quality assessment outcomes:

- Q ≥ 30 across all positions: Proceed without quality trimming.

- Q < 20 at read ends: Implement quality-aware trimming.

- Q < 15 across multiple positions: Consider library reconstruction or resequencing.

Sequence Content Analysis: Detecting Composition Biases

Principles of Sequence Composition Assessment

Sequence content plots visualize nucleotide distribution across read positions, revealing technical biases that impact downstream quantification accuracy. In unbiased RNA-seq libraries, the four nucleotides should appear in roughly equal proportions across all read positions, with minor variations expected due to biological factors like transcript-specific composition [14]. Systematic deviations from this expectation indicate technical artifacts that may compromise analytical validity.

Common bias patterns include:

- 5' Bias: Enrichment of specific nucleotides at read beginnings, often resulting from random hexamer priming artifacts in cDNA synthesis.

- 3' Bias: Position-specific composition skewing at read ends, frequently observed in degraded RNA samples or protocols with excessive amplification.

- K-mer Bias: Periodic patterns recurring at specific intervals, typically indicating random hexamer annealing biases during library preparation.

Experimental Protocol for Sequence Content Evaluation

Tool Configuration: FastQC provides integrated sequence content plots with default thresholds. For specialized applications, particularly with non-model organisms, custom k-mer analysis tools such as khmer may provide additional sensitivity for bias detection. When analyzing sequence content in fungal or bacterial transcriptomes, consider adjusting the --organism parameter if available, as GC content variations differ systematically across taxonomic groups.

Execution Workflow:

- Process raw FASTQ files through sequence content analysis modules without prior trimming to capture native composition patterns.

- For paired-end data, analyze forward and reverse reads separately to identify orientation-specific artifacts.

- Generate subset plots for the first 12 bases (hexamer bias detection) and overall distribution.

Interpretation Framework:

- Normal Profile: Minimal separation between nucleotide lines with all four nucleotides maintaining 25% ± 10% at each position.

- Concerning Profile: Systematic separation where one nucleotide deviates beyond 15% from expected distribution for 5+ consecutive positions.

- Critical Profile: Extreme deviations where a single nucleotide exceeds 50% proportion at multiple positions, particularly at read beginnings.

Mitigation Strategies:

- 5' Bias: Employ duplex-specific nuclease normalization or modify priming strategies in library preparation.

- Position-specific Bias: Implement read trimming or use bias-aware alignment tools.

- Global Skew: Verify RNA integrity and consider alternative fragmentation methods.

Table 2: Sequence Content Patterns and Interpretations

| Pattern Type | Visual Characteristics | Common Technical Causes | Recommended Actions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Random Hexamer Bias | Strong nucleotide bias in first 6-12 bases | Non-random primer annealing during cDNA synthesis | Trimmomatic HEADCROP or adapter-aware trimming |

| GC Content Bias | Systematic enrichment of G/C or A/T across positions | PCR amplification artifacts or degradation | Normalize reads or use GC-content aware aligners |

| Sequence-specific Enrichment | Particular motifs at periodic intervals | Contaminating ribosomal RNA or adapter dimers | Enhance RNA enrichment or increase adapter trimming stringency |

| Position-independent Bias | Global deviation across all positions | Species-specific genomic composition | Adjust expected baseline for non-model organisms |

Adapter Contamination: Detection, Quantification, and Remediation

Statistical Framework for Adapter Detection

Adapter contamination occurs when sequences from library preparation adapters are erroneously incorporated into assemblies, systematically reducing accuracy and contiguousness [17] [18]. The standard TruSeq universal adapter sequence ('AGATCGGAAGAG') provides a reference for contamination screening, with statistical significance determined through Poisson distribution modeling.

The expected number of adapter sequences occurring by chance in an assembly of length X with y contigs is given by:

λ = (X - 11y) / 4¹² [17]

The probability of observing k or more adapter sequences by chance is then calculated as:

Pr(O ≥ k) = 1 - e^(-λ) × Σ(λ^j / j!) for j = 0 to k-1 [17]

This statistical framework enables differentiation between stochastic occurrence and significant contamination, with p-value thresholds (< 0.01) indicating biologically meaningful adapter presence after false-discovery rate correction for multiple testing [17].

Experimental Protocol for Adapter Contamination Assessment

Detection Workflow:

- Sequence Screening: Screen all contigs against known adapter sequences (e.g., TruSeq universal adapter: 'AGATCGGAAGAG') including reverse complements.

- Positional Mapping: Record both the presence and precise positional information of adapter matches, noting particularly matches within 300 bases of contig extremities [17].

- Statistical Evaluation: Apply Poisson modeling to determine whether observed adapter frequency exceeds random expectation based on assembly characteristics.

Visualization Approach: Adapter contamination plots typically display:

- Positional Heatmaps: Visualizing adapter density across contig positions, with clustering at termini indicating significant contamination.

- Sequence Logos: Representing adapter fragments and adjacent sequences to identify partial adapter incorporation.

- Comparative Histograms: Showing adapter counts across multiple samples or assemblies for batch quality assessment.

Contamination Remediation Protocol: Based on recent research findings:

- Trimming Implementation: Trim the last (or first) 450 bases of every contig containing adapter sequences within 300 bases of the end (or beginning) [17]. This length optimally balances contamination removal with sequence preservation.

- Reassembly: Following trimming, reassemble trimmed contigs using standard genome assemblers appropriate for the organism.

- Validation: Quantify assembly improvement through N50 metrics, with successful interventions typically increasing N50 by an average of 917 bases, representing up to 20% improvement for individual assemblies [17].

Adapter Contamination Impact on Assembly Quality

Recent comprehensive studies of microbial genome databases have revealed widespread adapter contamination in public resources, with significant consequences for assembly utility. Analysis of 15,657 species reference genome assemblies from MGnify databases identified 1,110 assemblies with significant adapter enrichment (p-value < 0.01), far exceeding the ~157 assemblies expected by chance [17]. This contamination systematically reduces assembly contiguousness by inhibiting contig merging during assembly processes.

The relationship between adapter presence and assembly fragmentation demonstrates a dose-response pattern, with a positive correlation between adapter count and contig merging potential after decontamination (generalized linear model, p-value = 1.99e-5) [17]. This empirical evidence underscores the critical importance of adapter screening even in professionally curated genomic resources, particularly for applications requiring accurate structural variant detection or operon mapping.

Table 3: Adapter Contamination Impact and Remediation Outcomes

| Database | Assemblies with Significant Contamination (p<0.01) | Expected by Chance | Assemblies Improved by Trimming/Reassembly | Average N50 Increase (bases) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human Gut | 295 | ~25 | 87 | 902 |

| Marine | 187 | ~19 | 53 | 811 |

| Mouse Gut | 126 | ~13 | 41 | 976 |

| Cow Rumen | 98 | ~10 | 29 | 894 |

| Honeybee Gut | 74 | ~7 | 22 | 1,025 |

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Quality Assessment

| Tool/Resource | Primary Function | Application Context | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Comprehensive quality control | Initial assessment of raw sequencing data | --encoding, --adapters, --kmers |

| fastp | Integrated quality control and preprocessing | Rapid processing with built-in quality reporting | -q, -u, -l, --adapter_fasta |

| Cutadapt | Adapter trimming and quality filtering | Precise removal of adapter sequences | -a, -g, -q, --minimum-length |

| Trimmomatic | Flexible read trimming | Processing of complex or contaminated datasets | LEADING, TRAILING, SLIDINGWINDOW |

| MultiQC | Aggregate quality reports | Batch analysis of multiple samples | --cl-config, --filename |

| MalAdapter | Specialized adapter detection in assemblies | Quality control of genomic resources | --min-overlap, --p-value-threshold |

Systematic interpretation of base quality scores, sequence content, and adapter contamination plots provides an essential foundation for robust RNA-seq analysis, particularly within the context of growing database contamination concerns. By implementing the standardized protocols and decision frameworks outlined in this guide, researchers can significantly enhance the reliability of their transcriptomic studies, leading to more accurate biological insights. The integration of these quality assessment practices—supported by appropriate statistical testing and visualization tools—will strengthen the validity of downstream applications in both basic research and drug development contexts, ultimately contributing to improved reproducibility in genomic science.

The Critical Role of Biological Replicates in Experimental Design

In the realm of transcriptomics, particularly in RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) experiments, robust experimental design serves as the fundamental pillar upon which biologically meaningful conclusions are built. Among the most critical design elements is the appropriate use of biological replicates—multiple measurements taken from distinct biological units under the same experimental condition. Within the context of RNA-seq data visualization for quality assessment, biological replicates are not merely a luxury but an absolute necessity. They provide the only means to reliably estimate the natural biological variation present within a population, which in turn empowers statistical tests for differential expression and enables the accurate assessment of data quality and reproducibility. Without sufficient replication, even the most sophisticated visualization techniques and analysis pipelines can produce misleading results, confounded by an inability to distinguish true biological signals from random noise. This guide details the pivotal role of biological replicates, providing researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the evidence and methodologies to design statistically powerful and reliable RNA-seq experiments.

Biological vs. Technical Replicates: A Critical Distinction

A foundational step in experimental design is understanding the fundamental difference between biological and technical replicates, as they address fundamentally different sources of variation.

- Biological Replicates are measurements derived from distinct biological samples. Examples include RNA extracted from different animals, individually grown cell cultures, or different patient biopsies. These replicates are essential for measuring the biological variation inherent in the population, which allows researchers to generalize findings beyond the specific samples used in the experiment [19].

- Technical Replicates involve repeated measurements of the same biological sample. For instance, splitting the same RNA extract into multiple libraries for sequencing. Technical replicates are useful for quantifying the technical noise introduced by the experimental protocol, such as library preparation and sequencing [19].

For modern differential expression analysis, biological replicates are considered absolutely essential, while technical replicates are largely unnecessary. This is because technical variation in RNA-seq has become considerably lower than biological variation. Consequently, investing resources in more biological replicates yields a much greater return in statistical power than performing technical replicates on a limited number of biological samples [19]. The following diagram illustrates this conceptual relationship.

The Quantitative Impact of Replicates on Statistical Power

The number of biological replicates in an RNA-seq experiment directly governs its statistical power and the reliability of its findings. A landmark study performing an RNA-seq experiment with 48 biological replicates in each of two conditions in yeast provided concrete data on this relationship [20]. The results demonstrated that with only three biological replicates, commonly used differential gene expression (DGE) tools identified a mere 20%–40% of the significantly differentially expressed (SDE) genes found when using the full set of 42 clean replicates [20]. This starkly highlights the inadequacy of low-replicate designs.

Detection Rates by Replicate Number and Fold Change

The ability to detect differentially expressed genes is influenced not only by the number of replicates but also by the magnitude of the expression change. The following table summarizes how the percentage of true positives identified increases with the number of replicates, stratified by the fold-change of the genes [20].

TABLE 1: Impact of Replicate Number on Detection of Significantly Differentially Expressed (SDE) Genes

| Number of Biological Replicates | Percentage of SDE Genes Identified (All Fold-Changes) | Percentage of SDE Genes Identified (>4-Fold Change) |

|---|---|---|

| 3 | 20% - 40% | >85% |

| 6 | Data not available in source | Data not available in source |

| 12+ | Data not available in source | >85% |

| 20+ | >85% | >85% |

The data reveals a critical insight: while genes with large fold changes (>4-fold) can be detected with high confidence (>85%) even with low replication, comprehensive identification of all SDE genes, including those with subtle but biologically important expression changes, requires substantial replication (20+ replicates) [20]. For most studies where this level of replication is impractical, a minimum of six replicates is suggested, rising to at least 12 when it is important to identify SDE genes for all fold changes [20].

Replicates vs. Sequencing Depth

Another key resource-allocation decision involves balancing the number of biological replicates against sequencing depth (the total number of reads per sample). Empirical evidence demonstrates that increasing the number of biological replicates generally yields more differentially expressed genes than increasing sequencing depth [19]. The figure below illustrates this relationship, showing that the number of detected DE genes rises more steeply with an increase in replicates than with an increase in depth.

Practical Experimental Design and Methodologies

Guidelines for Replicates and Sequencing Depth

Based on empirical data and community standards, the following table provides general guidelines for designing an RNA-seq experiment for different analytical goals [19].

TABLE 2: Experimental Design Guidelines for RNA-seq

| Analytical Goal | Recommended Minimum Biological Replicates | Recommended Sequencing Depth | Additional Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| General Gene-Level Differential Expression | 6 (≥12 for all fold changes) | 15-30 million single-end reads | Replicates are more important than depth. Use stranded protocol. Read length >= 50 bp [20] [19]. |

| Detection of Lowly-Expressed Genes | >3 | 30-60 million reads | Deeper sequencing is beneficial, but replicates remain crucial. |

| Isoform-Level Differential Expression | >3 (Choose replicates over depth) | ≥30 million paired-end reads (≥60 million for novel isoforms) | Longer reads are beneficial for crossing exon junctions. Perform careful RNA quality control (RIN > 7) [19]. |

Protocol: A Step-by-Step Guide for a Robust RNA-seq Experiment

This protocol outlines the key steps for a standard bulk RNA-seq experiment designed for differential gene expression analysis, with an emphasis on incorporating biological replicates and avoiding confounding factors.

Step 1: Define Biological Units and Replicates

- Action: Determine what constitutes an independent biological unit (e.g., a single mouse, a culture of cells derived from a separate passage, a primary tissue sample from a different patient).

- Rationale: This defines the source of your biological replicates. For cell lines, prepare cultures independently using different frozen stocks and freshly prepared media to ensure they are true biological replicates [19].

Step 2: Calculate Sample Size and Randomize

- Action: Based on your budget and the guidelines in Table 2, determine the number of biological replicates per condition (a minimum of 6 is strongly recommended). Randomly assign biological units to control and treatment groups.

- Rationale: Adequate replication is the primary determinant of statistical power. Randomization helps avoid systematic bias.

Step 3: Plan to Avoid Batch Effects

- Action: During the experimental workflow (e.g., RNA isolation, library preparation), do not process all replicates of one group on one day and all replicates of another group on another day. Instead, process samples from all experimental groups in each batch.

- Rationale: This prevents "batch effects" from becoming confounded with your experimental conditions, making it impossible to distinguish technical artifacts from biological effects [19]. The diagram below illustrates a properly designed experiment that avoids confounding.

Step 4: Execute Wet-Lab Procedures and Metadata Recording

- Action: Perform RNA extraction, library preparation, and sequencing. Meticulously record all metadata, including the specific batch (date, researcher, reagent kit lot) for each sample.

- Rationale: High-quality RNA (RIN > 7) is critical. Detailed metadata is essential for including batch as a covariate in the statistical model during analysis to regress out its unwanted variation [19].

Step 5: Primary Data Analysis and Quality Control

- Action: Process raw sequencing data. This includes demultiplexing samples, extracting UMIs (if used), and trimming adapter sequences and low-quality bases using tools like

cutadaptorTrimmomatic[3]. - Rationale: This pre-processing ensures that reads are clean and ready for accurate alignment. Tools like FastQC can be used to verify sequence quality.

Step 6: Secondary Analysis and Visualization-Based QC

- Action: Align cleaned reads to a reference genome (e.g., using STAR or HISAT2) and quantify gene counts (e.g., using featureCounts or HTSeq) [21]. Perform quality assessment using visualizations like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) plots.

- Rationale: PCA plots are a critical visualization tool for quality assessment. They reduce the dimensionality of the gene expression data, allowing you to visualize the overall similarity between samples. With sufficient biological replication, you expect to see samples from the same condition cluster together, with clear separation between conditions. A PCA plot that shows segregation primarily by batch rather than condition is a key indicator of a potential batch effect [21] [19].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

TABLE 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for RNA-seq Experiments

| Item | Function / Rationale |

|---|---|

| RNA Extraction Kit | To isolate high-quality, intact total RNA from biological samples. Essential for ensuring accurate transcript representation. |

| Poly(A) mRNA Magnetic Beads | To enrich for messenger RNA (mRNA) from total RNA by capturing the poly-A tail. Standard for most RNA-seq libraries [21]. |

| cDNA Library Prep Kit | To convert RNA into a sequencing-ready cDNA library. Typically involves fragmentation, reverse transcription, adapter ligation, and PCR amplification [21]. |

| Unique Dual Indexes (UDIs) | To label samples with unique barcode combinations, allowing multiple samples to be pooled ("multiplexed") and sequenced together, then accurately demultiplexed bioinformatically. UDIs minimize index hopping errors [3]. |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Short random nucleotides added to each molecule during library prep. They allow bioinformatic correction for PCR amplification bias, enabling more accurate transcript quantification [3]. |

| Stranded Library Prep Reagents | Reagents that preserve the strand information of the original RNA transcript. This is now considered best practice as it resolves ambiguity from overlapping genes on opposite strands [19]. |

Distinguishing Bulk vs. Single-Cell RNA-seq Quality Assessment Goals

RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has become a cornerstone of modern molecular biology, providing unprecedented insights into gene expression profiles. However, the choice between bulk and single-cell RNA-seq fundamentally shapes experimental design, data output, and quality assessment goals. While bulk RNA-seq measures the average gene expression across a population of cells, single-cell RNA-seq (scRNA-seq) resolves expression at the individual cell level, enabling the dissection of cellular heterogeneity [22] [23]. This technical guide examines the distinct quality assessment goals for these two approaches, providing researchers with a structured framework for evaluating data quality within the broader context of RNA-seq data visualization for quality assessment research.

Fundamental Technological Differences

The core distinction between these technologies lies in their resolution. Bulk RNA-seq processes tissue or cell populations as a homogeneous mixture, yielding a population-averaged expression profile [22] [24]. This approach effectively "masks" cellular heterogeneity, as the true signals from rare cell populations can be obscured by the average gene expression profile [23]. In contrast, scRNA-seq investigates single cell RNA biology, allowing for the analysis of up to 20,000 individual cells simultaneously [23]. This provides an unparalleled view of cellular heterogeneity, revealing rare cell types, transitional states, and continuous transcriptional changes inaccessible to bulk methods [22].

The experimental workflows diverge significantly at the sample preparation stage. Bulk RNA-seq begins with digested biological samples to extract total RNA or enriched mRNA [22]. scRNA-seq, however, requires the generation of viable single-cell suspensions through enzymatic or mechanical dissociation, followed by rigorous counting and quality control to ensure sample integrity [22]. A pivotal technical distinction emerges in cell partitioning: in platforms like the 10X Genomics Chromium system, single cells are isolated into gel beads-in-emulsion (GEMs) where cell-specific barcodes are added to all transcripts from each cell, enabling multiplexed sequencing while maintaining cell-of-origin information [22] [23].

Quality Assessment Goals and Metrics

Quality assessment for RNA-seq data serves two primary domains: experiment design with process optimization, and quality control prior to computational analysis [25]. The metrics used for each approach reflect their fundamental technological differences and specific vulnerability to distinct technical artifacts.

Bulk RNA-seq Quality Metrics

For bulk RNA-seq, quality assessment focuses on sequencing performance, library quality, and the presence of technical biases that might compromise population-level inferences. Key metrics include yield, alignment and duplication rates, GC bias, rRNA content, regions of alignment (exon, intron and intragenic), continuity of coverage, 3′/5′ bias, and count of detectable transcripts [25]. The expression profile efficiency, calculated as the ratio of exon-mapped reads to total reads sequenced, is particularly informative for assessing library quality [25].

Tools like RNA-SeQC provide comprehensive quality control measures critical for experiment design and downstream analysis [25]. Additionally, Picard Tools offers specialized functions for bulk RNA-seq, including the calculation of duplication rates with MarkDuplicates and the distribution of reads across genomic features with CollectRnaSeqMetrics [26]. These metrics help investigators make informed decisions about sample inclusion in downstream analysis and identify potential issues with library construction protocols or input materials [25].

Single-Cell RNA-seq Quality Metrics

scRNA-seq quality assessment addresses distinct technical challenges arising from working with minute RNA quantities from individual cells. Key metrics include cell viability, library complexity, sequencing depth, doublet rates, amplification bias, and unique molecular identifier (UMI) counts [27]. The number of genes detected per cell, total counts per cell, and mitochondrial RNA percentage are crucial indicators of cell quality [27].

Technical artifacts specific to scRNA-seq include "dropout events" (false negatives where transcripts fail to be captured or amplified), "cell doublets" (multiple cells captured in a single droplet), and batch effects (technical variation between sequencing runs) [27]. These require specialized quality control measures not relevant to bulk RNA-seq. For example, cell hashing and computational methods are used to identify and exclude cell doublets from downstream analysis [27].

Table 1: Key Quality Assessment Goals by RNA-seq Approach

| Assessment Category | Bulk RNA-seq Goals | Single-Cell RNA-seq Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Sample Quality | RNA Integrity Number (RIN), rRNA ratio | Cell viability, doublet rate, mitochondrial percentage |

| Sequencing Performance | Total reads, alignment rate, duplication rate | Sequencing depth, saturation, library complexity |

| Technical Biases | GC bias, 3'/5' bias, strand specificity | Amplification bias, batch effects, dropout events |

| Expression Metrics | Detectable transcripts, expression profile efficiency | Genes per cell, UMI counts per cell, empty droplet rate |

| Analysis Preparation | Replicate correlation, count distribution | Cell filtering, normalization, heterogeneity assessment |

Experimental Protocols for Quality Assessment

Bulk RNA-seq Quality Control Protocol

A standardized bulk RNA-seq QC protocol utilizes multiple tools to assess different aspects of data quality:

Initial Quality Assessment: Begin with FastQC or MultiQC to evaluate raw read quality, adapter contamination, and base composition [28]. Review QC reports to identify technical sequences and unusual base distributions.

Read Trimming: Use tools like Trimmomatic or Cutadapt to remove adapter sequences and low-quality bases [28]. Critical parameters include quality thresholds, minimum read length, and adapter sequences.

Alignment and Post-Alignment QC: Map reads to a reference transcriptome using STAR, HISAT2, or pseudoalignment with Salmon [28]. Follow with post-alignment QC using SAMtools or Qualimap to remove poorly aligned or multimapping reads [28].

Detailed Metric Collection:

- Run Picard's

MarkDuplicatesto assess duplication rates [26] - Execute

CollectRnaSeqMetricswith appropriate RefFlat files and strand specificity parameters to evaluate read distribution across genomic features [26] - Use RNA-SeQC for comprehensive metrics including rRNA content, alignment statistics, and coverage uniformity [25]

- Run Picard's

Report Generation: Collate results using MultiQC for integrated visualization of all QC metrics across samples [26].

Single-Cell RNA-seq Quality Control Protocol

scRNA-seq QC requires additional steps to address single-cell specific issues:

Cell Viability Assessment: Before library preparation, evaluate cell suspension quality using trypan blue exclusion or fluorescent viability stains to ensure high viability (>80-90%) [22].

Library Preparation with UMIs: Implement protocols incorporating Unique Molecular Identifiers to correct for amplification bias [27]. The 10X Genomics platform utilizes gel beads conjugated with oligo sequences containing cell barcodes and UMIs [23].

Doublet Detection: Employ computational methods like cell hashing or density-based clustering to identify and remove multiplets [27].

Post-Sequencing QC:

- Calculate metrics for genes per cell, UMIs per cell, and mitochondrial percentage

- Filter out low-quality cells based on thresholds specific to biological system

- Identify and regress out technical sources of variation using tools like Harmony or Scanorama [27]

Dropout Imputation: Apply statistical models and machine learning algorithms to impute missing gene expression data for lowly expressed genes [27].

Table 2: Experimental Solutions for Common RNA-seq Quality Issues

| Quality Issue | Bulk RNA-seq Solutions | Single-Cell RNA-seq Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Input Quality | RNA integrity assessment, ribosomal RNA depletion | Cell viability staining, optimized dissociation protocols |

| Amplification Bias | Sufficient sequencing depth, technical replicates | Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs), spike-in controls |

| Technical Variation | Batch correction algorithms, randomized sequencing | Computational integration (Combat, Harmony), multiplexing |

| Mapping Ambiguity | Transcriptome alignment, multi-mapping read filters | Cell-specific barcoding, unique molecular identifiers |

| Detection Sensitivity | Sufficient sequencing depth (20-30 million reads) | Targeted approaches (SMART-seq), increased cell numbers |

Quality Visualization and Interpretation

Bulk RNA-seq Quality Visualization

For bulk RNA-seq, MultiQC provides consolidated visualization of key metrics across multiple samples [26]. Essential visualizations include:

- Sequence quality plots: Per-base sequencing quality across all reads

- Alignment distribution: Pie charts or bar plots showing exonic, intronic, and intergenic alignments

- Duplication rates: Bar plots comparing duplication levels across samples

- GC bias: Plots showing deviation from expected GC distribution

- 3'/5' bias: Coverage uniformity across transcript length

These visualizations help identify outliers, batch effects, and technical artifacts that might compromise differential expression analysis.

Single-Cell RNA-seq Quality Visualization

scRNA-seq requires specialized visualizations to assess cell quality and technical artifacts:

- Violin plots: Displaying genes per cell, UMIs per cell, and mitochondrial percentage distributions

- Scatter plots: Comparing gene counts versus UMIs to identify low-quality cells

- Dimensionality reduction plots (t-SNE, UMAP): Visualizing cell clusters and potential batch effects

- Doublet visualization: Projecting predicted doublets onto clustering for evaluation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for RNA-seq Quality Assessment

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Viability Stains (Trypan blue, propidium iodide) | Distinguish live/dead cells for viability assessment | scRNA-seq: Pre-library preparation quality control |

| Unique Molecular Identifiers (UMIs) | Molecular barcodes to label individual mRNA molecules | scRNA-seq: Correction for amplification bias |

| ERCC Spike-In Controls | Synthetic RNA molecules of known concentration | Both: Assessing technical sensitivity and quantification accuracy |

| Ribosomal RNA Depletion Kits | Remove abundant rRNA to increase informational sequencing | Both: Especially important for whole transcriptome approaches |

| Single-Cell Barcoding Beads | Gel beads with cell-specific barcodes for partitioning | scRNA-seq: Platform-specific (10X Genomics) cell multiplexing |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert RNA to sequencing-ready libraries | Both: Platform-specific protocols with optimized chemistry |

| Cell Lysis Buffers | Release RNA while maintaining integrity | Both: Composition critical for RNA quality and yield |

| DNase Treatment Kits | Remove genomic DNA contamination | Both: Prevent non-RNA sequencing reads |

| Magnetic Bead Cleanup Kits | Size selection and purification of nucleic acids | Both: Library cleanup and adapter dimer removal |

| Quality Control Instruments (Bioanalyzer, Fragment Analyzer) | Assess RNA integrity and library size distribution | Both: Critical QC checkpoint before sequencing |

Bulk and single-cell RNA-seq demand fundamentally different quality assessment goals rooted in their distinct technological frameworks. Bulk RNA-seq quality control focuses on sequencing performance, library quality, and technical biases affecting population-level averages. In contrast, scRNA-seq quality assessment prioritizes cell integrity, amplification artifacts, and technical variation affecting cellular heterogeneity resolution. Understanding these distinctions enables researchers to select appropriate quality metrics, implement targeted troubleshooting protocols, and accurately interpret data visualizations. As RNA-seq technologies continue evolving with spatial transcriptomics and multi-omic integrations, quality assessment frameworks will similarly advance, maintaining the critical role of rigorous QC in generating biologically meaningful transcriptomic insights.

The How: A Tool-Based Guide to Generating Essential QC Visualizations

In the realm of modern transcriptomics, RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) has emerged as a revolutionary tool for comprehensive gene expression analysis, largely replacing microarray technology due to its superior resolution and higher reproducibility [29]. However, the reliability of biological conclusions drawn from RNA-seq data is intrinsically dependent on the quality of the underlying data [30]. Quality control (QC) visualization represents a fundamental strategic process that forms the foundation of all subsequent biological interpretations, without which researchers risk deriving misleading results, incorrect biological interpretations, and wasted resources [30]. The complex, multi-layered nature of RNA-seq data—spanning sample preparation, library construction, sequencing machine performance, and bioinformatics processing—creates multiple potential points for errors and biases to occur [30].

Within clinical and drug development contexts, where RNA-seq is increasingly applied for biomarker discovery, patient stratification, and understanding disease mechanisms, rigorous quality assessment becomes paramount [31]. A recent systematic review of RNA-seq data visualization techniques and tools highlighted their growing importance for framing clinical inferences from transcriptomic data, noting that effective visualization approaches are essential for helping clinicians and biomedical researchers better understand the complex patterns of gene expression associated with health and disease [31]. This technical guide examines three cornerstone tools—FastQC, MultiQC, and Qualimap—that together provide researchers with a comprehensive framework for assessing RNA-seq data quality throughout the analytical workflow, enabling the detection of technical artifacts and biases that might otherwise compromise biological interpretations [30] [32].

The trio of FastQC, MultiQC, and Qualimap provides complementary functionalities that cover the essential stages of RNA-seq quality assessment. Each tool serves a distinct purpose in the QC ecosystem, from initial raw data evaluation to integrated reporting and RNA-specific metrics.

Table 1: Core Capabilities of Essential QC Visualization Tools

| Tool | Primary Function | Input | Output | Key Strength |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| FastQC | Quality control for raw sequence data | FASTQ files | HTML report with QC plots | Comprehensive initial assessment of read quality |

| MultiQC | Aggregate and summarize results from multiple tools | Output files from various bioinformatics tools | Single integrated HTML report | Cross-sample comparison and trend identification |

| Qualimap | RNA-seq specific quality control | Aligned BAM files | HTML report with specialized metrics | Sequence bias detection and expression-specific assessments |

FastQC functions as the first line of defense in RNA-seq quality assessment, providing a preliminary evaluation of raw sequencing data before any processing occurs [33] [34]. It examines fundamental sequence parameters including base quality scores, GC content, adapter contamination, and overrepresented sequences, generating a detailed HTML report that highlights potential quality issues requiring attention [33] [34]. MultiQC addresses the significant challenge of consolidating and interpreting QC metrics across multiple samples and analysis tools [35]. It recursively searches through specified directories for log files from supported bioinformatics tools (36 different tools at the time of writing), parsing relevant information and generating a single stand-alone HTML report that enables researchers to quickly identify global trends and biases across entire experiments [36] [35]. Qualimap provides RNA-seq specific quality control that becomes relevant after read alignment, generating specialized metrics such as 5'-3' bias, genomic feature coverage, and RNA-seq mapping statistics that are crucial for validating the biological reliability of expression data [32].

The integrated relationship between these tools creates a comprehensive QC pipeline that progresses from basic sequence quality assessment (FastQC) through alignment-based quality metrics (Qualimap), with MultiQC serving as the unifying framework that synthesizes results across all stages [32] [37]. This workflow ensures that quality assessment occurs at each critical juncture of RNA-seq analysis, providing multiple opportunities to detect issues before they propagate through downstream analyses.

Figure 1: Integrated QC Workflow for RNA-Seq Analysis

FastQC: Initial Quality Assessment of Raw Sequencing Data

FastQC serves as the fundamental starting point for RNA-seq quality assessment, providing comprehensive evaluation of raw sequencing data before any processing or alignment occurs [34]. The tool generates a series of diagnostic plots and metrics that help researchers identify potential issues originating from the sequencing process itself, library preparation artifacts, or sample quality problems [33].

Key Metrics and Interpretation Guidelines

FastQC examines multiple dimensions of sequence quality, with several critical metrics requiring special attention in RNA-seq contexts. The per base sequence quality assessment reveals whether base call quality remains high throughout reads or deteriorates toward the ends—a common phenomenon in longer sequencing runs [33] [34]. For RNA-seq applications, a Phred quality score above Q30 (indicating an error rate of 1 in 1000) is generally expected, with significant drops potentially necessitating read trimming [30]. The per sequence quality scores help identify whether a subset of reads has universally poor quality, which might indicate specific technical issues affecting only part of the sequencing run [33].

The per base sequence content plot is particularly important for RNA-seq data, as it can reveal library preparation biases [33] [34]. While random hexamer priming—commonly used in RNA-seq library preparation—typically produces some sequence bias at the 5' end of reads, severe imbalances or unusual patterns throughout reads might indicate contamination or other issues [33]. The adapter content metric is crucial for determining whether adapter sequences have been incompletely removed during demultiplexing, which can interfere with alignment and downstream analysis [33]. The per sequence GC content should approximate a normal distribution centered around the expected GC content of the transcriptome; bimodal distributions or strong shifts may indicate contamination or other library preparation artifacts [33].

Table 2: Critical FastQC Metrics and Their Interpretation in RNA-Seq Context

| Metric | Ideal Result | Potential Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| Per Base Sequence Quality | High quality scores across all bases | Quality drops at read ends | Consider trimming lower quality regions |

| Per Sequence Quality Scores | Sharp peak in high-quality range | Bimodal distribution | Investigate run-specific issues |

| Per Base Sequence Content | Balanced nucleotides with minimal 5' bias | Strong bias throughout read | Check for contamination or library issues |

| Adapter Content | Minimal to no adapter sequences | Increasing adapter toward read ends | Implement adapter trimming |

| Per Sequence GC Content | Normal distribution | Unusual peaks or shifts | Assess potential contamination |

| Sequence Duplication Levels | Low duplication for complex transcriptomes | High duplication rates | May indicate low input or PCR bias |

Experimental Implementation

Implementing FastQC within an RNA-seq workflow typically occurs immediately after receiving FASTQ files from the sequencing facility. The basic execution requires minimal parameters:

For large-scale studies with multiple samples, batch processing can be implemented through shell scripting or integration within workflow management systems. The tool generates both HTML reports for visual inspection and ZIP files containing raw data that can subsequently be parsed by MultiQC [34]. In practice, FastQC results should be reviewed before proceeding to read trimming and alignment, as quality issues identified at this stage may inform parameter selection for downstream processing steps.

MultiQC: Aggregating and Comparing QC Metrics Across Samples

MultiQC addresses one of the most significant challenges in modern RNA-seq analysis: the efficient consolidation and interpretation of QC metrics across multiple samples, tools, and processing steps [35]. As sequencing projects increasingly involve hundreds of samples, manually inspecting individual reports from each analytical tool becomes impractical and error-prone [35]. MultiQC revolutionizes this process by automatically scanning specified directories for log files from supported bioinformatics tools, parsing relevant metrics, and generating a unified, interactive report that facilitates cross-sample comparison and batch effect detection [36] [35].

Comprehensive Tool Integration and Visualization

MultiQC supports an extensive array of bioinformatics tools relevant to RNA-seq analysis, creating a unified visualization framework across the entire workflow [35] [32]. For initial quality assessment, it incorporates FastQC results, displaying key metrics in consolidated plots that enable immediate identification of outliers [32] [34]. From alignment tools like STAR, it extracts mapping statistics including uniquely mapped reads, multimapping rates, and splice junction detection [32] [37]. For expression quantification tools such as Salmon, it integrates information about mapping rates and estimated fragment length distributions [32]. Most importantly, it seamlessly incorporates RNA-specific QC metrics from specialized tools like Qualimap and RSeQC, providing a comprehensive overview of experiment quality [32].