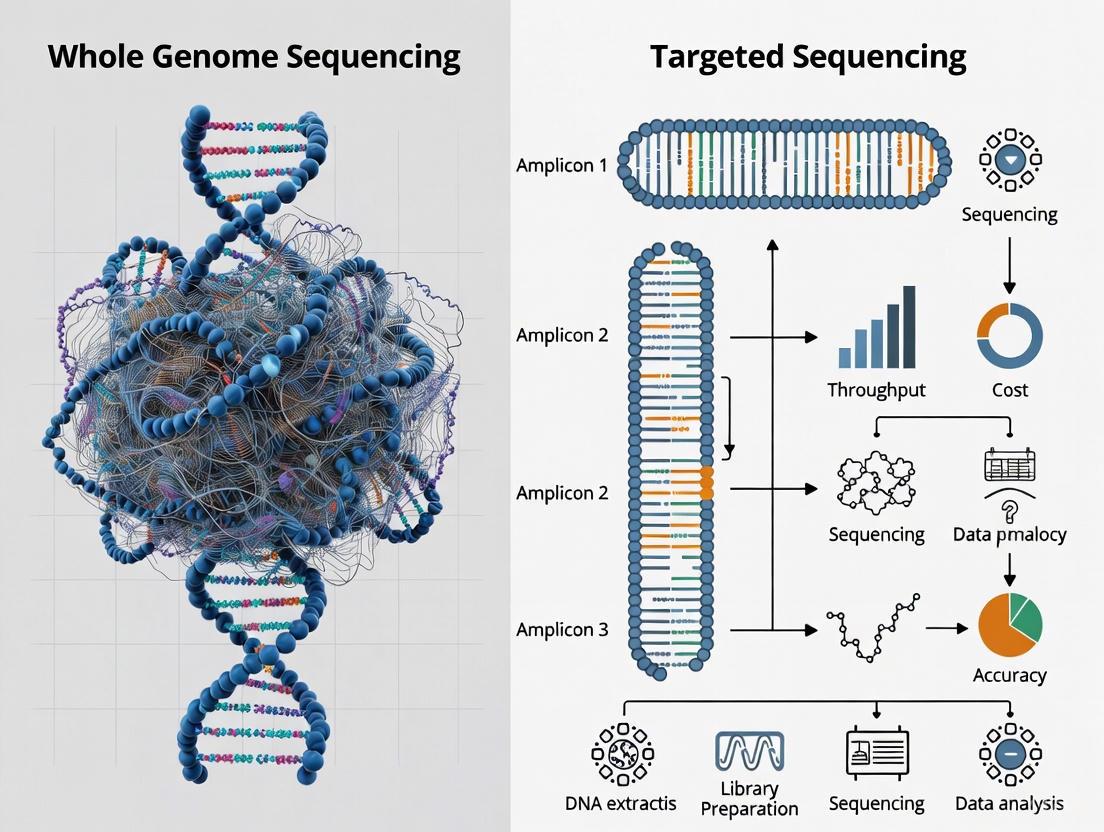

Whole Genome Sequencing vs. Targeted Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Targeted Sequencing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Whole Genome Sequencing vs. Targeted Sequencing: A Strategic Guide for Research and Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Targeted Sequencing for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It covers foundational principles, genomic region coverage, and variant detection capabilities. The content explores methodological workflows, clinical and research applications in oncology, rare diseases, and infectious diseases, and details cost-benefit analyses and strategies for workflow optimization. A direct comparative analysis evaluates performance, data management, and interpretation challenges, offering evidence-based guidance for selecting the appropriate sequencing approach to maximize efficiency and discovery potential in biomedical research.

Core Principles and Genomic Landscapes: Understanding WGS and Targeted Sequencing

In the field of modern genomics, researchers and clinicians are primarily faced with three powerful sequencing approaches: whole-genome sequencing (WGS), whole-exome sequencing (WES), and targeted sequencing panels. Each method offers a distinct balance of breadth, depth, and cost, making them uniquely suited for different research and clinical applications [1] [2]. The fundamental difference lies in the genomic territory they cover—from the entire 3 billion base pairs of the human genome to a focused selection of genes known to be associated with specific diseases [2].

This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform decision-making for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. The choice between these methods is not merely technical but strategic, impacting the depth of analysis, the clarity of results, and the ultimate translational potential of genomic findings in precision medicine.

The following table summarizes the core technical specifications and capabilities of WGS, WES, and targeted panels, providing a foundation for their comparison.

Table 1: Core Technical Specifications of WGS, WES, and Targeted Sequencing

| Feature | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Entire genome (coding & non-coding) [2] | Protein-coding exons (~2% of genome) [2] [3] | Selected genes or regions of interest [3] |

| Approximate Region Size | 3 Gb (3 billion base pairs) [2] | > 30 Mb (30 million base pairs) [2] | Tens to thousands of genes [2] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | > 30X [2] | 50-150X [2] | > 500X [2] |

| Data Output per Sample | > 90 GB [2] | 5-10 GB [2] | Varies with panel size |

| Primary Detectable Variant Types | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions, Structural Variants (SVs) [2] | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions [2] [3] | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions [2] |

| Key Strengths | Comprehensive variant discovery; detection of structural variants and non-coding mutations [3] | Cost-effective focus on known pathogenic variants; good for rare diseases [3] | High depth for sensitive mutation detection; cost-efficient; simplified data analysis [3] |

| Key Limitations | High cost; massive data storage/analysis; interpretation challenges in non-coding regions [3] | Misses non-coding and deep intronic variants; lower sensitivity for structural variants [3] | Limited to known genes; cannot discover novel disease-associated genes [3] |

The hierarchy of genomic coverage is clear: WGS > WES > Targeted Sequencing [2]. WGS provides the most complete picture, while targeted sequencing offers a focused, high-resolution view of pre-defined regions. WES sits in between, capturing a broad swath of the most clinically relevant segments—the exons—where an estimated 85% of known pathogenic variants reside [3].

Experimental Data and Performance Benchmarks

Comparative Analysis in Precision Oncology

A pivotal 2025 study directly compared WES/WGS with transcriptome sequencing (TS) to targeted panel sequencing (TruSight Oncology 500/TruSight Tumor 170) in a clinical setting using samples from 20 patients with rare or advanced tumors [4]. The findings highlight the practical trade-offs between these methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Therapy Recommendations from WES/WGS/TS vs. Panel Sequencing in Oncology

| Metric | WES/WGS with Transcriptome Sequencing (TS) | Targeted Panel Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Median Therapy Recommendations per Patient | 3.5 | 2.5 |

| Basis of Recommendations | 176 biomarkers across 14 categories, including complex biomarkers (TMB, MSI, HRD scores), somatic DNA variants, RNA expression, and germline variants. | Limited to the predefined genes and biomarker types covered by the panel. |

| Overlap | Approximately half of the therapy recommendations were identical between both methods. | |

| Unique Value | Approximately one-third of WES/WGS/TS recommendations relied on biomarkers not covered by the panel. | The majority (8 out of 10) of implemented, molecularly-informed therapies were supported by the panel. |

This study demonstrates that while panel sequencing captures most clinically actionable findings, WES/WGS with TS can provide a significant volume of additional therapeutic options, roughly 30-40% more in this cohort, by uncovering complex biomarkers and alterations outside the panel's scope [4].

Comparative Analysis for Mitochondrial DNA

A 2021 study offers a focused comparison specifically for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) analysis, sequencing 1499 participants from the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) using both WGS and mtDNA-targeted sequencing [5]. The experimental protocol is outlined in the diagram below.

Diagram 1: mtDNA Sequencing Workflow

The study concluded that both methods had a comparable capacity for determining genotypes, calling haplogroups, and identifying homoplasmies (where all mtDNA copies are identical) [5]. However, a key difference emerged in detecting heteroplasmies (a mixture of wild-type and mutant mtDNA within a cell). There was significant variability, especially for low-frequency heteroplasmies, indicating that the sequencing method can influence the detection of these mixed populations [5]. This finding underscores the need for caution when interpreting heteroplasmy data and suggests that targeted sequencing may be sufficient for many mtDNA applications where high-resolution detection of low-level heteroplasmy is not critical.

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The execution of genomic sequencing experiments relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The following table details key materials used in the featured experiments.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing Workflows

| Reagent / Kit / Software | Primary Function | Example Use in Featured Studies |

|---|---|---|

| Kapa Hyper Library Prep Kit | PCR-free library preparation for WGS to reduce amplification bias. | Used in the SARP study for WGS library prep from 500 ng DNA input [5]. |

| REPLI-g Mitochondrial DNA Kit | Whole genome amplification of mtDNA to enrich target regions. | Used for mtDNA-enrichment in the targeted sequencing arm of the SARP study [5]. |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Prep Kit | Rapid library preparation for sequencing from small DNA input. | Used for preparing libraries from mtDNA-enriched samples in the SARP study [5]. |

| BWA (Burrows-Wheeler Aligner) | Aligns sequencing reads to a reference genome. | Used in both the SARP and MASTER studies for aligning reads to the reference genome (rCRS/hg38) [5] [4]. |

| MitoCaller | A likelihood-based method for calling mtDNA variants, accounting for sequencing errors and mtDNA circularity. | The primary variant caller for mtDNA in the SARP study [5]. |

| HaploGrep2 | Tool for determining mtDNA haplogroups from sequencing data. | Used for mtDNA haplogroup classification in the SARP study [5]. |

| Arriba | Software for the rapid discovery of gene fusions from RNA sequencing data. | Used in the reanalysis of the MASTER program data for fusion detection [4]. |

The choice between WGS, WES, and targeted sequencing is not a matter of identifying a single superior technology, but of aligning the tool with the specific research or clinical objective.

For hypothesis-driven research where the genetic targets are well-defined, such as monitoring known cancer drivers, targeted panels offer an efficient, sensitive, and cost-effective solution [3]. For unbiased discovery, the investigation of rare diseases with unknown causes, or the comprehensive assessment of complex biomarkers like TMB and HRD, WGS and WES are indispensable [4] [3]. The continuing decline in sequencing and data storage costs is making WGS increasingly accessible, positioning it as a future first-tier test that can reduce the diagnostic odyssey for many patients [6] [3].

As the field evolves, the integration of artificial intelligence and improved bioinformatics pipelines will be critical for managing and interpreting the vast data generated, particularly by WGS, ultimately unlocking the full potential of precision genomics in research and drug development [7] [3].

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomics, but its effectiveness hinges on two critical metrics: sequencing depth and coverage [8] [9]. While often used interchangeably, they represent distinct concepts. Sequencing depth, or read depth, refers to the average number of times a specific nucleotide is read during sequencing (e.g., 30x) [8] [9]. Coverage describes the percentage of the target genome or region that has been sequenced at least once (e.g., 95%) [8] [9].

The choice between Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) and Targeted Sequencing fundamentally shapes the depth and coverage strategy. WGS aims for comprehensive coverage of the entire genome but typically at a lower, more uniform depth due to cost constraints. Targeted sequencing sacrifices breadth for depth, focusing immense sequencing power on specific regions of interest to detect rare variants with high confidence [1] [10] [8]. This guide objectively compares these approaches, detailing their performance implications through experimental data and standardized methodologies.

Defining the Metrics: A Comparative Framework

The table below summarizes the core differences between Whole Genome and Targeted Sequencing regarding depth, coverage, and their applications.

Table 1: Whole Genome Sequencing vs. Targeted Sequencing - A Comparative Framework

| Aspect | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Targeted Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Scope & Objective | Sequences the entire genome (coding and non-coding regions) to provide an unbiased view and discover novel variants [1] [10]. | Sequences a predefined subset of the genome (e.g., exome, gene panels) to investigate specific, known genetic markers [1] [10]. |

| Typical Depth | 30x - 50x for human genomes [8]. | 50x - 100x for gene mutations; up to 500x-1000x for detecting low-frequency variants in cancer genomics [8]. |

| Coverage Goal | High uniformity across the entire genome, though some complex regions may be challenging to cover [8]. | Very high coverage focused on the targeted regions, ensuring they are comprehensively represented [10] [8]. |

| Primary Applications | Discovery research, novel variant identification, complex disease studies, and de novo genome assembly [10]. | Clinical diagnostics, oncology (e.g., tumor sequencing), and studying inherited disorders with known genetic causes [10] [8]. |

| Cost & Resource Implications | Higher cost due to the extensive sequencing and computational resources required for data analysis [10]. | Generally more cost-effective for focused applications, with simplified data analysis due to reduced data volume [1] [10]. |

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Empirical studies directly comparing sequencing platforms highlight the tangible impact of the depth-coverage trade-off on experimental outcomes.

A key study sequenced a mixture of ten HIV clones using both 454/Roche (longer reads) and Illumina (shorter reads) platforms [11]. For a fixed cost, the experimental data demonstrated that short Illumina reads could be generated at much higher coverage, enabling the detection of variants at lower frequencies [11]. However, the assembly of full-length viral haplotypes was only feasible with the longer 454/Roche reads, underscoring the trade-off between high-depth, short-range variant detection and long-range haplotype reconstruction [11].

The quantitative results from such comparative studies can be summarized as follows:

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison Based on Platform and Strategy

| Sequencing Strategy | Effective Read Length | Effective Depth/Coverage | Variant Detection Sensitivity | Haplotype Reconstruction Capability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina (Short-Read) | Shorter reads (e.g., paired-end 36bp in the cited study) [11]. | Higher coverage for a fixed cost, better for detecting low-frequency single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) [11]. | High sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants within read length [11]. | Limited to local haplotypes; full-length assembly is generally not feasible [11]. |

| 454/Roche (Long-Read) | Longer reads [11]. | Lower coverage for a fixed cost, but reads connect distant variants [11]. | Lower power for detecting very low-frequency variants due to lower coverage [11]. | High power for assembling global haplotypes and resolving the structure of the virus population [11]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear framework for the data discussed, below are detailed methodologies for two common types of experiments cited in comparisons.

Protocol 1: Targeted Sequencing for Variant Detection in Heterogeneous Samples (e.g., Viral Quasispecies or Tumor Biopsies)

This protocol is designed to maximize depth for sensitive variant calling [11] [8].

- Sample Preparation & DNA Extraction: Extract DNA from the sample (e.g., viral RNA converted to cDNA, or genomic DNA from a tumor biopsy). Assess DNA quality and quantity using spectrophotometry or fluorometry.

- Library Preparation - Targeted Enrichment:

- Fragmentation: Fragment the DNA via sonication or enzymatic digestion to a desired size (e.g., 200-500bp) [11].

- Library Construction: Use a kit (e.g., Illumina Genomic DNA sample preparation kit) to repair ends, add 'A' bases, and ligate platform-specific adapters [11].

- Target Enrichment: Employ hybrid capture or PCR amplification to isolate and enrich for the specific genomic regions of interest. This step is crucial for directing sequencing power.

- Sequencing: Load the enriched library onto a high-throughput sequencer (e.g., Illumina). Sequence to a high depth (e.g., ≥500x for low-frequency variants in cancer) using a paired-end protocol to improve mapping accuracy [11] [8].

- Data Analysis:

- Read Mapping: Align the generated reads to a reference genome using a read mapper like Novoalign or SMALT [11].

- Variant Calling: Use specialized software to identify single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels, statistically distinguishing true biological variants from sequencing errors based on the high depth of information [11] [8].

Protocol 2: Whole Genome Sequencing for Comprehensive Variant Discovery

This protocol prioritizes uniform coverage across the entire genome [10] [8].

- Sample Preparation & DNA Extraction: Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA.

- Library Preparation - Whole Genome:

- Fragmentation: Fragment the DNA randomly into smaller pieces.

- Library Construction: As in Protocol 1, repair ends and ligate adapters without a targeted enrichment step. This creates a library representing the entire genome.

- Sequencing: Sequence the library on an appropriate platform (e.g., Illumina, PacBio) to the desired average depth (e.g., 30x for human WGS). The lack of enrichment leads to a more uniform distribution of reads, albeit at a lower average depth per dollar compared to targeted approaches [8].

- Data Analysis:

- Read Mapping & Assembly: Map all reads to the reference genome. For de novo assembly, use sophisticated bioinformatics tools to reconstruct the genome from the short reads without a reference [10].

- Variant Calling & Annotation: Call variants across the entire genome and annotate their potential functional impact in both coding and non-coding regions [10].

Visualizing the Sequencing Strategy Trade-Offs

The logical relationship between sequencing strategy, its characteristics, and its resulting applications can be visualized in the following workflow.

Diagram: Sequencing Strategy Decision Workflow

The fundamental trade-off between read length and depth of coverage for specific genomic tasks is another critical concept, as demonstrated in the HIV quasispecies study [11].

Diagram: Read Length vs. Depth Trade-Off

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key reagents and materials required for the sequencing workflows described in the experimental protocols.

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Sequencing Workflows

| Item | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| High-Quality DNA Extraction Kit | To isolate intact, pure genomic DNA or cDNA from source material (e.g., blood, tissue, cells). | Fundamental first step for both WGS and Targeted Sequencing [8]. |

| Library Preparation Kit (e.g., Illumina DNA Prep) | Contains enzymes and buffers for DNA end-repair, 'A'-tailing, and adapter ligation to prepare fragments for sequencing. | Core library construction for both WGS and Targeted protocols [11] [8]. |

| Targeted Enrichment Probes/Panels | Biotinylated oligonucleotide probes or primer sets designed to hybridize to and capture specific genomic regions of interest. | Essential for Targeted Sequencing to isolate desired genes/exons before sequencing [10]. |

| Sequence-Specific Adapters & Indexes | Short, known DNA sequences ligated to fragments, allowing for sample multiplexing and binding to the sequencing flow cell. | Required for all NGS protocols on platforms like Illumina [11]. |

| Cluster Generation Reagents | Enzymes and nucleotides used on the sequencer to amplify single DNA molecules into clonal clusters, enabling detection. | Core chemistry for sequencing-by-synthesis platforms like Illumina. |

| Polymerase and Fluorescent Nucleotides | The engine of sequencing; a DNA polymerase incorporates fluorescently-labeled terminator nucleotides during each cycle. | Core chemistry for sequencing-by-synthesis platforms like Illumina. |

The choice between Whole Genome and Targeted Sequencing is a strategic decision governed by the fundamental trade-off between depth and coverage. Whole Genome Sequencing offers an unbiased, comprehensive view of the genome, making it indispensable for discovery research. In contrast, Targeted Sequencing provides a cost-effective, high-depth solution for focused investigations where maximum sensitivity for specific, known variants is required. The experimental data and protocols outlined provide a framework for researchers to make an informed choice, ensuring their sequencing strategy is optimally aligned with their biological questions and clinical objectives.

The choice between whole genome sequencing (WGS) and targeted sequencing (TS) represents a fundamental strategic decision in genetic research and clinical diagnostics. While WGS aims to comprehensively interrogate the entire genome, TS focuses on specific regions of interest with enhanced depth and efficiency [12]. Each approach offers distinct advantages and limitations in detecting various types of genetic variants—including single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), insertions and deletions (indels), copy number variations (CNVs), and structural variations (SVs)—that drive biological processes and disease pathogenesis. This guide provides an objective comparison of the variant detection capabilities of these sequencing methodologies, supported by experimental data and detailed protocols to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting appropriate strategies for their specific applications.

Comparative Analysis of WGS and Targeted Sequencing

Table 1: Fundamental characteristics of WGS versus targeted sequencing approaches

| Feature | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Entire genome | Protein-coding exons (~1% of genome) | Selected genes/regions of interest |

| Region Size | ~3 Gb | ~30 Mb | Tens to thousands of genes |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | >30X | 50-150X | >500X |

| Approximate Data Output | >90 GB | 5-10 GB | Varies by panel size |

| Detectable Variant Types | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, SVs, fusions | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, fusions | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, fusions |

| Primary Advantage | Comprehensive variant discovery without prior region selection | Balance between coverage and cost for coding regions | Maximum depth for sensitive variant detection in known regions |

Source: Adapted from CD Genomics comparison [2]

Table 2: Performance metrics for variant calling in WGS

| Variant Type | Recall Rate | Precision | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SNVs | >99.9% [13] | >99.9% [13] | Reduced accuracy in repetitive regions [14] |

| Indels (deletions) | Similar to long-read data in nonrepetitive regions [14] | Similar to long-read data in nonrepetitive regions [14] | Significant reduction in recall for insertions >10 bp [14] |

| Indels (insertions >10 bp) | Significantly lower than long-read data [14] | Varies by algorithm [14] | Performance decreases with increasing indel size [14] |

| Structural Variations | Significantly lower in repetitive regions [14] | Similar to long-read in nonrepetitive regions [14] | Particularly challenging for small-intermediate SVs in repetitive elements [14] |

| Copy Number Variants | 97% (NovaSeq X with DRAGEN) [15] | High but platform-dependent [15] | Coverage drops in GC-rich regions affect some platforms [15] |

The fundamental difference between these approaches lies in their scope and depth. WGS provides unbiased coverage across the entire genome, enabling discovery of novel variants in both coding and non-coding regions [2]. In contrast, TS focuses on predetermined genomic regions, achieving much higher sequencing depths that enhance sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants [12]. This makes TS particularly valuable for applications like tumor sequencing where detection of rare subclones is critical, or for clinical diagnostics where only specific disease-associated genes are of interest [12].

Experimental Protocols for Variant Detection

Whole Genome Sequencing Protocol

Library Preparation and Sequencing The standard WGS protocol begins with quality control of input DNA, typically requiring 100-1000 ng of high-molecular-weight genomic DNA. Library preparation involves fragmentation of DNA to ~350 bp fragments using ultrasonication (e.g., Covaris ultrasonicator) [16]. Following fragmentation, DNA undergoes end repair, A-tailing, and adapter ligation. Libraries are then amplified using cluster generation on a flow cell and sequenced on platforms such as Illumina NovaSeq X Plus using 150 bp paired-end reads, achieving approximately 30-40× coverage [16] [15].

Variant Calling Pipeline Raw sequencing data undergoes base calling to produce raw reads, followed by quality control checks. Quality-filtered reads are aligned to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using BWA-MEM (parameters: mem -t 4 -k 32 -M) [16]. PCR duplicates are marked and removed using SAMTools rmdup [16].

Variant calling employs multiple specialized algorithms:

- SNPs and small InDels: Called using SAMTools mpileup (parameters: -m 2 -F 0.002 -d 1000) with filtering for read depth ≥4 and mapping quality ≥20 [16]

- CNVs: Detected using CNVnator (parameter: -call 100) based on read-depth divergence from reference [16]

- SVs: Identified using BreakDancer for large-scale insertions, deletions, inversions, and translocations based on discordant read pairs and insert size deviations [16]

Functional annotation of variants is performed using tools like ANNOVAR to categorize consequences (exonic, splicing, regulatory etc.) [16].

Targeted Sequencing Protocol

Hybrid Capture-Based Approach The TruSight Rapid Capture kit protocol exemplifies hybrid capture TS. DNA is "tagmented" (fragmented and end-polished using transposons), followed by adapter and barcode ligation [17]. Three to eight libraries are pooled for hybridization with target-specific oligos at 58°C, with two consecutive hybridization cycles to enhance specificity [17]. After capture, libraries are quantified using Bioanalyzer and Qubit assays, diluted to 4 nmol/L, denatured with NaOH, and sequenced with 5% PhiX spike-in for quality control [17].

Amplicon-Based Approach The Ion AmpliSeq protocol represents amplicon-based TS. DNA is amplified in multiple primer pools covering targeted regions, followed by combining PCR products for barcoding and library preparation [17]. Library concentration is measured using TaqMan quantification, adjusted to 40 pmol/L, and loaded onto chips for sequencing [17].

Quality Control and Validation Targeted sequencing requires specific quality metrics:

- On-target rate: Percentage of sequencing data aligning to target regions [2]

- Coverage uniformity: Evenness of coverage across target sites, measured by Fold-80 (additional sequencing needed for 80% of targets to reach mean depth) [2]

- Duplication rate: Percentage of duplicate reads, with lower rates indicating more efficient library complexity [2]

Diagram Title: WGS and TS Experimental Workflows

Performance Assessment and Benchmarking

Reference Materials and Benchmarking Standards

The Genome in a Bottle (GIAB) Consortium developed reference materials for five human genomes, which provide high-confidence "truth sets" of small variants and homozygous reference calls [17]. These materials enable standardized performance assessment across sequencing platforms and analytical pipelines. The GIAB benchmark includes challenging genomic regions such as segmental duplications, low-mappability regions, and repetitive sequences, allowing comprehensive evaluation of variant calling accuracy [15].

Performance metrics follow GA4GH standardized definitions, with sensitivity calculated as TP/(TP+FN) and precision as TP/(TP+FP) [17]. The NIST v4.2.1 benchmark for the HG002 reference genome represents the current gold standard for assessing SNV, indel, and SV calling accuracy [15].

Platform-Specific Performance Characteristics

Table 3: Platform comparison based on benchmarking against GIAB standards

| Platform | SNV Accuracy | Indel Accuracy | Challenging Region Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina NovaSeq X | 99.94% vs. NIST v4.2.1 [15] | 22× fewer errors than UG 100 [15] | Maintains high accuracy in GC-rich regions and homopolymers [15] |

| Ultima Genomics UG 100 | 6× more errors than NovaSeq X [15] | Higher error rate, especially in homopolymers >10 bp [15] | Masks 4.2% of genome including challenging regions [15] |

| Long-read Technologies | High accuracy with PacBio HiFi [14] | Superior for insertions >10 bp [14] | Excellent performance in repetitive regions [14] |

Comparative studies reveal that short-read technologies demonstrate excellent SNV and small deletion detection in nonrepetitive regions, with performance comparable to long-read sequencing [14]. However, short-read platforms show significantly lower recall for insertions larger than 10 bp and for SVs in repetitive regions [14]. The performance gap between short and long reads is less pronounced in nonrepetitive regions [14].

Notably, different platforms employ distinct benchmarking strategies. While Illumina typically assesses performance against the complete NIST benchmark including all challenging regions, other platforms may limit evaluation to "high-confidence regions" that exclude problematic genomic areas, potentially inflating apparent accuracy [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 4: Key reagents and materials for sequencing experiments

| Item | Function | Example Products |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolation of high-quality genomic DNA | Standard phenol-chloroform, column-based kits |

| Library Prep Kits | Fragmentation, end repair, adapter ligation | TruSight Rapid Capture, Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit |

| Target Enrichment | Capture of specific genomic regions | Inherited Disease Panel Oligos, custom baits |

| Sequencing Kits | Cluster generation and sequencing | NovaSeq X Series 10B Reagent Kit, Ion PGM Hi-Q Chef kit |

| Quality Control Tools | Assessment of DNA and library quality | Bioanalyzer, Qubit assays, TapeStation |

| Reference Materials | Method validation and benchmarking | GIAB DNA aliquots, NIST reference materials |

| Alignment Tools | Mapping reads to reference genome | BWA-MEM, Minimap2 |

| Variant Callers | Detection of genetic variants | GATK, DeepVariant, SAMTools, BreakDancer |

Source: Compiled from multiple experimental protocols [16] [17] [15]

The selection between WGS and targeted sequencing involves strategic trade-offs between comprehensiveness and depth, with significant implications for variant detection capabilities. WGS provides the most complete interrogation of the genome, enabling discovery of novel variants across all genomic regions, but at higher cost and data burden [2]. Targeted sequencing offers cost-effective, deep coverage of specific regions of interest, enhancing sensitivity for low-frequency variants but limiting discovery to predetermined targets [12].

The optimal approach depends on research objectives: WGS excels in discovery-phase studies, identification of non-coding variants, and comprehensive structural variant detection, while targeted sequencing proves superior for clinical applications focusing on known disease genes, detection of low-frequency variants in heterogeneous samples, and resource-constrained settings requiring maximal information from specific genomic regions.

As sequencing technologies continue to evolve, with both short-read and long-read platforms demonstrating rapid improvements, regular benchmarking using standardized reference materials remains essential for accurate performance assessment. Researchers should consider their specific variant detection requirements, particularly regarding variant types and genomic contexts, when selecting between these complementary approaches.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- A Timeline of Sequencing Costs

- Comparative Sequencing Methodologies

- Methodology: How Sequencing Costs are Calculated

- The Technology Driving Cost Reduction

- The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Sequencing

- Conclusion & Future Directions

The cost of sequencing a human genome has undergone one of the most dramatic reductions in the history of technology, far outpacing the famed Moore's Law that governed computing progress for decades [18] [19]. This journey from a multi-billion-dollar endeavor to a routine laboratory procedure has fundamentally reshaped biological research and is accelerating the integration of genomics into clinical care. This guide provides an objective comparison of whole-genome sequencing (WGS) against targeted approaches like whole-exome sequencing (WES) and targeted panels, framed within the broader thesis that understanding this cost evolution is critical for selecting the appropriate methodology for research and drug development. The data presented herein consolidates information from leading genomic institutions and recent commercial announcements to offer a clear, data-driven perspective for scientists and researchers.

A Timeline of Sequencing Costs

The following table summarizes the key milestones in the cost of sequencing a human genome, highlighting the accelerated decline with the advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS).

Table 1: Historical and Projected Cost of Sequencing a Human Genome

| Year | Cost (US$) | Notes and Context |

|---|---|---|

| 2001 | ~$100 Million | Cost of the first draft sequence from the Human Genome Project [20]. |

| 2006 | ~$20-$25 Million | Estimated cost using Sanger sequencing technologies prior to NGS [21]. |

| 2008 | ~$1.5 Million | Early NGS begins to significantly outpace Moore's Law [18] [22]. |

| 2015 | ~$4,000 | NHGRI recorded cost for a genome [18] [23]. |

| 2019 | ~$1,000 | NHGRI cost drops below the symbolic $1,000 benchmark [19]. |

| 2022 | ~$500 | NHGRI's final updated benchmark cost [24] [23]. |

| 2023-2024 | ~$100 - $500 | Range of consumable costs claimed for new ultra-high-throughput platforms (e.g., Complete Genomics DNBSEQ-T20x2, Ultima UG100) [19]. |

| 2025 (Projected) | ~$285 | Forecast based on percentage change modeling of NHGRI data [25]. |

It is crucial to distinguish between the often-cited consumable cost (reagents for sequencing) and the total cost of ownership. A 2020 microcosting study in a UK clinical lab found the total cost per rare disease case (a trio) was £7,050, highlighting that consumables were the largest cost component (68-72%), but expenses for equipment, staff, bioinformatics, and data storage are substantial [21]. Furthermore, accessibility and cost vary globally; in Africa, for instance, costs can reach up to $4,500 per genome due to import tariffs and logistical challenges [24].

Comparative Sequencing Methodologies

The choice between WGS, WES, and targeted sequencing involves a fundamental trade-off between the breadth of genomic interrogation, depth of coverage, and cost.

Table 2: Comparison of Whole-Genome, Whole-Exome, and Targeted Sequencing

| Feature | Whole-Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole-Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Sequencing Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Target | ~3 billion bases (100% of nuclear DNA) [20] | ~60 million bases (~2% of the genome that are protein-coding exons) [1] | A select number of specific genes or regions known to harbor disease-relevant mutations [1] |

| Sequenceable Variants | SNVs, indels, CNVs, structural variants, regions outside exons [20] [1] | Primarily SNVs and small indels within protein-coding regions [1] | Pre-defined mutations (e.g., "hot-spots") within the panel's scope [1] |

| Sequencing Depth | Typically 30x-50x | Often >100x due to smaller target | Very high depth (often >500x) |

| Key Advantage | Comprehensive, hypothesis-free; captures non-coding variants [1]. | Cost-effective for focused analysis of protein-coding regions; greater depth for lower cost vs. WGS [1]. | Highest depth for sensitive variant detection; lowest cost per sample; often clinically actionable [1]. |

| Key Limitation | Higher cost per sample; massive data storage/analysis; interpretation challenges in non-coding regions [21]. | Misses variants in introns and other non-coding regulatory regions [1]. | Limited to known genes; cannot discover novel disease-associated genes [1]. |

| Relative Cost (Consumables) | $$$ | $$ | $ |

The decision-making workflow for selecting the appropriate sequencing method based on research goals and constraints can be visualized as follows:

Methodology: How Sequencing Costs are Calculated

Accurately determining the cost of sequencing a genome is complex, as different institutions track and account for costs differently [20]. The National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), a primary source for cost benchmarks, makes a critical distinction between 'production' and 'non-production' activities [18].

NHGRI 'Production' Costs (Included in Benchmarks):

- Labor, administration, utilities, reagents, and consumables

- Sequencing instruments and large equipment (amortized over time)

- Informatics directly related to sequence production (e.g., laboratory information management systems, initial base calling)

- Data submission to public databases

- Indirect costs related to the above items [18]

NHGRI 'Non-Production' Costs (Excluded from Benchmarks):

- Downstream bioinformatic analysis (e.g., sequence assembly, variant calling, interpretation)

- Technology development to improve sequencing pipelines

- Quality assessment/control for specific projects

- Data storage for long-term archiving [18]

This distinction explains why the widely cited "$1,000 genome" for consumables was achieved years before the NHGRI's production cost benchmark fell to the same level [19]. For a research budget, the "complete cost" must include the often-overlooked non-production activities, particularly analysis and storage [21].

The Technology Driving Cost Reduction

The precipitous drop in cost since 2007 is directly attributable to the shift from Sanger sequencing to NGS platforms [18] [19]. Sanger methods read DNA sequences in a single, continuous strand, which was slow and expensive for large genomes. NGS technologies, pioneered by companies like Illumina, broke this paradigm by:

- Massive Parallelization: Sequencing millions to billions of DNA fragments simultaneously.

- Short-Read Sequencing: Breaking the genome into small fragments that are sequenced in parallel and computationally reassembled using a reference genome [20].

The current competitive landscape is driving costs down further. As of late 2024, manufacturers are in a "race to the sub-$100 genome," with platforms like the Complete Genomics DNBSEQ-T20x2 and Ultima Genomics UG100 claiming consumable costs of $100 or less per genome, while Illumina's NovaSeq X Plus targets a $200 genome [19]. This competition not only reduces reagent costs but also improves data output and instrument efficiency.

The Researcher's Toolkit: Essential Components for Sequencing

Beyond the sequencing instrument itself, a functional sequencing pipeline requires a suite of reagents, equipment, and computational resources. The following table details the key components.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials for NGS

| Item | Function | Considerations for Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Extraction Kits | Isolate high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from sample sources (e.g., blood, tissue, cells). | Quality and quantity of input DNA are critical for successful library preparation. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Fragment DNA and attach adapter sequences that allow fragments to bind to the sequencing flow cell. | A key cost and time driver. Kits are often platform-specific. Includes reagents for amplification and purification. |

| Sequenceing-by-Synthesis (SBS) Kits | Core consumables containing enzymes, nucleotides, and buffers for the cyclical sequencing reactions on the instrument. | The primary consumable cost. Format (e.g., flow cell, cartridge) is specific to the sequencing platform. |

| Benchtop Sequencer | The instrument that performs the NGS run (e.g., Illumina iSeq 100, NextSeq 2000; Complete Genomics DNBSEQ-G400). | Choice depends on required throughput, data output, and budget [26] [19]. |

| Nucleic Acid Quantitator | Precisely measure DNA concentration (e.g., fluorometric methods) before library prep and sequencing. | Essential for normalizing samples and ensuring optimal loading on the sequencer. |

| Bioinformatics Software | Process raw data (base calling, alignment), identify variants, and perform functional annotation. | Requires significant computational resources and expertise. Licenses can be a recurring cost. |

| Data Storage Solution | Archive massive sequencing files (FASTQ, BAM, VCF). A single WGS can require over 100 GB of storage [22]. | Costs for on-premise servers or cloud storage must be factored into the project budget. |

The landscape of genome sequencing costs has evolved from the astronomical to the accessible, empowering researchers to design studies at a scale once unimaginable. The choice between WGS and targeted approaches is no longer solely dictated by cost but by the specific scientific question, with WGS offering unparalleled comprehensiveness and targeted methods providing deep, cost-efficient interrogation of known regions.

Looking forward, the race to lower costs continues, with the $100 genome now a reality for consumables on the latest platforms [19]. The next frontier will focus on overcoming the remaining challenges: slashing the total cost of ownership by reducing analysis expenses, improving the efficiency of data storage, and developing automated, standardized interpretation pipelines. Furthermore, achieving global equity in genomic innovation will require addressing the high costs and infrastructure barriers in low- and middle-income countries [24]. For the research and drug development community, this ongoing evolution promises to further democratize access to genomic information, accelerating the pace of discovery and the translation of genomics into personalized medicine.

Workflows and Real-World Applications in Research and Clinical Settings

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, with whole-genome sequencing (WGS) and targeted sequencing representing two fundamental approaches. WGS aims to sequence the entire genome, approximately 3 billion base pairs in humans, providing an unbiased view of all genetic variants [2]. In contrast, targeted sequencing focuses on specific regions of interest, such as protein-coding exons (whole-exome sequencing, WES) or selected gene panels, enabling deeper coverage of predetermined genomic areas at a lower cost [2] [27]. This guide provides a detailed, step-by-step comparison of these methodologies from initial library preparation through bioinformatics analysis, supported by experimental data to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Methodological Comparison: Library Preparation to Sequencing

Library Preparation Workflows

The initial stages of NGS library preparation share common steps regardless of the eventual sequencing strategy, though with important methodological distinctions.

Core Library Preparation Steps (Common to Both Approaches):

- DNA Fragmentation: Genomic DNA is fragmented to appropriate sizes (typically 300-600 bp) using either mechanical shearing (sonication, nebulization, or focused acoustics) or enzymatic digestion [28]. Mechanical shearing offers more consistent fragment sizes with less bias, while enzymatic digestion requires lower DNA input and enables automation [28].

- End Repair and A-Tailing: The fragmented DNA undergoes end repair to create blunt ends, followed by phosphorylation and 3' adenylation to facilitate adapter ligation [28].

- Adapter Ligation: Platform-specific adapters containing sequencing primer binding sites are ligated to both ends of the DNA fragments [28].

- Library Amplification: PCR amplification is performed to enrich for adapter-ligated fragments, though amplification-free protocols exist to minimize bias [28].

Workflow Divergence for Targeted Sequencing:

After initial library preparation, targeted sequencing requires an additional target enrichment step, which can be accomplished through two primary methods:

- Hybridization Capture: Utilizes biotinylated oligonucleotide probes complementary to target regions. Target-probe hybrids are captured using magnetic beads, while non-target sequences are washed away [28] [27]. This method offers more uniform coverage and is preferred for exome sequencing and detecting rare variants [27].

- Amplicon Sequencing: Employs highly multiplexed PCR with primers designed to amplify specific target regions [28]. This approach requires fewer steps and less input DNA, making it suitable for detecting germline inherited variants and CRISPR editing events [27].

Table 1: Key Differences Between WGS and Targeted Sequencing

| Parameter | Whole Genome Sequencing | Whole Exome Sequencing | Targeted Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Entire genome (~3 Gb) | Protein-coding exons (~30 Mb) | Selected genes/regions (varies) |

| Region Size | ~3 billion bp | ~30 million bp | Tens to thousands of genes |

| Sequencing Depth | Typically 30X-50X | Typically 50X-150X | Typically >500X |

| Data Output | >90 GB per sample | 5-10 GB per sample | Varies with panel size |

| Detectable Variants | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion, Structural variants | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion | SNPs, InDels, CNV, Fusion |

| Target Enrichment | Not required | Hybridization capture | Hybridization capture or amplicon sequencing |

Sequencing and Data Generation

Following library preparation, samples are loaded onto sequencing platforms. The choice between WGS and targeted sequencing significantly impacts downstream data characteristics:

Coverage and Depth: WGS provides uniform coverage across the entire genome but at relatively lower depth due to cost constraints. Targeted sequencing achieves much higher depth in specific regions, enhancing sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants [2]. For example, targeted sequencing can detect variants with allele frequencies as low as 1% using hybridization capture without UMIs, and even lower with UMIs [27].

Technical Considerations: The sequencing platform itself introduces technical variability. Studies show that different platforms can yield varying results, with one study reporting only 88.1% concordance for single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) and 26.5% for indels between Illumina and Complete Genomics platforms [29]. Additionally, the amount of input DNA significantly impacts sequencing success, particularly for targeted approaches where insufficient DNA can lead to library preparation failure or adapter contamination [30].

Experimental Data and Performance Comparison

Concordance Studies

Direct comparisons between WGS and targeted sequencing reveal important patterns in variant detection:

Pancreatic Cancer Study: A 2025 paired comparison of WGS and targeted sequencing (Ion Torrent Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus) in pancreatic cancer patients demonstrated 81% concordance across all variants and 100% concordance for variants relevant to targeted therapy [31]. Both techniques reliably identified common driver mutations, suggesting that for clinical applications focused on known therapeutic targets, targeted sequencing performs comparably to WGS [31].

Mitochondrial DNA Analysis: A large-scale comparison of WGS and mtDNA-targeted sequencing in 1,499 participants from the Severe Asthma Research Program revealed that both methods had comparable capacity for determining genotypes, calling haplogroups, and identifying homoplasmies [5]. However, significant variability emerged in calling heteroplasmies, particularly for low-frequency variants, highlighting method-specific limitations in detecting mixed populations [5].

Detection Capabilities

The comprehensive nature of WGS enables discovery of variant types typically missed by targeted approaches:

Structural Variants and Non-coding Regions: WGS can identify structural variants (inversions, duplications, translocations) and variations in non-coding regulatory regions that are not covered by targeted panels [2] [28]. These elements may play crucial roles in disease pathogenesis but remain inaccessible to targeted methods.

Rare Variant Detection: While targeted sequencing achieves higher depth for detecting rare variants in specific regions, WGS provides the advantage of genome-wide rare variant discovery without prior knowledge of target regions [27].

Table 2: Performance Comparison Based on Experimental Data

| Performance Metric | Whole Genome Sequencing | Targeted Sequencing |

|---|---|---|

| Variant Concordance | 81-88% with other WGS platforms | 81-100% with WGS for known variants |

| Rare Variant Detection | Genome-wide, but limited by depth | Enhanced in targeted regions (>500X depth) |

| Structural Variant Detection | Comprehensive | Limited to designed targets |

| Heteroplasmy Detection | Variable for low-frequency variants | Variable for low-frequency variants |

| Input DNA Requirements | 500 ng (PCR-free) | 1-250 ng (hybridization capture); 10-100 ng (amplicon) |

Bioinformatics Pipelines and Computational Considerations

Data Processing Workflows

Bioinformatics pipelines for NGS data share fundamental steps but differ in scale and specific approaches:

Primary Data Processing (Common Steps):

- Quality Control: Assessment of raw sequencing data using tools like FastQC to evaluate base quality scores, GC content, and adapter contamination [2].

- Read Alignment: Mapping sequencing reads to a reference genome using aligners such as BWA-MEM or BWA-aln (for reads <70bp) [32]. The choice of aligner affects reproducibility, with some tools like BWA-MEM showing variability when read order is altered [33].

- Duplicate Marking: Identification and flagging of PCR duplicates using tools like Picard MarkDuplicates to prevent variant calling artifacts [32].

- Local Realignment: Correction of misalignments around indels using GATK's IndelRealigner [32].

- Base Quality Score Recalibration: Adjustment of systematic errors in base quality scores using GATK's BaseRecalibrator [32].

Variant Calling and Annotation:

- WGS-Specific Considerations: The comprehensive nature of WGS data requires specialized approaches for detecting structural variants and copy number variations, often employing multiple algorithms [32].

- Targeted Sequencing Considerations: The higher depth in targeted regions enhances sensitivity for somatic variant detection but requires careful handling of off-target reads [2].

- Variant Annotation: Identified variants are annotated with functional information using tools like ANNOVAR to interpret potential biological impacts [2].

Reproducibility and Technical Variability

Bioinformatics tools significantly impact reproducibility, defined as the ability to maintain consistent results across technical replicates [33]. Key considerations include:

Algorithmic Biases: Alignment algorithms may exhibit reference bias, favoring sequences containing reference alleles [33]. Tools employ different strategies for handling multi-mapped reads in repetitive regions, affecting variant calling consistency [33].

Stochastic Variations: Some algorithms incorporate random processes (e.g., Markov Chain Monte Carlo) that can produce different outcomes even with identical input data [33]. Setting random seeds can restore reproducibility in such cases.

Pipeline Selection: No single bioinformatics pipeline has emerged as universally superior. The GDC DNA-Seq pipeline, for instance, implements four separate variant calling pipelines (MuTect2, MuSE, Pindel, VarScan) to provide comprehensive variant detection [32].

Workflow Visualization

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hyper Library Preparation Kit (PCR-free) | Library preparation without amplification bias | Ideal for WGS with sufficient DNA input [5] |

| REPLI-g Mitochondrial DNA Kit | Whole mitochondrial genome amplification | Enables mtDNA-targeted sequencing [5] |

| Nextera XT DNA Library Preparation | Transposon-based library preparation | Faster workflow; fragments and tags simultaneously [28] |

| xGen Hybridization Capture Probes | Target enrichment via hybridization | High uniformity; suitable for exome sequencing [27] |

| Oncomine Comprehensive Assay Plus | Targeted cancer panel | Designed for therapeutic biomarker detection [31] |

| BWA Aligner | Sequence alignment to reference genome | Industry standard; BWA-MEM for reads ≥70bp [32] |

| GATK Tools | Variant discovery and genotyping | Provides base quality recalibration, variant calling [32] |

| Picard Tools | SAM/BAM file processing | Handles duplicate marking, file sorting/merging [32] |

The choice between WGS and targeted sequencing involves trade-offs between comprehensiveness and depth. WGS provides unbiased genome-wide coverage, enabling discovery of novel variants and structural variations outside coding regions [2] [28]. Targeted sequencing offers cost-effective, deep coverage of predefined regions, enhancing sensitivity for detecting low-frequency variants and streamlining data analysis [27] [31].

For clinical applications focused on known therapeutic targets, targeted sequencing demonstrates high concordance with WGS while being more resource-efficient [31]. For discovery-oriented research or when investigating non-coding regions, WGS remains the superior approach. Future directions may include hybrid strategies that combine targeted sequencing with low-pass WGS to balance cost and comprehensiveness.

Researchers should select the appropriate method based on their specific research questions, available resources, and desired balance between novel discovery and focused interrogation of genomic regions.

Within the context of a broader thesis comparing whole-genome sequencing to targeted sequencing research, target enrichment stands out as a critical methodological step that enables cost-effective and deep investigation of specific genomic regions. While whole-genome sequencing provides a comprehensive view, its cost and data complexity can be prohibitive for many applications [34]. Targeted sequencing, through enrichment techniques, allows researchers to focus sequencing resources on regions of interest, leading to higher coverage depths, simplified data analysis, and significantly reduced costs [35] [36]. The two most prevalent enrichment methods—hybridization capture and amplicon sequencing—offer distinct advantages and limitations that researchers must carefully consider based on their experimental goals, sample types, and resource constraints. This guide provides an objective comparison of these techniques to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals in selecting the appropriate methodology for their specific applications.

Fundamental Principles and Workflows

Amplicon Sequencing (Multiplex PCR-Based)

Amplicon sequencing utilizes polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to directly amplify specific genomic regions of interest. In this method, multiple primer pairs are designed to flank target sequences and work simultaneously in a multiplexed PCR reaction to create thousands of amplicons [37]. These amplified products are then processed into sequencing libraries by adding platform-specific adapters and sample barcodes [35]. The method is particularly valued for its simplicity and efficiency, enabling rapid library preparation from minimal DNA input—as little as 1 ng in some validated systems [34] [37]. This makes it especially suitable for challenging samples such as formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) tissue, fine needle aspirates, or circulating tumor DNA where sample material is limited [34].

Hybridization Capture-Based Enrichment

Hybridization capture employs biotinylated oligonucleotide probes (baits) that are complementary to targeted genomic regions. The process begins with fragmentation of genomic DNA, followed by adapter ligation and library preparation [35] [37]. The library is then denatured and hybridized with the bait probes in solution. Biotin-labeled probe-target hybrids are captured using streptavidin-coated magnetic beads, while non-target fragments are washed away [37]. The enriched targets are then amplified via PCR before sequencing. This method is particularly advantageous for capturing large genomic regions, with virtually unlimited capacity for targets per panel, making it the preferred approach for whole-exome sequencing and large gene panels [35] [38].

Visual Comparison of Core Workflows

The fundamental differences between these techniques are reflected in their experimental workflows, as illustrated below.

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Technical Comparison

Extensive evaluations of both methodologies have revealed distinct performance characteristics that directly impact their application suitability. The table below summarizes key comparative metrics derived from published studies.

Table 1: Comprehensive Performance Comparison Between Hybridization Capture and Amplicon Sequencing

| Performance Metric | Hybridization Capture | Amplicon Sequencing | Experimental Context & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| On-Target Rate | Variable (typically 50-80%); lower for small panels [39] | Consistently high (>90%); superior for small panels [40] [39] | Amplicon methods achieve higher specificity via primer design [38] |

| Coverage Uniformity | Superior (Fold-80 penalty: ~1.5-2) [40] [41] | Lower uniformity (Fold-80 penalty: >2) [40] | Hybridization demonstrates more even base coverage [40] |

| Sensitivity | <1% variant frequency [35] | <5% variant frequency [35] | Hybridization better for low-frequency variants [35] |

| Sample Input Requirement | 50-500 ng (typical) [35] [37] | 1-100 ng; works with degraded samples [35] [34] [37] | Amplicon superior for limited/scarce samples [37] |

| Variant Detection False Positives/Negatives | Lower noise and fewer false positives [38] | Higher potential for false positives/negatives near primer sites [40] | Amplicon methods can miss variants detected by capture [40] |

| GC Bias | Moderate; better for extreme GC regions [40] | Higher PCR-induced bias [40] [41] | Hybridization handles diverse GC content more effectively [40] |

Practical Implementation Comparison

Beyond technical performance, practical considerations significantly influence method selection for specific research environments and applications.

Table 2: Practical Implementation Characteristics and Application Fit

| Characteristic | Hybridization Capture | Amplicon Sequencing | Implications for Research Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| Workflow Steps | More steps (fragmentation, overnight hybridization, captures) [38] [39] | Fewer steps (multiplex PCR, purification) [35] [38] | Amplicon enables faster turnaround (hours vs. days) [39] |

| Target Capacity | Virtually unlimited (entire exomes) [35] [38] | Flexible, usually <10,000 amplicons per panel [35] [38] | Hybridization preferred for large targets (>1 Mb) [39] |

| Cost Per Sample | Higher (reagents, sequencing) [35] [38] | Generally lower [35] [38] | Amplicon more cost-effective for focused panels [39] |

| Hands-On Time | Significant (multiple handling steps) [39] | Minimal (streamlined workflow) [39] | Amplicon more efficient for high-throughput applications |

| Best-Suited Applications | Whole-exome sequencing, large gene panels, rare variant discovery, cancer research [35] [38] | Genotyping by sequencing, CRISPR validation, germline SNPs/indels, disease-associated variants [35] [38] | Application dictates optimal method selection |

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of either target enrichment strategy requires specific reagent systems and tools. The following table outlines essential materials and their functions for both methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Target Enrichment

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Workflow | Method Compatibility |

|---|---|---|---|

| Library Preparation | KAPA HyperPrep, Illumina TruSeq, Ion AmpliSeq | Fragments DNA, adds platform-specific adapters, incorporates sample indices | Both Methods |

| Enrichment Probes/Primers | Agilent SureSelect, IDT xGen, Roche SeqCap, Ion AmpliSeq Primers | Target-specific oligonucleotides for capture or amplification | Method-Specific |

| Capture Materials | Streptavidin-coated magnetic beads | Binds biotinylated probes for target isolation | Hybridization Capture |

| Enzymatic Mixes | Polymerases, ligases, restriction enzymes | Amplifies targets, ligates adapters, digests unused primers | Both Methods (different types) |

| Design Tools | Agilent eArray, Roche HyperDesign, ParagonDesigner | In silico probe/primer design and coverage analysis | Both Methods |

| Quality Control | Agilent Bioanalyzer, Qubit Fluorometer, TapeStation | Assesses DNA quality, quantity, and library fragment size | Both Methods |

Experimental Protocols for Method Evaluation

Standardized Hybridization Capture Protocol

Based on methodologies from comparative studies [42] [40], a representative hybridization capture protocol includes:

DNA Fragmentation: Dilute 1-3 μg genomic DNA and shear to a target peak of 150-300 bp using a focused-ultrasonicator (e.g., Covaris S220) per manufacturer's specifications [40].

Library Preparation: Use a validated library prep kit (e.g., Illumina TruSeq) to repair DNA ends, add platform-specific adapters containing sample barcodes, and perform limited-cycle PCR amplification [40].

Hybridization: Combine the library with biotinylated RNA or DNA probes (e.g., Agilent SureSelect) in hybridization buffer. Incubate at 65°C for 16-24 hours to allow probe-target hybridization [42] [40].

Target Capture: Add streptavidin-coated magnetic beads to bind biotinylated probe-target hybrids. Wash repeatedly with optimized buffers to remove non-specifically bound DNA [37] [40].

Post-Capture Amplification: Elute captured targets from beads and perform 10-14 cycles of PCR to amplify the enriched library for sequencing [40].

Quality Control: Validate library quality using appropriate methods (e.g., Agilent TapeStation) and quantify using fluorometric methods before sequencing [40].

Representative Amplicon Sequencing Protocol

Based on established systems like Ion AmpliSeq [34] [40]:

Panel Design/Primer Pool Preparation: Design primers to flank all targets of interest. For custom panels, use design tools (e.g., Ion AmpliSeq Designer) that leverage algorithms to select optimal primers with minimal interference [34].

Multiplex PCR: Combine 10-250 ng DNA with primer pools (up to 24,000 primer pairs in a single reaction) and robust PCR mix. Amplify with thermal cycling conditions optimized for the specific panel [34] [40].

Primer Digestion: Treat PCR products with enzymes (e.g., FuPa enzyme in Ion AmpliSeq) to partially digest primers and phosphorylate DNA ends in preparation for adapter ligation [34].

Adapter Ligation: Add barcoded adapters to amplicons using ligase enzyme. These adapters contain platform-specific sequences, sample indices, and sequencing primer binding sites [34].

Library Purification: Clean up the final library using magnetic beads to remove enzymes, salts, and unused adapters [34] [39].

Quality Assessment: Evaluate library quality and quantity using appropriate methods (e.g., Agilent High Sensitivity D1K ScreenTapes) before sequencing [40].

Application-Oriented Method Selection Guide

The choice between hybridization capture and amplicon sequencing is primarily driven by research goals, target size, and sample characteristics. The decision pathway below provides a systematic approach to method selection.

Both hybridization capture and amplicon sequencing offer powerful, complementary approaches for target enrichment in next-generation sequencing applications. Hybridization capture excels in applications requiring comprehensive coverage of large genomic regions, superior uniformity, and detection of low-frequency variants. In contrast, amplicon sequencing provides an optimal solution for focused panels, challenging sample types, and high-throughput applications where workflow efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and rapid turnaround are paramount. The choice between these methodologies should be guided by specific research objectives, target characteristics, sample quality, and available resources. As targeted sequencing continues to evolve, both techniques will remain essential tools in the researcher's arsenal, enabling deeper insights into genomic variation and its role in disease and biological processes.

In the evolving landscape of genomic analysis, the choice between whole genome sequencing (WGS) and targeted sequencing is pivotal for research and clinical applications. This guide provides an objective comparison of these technologies, focusing on their performance in gene discovery and variant detection, supported by experimental data and current market trends.

Next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized genomic research, enabling high-throughput, cost-effective analysis of DNA and RNA [43]. The two primary approaches—whole genome sequencing (WGS) and targeted sequencing—differ fundamentally in scope and application. WGS aims to sequence the entire genome, approximately 3 billion base pairs in humans, providing a comprehensive view of all genetic information, including both coding and non-coding regions [1] [2]. In contrast, targeted sequencing focuses on a curated set of genes or regions of interest, such as the exome (whole-exome sequencing, or WES) or smaller gene panels [2]. While WGS captures the complete genetic blueprint, targeted methods provide deeper coverage of specific regions at a lower cost per sample, making each suitable for distinct research scenarios [1] [2].

Technical Comparison and Performance Data

The technical performance of WGS and targeted sequencing varies significantly across key parameters, influencing their suitability for different research objectives.

Table 1: Key Technical Specifications of Sequencing Approaches

| Parameter | Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) | Whole Exome Sequencing (WES) | Targeted Panels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sequencing Region | Entire genome (∼3 billion bases) [2] | Exonic regions only (∼30 million bases) [2] | Selected regions (dozens to thousands of genes) [2] |

| Typical Sequencing Depth | > 30X [2] | 50-150X [2] | > 500X [2] |

| Data Volume per Sample | > 90 GB [2] | 5-10 GB [2] | Varies with panel size [2] |

| Detectable Variant Types | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions, Structural Variants [2] | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions [2] | SNPs, InDels, CNVs, Fusions [2] |

| Ability to Discover Novel Genes/Regions | High (comprehensive, hypothesis-free) [43] | Limited to exons [1] | None (restricted to pre-defined panel) [1] |

Table 2: Performance Comparison in Clinical and Research Settings

| Application | WGS Performance & Advantages | Targeted Sequencing Performance & Advantages |

|---|---|---|

| Novel Gene Discovery | Excellent; uncovers variants in non-coding regions and novel structural variants [43] [2]. | Not applicable, as limited to known targets [1]. |

| Rare Variant Detection | Good, but limited by moderate depth. May miss very low-frequency variants [1]. | Excellent; high depth (>500X) enables detection of very low-frequency variants [1] [2]. |

| Clinical Diagnostics (e.g., NICU) | Rapid WGS can provide a hypothesis-free diagnosis in hours [44] [45]. | Targeted panels are efficient when a specific set of disorders is suspected. |

| Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT) | Lower failure rates, simpler PCR-free workflow, comprehensive view [46]. | Targeted approaches (e.g., SNP, microarray) analyze limited regions, have more complex workflows [46]. |

| Cost-Effectiveness | Higher per-sample cost; cost-effective for hypothesis-free discovery [47]. | Lower per-sample cost; highly cost-effective for focused, high-volume testing [48]. |

Experimental Data and Protocol Analysis

Case Study: Ultra-Rapid WGS in a Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU)

A groundbreaking study published in 2025 demonstrated the power of WGS in a critical care setting. Researchers from Roche, Broad Clinical Labs, and Boston Children's Hospital set a new world record by sequencing and analyzing a whole human genome in under four hours (3 hours, 57 minutes) [44] [45].

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Collection: Blood was drawn from NICU infants at the hospital [44].

- Sample Transport: A courier transported the samples to the sequencing facility [44].

- Sequencing Technology: Used Roche's novel Sequencing by Expansion (SBX) technology. This method converts DNA into an expanded surrogate molecule (Xpandomer), generating a high signal-to-noise ratio and enabling extremely fast sequencing [44].

- Data Analysis & Reporting: Sequencing data was continuously analyzed in near real-time. The fastest instance achieved a blood-to-report turnaround time of just 8 hours (6:30 a.m. to 2:30 p.m.) [44].

Results and Implications: The study sequenced 15 genomes, including seven from the NICU. The rapid results, aligning with findings from parallel tests, showcase the potential of WGS to inform urgent clinical decisions, such as avoiding unnecessary procedures and initiating targeted, life-saving treatments for critically ill babies within a single work shift [44] [45].

Protocol for Comparative Technology Assessment

The FDA-led Sequencing Quality Control Phase 2 (SEQC2) project provides a robust framework for comparing sequencing technologies [43].

- Sample Preparation: The study uses well-characterized reference samples, such as the Agilent Universal Human Reference (UHR) from ten cancer cell lines (Sample A) and a cell line from a normal individual (Sample B). Mixtures of A and B in different ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:4, 4:1) are also created to mimic heterogeneity [43].

- Library Preparation:

- Targeted Sequencing: DNA or RNA libraries are prepared using various targeted panels (e.g., from Agilent, Roche, Illumina) based on hybridization capture principles [43].

- Whole Genome/Transcriptome Sequencing: Libraries are prepared using standard WGS or whole transcriptome (WTS) protocols, including both poly(A) selection and rRNA depletion for RNA [43].

- Sequencing Execution: Libraries are sequenced on multiple short-read (e.g., Illumina) and long-read (e.g., PacBio, Oxford Nanopore) platforms to assess cross-platform performance [43].

- Data Analysis Metrics: The analysis focuses on key performance metrics, including:

- On-target rate: The percentage of sequencing data aligning to the target region.

- Coverage uniformity: The evenness of sequencing depth across target regions.

- Variant calling accuracy: Sensitivity and specificity for calling SNVs, indels, and structural variants.

- Detection of splicing and fusion events: Particularly for RNA sequencing [43].

Market Trends and Adoption Drivers

The market for whole genome and exome sequencing is experiencing exponential growth, projected to grow from $2.02 billion in 2024 to $2.53 billion in 2025, at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 24.8% [6]. This growth is fueled by several key factors:

- Falling Sequencing Costs: Rapid cost compression is making broader panels and even WGS economically feasible in clinical settings. For example, Ultima Genomics reached sub-$100 whole-genome costs in 2024, and Illumina's NovaSeq X lowered per-sample expense by 60% [48].

- Rising Demand in Oncology: Therapy guidelines increasingly require concurrent analysis of multiple genes, prompting labs to replace single-gene tests with large pan-cancer panels. The FDA's classification of NGS tumor-profiling assays as Class II devices in 2024 has further clarified the regulatory path and accelerated adoption [48].

- Expansion in Rare Diseases: While oncology dominates, rare-disease diagnostics is the fastest-growing application segment (24.78% CAGR), driven by newborn genomic-screening pilots and expanded orphan-drug pipelines [48].

- Growth in Non-Invasive Prenatal Testing (NIPT): WGS-based NIPT is gaining traction due to its lower failure rates and simpler, PCR-free workflow compared to targeted approaches like SNP analysis or microarrays [46].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The reliability of sequencing experiments depends on the quality of reagents and materials used throughout the workflow.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Sequencing

| Reagent/Material | Critical Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Hybridization Capture Probes | Enrich specific genomic regions (e.g., exome or gene panel) from a fragmented DNA library prior to sequencing [2]. | Performance is evaluated by on-target rate, sensitivity, uniformity, and duplication rate [2]. |

| CRISPR-Cas Enrichment | A novel method using guide RNA and Cas enzyme to cleave and enrich specific target regions, offering high specificity and faster design cycles [48]. | Gaining share for its superior performance in GC-rich loci and for structural variant detection with long-read sequencing [48]. |

| Inhibitor-Tolerant Master Mixes | Enzyme mixes resistant to inhibitors found in blood or FFPE (Formalin-Fixed Paraffin-Embedded) samples, enabling direct genotyping without extensive DNA purification [49]. | Crucial for robust clinical sequencing from complex sample types [49]. |

| Library Preparation Kits | Convert extracted DNA or RNA into a format compatible with the sequencing platform through fragmentation, adapter ligation, and amplification [6]. | Kits are often optimized for specific workflows (WGS, WES, or targeted panels) and sample types (e.g., FFPE RNA) [43] [6]. |

| NGS Library Controls | Exogenous spike-in controls (e.g., Virus-Like Particle, VLP) added to the sample to monitor and validate each stage of the assay from extraction to final result [49]. | Essential for comprehensive performance validation and quality assurance in molecular diagnostics [49]. |

The advent of next-generation sequencing (NGS) has revolutionized clinical diagnostics, offering unprecedented capabilities for detecting genetic variations associated with human diseases. Within this landscape, two principal approaches have emerged: whole-genome sequencing (WGS), which aims to determine the order of all nucleotides in an entire genome, and targeted sequencing, which focuses on a select number of specific genes or coding regions known to harbor mutations contributing to disease pathogenesis [1]. While WGS provides a comprehensive view across the entire genome, including non-coding regions, targeted sequencing panels enable deeper sequencing of clinically relevant regions at a lower cost, making them particularly advantageous for clinical applications where specific gene sets are well-characterized [1] [46].

Targeted panels have gained significant traction in clinical settings due to their ability to provide high-depth sequencing for lower cost while delivering greater confidence in low-frequency alterations compared to broader sequencing approaches [1]. These panels typically include clinically actionable genes of interest for diagnostic and theranostic purposes, offering a practical balance between information content, cost-effectiveness, and analytical performance [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison of targeted sequencing panels against alternative genomic approaches, focusing on their performance in oncology, inherited disorders, and infectious disease applications.

Technical Comparison of Sequencing Approaches

Key Methodological Differences

The fundamental distinction between sequencing approaches lies in their scope and enrichment strategies. Whole-genome sequencing employs either de novo assembly, where sequence reads are compared to each other and overlapped to build longer contiguous sequences, or reference-based assembly, which involves mapping each read to a reference genome sequence [50]. In contrast, targeted sequencing panels utilize enrichment techniques such as amplicon-based approaches, which use polymerase chain reaction (PCR) with multiple overlapping amplicons in a single tube to amplify regions of interest, or hybrid capture methods that use oligo probes to capture specific genomic regions [51] [17].

Whole-exome sequencing (WES) represents an intermediate approach, targeting only the exonic regions that compose approximately 2% of the whole genome [1]. Each method offers distinct advantages: WGS provides the most comprehensive collection of an individual's genetic variation; WES enables deeper sequencing of coding regions at lower cost than WGS; and targeted panels achieve the greatest sequencing depth for specific genomic regions, making them ideal for detecting low-frequency variants in clinical settings [1].

Performance Metrics and Experimental Considerations

When evaluating sequencing methodologies, several quality control parameters are essential for assessing data quality. Sequencing depth refers to the ratio of the total number of bases obtained by sequencing to the size of the genome, significantly impacting the completeness and accuracy of variant calling [52]. Coverage represents the proportion of sequenced regions relative to the entire target genome, specifically the ratio of regions detected at least once compared to the total genome [52]. The mapping rate measures the proportion of bases in sequencing data that align to a reference genome, indicating data quality and consistency with the reference [52].